Rent control and anti-eviction measures in general have attracted enormous attention in recent years because they directly address the issue of displacement and eviction that are so important to the dynamics of poverty in our time.1 Almost no attention has been paid to the origins of rent control, however, which appeared for the first time in 1881, established by a little-studied institution, the Land Court of Ireland.

The story of rent control in its nineteenth-century context has broader implications than rent control as typically talked about—as a cure for the “livable city” or cities as “creative capitals.” In the nineteenth century, rent control was an anti-colonial measure. Rent control, as a theory, was possible only because the Victorian Liberal Party, under the direction of William Gladstone as prime minister, embraced the logic of historical reparations for the English colonization of Ireland, the illegal seizure of property, and the prohibition against Catholic persons owning property. In effect, rent control promised to reverse the racism of an economy established under empire.

Rent control would operate by ratcheting back Ireland’s famous “rack rents” into “fair rents” under the charge of ending an era of eviction and incendiary violence in the countryside. Its workings set the pattern for the Bengal Rent Act of 1885 and the associated Land Court of Bengal, and also offered the immediate example upon which David Lloyd George’s nation-wide Valuation Survey of England and Wales—the basis of a new property tax designed to keep land affordable to the poor—was begun in 1910, and from which urban rent control proceeded between 1939 and 1988.2

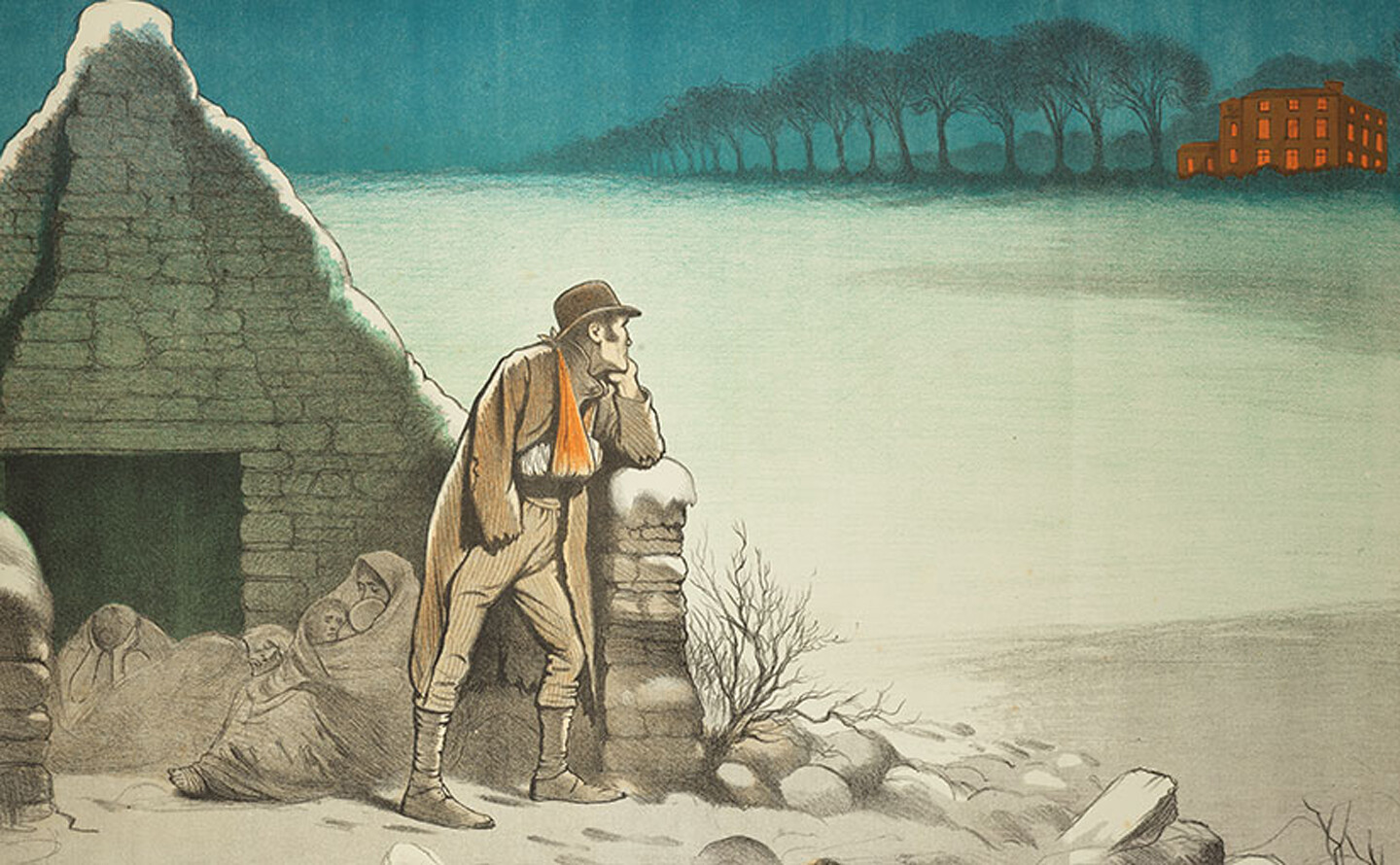

Thomas Considines stares down the police in front of his home in Tullycrine, July 1888. Source: National Library of Ireland.

Empire and Rent in Nineteenth-Century Britain

During the Irish Famine (1845–1849), a third of Ireland died, one third emigrated, and a third survived in squalor, preserved by meager rations of gruel dispersed by the British government, which was, in the 1840s, unwilling to embrace any policy that resembled a departure from the free market. In the decade after the famine, Irish activists began to debate the economy in detail. They proposed ideas about an economy that would give opportunity to all. At the core of those ideas were notions that defined rent and eviction as issues at the crux of how poor people fared in an economy.

Since at least the 1840s, Irish pamphleteers described the eviction of Irish tenants by absentee landlords and argued for the recognition of customary Irish law, which recognized tenancy as a form of ownership, such that a departing tenant “sold” the right to a tenancy to the incoming renter. In the critique of political economy associated with the Irish Tenant League and radical newspapers, Irish theorists proposed alternative modes of political economy that would limit rent hikes and credit tenants who make improvements to properties in the form of rent reductions.3 Some of these ideas continued to circulate through the 1850s and 1870s and were expanded in textbooks, essays, and pamphlets on tenant valuation, fair rent, and political economy.4

According to Irish theorists, high rents had the ironic impact of raising investor expectations of profit in such a way as to ratchet prices in one direction only: up. Evidence of high rents among starving peasants led absentee landlords, who rarely saw the conditions of Irish misery for themselves, to assume that high rents were afforded by technological progress and innovations in farming, and that potentially the rents could be raised forever. Together, the force of rising expectations on returns and tenant misery created a destructive cycle for the economy as a whole. Rather than a business cycle, Ireland had a speculation and eviction cycle.

After decades of theory, in 1879, Irish political leaders launched a simultaneous plan of parliamentary advocacy and grassroots marches, encouraging tenants to refuse to pay rent in districts where rent had escalated. Landlords retaliated, calling upon the police to evict tenants for non-payment. Tenants, in turn, responded by organizing massive sympathy rent strikes, where even those able to pay deliberately withheld rent in solidarity with other tenants.

This so-called “Land War” helped to make rent and eviction the focus of parliamentary debate from 1879 to 1886. It marked a moment of escalation on both sides: from theories of fair economies to deliberate, concentrated political action and coordinated economic resistance. Alongside concurrent political and intellectual developments in England—where intellectuals such as John Stuart Mill and Goldwin Smith were arguing for the historical relativity of single-proprietor property law—and the coordinated pressures of the Irish representatives in parliament, the Land War helped to destabilize faith in the ultimate benefits of a landlord-driven economy, opening parliamentary language towards a new discourse of the rights of occupation.

The aggregate result of these forces was a new attitude towards rent, in England and Scotland as well as Ireland. This attitude has long been understood as one dimension of the origin of socialist thinking, in which working-class people looked to the state to control the price of rent and ensure adequate housing, as well as access to parks and transportation for all. The shift is visible in how the parliamentary language of property changed over the course of the 1870s and 1880s, from terms based in market price such as “freehold” and “ground rent,” or the feudal language of the “copyhold,” towards a language where the concerns of the “tenant” and “crofter” were discussed openly alongside the issue of “rent” and “eviction.”

The shifting language of property. Keywords related to occupancy over time, searching within the top ten debates most relevant to each term. Note that the y-axis is logarithmic, meaning that the instance of terms higher on the chart represents an exponential increase over the number of mentions of the terms lower on the chart. Source: Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates of Great Britain, 1803–1911; searching for terms derived from the Oxford Historical Thesaurus.

Another aspect of a cultural shift in understandings of property was the introduction of new ideas about rent and land, manifested in the form of rent control and legislation to redistribute landholding for Ireland (where both forms of legislation were realized) as well as England and Scotland (where legislation was introduced but only limited rent controls enacted). From the 1880s through the 1970s, variations on rent control, land redistribution, and land nationalization schemes typified land-use policies in most developed and developing countries.

The pivot of this era, however, was the introduction of rent control in Ireland in 1881. In the context of short-term politics, rent control legislation was made possible by a combined program of parliamentary action and on-the ground resistance that dramatized the complaints of Irish tenant farmers, Irish rates of eviction, and the history of rent increases. Irish speakers in parliament described both popular resistance and the suppression of popular resistance as evidence of a cycle of violence bound up with unfair monopolization of land by a colonial power, which was impossible to eliminate by police force, suppression of the press, or bans on public gatherings. The only alternative to an endless “Land War” in Ireland, they argued, was to turn Irish land over to Irish tenants. The response that parliament finally approved was a joint measure of rent control with the option for tenants to purchase their land outright, as enshrined in the Land Act of 1881. It was a government institution wholly new to Britain, aimed at essentially limiting the economic damage that rent strikes could do by forcing landlords to acquiesce to a new set of prices determined not by the market but rather by the courts. That alternative institution was only possible because it had been theorized—and data supporting the theory had been collected—by Irish professionals and activists over generations.

The Economics of Fair Rent

Since early in the nineteenth century, English theorists of economics had asserted that the prices of rent, interest, and other commodities were essentially artificial: they fluctuated not with supply and demand, but according to which political interests directed parliament at any given time. David Ricardo’s theory suggested that when landlords had power, the price of land and grain rose and workers in factories suffered. When bankers or manufacturers had power, conversely, the price of land tended to fall. Prices, in other words, were artificially determined by who bid on them at a particular moment.

The market price of land itself—as Irish theorists of rent were quick to point out—fluctuated according to hearsay, was jacked up by speculators, and then ratcheted down by lazy tenants underbidding on a piece of property. Market price was informed by “all the motives” that might direct people to occupy land, including hope of speculative appreciation and the desire to profit from evictions and rack rents. Because of the constant supply of investors ready to buy land at high prices, rent never fell. Land auctions and land speculation resulted in “persons without sufficient capital” offering prices that they were “unable to pay,” thus driving up the price for all bidders, and subsequently driving up the price of rent for the tenants they required.5 Over the long term, speculation in land tended to result in a world where tenants were less and less able to pay the increased rent, leading to eviction and immiseration.

The alternative proposed by Irish theorists was a system where tenants negotiated the cost of rent or the price of land with each other, on the basis of perfect information about the conditions, be it the swampiness or cultivation potential, of a plot of land. If only tenants bid against other tenants, theory went, the cost of rent or the price of land would remain relatively modest. They proposed that Irish tenants harness the new science of geology and surveying, or “valuation,” to supply tenants with information about the potential profit and thus true price of a piece of land.

Irish theorists of rent increasingly insisted that the economy rested upon measurable labor—including the labor of tenant farmers who worked land that they did not own themselves. Tenant farmers, according to the Irish theorists of fair rent, were more than simple consumers of space: they also actively improved farms. It was their labor and education that turned a rocky field into fenced-in cropland, or a wasteland into a profitable farm. Tenant farmers’ contributions could therefore be measured, quantified, and turned into a set of numbers—which, they believed, should ultimately result in a rent reduction.

Thus, a theory of tenant-negotiated price, and a theory of measuring tenant labor, underlay the eventual rent control measures enacted in 1881. The success of the fair rent movement depended, to a great deal, on long-term commitments to these two theories, including the work done by geologists, lawyers, surveyors, and activists in collecting data about rents, eviction, and costs, and thus spelling out a viable path to enacting and fixing fair rents.

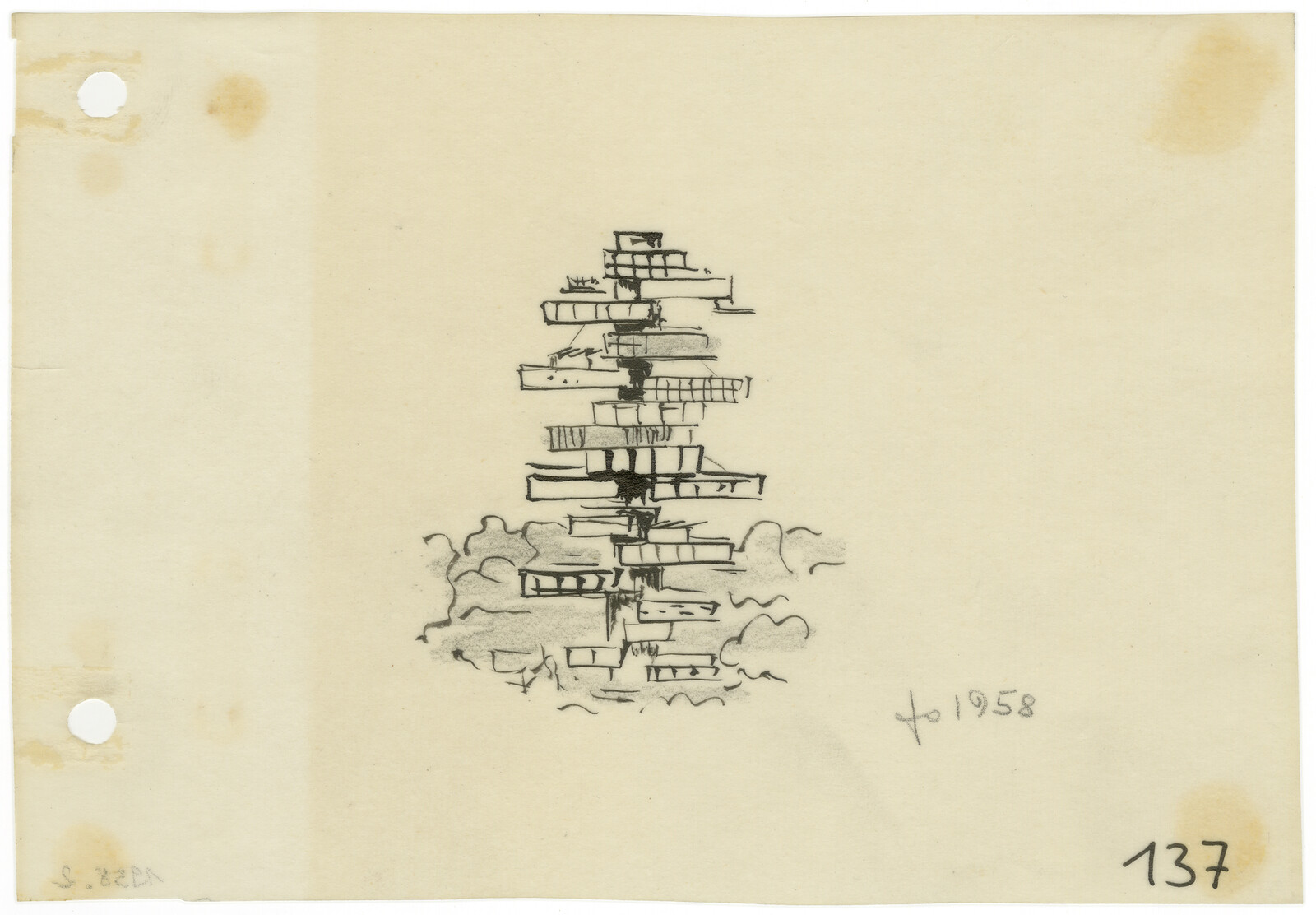

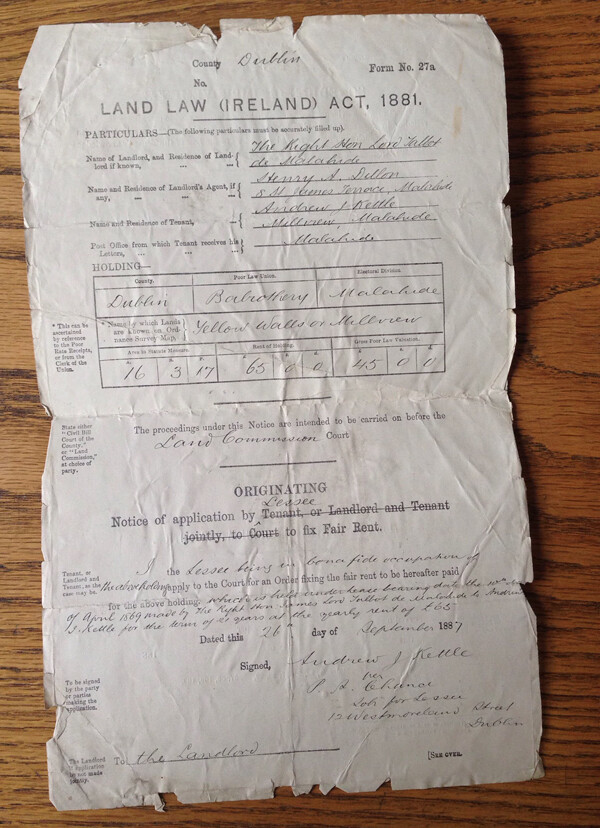

Application for fair rent under the 1881 Land Law. Source: National Library, Dublin, Ireland.

Valuers Rationalize Rents in the Name of Fairness

The possibility of “fixing” rents was available only because judges, Liberal parliamentary representatives, and certain leading figures in political economy agreed in principle to support a systematic rethinking of the price of land. This system, called “land valuation,” would play a central role in the debate over how rent should be controlled in the following decades. Its authoritative, scientific reappraisal of the economy would be used to create a free market in land that was livable by tenants, while eliminating the worst sins of increases in prices due to land speculation.

The ideas that would later form the system of land valuation first appeared in Ireland in the 1840s, at a time when Ireland was being surveyed by the British state for the purposes of taxation. Irish surveyors—who were often called upon to do the work of surveying—began to theorize how the land survey might serve social purposes, namely by providing reformers with a standard for a “fair rent.” In theory, a reformed government could use this data to officially peg the cost of rent and the price of land to realistic numbers that tenants could afford without suffering the threat of eviction.

According to early advocates of land valuation, the entire market economy was distorted because rent and land were treated not as a practical asset—the foundation of inhabitation and occupation—but as a market commodity whose relationship to a community might be purely financial, rather than marked by an investor’s own desire to set up occupation in one, which could thus allow it to increase exponentially in value. The division between occupancy and market investment, however, was not hard and fast: theorists of land valuation still expected tenants to treat the cost of rent and price of land as commodities that would be bid against each other. But occupancy was treated as a higher good than investment per se. “Absentee” investment, which bid the cost of rent and price of land higher than what locals could afford, was abjured in favor of conditions that favored local investment. In the model proposed by Irish idealists, investment that resulted in mass displacement was out. What was proposed, instead, was a local economy characterized by local inhabitants learning soil science for themselves, taking informed risks, improving their farms, reaping profits, and losing their investments where they failed.

With the 1881 Land Act, the Irish Land Court set something like this into action. The courts and their officials would determine an initial rent, typically one-third lower than market price, according to the professional valuation of a piece of land. Valuation represented a moral alternative to the social nuisances created by establishing a rent according to market price. And if a tenant felt that they were being asked to pay too much rent, they could apply to the Land Court for a reduction based on a court-appointed land valuer’s assessment of the property.

In order to do this, the court’s land valuer would travel from farmstead to farmstead, inspecting the farm, assessing the soil, and measuring the work that each tenant had contributed to improving the property: the manuring, draining, making of channels and fences, building of barns and chicken-coops. Thus rent control would be specifically tailored to each individual property. It was only on the basis of specific measures of each individual tenant’s contributions to the improvement of the property that a judge would deliver a ruling for reduced rent.

Valuation policies were adapted to appease both landlords—who expected a rational and market rent to protect contract and investment—and tenants—who expected that fair rents would be low enough to protect them from eviction, and that rationality would acknowledge tenant labor already exerted in improving a property. In carving out a process for lowering rents across Ireland from science-based price assessments, valuers became key figures of the new justice regime ordered by the Land Court. Their techniques and judgments were crucial for imagining a fairness-based economy that recognized tenant labor rather than landlord investment as a source of value.

The mechanism of a court entitled to hear claims about the fair price of rent was itself an innovation. Yet from the first meeting of the court, Judge John O’Hagan had announced that the Land Court intended to support a “live and thrive” rent.6 “Live and thrive” rent formed the first, hazy determination of whether the prices charged to tenants constituted a “fair rent,” to be approved as such by the Land Court, or whether a lower rent should be ordained. The judges and the tenants’ lawyers asked questions about whether a tenant “could live” at the present rent, or whether a tenant “paying the present rent of the holding would have anything left for the support of his family.”

Many landlords of course resisted the measures by publishing indictments of the economic theory and law behind the rent control. They were entitled to countersue the court, and to provide evidence for their claims, but the basic logic of the court—that a fair price could be determined on the basis of data—had already reset the rules of the game.

Countervailing reactionism still erupted from time to time. For a few years after 1886, a landlord-friendly government would attempt to reverse the culture of resistance, waging a war of terror on rent strikers in the form of a police army equipped with a battering ram, decimating the dwellings of the resisters. But peasants continued to resist, by leveraging public opinion via newspapers, social pressure via the practices of “boycott” and “shunning” (or mass social distancing, targeted at particular individuals who represented the landlord’s interest), and occasional acts of outright violence like assassination. Violence answered violence.

The alternative economy of rent control—the one proposed by Irish theorists and enacted by the courts—opened up an alternative to unending practices of violence. It also released Ireland from the constant ratcheting upwards of rent, marking out Ireland a space where rights of occupancy were favored over long-distance investment. In the decades that followed, Ireland became a mass social experiment with local, sustainable economics and the value of occupancy against displacement. Wealthy capital in many cases indeed left Ireland, with former landowners selling their real estate and fleeing to California or elsewhere. But, meanwhile, the system of land valuation made possible something extraordinary: the ratcheting downwards of rent, making it possible for ordinary tenants to live free from eviction, and the mass redistribution of property.

Valuation as an Alternative to Market Price

The work of “land valuators” or “land valuers” deserves to be understood as the origin of modern rent control as well as a major episode in the history of anti-colonial movements. Irish valuers, generally speaking, were men who typically had trained as surveyors but who applied to work for the Land Court system. Theirs was the task of assessing peasant land and describing, in detail, every culvert and chicken-coop built by a tenant in order to properly assess the tenant’s contribution to his own welfare, the landlord’s contribution to the land rent, and the “fair” price of rent. The entire success of the court in legitimizing fair rents—and thus making room for the continued functioning of the Irish agrarian economy—rested upon the valuers’ ability to persuade both tenants and landlords of the objective status of valuation.

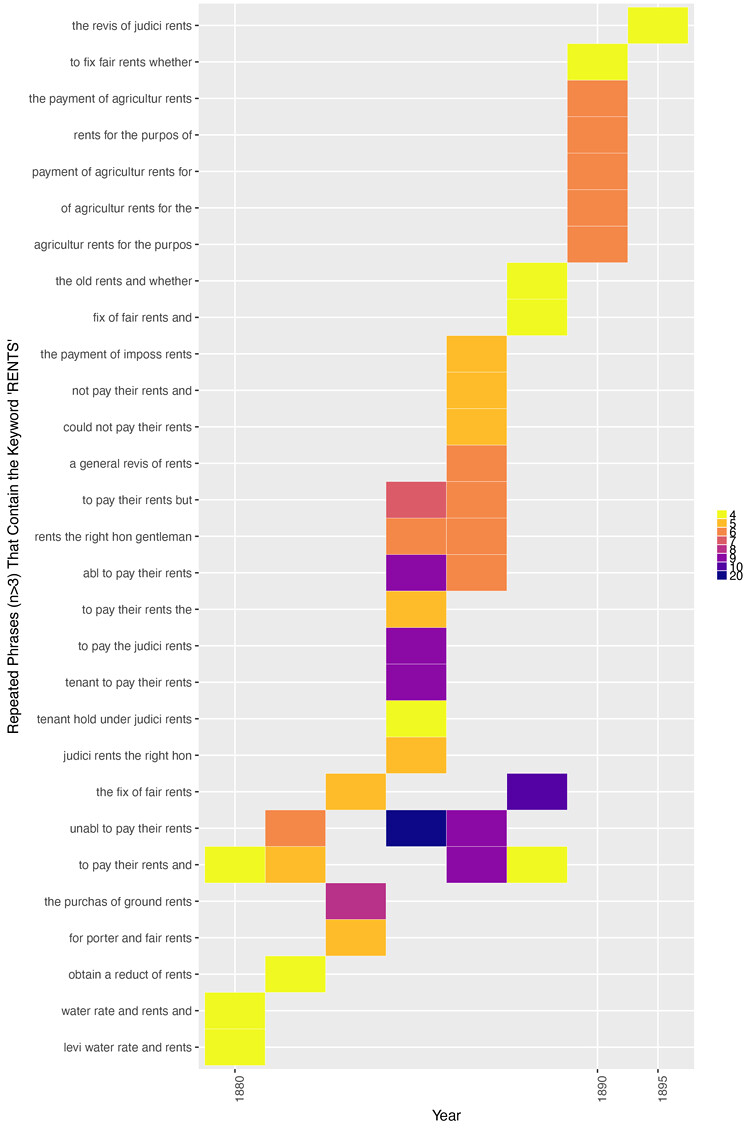

How “Valu*” (including “value,” “valuation,” and “valuator) was discussed in parliament from 1860–1903, showing recurring 5-word phrases. Darker colors indicate more often-repeated phrases. Horizontal movement suggests the replacement of one set of “memes” by another set of phrases. Note the prevalence of valuation in conjunction with “tenant right” and “tenant improvement” after 1870.

By the late 1890s, the land valuer had triumphed in parliamentary policy, becoming an integral part of British bureaucracy. In 1896, a new Land Act mandated that the Land Court disregard quoted hearsay of the price of land, now considered “popular evidence.” Instead, the courts were told to trust the “technical evidence” of valuers, the judge’s own opinion, and historical evidence of what had actually been paid by impoverished tenants.7 By 1898, valuers were acting as part of every subcommission in Ireland and even taking part in decisions as judges. Valuers’ notebooks documented every piece of land that went to trial at the Land Court, and judges regularly consulted these notebooks. In the Land Commission’s upper court (generally known simply as the Land Court), the valuer’s report was practically the only evidence permitted. Valuation had become the law of the land.8

The Spread of Rent Control

After the experiments in Ireland, rent control entered the lexicon of governments in England, Scotland, Australia, and North America. Social movements in Scotland and England demanded rent control and land redistribution measures like the Irish ones. By the 1910s, Gandhi was protesting high rents in Champaran. Landlords, discouraged by such rulings, gradually turned into investors rather than landowners, transferring their capital elsewhere.9 Rent control measures were eventually passed in Britain and North America, mainly in urban centers, as a means of protecting wartime economies.

Faith in rent control as a criterion of the flourishing of civilization persisted unchallenged until the 1940s, when a young Milton Friedman published his first assault on the welfare state in the form of a pamphlet entitled, “Rent Roofs or Ceilings?”10 Friedman argued, on the basis of his personal difficulties finding an apartment to rent in New York City at the end of the Second World War, that rent control distorted the housing markets of cities by creating a sub-standard housing pool. He believed that rent control disincentivized continued landlord investment, thus stifling the production of housing and the improvement of existing housing stocks. The neoliberal attack on the welfare state had begun.

By one measure of economic growth, rent control stifles innovation. But if we read Friedrich Hayek’s classical complaints about rent control, we learn the problem is that homes were “not provided for the right people”: that is, it failed to reward builders and investors, while it provided economic opportunities to tradesmen and service workers, whom Hayek considered the “wrong” sort of people.11 Would those workers contribute to economic growth when they had more disposable income? Likely so. The same could be said for the economies of developing nations; so long as they provide other opportunities for investors, protections against gentrification are important to ensuring the well-being of the people who live in a place.

Conclusion

This story of the origins of rent control is a Weberian one about the radicalizing power of the civil service in an age of imperial transition. Valuators and judges were working in the borderlands of traditions of liberation. Irish history of the Land War has tended to focus on “resistance” as a mode of political action. There is very little room for state bureaucracies in these narratives, except as the British state acted as the enforcer of utilitarian political economy, aiding and abetting evictions. The reform efforts associated with the Land Court have been the subject of little research, and the figure of the valuer is practically unknown. Perhaps, in the process of this accumulation of detailed social history from below, the dynamics of how peasant will was absorbed into the state has been ignored. The postcolonial bureaucrat falls outside of the caricature of the rebel beloved in stories about revolutionaries.

Yet “hastening” is what reformers do. In Max Weber’s own account, contemporaneous to the Land Court, bureaucrats were imagined to work on behalf of peasants and other citizens to open up access to power. In Ireland, the paper evidence of land valuators was collected at a moment when the old regime was being challenged. Through the workings of valuators and courts, the landlord monopoly on paper and thus on land and economy was challenged by new forms of political practice—not only incendiary violence in the countryside, but also reforms where radical paper flowed in all directions. As with the Pakistani tenants documented by Matthew Hull or the Xerox activists of the Nixon era narrated by Lisa Gitelman’s activists, valuators were radicals whose skill was the hastening of paper in the name of reworking power so that it obviated the landlord class. The Land Court’s reduction of rent set into play a moment of postcolonial reconfiguration, where even traditional categories of political economy like “price” could be reexamined from below and reworked from within the bureaucracy. When participatory movements from below ally with bureaucrats, they open up the possibility of redefining citizenship, access to power, and the value of land on their own terms.

It is also worth observing that, implicit in the Irish system of land tenure, was a set of values that in retrospect looks curiously environmental in nature, even while favoring the opportunities for individual initiative typical of capitalist systems. Tenants were encouraged to “improve” their individual piece of land; investing in soil represented a long-term investment in the public good and should therefore be encouraged. In the nineteenth century, of course, tenants were encouraged to cultivate the soil out of a sense of collective “improvement,” or the economic worth, of soil that had been turned with lime and manure. It is worth considering how contemporary land policies might deploy similar reasoning to offer reduced rents for care-taking of land and water.

The story of Irish rent control suggests that ballasting common values—like the protection of the environment—can work hand-in-hand with protecting ordinary people from displacement. These two values may be incompatible, but only so long as long-distance investment takes priority over the value of occupancy, such that wealthy investors from afar can bid up the price of land and cost of rent at any moment. The story of Irish rent control suggests that one of the most important mechanisms in fighting for a local economy is data, and the power of local people and institutions to ascertain for themselves a reasonable benchmark of what local people are able to pay and what their values are.

Never before have we had so many tools for collecting data about land, water, and popular values as we do today, in a world of widely-distributed satellite images, tools for mapping, and mass surveys. It is easily within the reach of ordinary persons to collect information on what their neighbors pay (or could pay) in rent or mortgages, or to survey one’s neighbors about what values they appreciate the most—whether, for instance, the freedom to pursue investment without limits is more important than clean air, clean water, freedom from toxic pollutants in the soil, or the leisure to enjoy one’s family and neighbors. In theory, a data-driven activism today could pursue some reform of prices and costs, bringing rent back into alignment with the values of the community.

Matthew Desmond, “Eviction and the Reproduction of Urban Poverty,” American Journal of Sociology 118, no. 1 (2012): 88–133; Matthew Desmond and Tracey Shollenberger, “Forced Displacement from Rental Housing: Prevalence and Neighborhood Consequences,” Demography 52, no. 5 (2015): 1751–1772; Matthew Desmond and Carl Gershenson, “Housing and Employment Insecurity Among the Working Poor,” Social Problems 63, no. 1 (2016): 46–67.

Bentley Brinkerhoff Gilbert, “David Lloyd George: Land, the Budget, and Social Reform,” The American Historical Review 81, no. 5 (1976): 1058–1066; Brian Short and Mick Reed, “An Edwardian Land Survey: The Finance (1909–10) Act 1910 Records,” Journal of the Society of Archivists 8, no. 2 (1986): 95–103; Ian Packer, Lloyd George, Liberalism and the Land: The Land Issue and Party Politics in England, 1906-1914, vol. 22 (Boydell & Brewer, 2001); David Coleman, “Rent Control: The British Experience and Policy Response,” Journal of Real Estate Finance & Economics 1, no. 3 (November 1988): 233–55; John W. Willis, “Short History of Rent Control Laws,” Cornell Law Quarterly 36 (1950): 54.

Gerry Kearns, “‘Up to the Sun and Down to the Centre’: The Utopian Moment in Anticolonial Nationalism,” Historical Geography 42 (2014): 130–151; Charles Dickenson Field, Landholding, and the Relation of Landlord and Tenant (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink, & Co., 1885), 287-8; A. M. Sullivan, New Ireland (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1878), 300, 328.

John Lanktree, The Elements of Land Valuation: With Copious Instructions as to the Qualifications and Duties of Valuators (Dublin: J. McGlashan, 1853); Henry L. Jephson, “The Valuation of Property in Ireland” (Glasgow: Read at a Meeting of the Association for Social Science, 1876); Murrough O’Brien, “On the Valuation of Real Property for Taxation,” Journal of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland 7, no. 55 (1878): 385-90.

Lanktree, The Elements of Land Valuation, 3

“Mr. O’Hagan and the Land Court,” The Star (October 10, 1882); “Opening of the New Land Court,” The Morning Post (October 21, 1881).

Fry Report, 18.

Fry Report, 17.

Patrick Cosgrove, “Irish Landlords and the Wyndham Land Act, 1903,” in The Irish Country House: Its Past, Present and Future, eds. Terence A. M. Dooley and Christopher Ridgway (Dublin: Four Courts, 2011), 90–109.

Thanks to Jen Burns for turning my attention to this moment.

Friedrich A. von Hayek, “Repercussions of Rent Restrictions,” in Economic Freedom (Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA: B. Blackwell, 1991), 309.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.