The North American Rift was discovered shortly after the end of the Great War, when it bisected a tractor on the morning run. Initial, informal tests revealed a stable two-sided, two-dimensional ovoid opening in the air that linked a field in the Midwest of the United States to an arid region in some unknown place. Early information about the discovery was slow and disjointed in its spread. In the confusion, a local surveying firm hastily organized an expedition to gather some information. Their results were astounding—an entirely new, uninhabited world, with a commensurate bounty of resources:

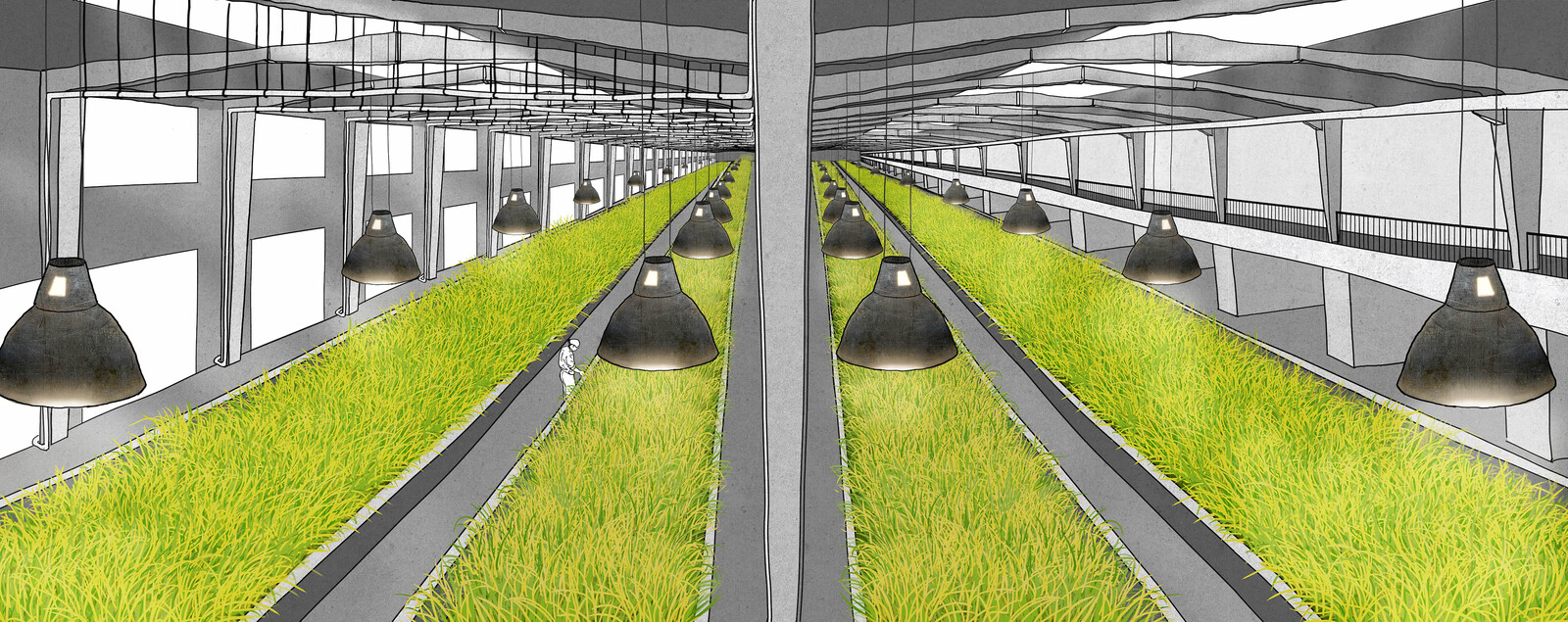

The stars in the sky are foreign from our own, but in all other ways the region of investigation seems to be adjacent to the geography and clime of our home country. With no sign of other inhabitants, the terrain is lush with untapped resources and hints of exotic new material. A figure of ambition would have unparalleled opportunity to establish themselves and make something new.

Emboldened by the promise of unclaimed fortune, as well as the apparent lack of official response, the surveying firm purchased the land around the rift and started to issue land vouchers and industry permits for extracting resources—minerals, lumber, livestock, crops—on the other side. Word of this started to spread quickly. Enterprising businesses, investors, and individuals all began to rush to the rift in a bid to stake their claim on the newfound territory.

With this sudden migration, the government was forced to take notice. Still embroiled in negotiations surrounding the Treaty of Versailles, the uncharted lands on the far side of the rift were marked as a simple unorganized territory. The firm that owned the surrounding land was issued a charter, allowing them to oversee administrative functions as well as provisions for handling travel from one side to the other. Its small team of surveyors reorganized into the Manifest Destiny Trading Company, and the initial camps that surrounded both sides of the rift quickly grew into settlements, towns, and thrumming cities: Culmination in the United States, and Outset in the frontier.

***

In the early years, the territory appealed mostly to former soldiers or drifting adventurers; people who had nothing left or were trying to escape. The Company eagerly scooped up these vagabonds and set them to work building in the frontier. Unemployed pilots were tasked with surveying and preparing the earliest maps, which general laborers used to construct railroads that wandered out over the horizon without any specific destination, just the promise of future utility. Companies across the globe recruited down-on-their-luck individuals and shipped them through the rift and out along these rail lines to work in mines, lumber yards, or ranches with the promise of fortune and glory after a few months of labor.

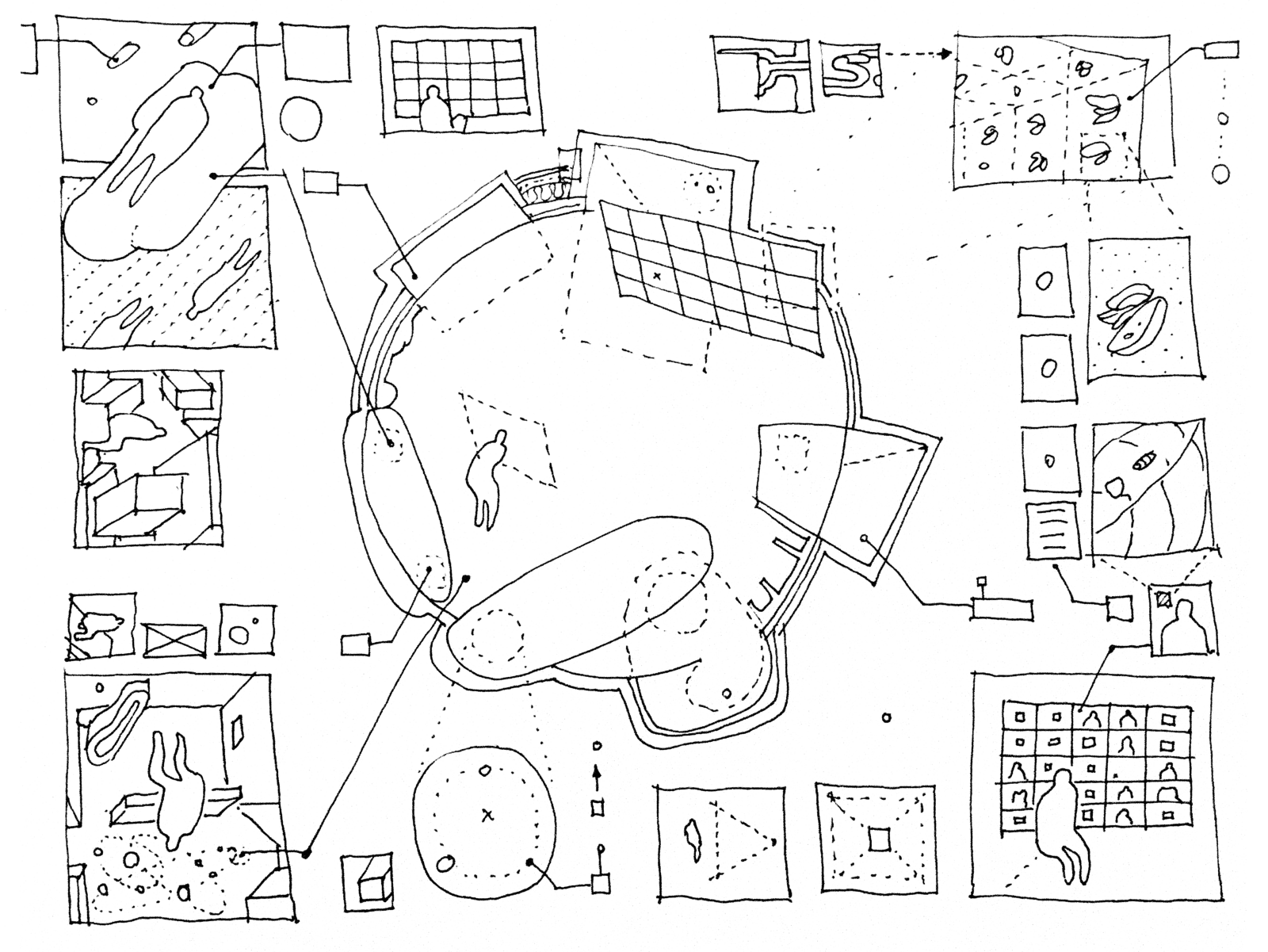

Initial traffic through the rift went by foot, with crossing being staged in a small clearing with space for trucks, wagons, and the occasional horse to pass through. As pedestrian and industrial traffic in each direction began to build, however, this rapidly proved insufficient. To facilitate the expedient movement of goods and people, the Company organized a convoy of small vehicles that is loaded with cargo, travels through the rift, unloaded, refilled with goods from the frontier, and travels back, unloads, and repeats. This, too, sufficed for a time, but the swell of eager participants, valuable raw goods passing back through the rift, and manufactured equipment being shipped to the frontier proved too great. Losing money and time to the perpetual slowdown and ever-growing queue, the Company knew they had to find a more permanent solution.

Following months of preparation and engineering, transfer was temporarily limited to high priority goods. Then, over a period of a few days, a veritable horde of construction personnel descended upon the site—on both sides of the rift—to assemble a more technologically sound and future-proof version of the vehicular convoy. To handle the present and predicted volume of transfer, the Company designed and constructed a closed length of rail that would continuously move at moderate speed, looping through each side of the rift. Specialized containers, shaped exactly to the dimensions of the rift, were loaded as full as possible, moved onto a transfer car, and passed through the rift, where they were immediately pulled aside to be unloaded, the car reloaded with a new container, and sent back once more.

In effect, a near-solid volume of material started to pass through the rift at a few miles per hour. With the transfer loop moving at constant speed, cargo space came to be sold by the number of seconds required for the volume to pass through—typically in multiples of three and a half seconds, the time required by a standard container. Great effort was paid to maximizing the packed volume of containers: ores than could not be processed in the frontier were ground into a fine sand; tools and equipment were shipped flat packed and assembled on site; luggage was packed in specialized suitcases at a set fee, and so on.

The unusual ovoid dimensions of the rift and the made-to-fit shipping containers had consequences throughout various manufacturing industries: oddly proportioned lumber required resizing; pre-slaughtered livestock demanded advances in temperature-controlled shipping; pulverized ore reorganized traditional metallurgic sequences. But perhaps even more importantly, widened containers that were well suited for efficient transfer through the rift did not fit in pre-existing handling bays. Adapting to goods shipped from the frontier required enormous cost, as entire manufacturing plants, transport stations, and distribution facilities had to be retooled and resized.

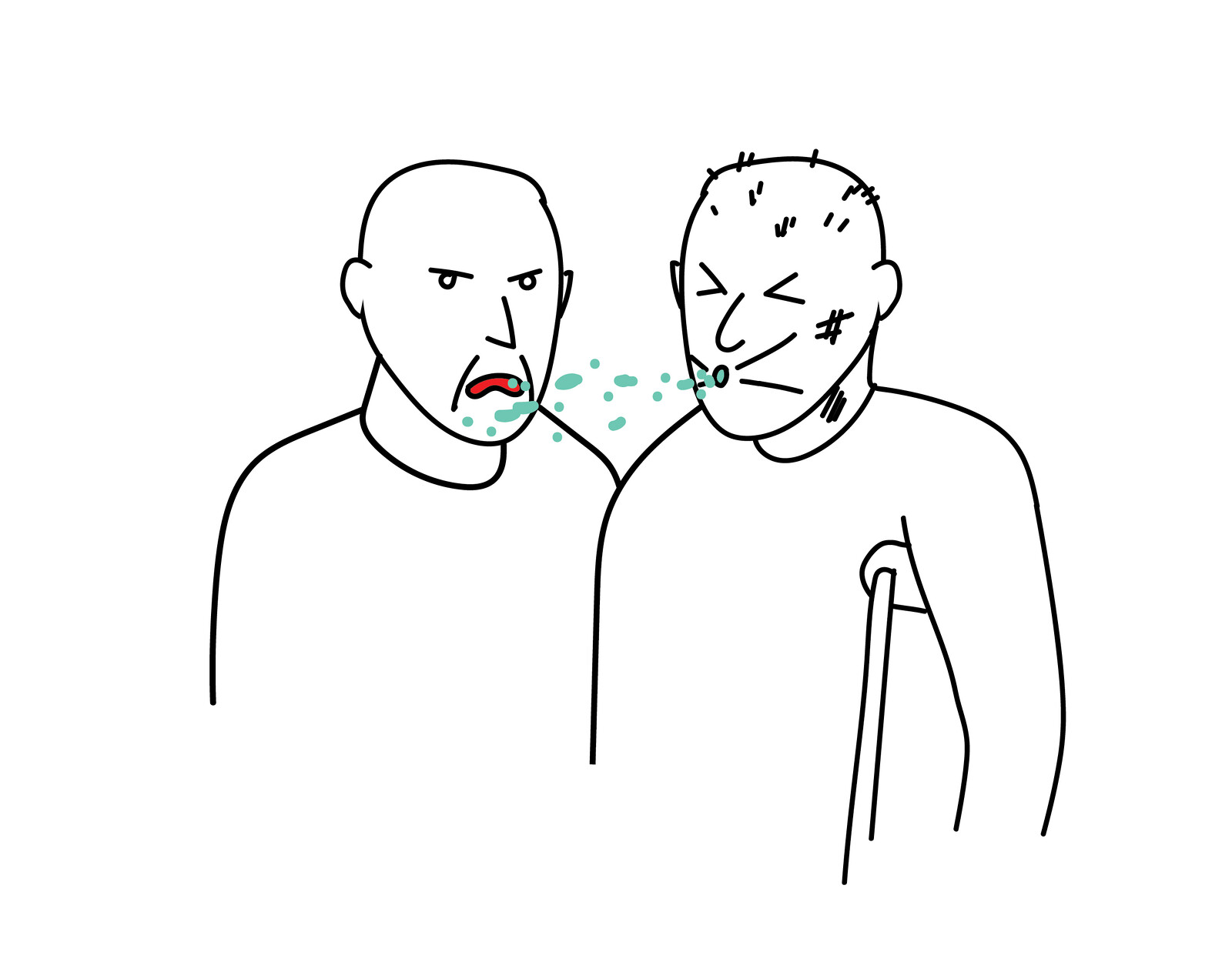

Pedestrians—notoriously incompressible as they are—posed a challenge to the ruthless efficiency possible in the transfer of other goods. The cost-effective solution that resulted meant standing packed shoulder-to-shoulder with a batch of other passengers, luggage otherwise stowed, in a tiny car for a up to an hour while waiting to be shuffled through to the other side. The actual transfer takes place in a matter of seconds; it is only a matter of slotting a passenger car into unceasing queue of packed containers. Fortunately, given that the standing volume of a person only had to compete with a comparatively small quantity of unprocessed minerals, individual tickets have remained in the realm of possibility for those with the desire to cross over, given they can tolerate a brief, uncomfortable ride.

***

For many veteran families, opportunity and stability failed to materialize at home the way they had imagined. Faced with overcrowding, rising land costs, and growing unemployment, these families sought an alternative to fruitlessly scrabbling over the inadequate openings that remained. First by word of mouth, and then by ceaseless advertising campaigns, knowledge of the rift, its promise of opportunity, and the Company’s generous terms of settlement spread into the rest of the country.

The Garcias were one early family to gather their possessions and pass through the rift, destination unknown, based solely on the whispered promise of potential on the other side. Arriving on the other side of the rift in what was then the haphazard tent city of Outset, they exchanged their savings for a set of farming implements and a scrip guaranteeing them a certain acreage of land. Boarding a train with no clear endpoint, they took their time surveying the southeastern frontier by rail, weighing the benefits of the vast breadth of unoccupied land they passed, eventually settling on a plot of fertile land nestled between a range of mountains and a bend in the line.

Following a year of early success tending their land and selling their surplus to entrepreneurs at the irregular informal station-side markets, the Garcias wrote enthusiastic letters to their friends and acquaintances back home, extolling the incredible prospects available for work. Gradually, these people filtered through the rift and, following the advice of their friends, came to settle nearby. This small group of families clustered around a rail stop soon expanded their improvised buildings into permanent structures and dubbed the location Flores.

Further settlers took notice of the Garcia’s pleasant farming community as they too sought a place to establish themselves along the southeastern rail. People not interesting in farming or maintaining livestock set up other business as merchants, craftspeople, doctors, and teachers, forming a link between the agrarian production and the other forces of civilization spreading along the rail. As it grew, Flores became a jumping off point for anyone seeking to move deeper into the frontier.

Flores’s expanding population and swelling itinerant workforce caught the attention of the Burnett Grinding & Crushing Company. Flush with raw material from a productive mine further down the line, the Burnett company needed a location to process their ore in preparation for shipping it back through the rift. The factory attracted many potential settlers who found the lure of the agrarian life fleeting, choosing instead to stop on the edge of the frontier. Flores continued to expand as Burnett and their industrial competitors sought to leverage the population of eager workers.

Years passed, and Flores expanded into a respectably sized city—ultimately attracting a library, research institutions, countless factories, independently owned farms, and even a burgeoning high society. It became fashionable for tourists from the old world to visit and see “real frontier living,” despite the fact that the true edge of the frontier had traveled down the line long ago. As the rail grew increasingly lengthy and populated, the Company selected Flores as the site for a major fork in the line, ushering in a new wave of development into hitherto unsettled regions. Less than a generation after Flores’s first settlers choose a plot of arable land, their small community has exploded into a thriving city, the gateway to the southeastern frontier.

***

Initially, the settlements near the rift in the United States experienced a similar story. On their way to investigate the rift, the very first team of surveyors spent a night in the hospitality of a farming family in the nearby town of Orwin. This family home—the Townsend’s—became a common stopping point for early Company officials. The Townsends, encouraged by the steady flow of guests and the assurances of Company officials that this was going to be big, cut down their trees and erected some simple lodgings to rent.

As the first accommodations anywhere close to the rift, the Townsend farm established Orwin as the premier stopover spot for travelers headed to the frontier. Emboldened by the success of their neighbor and friend, other families in Orwin began variously selling off their now valuable land or building their own businesses catering to travelers—lodging, restaurants, last-chance supplies, and so on. The formerly narrow and undermaintained dirt track that served as an access road to the rift swelled into a lively highway, facilitating the steadily growing traffic.

The denizens of Orwin suddenly found themselves in positions of great wealth and significance. All of the early industrialists, adventurers, and settlers voyaging through the rift spent the last of their preparatory money in what had become a boomtown, replete with hastily erected department stores, a resort, and a broad boulevard on which a steady stream of vehicles rolled past. The Company acquired choice segments of Orwin’s former farmland and began to formalize the connections with the rest of the country into a more ordered and manageable rail network.

Following the completion of the continuous rail loop traveling through the rift, traffic dramatically increased. While travelers and industrialists had previously needed to wait as much as a day or two to have their goods transported, the wait time was now reduced to nearly zero. With the advent of this connection, raw material flowing from the frontier no longer needed to pile up directly adjacent to the rift, and instead was immediately routed to hungry factories across the country and the world.

Orwin, initially anticipating a boon of new consumers in the wake of the completion of the transfer station, found that pedestrian traffic dried up at a startling rate. Travelers heading to the frontier took a direct train from their hometowns on through to Outset, and the corporations shipping commodities backwards used the same rails with no need to stop locally. With no people and no farmland, Orwin was unable to maintain its bloated size.

Gradually, once-resplendent businesses closed their doors and fell into disrepair. Non-descript warehouses spread out miles away from the loop to handle the increased traffic of material. The last of Orwin was ultimately swallowed up by the need for storage. Some took their savings and tried to start over on the other side, while others sought new opportunities close to the rift. But by and large, long-term success passed the citizens of Orwin by.

***

Today, some twenty years after the initial discovery of the rift, civilization is gradually taking over the frontier. Outset is a bustling metropolis, headquarters of the impenetrable Manifest Destiny Trading Company and jumping off point for the constant steam of eager hopefuls looking to make a new life. The rail lines, once desolate projects starting and ending in nowhere particular, have become dense paths of cities, trading posts, crossroads, and industry. Enduring prosperity for those who remained in the old world and attempted to capitalize on the boom remains fleeting; the economic giants who could endure the initial shock grew even wealthier, while the smaller, more independent businesses who did not have the stability to react found themselves excluded and fell further behind.

The territory between the lines remains comparatively remote, but with each discovery and promise of wealth to be made a branch of a nearby rail thrusts into the wilderness, drawing a path for more settlement to follow. As the edges of the frontier are pushed further and further away from the rift, its denizens are starting to face tough questions. For people defined by the ongoing pursuit of the horizon, what remains to strive for when the horizon has been caught?

Cascades is a collaboration between MAAT - Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology and e-flux Architecture.