Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture featuring contributions by Arno Brandlhuber & Unprofessional Studio, Adrian Daub, Jo Guldi, Miranda Hall, Bijoy Jain & Vyjayanthi Rao, Renato Cymbalista (FICA) & George Kafka, Daniel Loick, David Madden, Frei Otto, Anna Puigjaner, Dieter Roelstraete, Hilary Sample, Lukasz Stanek, and Nathalie de Vries.

What does it mean to say that housing is a human right? Housing is more closely related to the feeling of home than to a house or any built structure. For decades, architects and architectural theorists have reckoned with the agency of building, and of building houses in particular, for the house is the most political building that can be built. But a house is not housing. A house can be owned. A house is a piece of property. Housing is something else. Housing is a right. Housing is not a question of ownership, but access.

To say that housing is a human right is often interpreted as a projective call. It is read to highlight a certain plight: the inhumane living conditions of so many humans. It is a call to improve our cities. But the call of housing cannot be answered through aesthetics alone. It is not even a call to build more houses—more “residential units,” as cities refer to them in demographic tongue. Housing is instead a call to radically rethink the foundations of the city as such. It is to rethink what it means to live together. It means to rethink who we are, and how we live together. To question housing is to question the human.

Housing is not just a right. Housing is right. Rights are never singular, or solitary; especially when the right is treated as property. Property is always a bundle of rights. Property gives its owner access to certain rights. Housing, then, is the bundle you hold. The house is a vessel, a transfer of entitlements, securities, obligations, and futures. Occupancy is to exercise the right of one’s housing. Ownership, however, is not used; it can only be given, or taken.

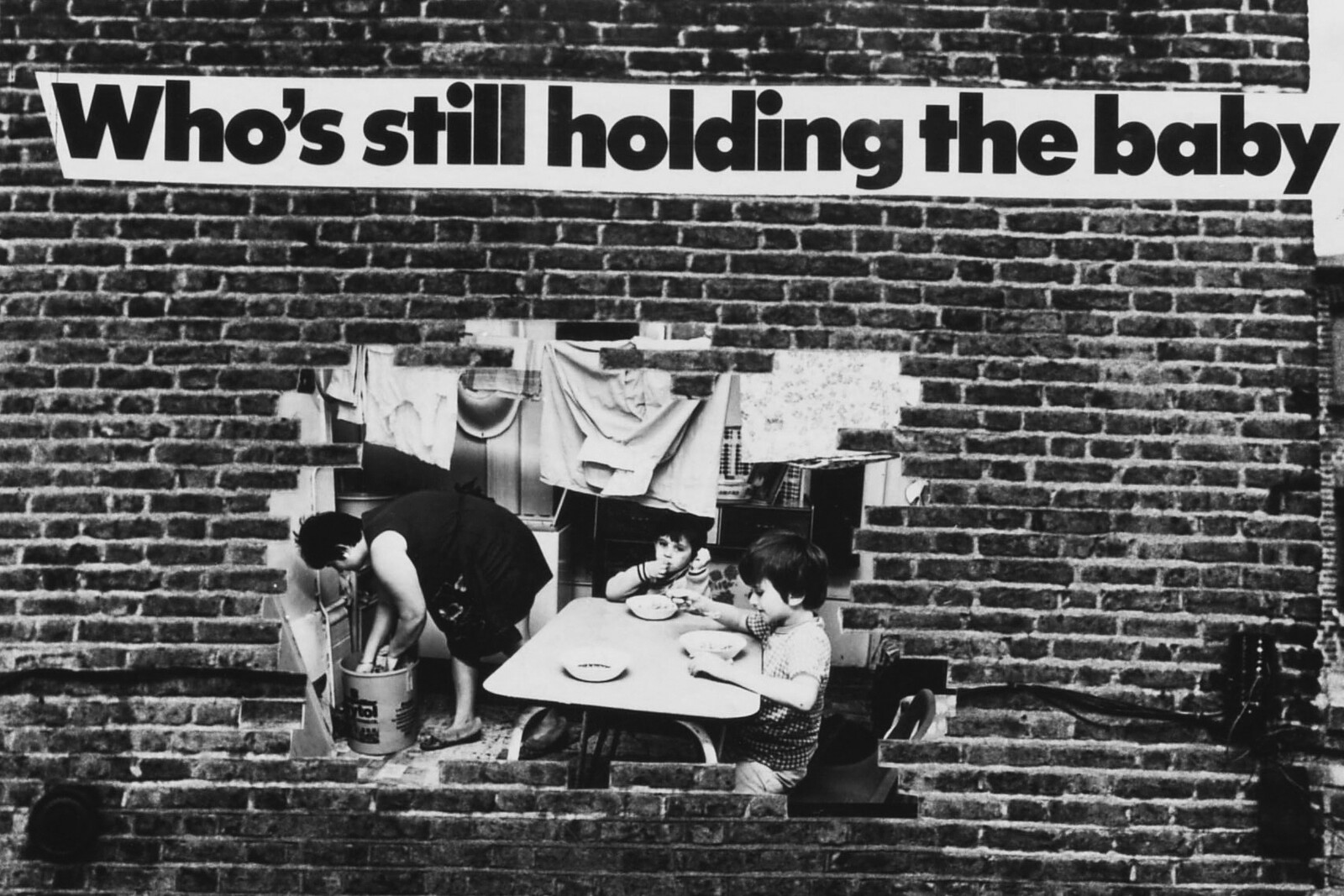

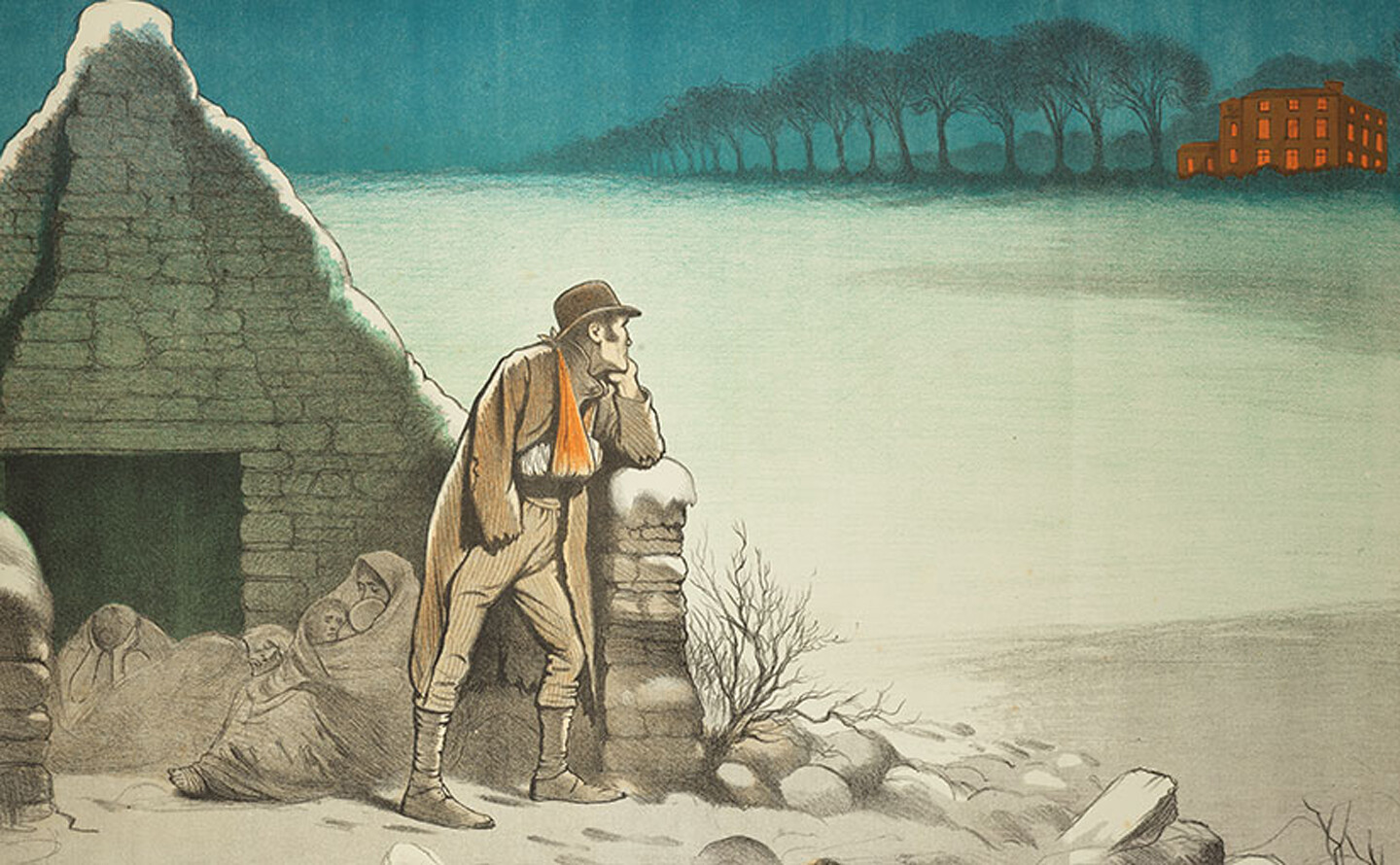

Throughout the world, over the past fifty years, conditions of access to housing have been increasingly relegated to the market. Housing rights activism in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries fought for better, less crowded, and more healthy living conditions alongside safe workplaces, a five-day workweek, and a fair wage. Faced with the widescale destruction of the built environment and the need to build at scale yet again, postwar welfare state governments expanded upon this political legacy of industrial revolutions under the aegis of “social housing” to ensure citizens were provided adequate, appropriate, and fair housing. It was in these years that housing, by becoming the responsibility of the state, became invested with not just economic accountability, but democratic promise.

For centuries, housing has been a medium for implementing social justice. As such, it has also been a locus for efforts to resist such politics. Starting in the late 1970s, newly-elected neoliberal governments worked to dismantle the institutions of social housing and erect new ones in their place. The neoliberal revolution rebuilt the meaning of the right to housing from the ground up. The legal right to housing—that which must be preserved, upheld, and maintained by the law—moved from the right to occupancy—a concept pertaining to the basic need for shelter—to the right to hold property.

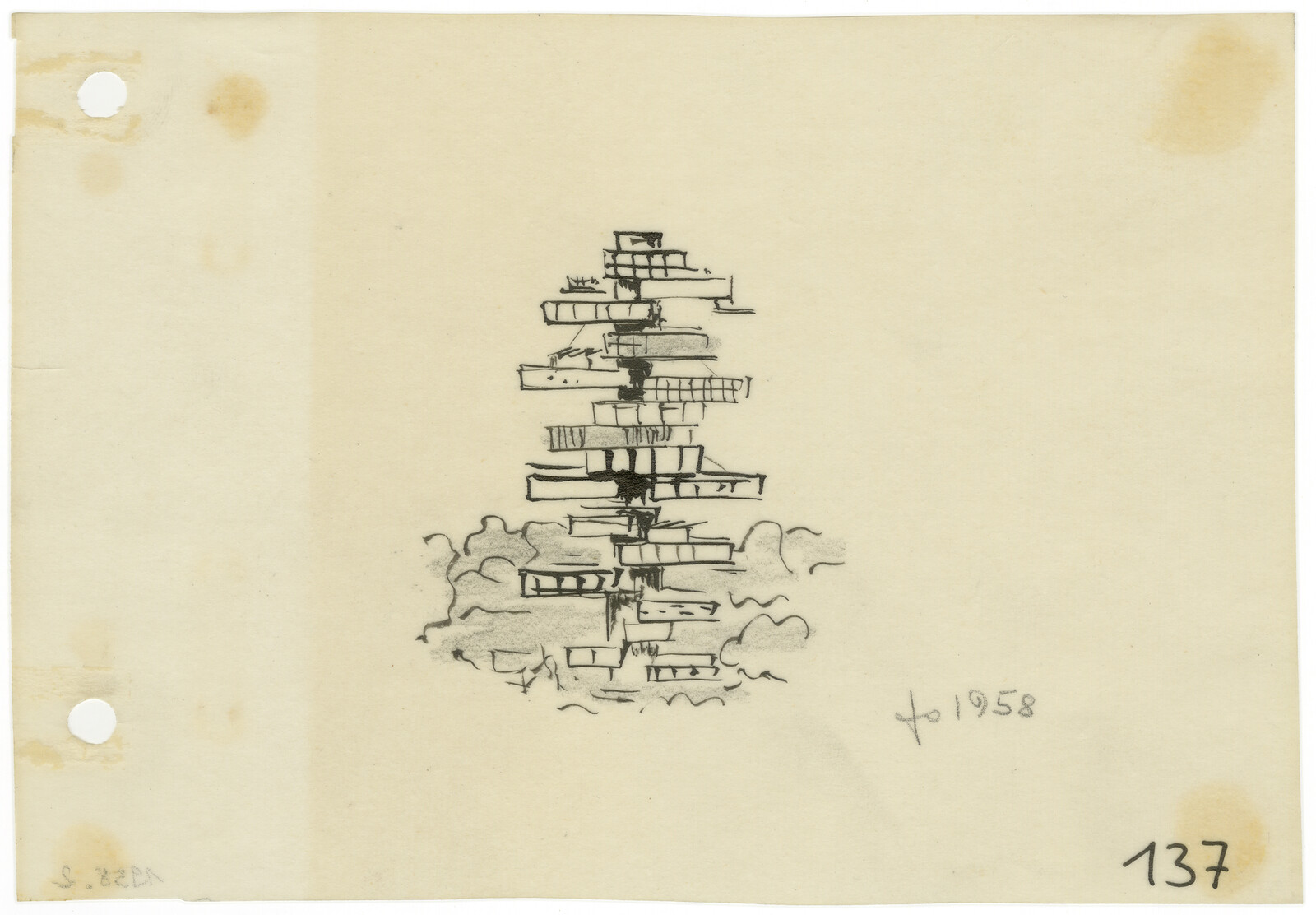

We do not need to know what property is in order to understand what it does, what its political economy has done. While the emergence of the housing question centuries ago already spoke of a crisis, the contemporary housing crisis is not only historically unprecedented, but almost unfathomable in both scale and violence. Alternative, self-determined architectures of housing might ultimately be incapable of addressing the dimension of the problem, but they do offer important ideas, values, and principles that have the potential to act as lines of flight away from the permanent crisis that housing has become. At the same time, important work is being done around the world to undo neoliberal unhousing. The establishment of new structures, new institutions, and new relations allows for a more collective, more just future to not only be thought, but also lived.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.