In the wake of World War II, decolonization and the Cold War reshaped urbanization processes around the planet.1 The untangling of Western European empires opened newly independent countries to resources and expertise beyond the West. Many leaders in Africa and Asia exploited the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union by turning to socialist states for assistance in diverse projects of economic modernization, social development, and state-building.

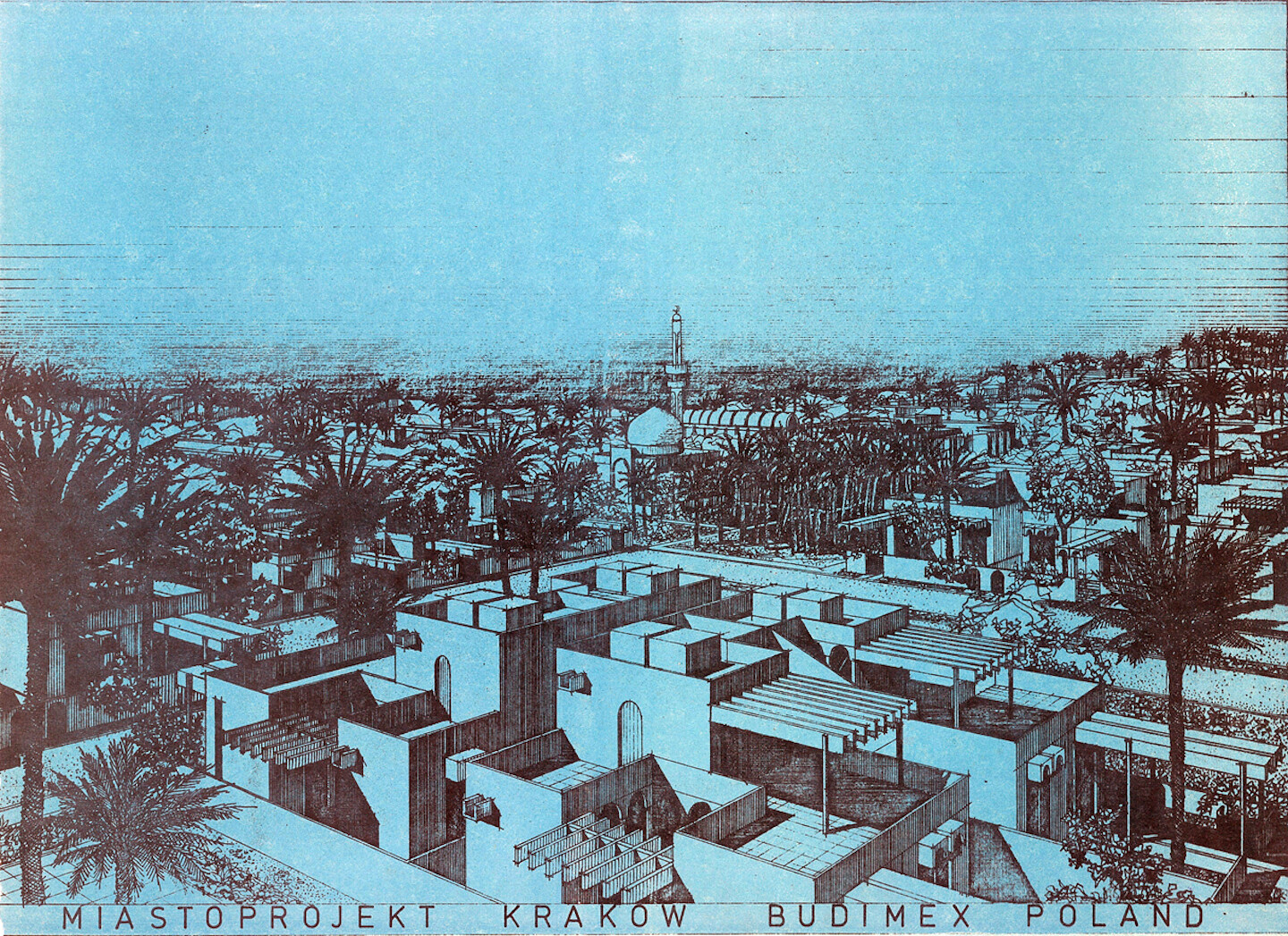

Housing was often central to the agreements which governments of newly independent states signed with socialist countries, including the Soviet Union, its Eastern European satellites such as Bulgaria, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Romania, as well as countries that pursued socialisms distinct from the Soviet model, among them Yugoslavia and China. This architectural mobilization resulted in new residential areas built in Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Chile, Cuba, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, India, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Mongolia, Nigeria, Sudan, Syria, Tanzania, Vietnam, Zambia, and elsewhere. Designed and constructed in collaboration with local partners, these projects made use of a variety of resources from socialist countries, among them the work of architects, design institutes and contractors, as well as building materials and machines, construction material industries including factories of concrete panels, type designs of residential buildings, urban standards of social facilities, master plans of cities and regions, nation-wide housing policies, educational curricula, and research projects focused on vernacular structures and their evolving ways of use.

Scholars in the Global North have largely ignored these processes and tend to explain urbanization on a world-wide scale as a result of the colonial encounter between Western Europe and the globalization of capital.2 I propose, however, an alternative history of housing after World War II, one centered on “global socialism,” or various and sometimes contradictory visions of cooperation, solidarity, and development practiced by the “Second” and “Third” worlds.3 Such a history requires one to pay less attention to battles of representations between ideological systems—how housing across Cold War divides has been predominantly described by architectural historians—and more to the political economy of architectural mobility from socialist countries.

In spite of its evolution throughout the course of the Cold War, this political economy was consistently defined by an ambiguous relationship between gift-giving and commercial exchange. This ambiguity was conveyed by a set of financial instruments used by socialist countries, including credits granted on favorable terms and the principle of barter. Credits, barter agreements, and other financial instruments impacted not only the global trajectories of state-socialist architecture, but also its modes of production, its materialities, technologies, and programs. The political economy of foreign trade in state socialism also shaped the conditions of labor of architects, planners, engineers, managers, and workers from Eastern Europe dispatched to the Global South, and the conditions for their collaboration with African and Asian decision makers and professionals. The resulting buildings, infrastructures, industrial plants, and regulations often continue to define urbanization processes across the Global South today.

Socialist Development

Since the late 1940s, the Soviet Union under Stalin offered technical assistance to China, Mongolia, and North Korea, and recruited its satellite states, including East Germany and Poland, for this task. This resulted in the design and construction of housing neighborhoods in Central and East Asia that often conveyed an interpretation of “national traditions” of their inhabitants—a concept that continued to inform Soviet architecture beyond its Stalinist guise. However, it was only under Khrushchev and the new policy of coexistence with the West—at the same time “peaceful” and “competitive”—that the Soviet Union and other Eastern European states expanded these exports to newly independent and decolonizing countries in Africa and Asia in a way that challenged the former colonial powers in Western Europe and the United States.4

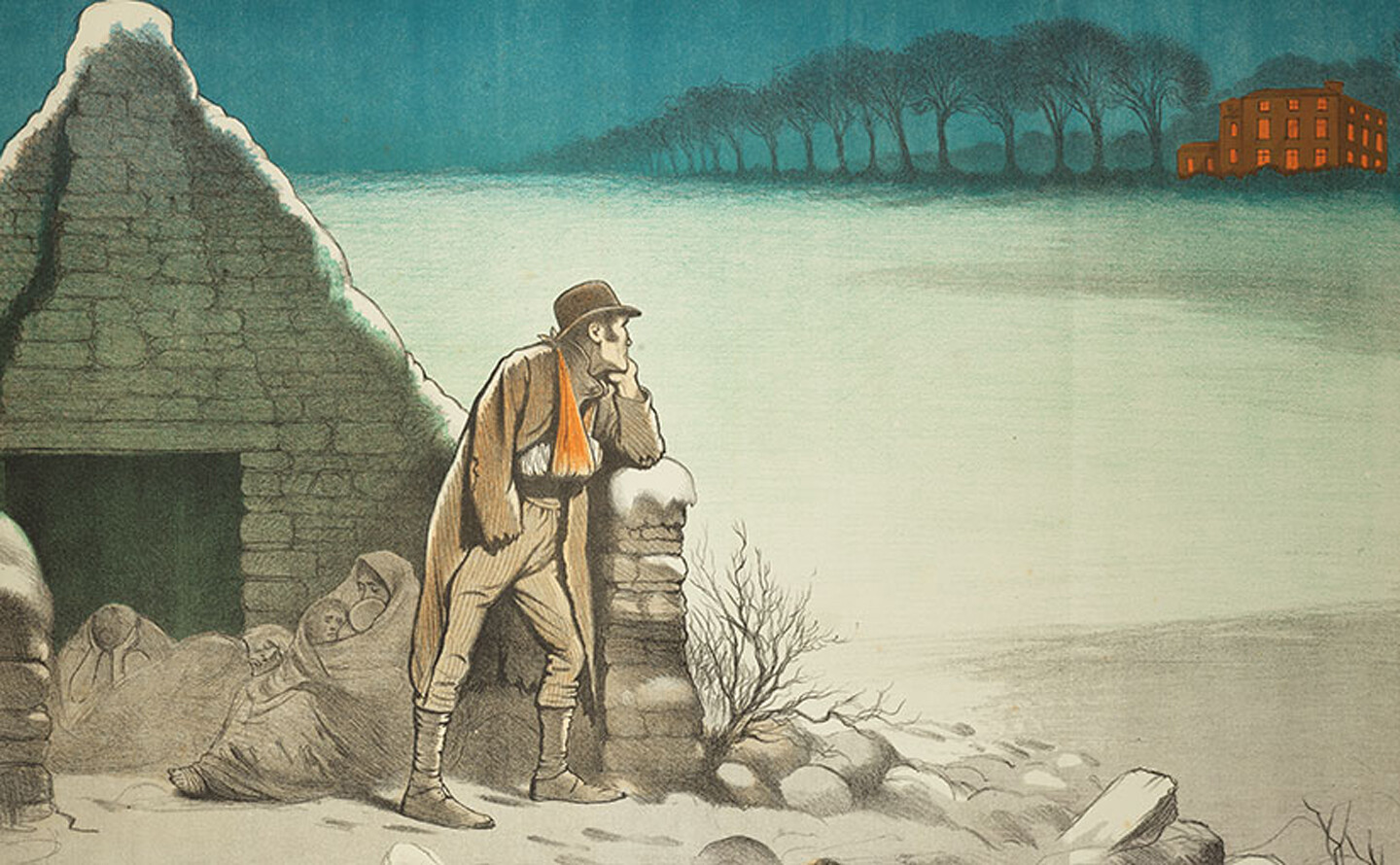

The stress on housing in these exchanges reflected the priorities of many governments in the Global South. The contrast between colonial bungalows in tropical gardens and the rundown informal settlements of indigenous populations was a familiar sight in colonial cities in Africa and Asia, and many first-generation postcolonial leaders saw its undoing as a fundamental promise and obligation of independence. More pragmatically, housing was needed for the growing state administration, army, and police, on whose loyalty the new regimes depended. The construction of housing was often part of a broader effort to develop construction and construction material industries, and of industrial modernization at large. Most leaders and decision makers considered fast-track industrialization to be indispensable for political and economic independence from the former colonial metropoles and for the generation of income that would fund egalitarian programs of welfare distribution.

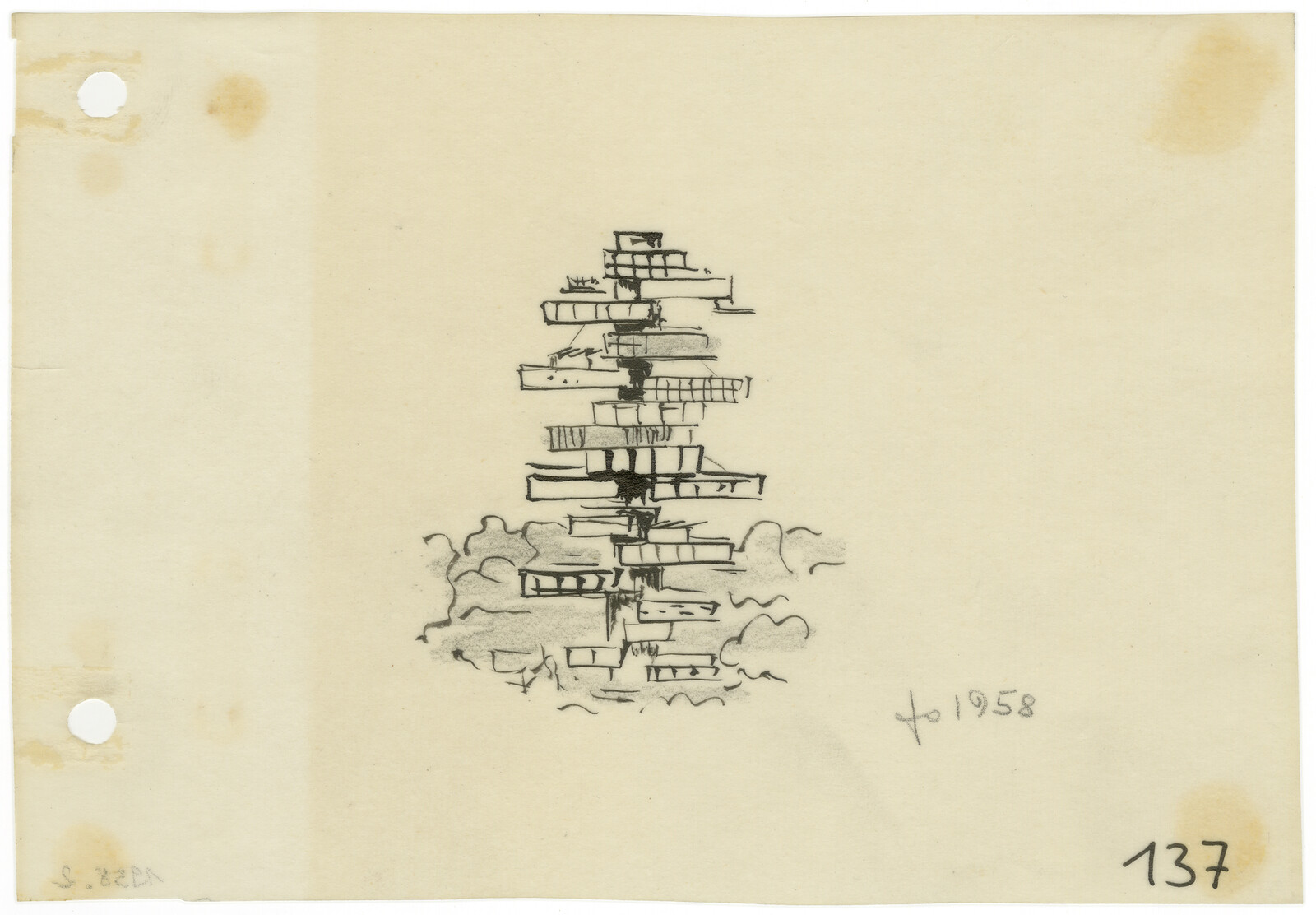

The Soviets posited their housing industry as a model for a radical shift beyond the colonial period, and after the Sino-Soviet split in the early 1960s, they further contrasted this model with the emerging Chinese aid initiatives that assumed incremental change. Based on state ownership of land and means of production, the Soviet housing industry was reorganized under Khrushchev towards the supply of compact, economical apartments to Soviet citizens located within micro-districts (mikroraiony) furnished with a nested system of social facilities. These structures were built by means of large prefabricated panels produced by “housebuilding factories,” of which more than 200 were constructed by the early 1960s on Soviet territory. By that time, the Soviets announced that during the preceding five years, they rehoused fifty million people into modern apartments.5 Built in urban and rural areas, these apartments were adapted to various climates of Soviet republics, from the permanently frozen soil of subarctic regions to hot-dry Central Asia.

These experiences were prominently displayed in Khrushchev’s propaganda campaigns in the decolonizing states in Africa and Asia, and supported Soviet claims to a global expertise in housing construction. Soviet transfers of this expertise were informed by three principles.6 First, housing production was to be integrated into the “material-technical base of construction,” meaning an interlinked system of construction and construction materials industries, state construction enterprises, central planning institutions, research centers, and universities. Accordingly, technical assistance agreements signed under Khrushchev in Afghanistan, Mongolia, Ghana, and Cuba centered on the design and construction of factories of large concrete panels as central nodes of such integrated construction industry.

Second, Soviet typologies and technologies were to be dynamically adapted to local conditions, in particular climatic and geological, but also to customs and the evolving patterns of “national” culture and everyday life. Housing industry in Soviet Central Asian republics was showcased as a paradigmatic precedent for such adaptation. Delegations from Africa, Asia, and Latin America visited housing neighborhoods in Tashkent (Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic), and studied how they accommodated not only the climatic and seismic parameters of the region, but also customs and “national traditions” of Uzbeks “liberated” by the Soviet Union from the “colonial” tsarist oppression.7 Beyond Central Asia, Soviet architects and engineers adapted technical details of prefabricated systems, apartment plans, and neighborhood layouts to the tropical climate in the Caribbean and in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as the cold winters in Central Asia. These modifications also accounted for local technologies and ways of life. For example, Soviet housing in 1950s Mongolia allowed for the use of solid fuel cast-iron stoves before the introduction of centralized heating, and later layouts provided for a balcony which was used to freeze meat supplies during the winter. Design modifications such as these were often introduced on the explicit request of local administrators and architects.

In contrast to the Western view of African and Asian governments as Soviet “proxies” or “pawns,” collaboration with local cadres was the third principle of Soviet architectural mobilities. The Soviets insisted on collaboration both in order to distinguish themselves from Western European colonialists and to secure resources and commitment from their local counterparts. After decades of Soviet technical assistance in Mongolia, for instance, residential areas in Ulaanbaatar read not only as a display of increasingly sophisticated Soviet prefabricated systems—ones that allowed for rising heights, flexibility, and variability—but also testify to the increasing takeover of Mongolian architects of every stage of the design and construction process.

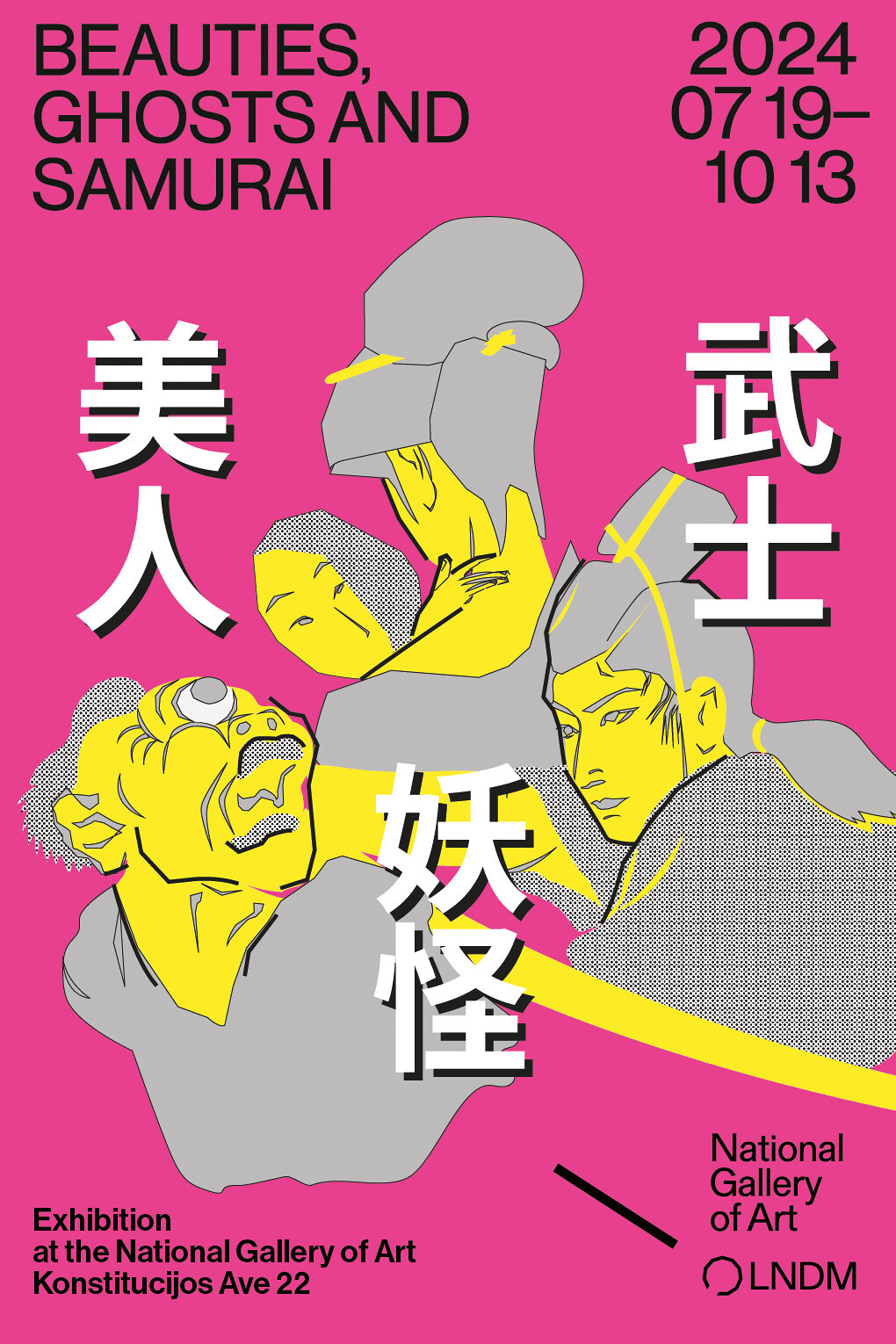

“People’s Art Club of Residential Area, Accra,” 1962. Giprogor (USSR). Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv ekonomiki (Samarra, Russian Federation). First published in: Stanek, Architecture in Global Socialism.

Gift, Credit, Barter

The Global Cold War was fought on many fronts, and statistics was one of them. A case in point were articles published in the Ghanaian newspaper Daily Graphic in 1965, one of which claimed that “the Soviet Union has surpassed the United States of America, for instance, not only for the total number of apartments it builds, but for per capital dwelling construction, as well.”8 This statistic was relevant at a time when Ghana, under the socialist government of Kwame Nkrumah, embarked on major projects of housing construction supported by architects and engineers from Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Union.

Among the most consequential numbers for Ghanaian decision makers was 2.5%: the interest rate of credit that the Soviet Union typically offered to the newly independent countries in the Global South. Until the end of the Cold War, Soviet politicians and economists saw cheap, long-term credit as a distinct feature of Soviet foreign trade with developing countries.9 This interest rate was lower than the rate of return on investment in the Soviet Union and below the rates offered by Western financial institutions. For example, at the time when the Soviets granted Ghana a loan with a 2.5% interest rate, London-based banks offered Ghana commercial credits at a 6% interest rate.10 In this sense, these credits echoed the dynamics of gift-giving—the most visible manifestation of Khrushchev’s diplomatic offensive in the Global South. Symbolizing the difference between socialist and capitalist systems, buildings-as-gifts—such as the students’ dormitory in Bamako donated by the Soviets to the Malian government in the early 1960s—suggest a temporary negation of architecture’s commodity form and a reciprocity stronger than a mercantile relationship.11

Soviet technical assistance agreements, including those signed since 1960 with Ghana, were ambiguously situated between commercial exchange and gift economy. The agreements with Ghana foresaw the delivery of a Soviet large panel factory of housing elements to Accra. In addition, Soviet architects designed two mikroraiony, which were to be constructed by Ghanaian state contractors on the basis of the room-size panels produced by the factory. The work of Soviet designers and advisors in the project was paid by Soviet credit, while Soviet machinery and building materials (such as cement and iron rods) were exchanged for Ghanaian agricultural goods (in particular cocoa beans, Ghana’s main export commodity).

By the 1960s, such barter agreements became the dominant form of economic exchange between African and Asian countries and the Soviet Union, East Germany, Bulgaria, Poland, and other socialist states in Eastern Europe. They expanded the barter economy towards the “Third World” that had been practiced among member-states of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (or Comecon, the Soviet-dominated economic organization of socialist countries) since the end of World War II. Barter arrangements aimed at supporting local industries in newly independent countries with goods and services needed for industrial and social development, while redirecting economic exchange away from former colonial metropoles. They were attractive for both socialist and developing countries, most of which were in short supply of (Western) exchangeable currencies. Furthermore, long-term contracts for agricultural goods, often priced above their value in international markets, allowed agricultural producers to avoid price fluctuations on these markets.

Besides economic advantages, the agreement with the Soviets was instrumental for Nkrumah’s program to reconstruct the Ghanaian society. The apartment blocks were to set a precedent of an egalitarian welfare distribution. Redrawn according to instructions of Ghanaian architects, the layouts accommodated West African customs, such as the possibility of outdoor cooking, but without essentializing particular ethnic groups in Ghana, as had been common during the colonial era. The program of the housing neighborhoods conveyed a vision of a socialist everyday life. Facilities such as People’s Art Club were to provide a venue for collective education and leisure, while nurseries, kindergartens, laundries, and canteens were to alleviate domestic work of women, thus advancing their professional prospects.12 At the same time, the creation of the prefabricated panel factory was part of an envisaged reorganization of the Ghanaian construction and construction material industries within a centralized, state-led planning framework. In this sense, the neighborhoods were catalysts, meant to trigger a fundamental transformation of the Ghanaian economy towards the Soviet model. That, too, pointed at the dynamics of gift-giving which was described by anthropologists as a “total social fact,” at the same time juridical, economic, religious, and aesthetic.13

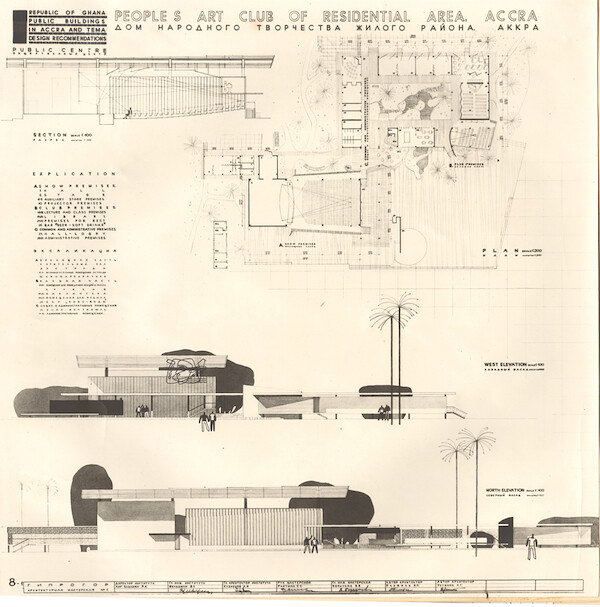

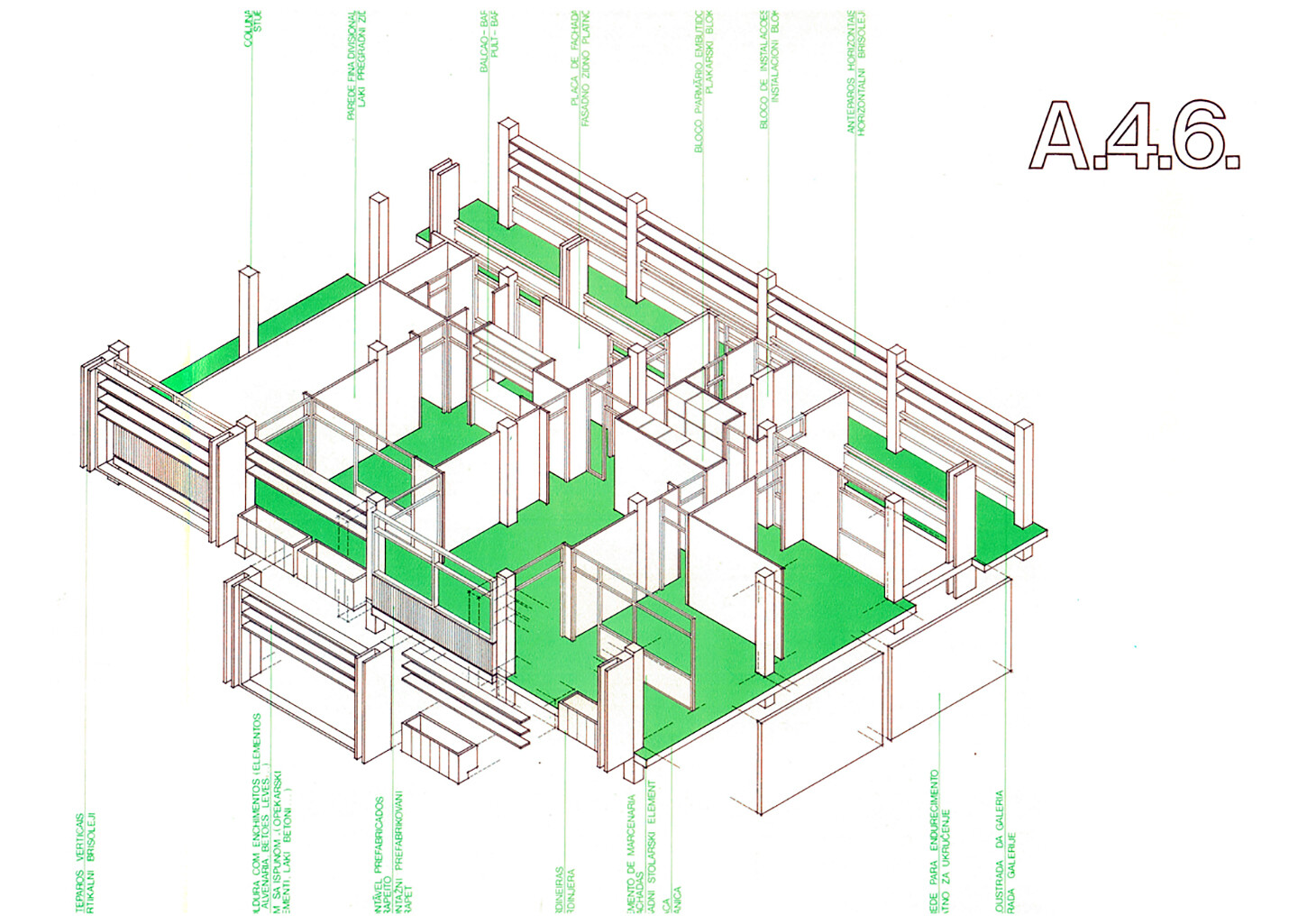

Housing project for Libya, 1980s. Romproiect (Romania), Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Bucharest.

Architecture and Petrobarter

After the prefabricated panel factory was completed in Accra, a coup that toppled Nkrumah in 1966 interrupted the construction of the mikroraiony. This event pointed to the risks of Khrushchev’s policy in the “Third” world which, in spite of significant investments, rarely led to sustained political influence or economic benefits for Moscow. Under the Brezhnev administration, the Soviets and their Eastern European satellites continued to support housing industries in less developed Comecon member states, including Mongolia, Vietnam, and Cuba, and only occasionally engaged in gift diplomacy, as with the large panel factory gifted to Chile under the short-lived presidency of Salvador Allende.14 Yet in spite of the general reorientation of Soviet technical assistance towards more tangible benefits for the USSR, such as access to raw materials, the political economy of architectural mobilities from socialist countries continued to be ambiguously situated between gift-giving and commercial exchange.

This ambiguity was perpetuated by means of barter contracts between Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, which accelerated in the wake of the oil embargo of 1973. The profits from oil sales, deposited by Arab governments in Western banks, were lent to socialist countries in need of modernizing their industries and financing their models of consumer societies. Yet when their industrial leap failed to materialize, socialist countries, including East Germany, Poland, Bulgaria, and Romania, found themselves struggling with huge debts in foreign currencies.15 As a result, they expanded their trade with oil producing countries such as Iraq, Libya, and Algeria, which included the exchange of design and construction of housing for crude oil. Oil obtained in the course of such “petrobarter” agreements was used to satisfy the rapidly increasing demand by the energy-hungry economies in socialist countries. It was also sold to the West to provide supplementary income for debt repayment.

The work of Romanian design institutes and construction companies testifies to the impact of petrobarter on materiality, technology, design, and programs of residential areas throughout the Middle East and North Africa. On direct instruction of Romania’s dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu, these companies expanded their export activities in North Africa and the Middle East. Crude oil was exchanged for long series of buildings, including housing neighborhoods constructed by Romanian workers who drew upon technologies, machinery, and construction materials shipped from Romania or produced on site. Romanian companies offered housing layouts differentiated by the climatic conditions of specific countries, local standards, technologies, customs, and budgets. Based on type designs such as those included to the catalogue Housing buildings for export (1984), these buildings were often delivered with fitted kitchens and bathrooms, and sometimes fully furnished, including TV sets, stoves, and sinks.16 Such comprehensive planning extended from individual buildings to whole neighborhoods, with Romanian catalogues including plans of hotels, supermarkets, restaurants, kindergartens, schools, and sports facilities. When the local commissioners required Romanian companies to construct housing according to third-party blueprints, Romanian architects redrew them so that they could be constructed by means of machinery, material, equipment, finishing, and labor from Romania.

The consequences of this approach can be seen in industrial towns and rural settlements in Iraq, as well as type housing projects offered for Baghdad, Mosul, Basrah, and other cities in the country. Among the biggest commissions constructed by Romanian companies around the Mediterranean was the housing estate at the Airport Road in Tripoli (Libya), as well as three housing neighborhoods in Saida (Algeria). Completed by 1987, the latter were constructed together with green spaces and roads; water, sewage, telephone, electricity, and gas infrastructure; as well as streets and parking spaces (with street lights), playgrounds, and sport facilities.17 The Romanian companies involved exploited the petrobarter system and, more generally, the difference between the political economy of state socialism and the emerging global market of design and construction services dominated by Western Europe and North America. But these commissions also evidenced the fact that this “exploitation” included exploiting the country’s own population. In contrast to architects from other socialist countries who were eager to work abroad motivated by financial benefits, professional ambition, and an opportunity to travel, when interviewed today, Romanian architects often recall that they resisted going to the North African construction sites, where they were housed for months in camps far away from cities with little else to do than work.

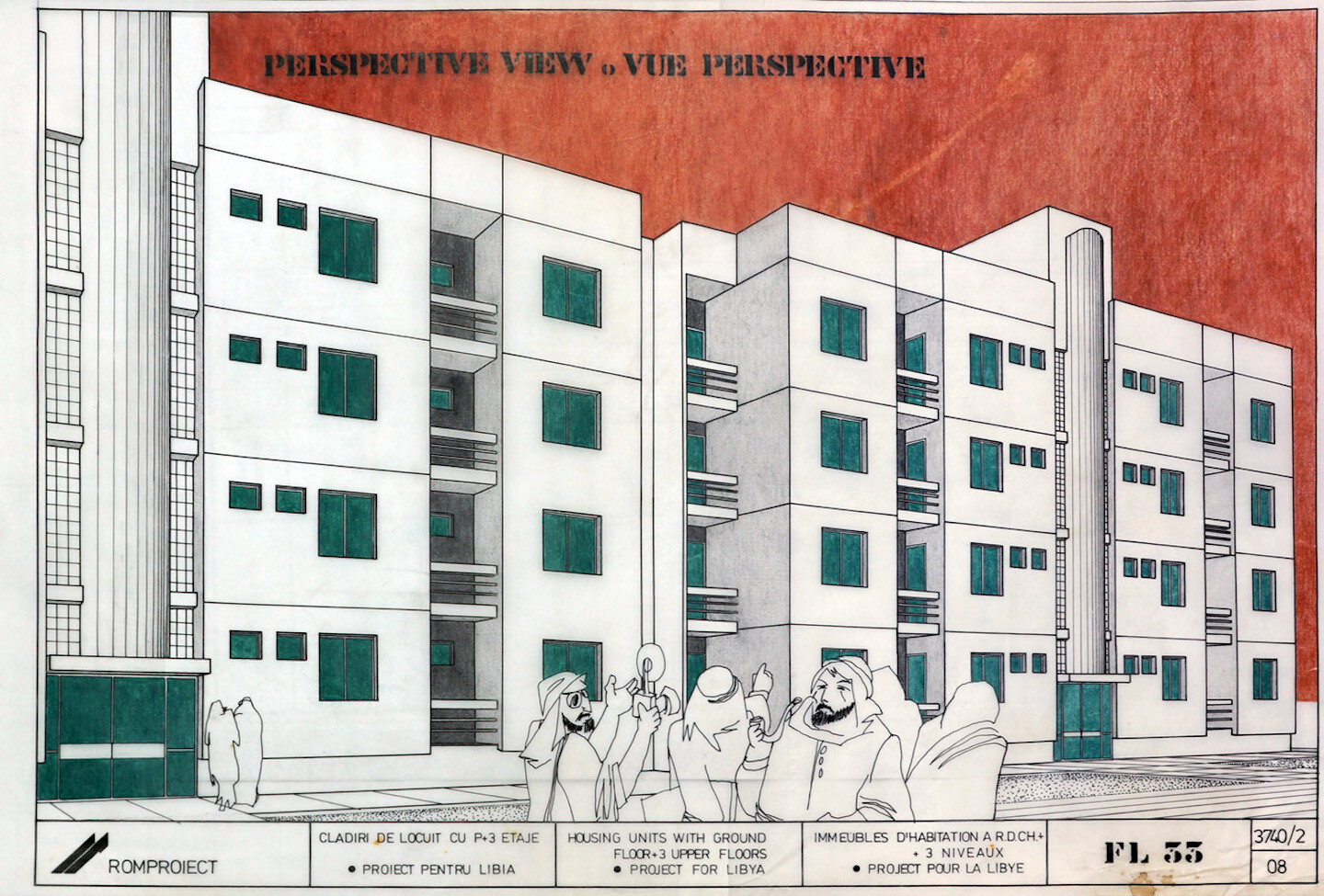

Housing project delivered in the framework of the General Housing Programme for Iraq, 1976-80. Miastoprojekt-Kraków. Private archive, Kraków (Poland).

Weak Actors

The mapping of housing projects delivered within the petrobarter system by state-socialist design institutes and contractors reveals a geography that transgressed the dichotomies of the Cold War. Some of their major destinations, including Iraq under the Baath Party, Syria under Hafez al-Assad, Libya under Gaddafi, and Algeria under Boumédienne, were nominally socialist countries or countries governed by socialist parties. But they guarded their political, economic, and military independence from the Soviets, and sometimes preferred working with smaller Eastern European socialist states. Enterprises and individuals from Soviet satellites were also invited by African and Asian governments without any socialist sympathies, including Nigeria and the monarchies of the Middle East, notably Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. Rather than pursuing a socialist development path, these governments commissioned Eastern European architects and companies in order to offset the dominance of Western firms, to encourage competition between foreign enterprises on their markets, to fast-track the development of their construction industries, and to alleviate the shortage of qualified workforce.

Henryk Roller and his Syrian collaborators at the Urban Planning Office of the Municipality of Aleppo, Syria. Roller was employed at the Office from 1969 to 1977. Private archive, Warsaw.

With this shift in geographies and motivations, the parameters of housing commissions shifted too. The trajectory of Hungarian architect Charles Polónyi is instructive in this respect. Polónyi’s first foreign deployment was in Ghana under Kwame Nkrumah. Yet in contrast to the Soviet designers of the mikroraiony in Ghana, who were sending blueprints from Moscow, Polónyi was among a large group of Bulgarian, Polish, and Yugoslav architects who were employed by Ghanaian design institutes, contractors, ministries, and universities. During his stay in the country he designed a range of housing projects, from individual bungalows for the new elite to a housing estate in central Accra, as well as rural resettlement projects. During his next deployment in the region, in Nigeria, he advanced this work. In the city of Calabar, for instance, his team planned a settlement system differentiated according to a dynamic continuum of conditions ranging from rural to urban. In this plan, housing was designed not just as a means of welfare provision, but also as a stimulus for the construction industry, and an opportunity for training and employment.

Flagstaff House housing project, Accra, 1964. Ghana National Construction Corporation, Vic Adegbite (chief architect), Charles Polónyi (project architect). Photo by Ł. Stanek, 2012. First published in: Stanek, Architecture in Global Socialism.

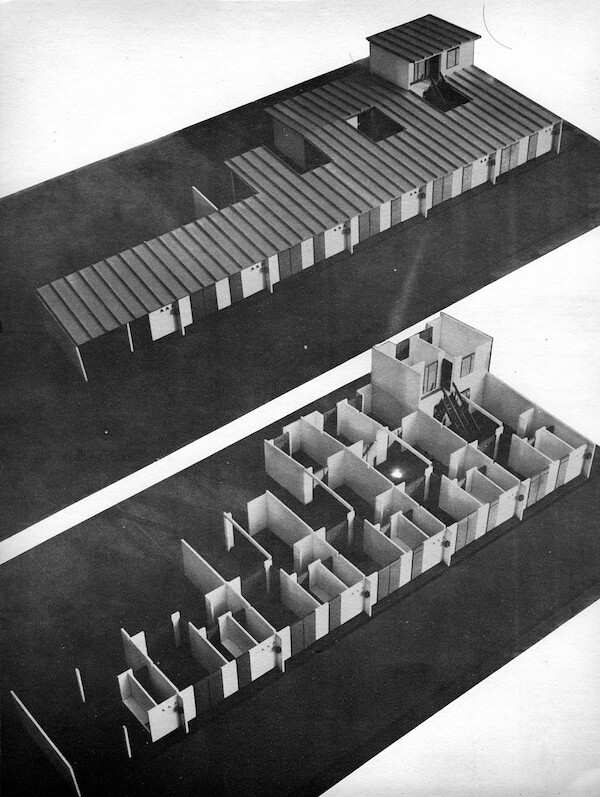

This design approach reflected Polónyi’s earlier experience in rural Hungary, and debates on rural underdevelopment on the territories of the Habsburg monarchy before World War I.18 Longer traditions of rural planning in Eastern Europe, and architectural culture of the region more generally, provided a pool of references and precedents that architects from socialist countries tapped into during their work in the Global South. For example, Yugoslav and Romanian architects and planners in Nigeria drew on their earlier experiences of “transitory housing” that socialized rural populations to urban conditions. In turn, the nation-wide General Housing Programme for Iraq, delivered by Polish and Iraqi architects in the late 1970s, drew upon surveys of vernacular architecture in various Iraqi regions and included designs of model villages.19 In difference to industrial prefabrication promoted by the Soviets, the Polish-Iraqi team foresaw light, small-scale prefabrication systems which did not require the use of heavy machinery.

Calabar, model of low-rise high-density housing, 1969. Design Institute for Public Buildings (KÖZTI, Hungary). “Survey and Development Plan for Calabar” (Calabar: Tesco-Közti Consulting Engineers (NIG.) Ltd., 1969), 2.13. Private archive, Budapest.

The equalization of the living conditions between the cities and the countryside was a constant theme in socialist propaganda both in the “Second” and the “Third” worlds. But for Polónyi and others, the question of rural development pointed to broader commonalities between these two worlds that stemmed from the long nineteenth century. These commonalities included the occupation of Eastern Europe by Prussia, Austria, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire; economic exploitation by the capitalist core; and cultural devalorization by Western Europe. Speculations about such commonalities inspired architects from socialist countries to revisit their planning tools, representational instruments, and design concepts that had been introduced in Eastern Europe in response to historical challenges that Eastern Europeans presumably shared with the colonized people of Africa and Asia.

The portability of these experiences was limited, notably due to the ambiguities of Eastern Europe’s own colonial history. The Polish architect and scholar Zbigniew Dmochowski, for instance, studied vernacular building cultures in Nigeria by means of survey techniques from prewar Poland in order to open the way towards a “modern school of Nigerian architecture.”20 While this work referred to turn-of-the-century debates about the role of the “national house” in state-building after the “colonization” of Eastern Europe by foreign empires, it also confronted Dmochowski with the ambiguity of Poland’s colonial experience. The latter included not only the Nazi genocide that aimed at clearing Eastern Europe for German colonists, but also Poland’s own “internal colonization” of the country’s eastern territories during the interwar period.

Lessons from the Eastern European village and debates about the “national house” helped architects from socialist countries substantiate the relevance, value, and applicability of their expertise for the post-independence Global South. This was necessary, given the skepticism of local elites, who were often educated in colonial metropolises, and their sympathy for the devaluation of Eastern European expertise by Western Cold War propaganda.21 Yet the weak bargaining position of Eastern Europeans stemmed not only from ideological vagaries, but also from the political economy of state-socialist foreign trade. This weakness was shared by state-socialist companies under pressure to fulfill the compulsory “convertible currency plan,” as well as by individual architects employed by a local planning institution for whom a dismissal would inhibit career prospects and deprive them of the opportunities that went with contracts abroad. Weak bargaining power, and the flexibility and adaptability of non-Soviet state-socialist actors that often went with it, made them highly instrumental within development roadmaps of local administrators, planners, and decision makers. As a result, their impact on urbanization processes in a range of different places in the Global South was often far greater than that of powerful centers, including the Soviet Union.

Sabah al-Salem Neighborhood Site C (Kuwait), 1977-82. Shiber Consult and INCO, Andrzej Bohdanowicz, Wojciech Jarząbek, Krzysztof Wiśniowski (design architects). Photo by Ł. Stanek, 2014. First published in: Stanek, Architecture in Global Socialism.

Global Entanglement

By the end of the Cold War, the commissions of state-socialist contractors, design institutes, and individual architects from Eastern Europe spanned from low-income housing estates in Kuwait and Iraq delivered by Polish architects to luxurious villas in Abu Dhabi and Dubai designed in Bucharest and Belgrade, East German type designs for Yemen and Mozambique, Yugoslav proposals of prefabricated housing systems for Angola, Romanian housing estates in Libyan desert cities, Bulgarian tourist development in Tunisia, and Hungarian neighborhoods in Algeria. This production was intimately intertwined with urbanization processes in Eastern Europe, including undifferentiated housing estates built by construction companies stretched thin by their export obligations, and new neighborhoods of detached houses which, by the 1970s, were emerging on the suburbs of Warsaw, Prague, Budapest, Belgrade, Sofia, and elsewhere to house party officials and doctors, as well as architects, engineers, and managers returning from “export contracts.” These neighborhoods testify as much to the hard currency brought from abroad as they do to other flows, including new technologies, aspirations, and patterns of everyday life. The entanglement of these seemingly disparate urbanization processes in Eastern Europe and the Global South, therefore, cannot be reduced to the narrative of “Westernization” or “Americanization,” which became dominant after the end of the Cold War and the capitalist triumphalism that followed.

Housing for Angola, 1979. Centre for Housing IMS, Belgrade (Yugoslavia). “Urbanização Lixeira. Catãlogo dos apartamentos” (Belgrade: Centre for Housing IMS, 1979).

The consequences of these historical exchanges continue to condition urbanization processes in many places of the Global South today. Besides ongoing collaboration between individuals and companies from Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe, a large number of the housing neighborhoods and social facilities continue to be inhabited. Some of them have been renovated and expanded, while others suffer from neglect and disinvestment. The legacies of global socialism’s architectural mobilities also include master plans and building legislation which regulate the planning of housing neighborhoods, from plot sizes and density ratios to catchment areas and radii of social infrastructure. Particularly relevant are construction material industries, such as Soviet large-scale panel factories. Some, among them the factory in Accra, were refurbished and adapted to the production of smaller-scale concrete elements, while others are being given a new life. The housing factory in Ulaanbaatar, for instance, which was originally constructed by the Soviet Union in the early 1960s, was recently equipped after more than twenty-five years of inactivity with machinery from Belgian, German, and Italian manufacturers, and is on its way to launch a production of prefabricated panels with improved technical parameters. Building upon existing infrastructure and skills, but also addressing the hesitation of potential clients about a technology produced by the Soviet factory, its current staff reinterprets the legacy of global socialism on a daily basis.

This article is based on my research presented in the recently published book: Łukasz Stanek, Architecture in Global Socialism. Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020).

Aihwa Ong, “Worlding Cities, or the Art of Being Global,” in: Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global, eds. Ananya Roy and Aihwa Ong (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 1–26.

Stanek, Architecture in Global Socialism.

Odd Arne Westad, The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Report of the Study Tour of Building Technologists from Latin America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, 3 to 31 July 1963 (New York: United Nations, 1964), 16–17.

For discussion, see: Nikolay Erofeev and Łukasz Stanek, “Architectural Mobility in the Comecon: Integration, Adaptation, and Collaboration in Socialist Mongolia,” forthcoming.

Paul Stronski, Tashkent: Forging a Soviet City, 1930-1966 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010).

Daily Graphic (Accra), November 6, 1965, 11.

Leon Zalmanovich Zevin, Economic Cooperation of Socialist and Developing Countries: New Trends (Moscow: Nauka, 1976), 49–50.

Daily Graphic (Accra), March 5, 1962, 5.

Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv ekonomiki (Samarra, Russian Federation), f. R-621, op. 5-4, d. 646; Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov, “On Heterochrony: Birthday Gifts to Stalin, 1949,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 12, no. 2 (2006): 355–75.

Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv ekonomiki (Moscow, Russian Federation), f. R-150, op. 2-1, d. 414; f. R-850, op. 9-4, d. 38 and d. 43.

Marcel Mauss, The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies (London: HAU Books, 2016).

Andrés Brignardello Valdivia, KPD: historia social y memoria de una fábrica soviética en Chile (Valparaíso: América en Movimiento Editorial, 2016).

Stephen Kotkin, “The Kiss of Debt. The East Bloc Goes Borrowing,” in: The Shock of the Global: The 1970s in Perspective, eds. Niall Ferguson et al. (Cambridge, London: Belknap, 2010), 80–93.

Arhivele Naţionale ale României (Bucharest, Romania), f. Romproiect, 7099.

Arhivele Naţionale ale României (Bucharest, Romania), f. Romproiect, 7398.

Charles Polónyi, An Architect-Planner on the Peripheries: The Retrospective Diary of Charles K. Polónyi (Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó, 2000).

“General Housing Programme for Iraq,” 1976-80, 21 vols., Private archive (Kraków, Poland).

Zbigniew Dmochowski, An Introduction to Nigerian Traditional Architecture, Vol. 1 (London: Ethnographica; Lagos: National Commission for Museums and Monuments, 1990), ix.

Carl E. Pletsch, “The Three Worlds, or the Division of Social Scientific Labor, circa 1950-1975,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 23, no. 4 (1981): 565–90.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.