In 1885, King Leopold II achieved an astonishing and improbable goal: he claimed a vast new realm of his own devising, a conjury on a map called “L’État Indépendant du Congo,” the Congo Free State. First an international congress and then the Belgian parliament authorized the king to become the sovereign of this distant African entity; parliament provided loans to fund it as an arena of investment and extraction. Only one deputy voted against it. Thus was born what historians have called an anomalous colony without a metropole: a fictional state owned by the king, ruled by decree, and run from Brussels from 1885 to 1908. While the king became the absolute ruler of a foreign realm in Africa, he remained a limited constitutional monarch in Belgium under the ambiguous legal terms of a “personal union” (“union personnelle”).1 This was not a settler colony propelled by a national mission, but a private entrepreneurial venture. The abundance of ivory, timber, and wild rubber found in this enormous territory brought sudden and spectacular profits to Belgium, the king, and a web of interlocking concession companies. The frenzy to amass these precious resources unleashed a regime of forced labor, violence, and unchecked atrocities for Congolese people. These same two and a half decades of contact with the Congo Free State remade Belgium—what was then a new, small, and neutral country, squeezed and exposed on the map of Europe—into a global powerhouse, vitalized by an economic boom, architectural burst, and imperial surge.

Congo profits supplied King Leopold II with funds for a series of monumental building projects in Belgium that he commissioned in a style that could be called “grandiose eclecticism.” A cluster of modernist architecture was also made possible in part by the profusion of wealth flowing to elites entangled with the king and the Congo Free State. Indeed, Belgian Art Nouveau exploded after 1895, created from Congolese raw materials and inspired by Congolese motifs. Contemporaries called it “Style Congo,” but I characterize it elsewhere as “imperial modernism” and call it “Art of Darkness.”2 In this essay I focus on how King Leopold II colonized Belgium’s public urban spaces. The inventory of this royal architecture is astonishing not only because of the buildings’ massive scale, unlimited budgets, and massive work crews that were deployed to complete them in record time. Within them are also the shaping presence of King Leopold’s architectural theory, formed early and pursued determinedly for decades, and the interaction between the king and the dexterous and devoted elites who rallied to the African enterprise and made it work.

While presumed to be concrete expressions of what has been called a “megalomaniacal king,” the architecture erected during the last decade of the nineteenth century in Belgium was a team effort of cronies and confederates willing to follow the money from the “Congo Crown Treasury,” to adjust procedures of law, and to subvert the rules to pave the way for the king’s will and wishes. At the hub of both the king and his associates is “tentacular capitalism,” of which Leopold II was a prescient and early practitioner.3

This essay proceeds in two parts, tacking between past and present. Part I draws from historical research that recovers Leopold’s formative ideas of architecture as power, his unrelenting efforts to implement them, and his inability to do so in a country where the “King of the Belgians” had severely limited political and symbolic prerogatives. Leopold’s absolutist rule over the Congo Free State changed his status as a monarch in Belgium in unexpected ways, yielding the monumental and permanent building program he had long hoped to realize, with irrevocable impact on Brussels, Antwerp, and Ostend. Facilitated by loyal elite coteries, Belgium’s imperial occupation of the Congo made possible the king’s coveted architectural annexation of public space at home. Part II explores a number of ways contemporary artists are now wrestling with how to dislodge that history in the built environment and public visual culture.

Part I: “Stun Funds”: Shock and Awe in Brussels

King Leopold II harbored lifelong ambitions to “embellish” and beautify the nation of Belgium with splendid architecture. As the young Duke of Brabant, he spent almost a decade trying in vain to rouse his compatriots to engage in large scale projects for this art du dehors (“art of public space”). Inspired by his travels abroad and Napoleon III’s renovated Paris, Leopold began his reign as king of the Belgians in 1865 overflowing with ideas for how to transform Brussels into a modern metropolis of monumental grandeur. Prime Minister Charles Rogier was initially startled by the enormity of his plans and grew increasingly apprehensive as the king pursued them with relentless tenacity. Rogier reminded Leopold that communal and municipal authorities administered the work of urban development—not the king. Belgian constitutional restrictions prohibited the monarch from a directive role. But Leopold had little interest in Roger’s suggestion that he join commission meetings of these varied groups.4 He remained bound to his idée force that architecture not only projected but also invented the nation.

Leopold’s was a sophisticated and coherent vision of what he considered not simply the aesthetic, but the strategic power of architecture. In choosing to “gild,” “adorn,” and enhance physical structures, Leopold argued the new nation would reap the benefit of shock and awe: visitors to Belgium would come away surprised and “stunned” by strikes of brilliance when they least expected it, their eyes captured by the force field of magnificent buildings. In a remarkable statement in one of his early speeches, young Leopold emphasized that capital expenditures were needed for what he called dépenses d’éclat (“stun funds”)—funds to maximize dazzle and display. These, he stated, were as or even more important for the reputation of a country than “a whole code of laws.”5 Despite his pleadings, King Leopold II saw the gigantic Palais de Justice as the only major contribution of Belgian architecture in the 1880s. This massive structure, designed by Joseph Poelaert, embodied the system of laws over royal prerogatives. Its monumentality represented the spaces enforcing Belgium’s constitutional rules, central to which were those that constrained the king’s centralizing power.6

Before 1900, the king’s architectural theory and grand plans for urban design were largely thwarted by municipal regulations and a lack of funds. But after 1900, with his personal treasury flush with Congo revenue, Leopold had free rein to construct lavish buildings, parkways, and palaces for Belgium. The built environment of Belgium was thus dramatically and permanently altered.

View of Alphonse Balat’s Greenhouses at Royal Estate at Laeken. Source: Herman Balthazar and Jean Stengers, eds., La Dynastie et la culture en Belgique (Antwerp, 1990), 200.

Charles Girault, plan for another greenhouse for palm trees at King Leopold II’s Royal Estate at Laeken, 1907. Source: Herman Balthazar and Jean Stengers, eds., La Dynastie et la culture en Belgique (Antwerp, 1990), 201.

Alphonse Balat, plans for Congo greenhouse at King Leopold II’s Royal Estate at Laeken, 1888. Source: Herman Balthazar and Jean Stengers, eds., La Dynastie et la culture en Belgique (Antwerp, 1990), 203.

View of Alphonse Balat’s Greenhouses at Royal Estate at Laeken. Source: Herman Balthazar and Jean Stengers, eds., La Dynastie et la culture en Belgique (Antwerp, 1990), 200.

By 1905, profits from the Domaine de la Couronne (“Crown Estate”), nimbly structured by chief financial operative Edmond Van Eetvelde, enabled the king to rebuild Brussels as an architectural Gesamtkunstwerk, the stage set of a global empire. Writers note that Brussels had two histories as a city: one before, and one during and after King Leopold II.7 At his Brussels estate at Laeken, Leopold—now the Roi Bâtisseur (“Builder King”) he long aimed to be—planned renovations explicitly designed to outdo Louis XIV’s Versailles. Enormous greenhouses contained flora from every corner of the globe, with a dedicated soaring structure completed specifically to house the oversize palms of the Congolese jungles. The surrounding parkland was not neglected: Leopold imported teams of artisans to reconstruct a large-scale disassembled Japanese tower and Chinese pavilion that he purchased at the Paris Exhibition of 1900.8 In the center of the city, fronting the Royal Palace, the king reassembled another structure he bought at this same venue, a Norwegian wood chalet. He used this building as a set of offices dedicated to ruling his African domain, complete with its own public relations bureau to counteract negative press reports about abuses against Congolese natives. A short distance from here was the Rue Brederode, which became known as “the Downing Street” of Belgium, except that it was not a site for government agencies, but the headquarters of the king’s allies and associates in the numerous investment and trading companies that sprang up to extract the seemingly unlimited treasures of the jungle. Among those occupying these Rue Brederode offices were Captain Albert Thys (who interviewed Joseph Conrad there for a job piloting a steamer on the Congo River), Émile Francqui, Alexandre Delcommune, and Adolphe Stoclet.9

The king’s Congo revenues also subsidized the completion of one of his pet projects for Belgium: a triumphal arch set at the edge of Brussels’s jubilee park, called the Cinquentenaire, which was conceived to be triple the size of Rome’s Arch of Constantine and exceed the scale of Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate. The Cinquentenaire Arch had long been a source of particular frustration for Leopold. Originally designed for Belgium’s fiftieth anniversary in 1880, the arch was only partly completed and left unfinished. This hulking fragment, a dismembered gateway to Brussels’ ceremonial urban zone, was a constant and visible reminder that, in Belgium, the king’s wish could not command: despite relentless hectoring, governing municipal bodies refused to fund the completion of the arch for more than two decades. It was only for the 1905 jubilee that Leopold was able to assemble a shadow group of financial benefactors who offered the city the “gift” of a new, massive stone arch, surreptitiously funneling monies for it accrued from the king’s Congo treasury.10 But even still, Leopold was prohibited from placing his personal initials, “L II,” on the arch that celebrated the nation’s “unity in strength” as nine provinces, each with its own coat of arms.

Inauguration of the Cinquentenaire Arch September 27, 1905. In center, King Leopold II with the group of “generous donors.” Source: Liane Rainieri, Léopold II Urbaniste (Brussels, 1973), 137.

The enormous middle arch set up an imposing architectural link between the city of Brussels and the king’s domanial property at Tervuren, once the estate of the Dukes of Brabant. The arch’s central columns formed a dramatic sightline from the Cinquentenaire to Tervuren that terminated at another colossal structure, under way in 1905, to celebrate the ravenous reach of the new Belgian imperialism: the Royal Congo Museum. Leopold lavished unlimited budgets from his Congo treasury on architect Charles Girault for the project, and together they designed an enormous complex, with a Congo palace modeled on Paris’s Petit Palais as centerpiece.

The Tervuren Congo palace site, and the dramatic sightline pulsing toward it, took shape in two phases, in which the king and inventive entrepreneurs worked together for their mutual benefit. First, in 1897, the king enlisted industrialist Edmond Parmentier to construct an efficient and modern roadway to connect Brussels to the Congo pavilion at Tervuren for the World’s Fair taking place there that year. Electric tramways were built and a wide swath of avenue emerged. Edouard Empain, who was a prime mover in the king’s railway enterprises in the Congo Free State and in Egypt, joined the venture as head of local railway services. Leopold demanded that the Tervuren roadway be eighty-eight meters wide to accommodate not only trams but also bicycles and motorcars, two of his passions. Parmentier balked, and set the measure at sixty. They finally agreed on seventy-six meters when the king made Parmentier an offer that was hard to refuse: just as he offered monopoly concessions in the Congo Free State to Belgian companies, he gave Parmentier exclusive rights to business in the area for fifty years. Leopold intervened personally again, and successfully, to persuade the local councils to plant 910 of his preferred trees to stand as sentinels along the elegant avenue towards Tervuren: only white, full flowered Indian chestnuts would do, as they were expansive, broad, and lush. Tall trees, the king insisted, would obstruct the linear corridor toward the terminus at Tervuren.11

With the success of the 1897 exhibition, Leopold set to reconstructing the area from the edge of the Cinquentenaire towards Tervuren. As he devised plans for the Congo palace and the approach to it, real estate developers began to break up lots for transforming the charming hamlets nearby into parcels for suburban mansions and gardens. Between 1902 and 1910, new neighborhoods with luxury homes appeared along the Avenue de Tervuren, affording modern conveniences and new railways for easy access to and from the city. Baron Empain even installed a first-class car lined in mahogany with drinks and decks of cards for the journey. Leopold also negotiated the widening of Avenue de Tervuren’s terminus at the entry to his estate and palace by providing some extra funds and parkland access. Prosperous elites began moving toward Tervuren, some through the investment yields from Congo trading, commodity, and banking companies. The opulent new neighborhood, another result of the Roi Bâtisseur’s architectural power and imperial windfall after 1900, could be called Congo adjacent.

The 1905 axis of the Cinquentenaire to Tervuren dramatically shifted the orientation of the city of Brussels and redirected the urban sightline. Here Leopold accomplished an architectural coup d’état through his newly unlimited dépenses d’éclat, which permitted him, as he had long wished, to gild, adorn, and thereby overwhelm the viewer with the sparkle and magnitude of buildings. These he had considered to be even more important for the renown of a country than “a whole code of laws.” His surreptitiously constructed Arch of Triumph realized this vision, and altered the meaning and function of the structure in relation to the ruler and the nation. The Arch of Constantine, on which the Brussels arch was based, had been erected by the Roman Senate to commemorate Constantine’s victory in battle; it spanned the Via Triumphalis, “the way taken by the emperors when they entered the city in triumph.” Leopold’s arch, conversely, was hidden from the senate to override constitutional restrictions on the Belgian monarch’s symbolic and political prerogatives. Funded by the Congo treasury through his business associates, Leopold’s via triumphalis marked the way taken by the ruler as he exited the city toward his estate outside it. The arch and its splendid avenue reversed the direction of its classical precedent, propelling the eyes of viewers and citizens toward the royal terminus. If the king could not rule the state, he could occupy and annex the nation’s real estate. Financial bounty from imperialism in the Congo Free State allowed him to do just that.

By 1905, la Belgique en éveil (“Belgium rising”) had reached its apogee. Leopold boasted in his jubilee year speech to the senate that, with its economic boom, architectural burst, and imperial reach, Belgium was now “close to having its own Parthenon,” while reminding his audience that even the “small nation” of classical Greece had originally created a “petit monument.” Now, he asserted, Belgium had its own conspicuous brilliance and magnificence and would “prove” to the world that Belgium was not small; any visitor who came there would be forced “to forget the smallness” of the smallest nation in Europe.12

While Brussels may be the best-known site of the monument splurge financed by Congo revenues in the decade after 1895, cities across the nation were also swept up in these architectural transformations. Two of the most important were Antwerp and Ostend, where Leopold and other Congo investors poured a sudden profusion of funds into outsized structures that indelibly marked their urban environments.

Contemporary postcard, n. d., showing the 1905 Antwerp Train Station by Louis Delacenserie, and comparing its size and rich ornamentation to the monumental and lavish Palais de Justice of Poelaert.

Abundance, Splendor, and Embellishment in Antwerp

Synchronizing with the inauguration of the capitol’s Arch of Triumph, Leopold traveled to Antwerp in 1905 to christen a structure in which he was directly involved as consultant to the architect and as financier: the colossal new Antwerp Train Station. The dramatic population growth and the surge of activity at the port of call for traffic from the Congo Free State meant that “tentacular” Antwerp needed new infrastructures for railway transport.13 Between 1895 and 1898, engineer Clement Van Bogaert replaced Antwerp’s existing wooden train sheds with soaring iron girders and glass vaulting that gave space to ten platform tracks (605-feet long by forty-four-feet high). Just after it was completed, in 1899, construction began again, this time to attach a gigantic station entry structure whose scale and opulence outdid the European “railway cathedral” prototype of the period. Leopold personally directed the architect Louis Delacenserie to replace the initial and more modest plans prepared by the city architect, Ernest Diltjens; the municipal council acceded to the change.14

Two ornate neo-Baroque towers and a soaring central dome fronted the station when it was completed in 1905. Twenty different kinds of marble from quarries across Belgium were incorporated into the imposing staircase and polished patterned floor of the palatial edifice. The massive, lavish, two-storied interior included waiting rooms, first class and second. Profuse gilded ornamentation equally and conspicuously crusted over both: mirrors, windows, clocks, and escutcheons cascaded with golden swirls of ribbon work and foliage. King Leopold’s personal initial, “L II,” which was disallowed on the Brussels arch, was displayed prominently at the palatial Antwerp train station, and with an uninhibited gilded flair that marked all surfaces. A spectacular dome set skyward at 245 feet topped the center of the building and was modeled on the Roman Pantheon, according to Delacenserie. The colossal scale of the building dominated the area around it, and was starkly incommensurate with the existing neighborhoods and architecture. Its heavy stone and marble materiality, size, and domed upsweep shaped what contemporaries called the new station’s “crushing” (“écrasante”) quality. They noted that “the humble traveler” was here “physically overwhelmed” and “reduced to miniscule proportions.”15

In the first phase of his reign, Leopold had been both jealous of and displeased by the 1883 Palace of Justice, the crushing “Cyclops” of Brussels that permanently marked the capitol with its lofty dome and headquartered its fin-de-siècle literati-lawyer avant-garde. Like Delacenserie decades later, the Palace’s architect Joseph Poelaert had also modeled the “empyrean heights” of its 340-foot-high central dome on the Pantheon.16 The building permanently stood out from its surrounding cityscape due to its size, scale, and imposing marble pillars. A commonplace of the period was how the Palais dwarfed the visitor. In 1905, commentators noted the obvious relation between the Law Courts and the new Antwerp train station, with one pointing out that the extraordinarily “sumptuous [station’s] … enormous proportions and excessive richness of ornamentation resembled the famous and much discussed Brussels Palais de Justice.”17 With his Congo State and investments, Leopold as Roi Bâtisseur brought the qualities of the Poelaert palace to Antwerp, not as a center of government and laws, but as a thoroughfare of imperial splendor and the networks of modern transport indispensable to generating it.

As with the organization and administration of the “Free” State, in Antwerp Leopold had to share top billing with others. If the front of the station, street side, led to marble flooring, exquisite staircases, and waiting rooms festooned with Leopold’s gilded insignia, the other side—the entry into the station for travelers arriving by train and moving from platform to city—was quite different. A large-scale stone and marble-pillared façade stretched across the iron and glass hall, with three focal points for the eyes as the traveler approached the doorway: a clock, a central relief with the refurbished city seal, and a gilded sign with the name “Antwerpen.”

Exit from the train platform into the city. Antwerp coat of arms comprised of triton and cornucopia from sixteenth-century allegory of Antwerp with the giant Antigoon’s castle on red ground and severed hands. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The seal took the form of the Antwerp coat of arms that had been reclaimed and reinvented after 1887: a grey castle resting on a red ceramic background, topped by a pair of severed hands, one on each side. This was concordant with the reclamation and reinvention of the city’s mythological founding hero, Brabo—who, according to legend, killed the giant Antigoon and threw his severed hand into the Scheldt river. Brabo and his liberation of Antwerp were represented in 1887 by artist Jef Lambeaux in a monumental bronze fountain sculpture erected in front of the town hall.18

Jef Lambeaux, Fountain Sculpture in front of Antwerp Town Hall of Brabo after killing the giant Druon Antigoon poised to throw the giant’s severed hand into the Scheldt River, 1887. Photo: Right: Wikimedia Commons.

At the train station entrance, gilded shell-like scrolls framed the red shield bearing the castle and the severed hands, all nested on a pair of golden horns of plenty. Nearby was a gilded trident, an emblem of unlocking the treasures of the seas. In the sixteenth century “Golden Age” of Antwerp, visual allegories abounded of the river god Scaldis offering up the prizes of the waters to “Antwerpia,” a female figure wearing the castle of the city as her crown. In the new golden age of wealth from the Congo Free State in Antwerp, it was not a river god but a killer of giants from whom the bounty of the seas issued. Triton, cornucopias, a castle, and severed hands: for the traveler to the colossal new station, the train-side entry heralded that this was Brabo’s country.

Antwerp Train Station hall. Source unknown.

Moving from the train platform out toward the city, the traveler filed by sweeping rows of iron beams vaulting upward toward the massive glass span. Now colored in red, the structural iron parts designed by engineer Van Bogaerts had an unusual and arresting feature: dense rows of raised circular studs—red rivets, close to one million of them—covered their surfaces in linear patterns. The running tacks animated the iron like a beaded curtain; the traveler here encountered a kind of wrought-iron pointillism. This luxuriant use of rivets marked a departure from industrial technics, in which rivets were typically deployed with restraint, fit for a purpose. In Antwerp, however, the station rivets cascaded over the iron parts, forming decorative embellishments. The geometric patterns of dots and circles protruding from the iron structures departed from any precedent in railway architecture, instead resembling designs fusing structure and skin in the Congolese ornamental body arts of tatouages, which were well known in Belgium at the time.

The profusion of rivets carried with it a final irony. The same year that Van Bogaerts completed his train station hall (1899), Joseph Conrad published Heart of Darkness, in which he reimagined his time in 1890 as a Congo Free State steamer captain hired by a Belgian company. The pivot of the narrative turns on the main character, Marlow, arriving to find his assigned steamer split apart and run aground, and his subsequent protracted and endless wait for the rivets needed to repair it. The scarcity of the rivets and the motif of the damaged steamship—tossed mercilessly as a “tin pot” on the mighty Congo River—captured Conrad’s theme of the underside of technological hubris in the scramble for Africa. Meanwhile, in 1899 Antwerp, rivets proliferated uninhibitedly in the Bogaerts station. Marlow’s fixation on the rivet, so desolatingly scarce in the Congo, contrasted with Antwerp’s supply of rivets galore, raised as if embossed on the iron beams of the splendid railway architecture.

The “Roi des Belges” steamer ship in 1889, which was piloted by Joseph Conrad on the Congo River in 1890. Source: Alexandre Delcommune, Vingt années de vie africaine: récits de voyages, d’aventures et d’explorations au Congo Belge, 1873-1894, Vol. 1 (Brussels, 1922), 286.

Both street side and train side, then—the size, scale, and materials composing the 1905 station structure maximized plenitude and extravagance. These qualities fulfilled King Leopold’s consistent aim to “embellish” his nation with buildings of grand scale and luster. But they also expressed the sudden and astonishing prosperity created for Antwerp as entrepôt of products from the Congo Free State. By 1892, Antwerp was not only the port of call for trade but also the headquarters of the most profitable of an interlinking set of banks and Congo investment companies to which the king had granted monopoly concessions in the rubber rich areas of the Free State. As Antwerp in the 1890s became once again the “Queen of the Scheldt,” the city was also the home of what was referred to as the “Queen of Congo companies.”19

This was the ABIR, or Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company, founded in 1892 with funds from British businessman “Colonel” John Thomas North, but which had been transferred entirely into Belgian hands in 1898, and was administered in Antwerp. Other companies that proliferated nearby were the Société Anversoise du Commerce du Congo and the Comptoir Commercial Congolais. The presidents and managers of these enterprises tended to draw on the same small cast of characters, especially “the king’s banker,” Alexandre de Browne de Tiège, himself also president of the new Société Générale Africaine, and Alexis Mols, Antwerp industrialist. Mols was a prominent figure in ABIR, the Anversoise, and the Comptoir.

E. D. Morel and historian Robert Harms have traced the soaring and spectacular dividends yielded by these companies’ investments in the Congo in a short and concentrated time. ABIR’s profits in the first two years (1892–1894) were recorded at 131,340 francs; by 1898, profits “had increased almost twentyfold.” Net profits for ABIR were “1,247,455 francs in 1897; 2,482,697 in 1898; and 2,692,063 in 1899.” In four years, ABIR’s profits amounted to “nearly nine times as much as its total capital.” In June 1899 “the shares stood at 17,900 francs per share, and the total value on the Antwerp Stock Exchange of this concern, whose capital is one million, was 35,800,000 francs.” Dividends paid out to ABIR investors typically doubled the price of shares, skyrocketing up until 1900.20

Postcard of the Ostend Casino, built 1878, n.d.

Opulence, Tourism, and Spectacle in Ostend

Set on the seaside coast, Belgium’s Ostend was the third imperial cityscape to be remade by King Leopold II and his business associates with the flood of Congo monies after 1895. By 1905, while Brussels and Antwerp had erupted with monuments and construction projects, Ostend had emerged as a new hub of architectural grandeur, real estate speculation, and luxury tourism, all made possible by an infusion of funds from Congo profits. Like the dramatic changes in the two other cities, Ostend’s transformation was concentrated between 1899 and 1905, following the economic surge propelled by the king’s African enterprise and his interest in directing the surplus to the built environment. As an outpost of progress, Ostend encompassed a boomtown not of harbor and trade, like Antwerp, but of beachfront and leisure, all facilitated by state-of-the-art modern transport and infrastructures.

King Leopold I had been drawn to Ostend as a favorite vacation spot, and during his reign the sleepy fishing village began to develop as a “British-style” seaside resort. In 1838, the king created a Brussels to Ostend railway connection, and in 1846 a ferry line to and from Dover was added. Attractions such as a casino in 1857 and a new public garden in 1860 brought new facilities to the town for visitors and residents alike.21 But it was Leopold II who catapulted Ostend into a splendid center of international tourism and a magnet for global capital. Said to spend “as much time in Ostend as he did in Brussels,” Leopold II brought his unwavering ambitions for urban redevelopment and monumentality to “his favorite place of residence.” In Ostend he pursued these ambitions in two phases, one before and one during and after the Congo Free State. In Ostend, Congo profits not only allowed the Roi Bâtisseur to fulfill his drive to construct enormous buildings; he also allied directly with Congo company partners to claim and develop the coastal shoreline, a hefty open area of unoccupied and lucrative terrain.

Like Antwerp, Ostend underwent a dramatic population expansion in a short period, tripling its inhabitants from 1870–1900. Municipal councils took the lead in augmenting the housing supply, as well as in creating a modern infrastructure for efficient tourist transport. Networks of steamers, trams, and railway lines coordinated to bring seasonal visitors in, and hotels and paved walkways were completed.22 As Leopold cajoled and cooperated with city officials through the 1880s to maximize upgrades and embellishments, he gained the ear of one prominent citizen of Ostend: Auguste Beernaert, who became the country’s prime minister for ten years (1884–1894). Key attractions added to Ostend were a large-scale concert hall in 1875, which joined the casino as a vast entertainment complex hugging the beach, and Leopold’s favorite spot, the 1883 state-of-the-art racetracks, the Wellington Hippodrome. Referred to with an eye-wink as “the king incognito” (generating an entire genre of photography), visitors to the seaside could often see Leopold in his top hat and summer suit walking on the sandy beach, riding his customized three-wheeled bicycle along the shore, and sitting on the seawall steps mingling with the crowds. By 1900, Ostend’s expansion and enhancement made it known as “the Queen of the Belgian seaside resorts” and “the most fashionable bathing station in all Europe.”23 Opulence, convenience, and spectacle brought the Shah of Persia, American tycoons, European aristocrats, and Belgian elites, among others, to Ostend.

Leopold’s interventions and the Congo Free State personnel and proceeds played three pivotal and understudied roles in this transformation, all of which involved ABIR. First, it was at Ostend that an early and decisive action was taken to structure the “red rubber” regime and set it in motion. In 1892, jurists such as Edmond Picard had ruled, contravening free trade laws, that the king was entitled to claim the Congo as his domanial property and thereby require taxes on labor and products. Leopold and Van Eetvelde devised one part of that royal domain as a zone for private company concessions, offering exclusive rights to extract and export wild rubber. Soon after, in 1892, King Leopold happened to meet the British “Colonel” John Thomas North at the Ostend Hippodrome. North, a Leeds-born mechanic who moved to Chile and had once worked “as a boiler riveter in Huasco,” had made a fortune speculating on Chilean nitrates in the 1880s. He owned monopoly shares in nitrate mines and quickly expanded to acquire monopolies in Chilean freight railways, water supplies, and iron and coal mines. By 1890 North was a high-society socialite worth millions and a friend of the Prince of Wales. An avid owner of thoroughbreds with a keen interest in horse racing, Ostend’s racetrack was a prime venue for him and his steeds.

The fortuitous meeting of Leopold and North brought the king in contact with a skilled entrepreneur and hard-fisted monopolist experienced in remote, resource-rich, and unregulated areas of the world. As Robert Harms discovered, Leopold approached North at the Ostend racecourse to provide the initial investments to set up the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company (ABIR). North agreed, leading to an enterprise headquartered in Antwerp that yielded swift profits soon after 1892, contributing to that city’s economic and cultural boost. North’s large block of shares from his “seed” funding brought him personally enormous dividends.24

Colonel North’s enthusiasm for Ostend and his new ABIR revenues generated the second wave of transformations facilitated by Congo personnel and profits. North maneuvered nimbly and joined with King Leopold, and then Alexis Mols, an Antwerp director of ABIR, to buy up and develop beachfront properties in Ostend in large parcels. The first traces of North’s sweep were recorded in The British Architect of August 16, 1895, which announced Colonel North’s “large building scheme at Ostend” indicating he had “bought the sea front from the King’s Chalet to Mariakerle,” a long stretch of shoreline.25 Sometime later, as Liane Rainieri has documented, Mols allied with North in claiming seaside land and developing real estate properties.26 These ventures flattened the existing dunescapes, clearing them to put houses right up to the shore. The savvy king and these two key financiers of the “Queen of the Congo companies” used their new cash flow to occupy Ostend, turning it into the luxuriant “Queen of the Belgian seaside resorts” by 1905.

Postcard of Ostend’s Royal Palace Hotel, n.d.

One visible sign of Ostend’s little-known character as Congo boomtown was the Royal Palace Hotel, a lavish property next to the king’s Royal Domain, which opened in 1899. With hundreds of rooms and a broad sweep of acreage along the beachfront, the palace “occupied the largest space of any hotel in Europe.” “Walled in by a colonnade, it featured twelve full sized tennis courts” and a privacy guarantee that brought the Shah of Persia and sixty companions, among others, to stay there in the summer of 1900.27 King Leopold met American mining magnate Thomas Walsh there, and as with North, the meeting proved beneficial for his Congo enterprise: Leopold enlisted Walsh to provide assessments of some of his own Congo mining prospects.28 The hotel was part of a Compagnie Internationale des Grands Hotels, a subdivision of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits et des Grands Express Européens, founded in 1894, that began to bundle luxury tourism and dedicated railway travel, and whose major investors were King Leopold, Colonel North, and Alexis Mols.

However ravenous the king was for Ostend land deals, and however dexterous in entangling Congo money and magnates in real estate speculation, architectural grandeur remained his primary enterprise. After 1900 Leopold realized two projects that shaped the Ostend landscape, supported, as elsewhere in Belgium, by unlimited budgets flooding in from the Congo Crown Foundation. First, Leopold carved out a Royal Domain in Ostend and its adjacent area, called Raversijde, acquiring and accruing unoccupied land. Beginning in 1902, he hired a Finnish architect to design a complex of wooden turreted structures as his beachfront residences. The expansive Royal Summerhouse and Chalet sat perched on top of a seawall dike with porches and sheet glass windows looking straight out to sea. By 1904, the Royal Stables and Garden Pavilion joined the group. More monumental, and with the heft of the neoclassical style he favored, was the colossal Royal Galleries, a marble colonnade of 1,250 feet. This arcade lined the beachfront and formed a grandiose protective cover for the king as he left his chalet for the racecourse, hotel, or other venues. Modeled on the Acropolis, the lavish colonnaded corridor was built by Charles Girault, the same Parisian architect who was commissioned to construct Leopold’s Laeken palace, the Cinquentenaire Arch, and the Tervuren Palace for the Royal Congo Museum. King Leopold’s Congo treasury made Girault the busiest architect in Europe, with crews working twenty-four-hour shifts, on unlimited budgets, and with accelerated completion schedules. By 1908, all of these titanic structures were completed.

Freddy Tsimba, Ombres (Shadows), 2016. Courtesy collection RMCA © RMCA, Tervuren. Photo: Jo Van de Vijver.

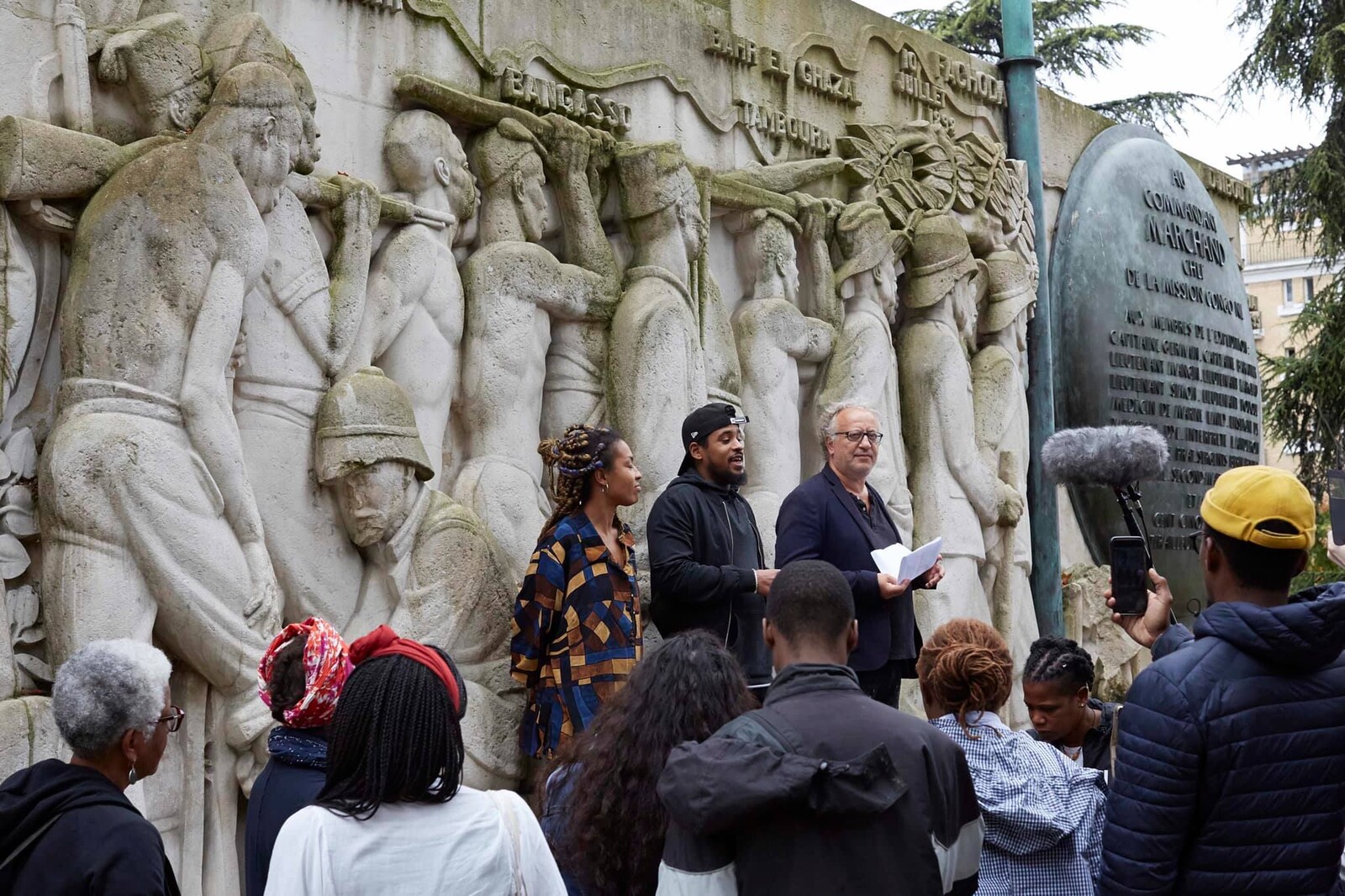

Part II: Wreckage, Reckoning, Regeneration in Twenty-First Century Contemporary Art

Taking stock of the Leopoldian empire of architecture remains a vital task for decolonizing public space in Belgium. These fin-de-siècle monumental buildings concentrate within them unexamined layers of economic, political, and social history that need excavating, from the financial arrangements of banks and the consortia of Congo Free State investment companies allied with the king, to the activities of the urban planners and municipal councils that facilitated the unprecedented number and accelerated pace of construction projects.29 This historical work, the imperative to assemble disregarded evidence of the imperial past, coexists with another initiative in full force and across multiple centers: the current work of contemporary artists to chip away at the foundations of King Leopold’s spatial occupation of Belgium.

The official institution of colonial denial, originally built to glorify King Leopold’s Congo empire—Charles Girault’s massive Tervuren palace—recently reopened as the Royal Museum for Central Africa in 2018, after a five-year renovation.30 Flemish Heritage policies protected the Girault structure from any modification. In the 1910 “Hall of Memory,” for example, it has been long noted that the walls honored and listed by name 1,508 Belgian “pioneers” who gave their lives in the Congo Free State. Congolese persons, who died en masse during the Leopoldian regime, are entirely missing. However, the new museum includes a startling intervention by artist Freddy Tsimba of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), called Ombres (Shadows). Tsimba created an inventive artwork using the medium of light to alter the space within the prescribed heritage limits. He etched on a glass plate the names of seven Congolese people who were brought to Brussels in 1897 for the World’s Fair and died there. As the sun shines on the glass, set opposite the gallery, their names appear, projected on the “pioneers” walls as legible reflections. They form temporary imprints of specific, individual Congolese people, cast as shadows on the Belgians’ hubristic commemoration.

Similarly, Aimé Mpane and Jean Pierre Müller nimbly disrupt the protected grandiosity of the entry rotunda to the Royal Museum, which bears a series of gilded allegorical statues in elevated niches around the vast hall. Set aloft by 1922, these statues celebrate Belgium “Bringing Civilization,” “Security,” and liberation to Congo and have long chafed as egregious forms of “colonial propaganda.” They too are considered protected heritage. With their 2020 RE/STORE, Mpane and Müller created huge veils, printed with images that evoke a history long denied and suppressed in the Tervuren museum. Prints on the veils depict subjects such as militarization, the destruction of native religion, and violence in the Congo Free State and the Belgian Congo. Each veil floats, superimposed over the statues, so that visitors see the gilded allegories screened through the recovered history layered over them.31

ayoh kré Duchâtelet, Ornaments and Crimes, 2023, featuring Charles Van der Stappen, Mysterious Sphinx, 1897. Courtesy of the artist and CIVA.

The 2023 CIVA exhibition, Style Congo, Heritage and Heresy, curated by Sammy Baloji, Silvia Franceschini, Nikolaus Hirsch, and Estelle Lecaille, responds to the representation of Congo and the Congolese in world’s fairs from 1885 to 1958. For the show, ayoh kré Duchâtelet created a collage that centers a prize object from 1897, Charles Van der Stappen’s Mysterious Sphinx, or The Secret, one of eighty “chryselephantine” sculptures featured in the Hall of Honor at the Brussels/Tervuren World’s Fair that year. Van der Stappen’s Sphinx is an armored female warrior accompanied by a rampant serpent and a ferocious bird. She lifts her fingers to her lips, beckoning for silence. The Sphinx’s secret is two-fold: first, her figure is assembled from multiple pieces of three separate elephant tusks, the component parts secured by the silver armor like a body cast: she is an imperial warrior with a wounded body. Second, her invitation to silence had already failed: by 1897, news of atrocities and cruelty in the Congo Free State had reached the national and international press.32

Nonetheless, the 1897 exhibition hailed the chryselephantines as masterpieces of a new Belgian patrimoine. These objects remain displayed splendidly throughout Belgium today, extending their vaunted pedigree.33 Duchâtelet’s arresting collage dramatizes in visual form the exposure of the Mysterious Sphinx’s dual secret. He slices open the side of the figure, where pieces of the ivory tusk body have been scooped out, leaving only a thin, floating silver foil. The wrecked figure collides with the reality actively denied: Duchâtelet brings to the fore an 1889 concession map of the Congo Free State. With its bright red markings, the map melds with the sphinx’s face. Positioned at her fingers, it appears that the ivory sphinx is eliciting silence and complicity with the Congo map and the “red rubber” regime that was already recognized at the time.

In Chrystel Mukeba’s series of portraits, “Living Traces,” Belgians of Congolese descent are photographed in Art Nouveau houses by Victor Horta. Two of Mukeba’s photographs are situated in Horta’s famous 1897 mansion for Edmond Van Eetvelde, the Secretary of State of the Congo Free State. The closest ally of King Leopold II, Van Eetvelde devised and enforced the key policies administered in the Congo as a site of extraction: forced labor, corporal punishment, and the legal entitlement of “terres vacantes,” which defined all Congo Free State territories as unoccupied, vacant lands and hence the private property of the king. Horta’s pioneering structure, with its hollowed-out interior iron and glass octagonal court, is celebrated as a pinnacle of modernist technological innovation. But the house was also a stage set for Belgian imperial exploration and domination, designed to host receptions for investors in Congo railways and product companies. Seen in this light, Horta’s coup de fouet (“whiplash”) style looks very different: the cavernous interior court of the Van Eetvelde house offers less a visionary prefiguration, as Sigfried Giedion termed it, of the Corbusian plan libre (open plan), than an architectural embodiment of terres vacantes. The propulsive iron columns surrounding the space, rampant and twisting, not only evoke the wild, aerial rubber vines of Congolese forests, but also the tools required to extract their latex “liquid gold”: the long flogging whip of the chicotte, a punishment Van Eetvelde explicitly defended from his Brussels office.34

Mukeba returns living Belgians to the house where economic voracity shaped an imperial regime and whose administrator-resident decreed that the Congo Free State was a vacant property, divested of people and history. In one portrait, a seated woman wears a long dress of African cloth animated by designs similar to the abstracted floral forms of the Horta wallpaper and the curving metal stands behind her. Gazing straight out to meet viewers’ eyes, her grounded, steadfast, and vibrant pose confronts the imperial past in one of its central monuments. The Belgians of Congolese descent in Mukeba’s portraits firmly inhabit Horta’s spaces. They repel the legacy of terres vacantes in the architecture that materialized it, making them anew as “terres occupées.”

Daniela Ortiz, The Rebellion of the Roots (Belgium), 2021. © Daniela Ortiz / Kadist Collection Paris. Courtesy of the artist and CIVA.

Daniela Ortiz, The Rebellion of the Roots (Belgium), 2021. © Daniela Ortiz / Kadist Collection Paris. Courtesy of the artist and CIVA.

Daniela Ortiz, The Rebellion of the Roots (Belgium), 2021. © Daniela Ortiz / Kadist Collection Paris. Courtesy of the artist and CIVA.

Daniela Ortiz, The Rebellion of the Roots (Belgium), 2021. © Daniela Ortiz / Kadist Collection Paris. Courtesy of the artist and CIVA.

Daniela Ortiz, The Rebellion of the Roots (Belgium), 2021. © Daniela Ortiz / Kadist Collection Paris. Courtesy of the artist and CIVA.

In Daniela Ortiz’s The Rebellion of the Roots (Belgium) (2021), a sequence of small acrylic paintings on wood depicts tropical plants as both subjects and agents. Ortiz represents the plants as kidnapped and “held hostage” in European greenhouses, while also growing strong in new ways. Adapting the whimsy and simplicity of folk art, one panel shows the “Royal Greenhouse Laeken” with cartoonish figures wielding the chicotte as they prance on top of the glass domes. Nearby and outside the enclosure, a Congolese plant flourishes as it is fed by soil filled with Congolese skeletons, reminiscent of the illustration of “The Congo Free Graveyard” in Mark Twain’s pamphlet King Leopold’s Soliloquy. In another, the remains of Patrice Lumumba, with his signature eyeglasses, are shown underground feeding a robust native plant, which towers over a group of female figures and a caption beneath reads: “Nourished by the spirit of Patrice Lumumba, ntundulu fruits will grow big and tasty for Congolese mothers to nurture her bodies.”

Ortiz’s depiction of nourishing fruit offers a stinging retort to the way botanical specimens were considered by administrators of the Congo Free State. During the 1880s, for example, as explorers discovered the wild rubber vines lining the Congolese forests, they ridiculed the natives for snacking on their orange fruits while ignoring the latex thrumming through each and every liana, what they called “vegetable boas with veins of gold.”35 A subsequent panel shows how Congolese women’s bodies give birth to “babies in the colonizer lands.” These babies will grow strong from ntundulu plants, “tear down monuments” of “colonial perpetuation,” and begin “reparation.” Above this caption, Ortiz shows a statue of King Leopold II toppled by three young Afro-Belgians, one of whom hoists a huge white tooth above his head, like a trophy. Ortiz draws on the format of ex-votos, a genre of populist religious art expressing gratitude for acts of divine intervention in earthly ordeals. A number of paintings in her series explicitly declare thanks: not to a supernatural intercessor, but to her subjects, the colonial plants. In one, a tiny woman sits and sprinkles leaves at the edge of a giant cup of tea, underneath which reads: “Thank you strong anticolonial roots of the rooibos that grow to find the end to Belgian violent greed.”

Independent from the CIVA exhibition, Sammy Baloji’s 2022 sculpture The Long Hand suggests ways that contemporary artists continue to wrestle with the colonial past while generating innovative possibilities for moving forward. In The Long Hand, Baloji mobilizes evocative forms to recover repressed histories and to activate new narratives in the present, balancing the ethics of memory with the responsibility to tell new and multiple stories. The sculpture was the result of a commission by the Antwerp Public Art Collection and Middelheim Museum for a permanent work in public space, the first time an artist of Congolese descent was invited to do so. Baloji created a monumental sculpture and stationed it on the shores of the Scheldt River. Set like a sentinel along the quay with its back to the waterway, the large bronze figure is raised and surrounded by an open brick platform with steps leading up toward it.

The name and shape of Baloji’s sculpture are derived from the lukasa, a cultural device used by the Luba people of southern Congo to transmit history and mythology by “a so-called man of memory.”36 Lukasa, meaning “the long hand” in Kiluba, are memory boards made of wood, decorated with abstract carvings and inlaid with stones, shells, beads, or pieces of metal. “The long hand” refers to both the object and the subject who operates it. Archival photographs show how a “man of memory” sits with his arms extended, holding the lukasa in one hand, the other moving across and along the box, with raised carvings and varied ornaments acting as prompts for oral histories and stories. The lukasa is thus a physical mnemonic device and an agent of Congolese communal life ignited by the man of memory, who releases its collective power.

Baloji’s sculpture is a monumental lukasa, an allusive Luba form in Antwerp public space. On the figure’s bronze surface, Baloji creates his variant of the traditional lukasa’s protrusive tracers and mnemonic prompts: he inlays large colored plastic knobs in the shape of diamonds, setting them in the pattern of the sea route between the ports of Antwerp and Muanda. These shapes and this mapping call to mind memories of extraction and of the cargo ships that launched from Antwerp to haul back Congo’s resources and raw materials during the imperial and colonial periods. Beyond the past, however, Baloji’s The Long Hand is resolutely focused on the present and future. In joining the statue to the brick platform, Baloji aims to provide spaces “to sit, to recall, to remember, and to remember differently.”37 The particular site and setting offers possibilities for what he imagines as chance meetings and for relational encounters “beyond absolutes”; a living negotiation of shared histories.

The materiality of The Long Hand deepens the artist’s goals of commemoration and regeneration. Bronze, bricks, and recycled plastic, “three composite materials,” form the monument. The main body of the sculpture is bronze, “an alloy of tin and copper,” which derives from the mines of the DRC. For the adjoining platform, bricks from Masseik, Limburg, are used, which are made from the spoil tips and mining debris of “Belgium’s lost mining industry.”38 The colored knobs recast plastic construction waste into bulky diamonds. Drawing from sites of abandoned mines, Baloji melds the shared history of capitalism’s discarded industrial labor and despoiled nature in both Congo and Belgium. In his earlier photographic work, Baloji had created stark images of the mineral mines near Lubumbashi, superimposing images of colonial-era exploited labor onto contemporary locations, now desolate places of decay and ruin. In The Long Hand, he uses the raw materials and remnants of closed mines and construction debris—of the colony as well as the colonizer—for his artwork, molded from the ground up. Copper, tin, clay, soil, spoil tips, and plastic refuse are reused, creating a space for reflection, interaction, and impromptu conversations, divested of what Baloji calls the harsh closure of certainties and absolutes, and open to the flow of competing narratives and listening ears.

Pierre Braecke, Vers l’Infini, ivory and gilded bronze “chryselephantine,” 1897, with Congo wood base by Victor Horta, shown at the 1897 Tervuren Congo exhibition. Source: Collection RMAH.

The Long Hand breaks the mold of the Leopoldian empire of architecture. The core of Antwerp’s urban space and monumental structures took shape from 1885–1910 as the city surged and became the imperial port of Belgium. From the opulent colossus of the 1905 train station, the 1887 Afrikadock, and the lavishly renovated Town Hall, to the large fountain sculpture in the heart of the central square (Grote Markt), it was the Congo Free State trade, profits, and profusion that gave Antwerp its distinctive and enduring built environment. Baloji’s figural memory board stands with its back toward the riverway and faces inward, toward the city, reorienting Antwerp’s symbolic geography. At the height of Congo expansionism, fin-de-siècle Antwerp embodied an exhilarated launch point, a collective perception of release from limited horizons, and the end of Belgium’s timorous esprit casanier (“homebody syndrome”). Explorers and expeditioners set sail for Matadi after 1887 with the rallying call “Vers l’infini!” (“towards infinity!”), infused with the fantasies of limitless plenty across the seas.39 Poet Emile Verhaeren considered Antwerp a “ville tentaculaire” (“tentacular city”), and in 1895 cast the port as a giant grasping hand (“main énorme”). This hand, fingers stretched, closed over the whole world, wresting its treasures and bounty.40

Verhaeren’s representation of Antwerp as a giant hand reverberates at another level, returning to the origins and identity of the city that materialized in public culture in 1887. As mentioned earlier, the legend of Antwerp’s founder, Brabo, who killed the giant Antigoon and threw the giant’s severed hand into the sea, was reclaimed and reinvented in the late 1880s. The symbol of Brabo’s heroic feat—a giant’s severed hand—proliferated in urban spaces, cast in bronze as part of the monumental fountain by Jef Lambeaux. As Congo adventurers boarded their ships, one of the last things they saw in the distance was the soaring figure of Brabo, hoisting the giant’s hand as he propelled it toward the sea. The sculpture dominates the city square fronting the Town Hall, and embodies one story for the name of the city—the throwing of the hand (“handwerpen” in Dutch).

The mythic ancestor Brabo bore provocative salience for the grisly specificity of Belgian imperial violence in the Congo Free State—the practice of hand severing, in which native soldiers were required to bring their officers a hand for every villager they shot for resisting rubber collecting, as proof they had not wasted bullets hunting or firing their rifles at random. The Lambeaux statue’s rise predated public knowledge of this brutality, but within a few years revelations of the dismemberments began to circulate in the press and Parliament. Deputy Georges Lorand’s 1896 front page article in La Réforme, “Mains coupées” (“Severed Hands”), set off a decade of controversy, called Belgium’s Dreyfus Affair. Refurbished emblems of the city and a giant bronze severed hand dominated Antwerp as shocking photographs of Congolese natives with handless stumps created national and international uproar. Some contemporaries made the connection.41

Nonetheless, for more than a century, any link between Antwerp’s civic legend and the iconic atrocity of the rubber regime in the Congo Free State remained a glaring blind spot, hiding in plain sight. Today, children clamber on the dismembered trunk of the giant’s body that Lambeaux splayed around the base of the fountain; chocolate Antwerpse Handjes (“little Antwerp hands,” severed-hand chocolates and cookies), remain a favorite souvenir for visitors.42

Sammy Baloji’s bronze The Long Hand operates within this particular force field of Antwerp’s visual culture. Indeed, his sculpture offers a powerful counter-monument to Brabo and the severed hand as a defining artwork for the city. Along the Scheldt shoreline, Baloji creates a sentinel of Congolese vitality. His lukasa, an evocative form of a memory board and a memory man, provides a dramatic riposte to Lambeaux and his Brabo. Brabo, too, is a man of memory—his myth links freedom with victory over hostile forces, achieved by unleashing violence and retaliatory punishment. In his triumph, as Lambeaux’s sculpture renders in unusually graphic form, Brabo has hacked up his enemy’s body and hoists the giant’s hand skyward, poised to hurl it into the sea. But in Baloji’s rendering, we encounter elements of the Luba “man of memory” as generative sparks for a new Antwerp. As he activates the mnemonic device, the man of memory cradles the wooden board with one arm and holds it steady. He moves his other hand along the protrusive surface, igniting stories, histories, and memories as binding forces among those gathered to hear him. For Baloji, the compositional melding of brick, bronze, and plastic, and the themes they embody—mapping ocean journeys for extraction, labor and natural resources wasted and reused, chance encounters and conversations stimulated—suggest a possibility for exchange, for a Congo in Belgium. Not the portside propulsion “vers l’infini,” but a decolonial pulse, in a grounded place: vers l’amitié (“towards friendship”).

Louis de Lichtervelde, Léopold II (Brussels, 1926), 213-227. The unusual character of this imperial structure—which studiously avoided the word “colony”—needs re-emphasizing.

I examine this Belgian modern style in other publications and in my forthcoming book. See, for example, “Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness, African Lineages of Belgian Modernism,” Parts I, II,II, West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture (2011-2013); “‘Modernité sans frontières’: Culture, Politics, and the Boundaries of the Avant-Garde in King Leopold’s Belgium, 1885-1910,” American Imago 68, no.4, (Winter 2012): 707-797; “Henry Van de Velde: Art Nouveau as Style Congo, 1895-97,” in Style Congo: Heritage and Heresy, ed. Sammy Baloji et al.. (Brussels: CIVA/Leipzig, 2023), 7-16; and “‘Percer les Ténèbres’: Traces of the Congo in Victor Horta’s Art Nouveau,” in Horta and the Grammar of Art Nouveau, eds. Iwan Strauwen and Benjamin Zurstrassen (Brussels: Mercatorfonds & Bozar Books, 2023), 131-141.

In 1895 Emile Verhaeren published a book of poems celebrating Belgium’s industrial power, Les villes tentaculaires. “Tentacular capitalism” is my play on, and extension of, Verhaeren’s invocation of tentacularism as the only apt way to characterize Belgium’s industrial and financial might. See Debora Silverman, “Boundaries: Bourgeois Belgium and ‘Tentacular Modernism,’” Modern Intellectual History, 15, no. 1 (2018): 261–284.

On Rogier and the king’s ambitions as urbanist, see Lichtervelde, Léopold II, 43-60; Colonel B. E. M. G. Stinglhamber and Paul Dresse, Léopold II au travail (Brussels, 1945), 221-259.

Speeches of 1857-1862, cited in Lichtervelde, Léopold II, 48-51; Stinglhamber and Dresse, Léopold II au travail, 222-223. He used the terms “étonne”, “l’assaut,” “frappe”—terms of physical force and sneak attack, not by military means but by streetscape capture.

Silverman, “Modernité sans frontières,” 714-720.

Léon Daudet, cited in Stinglhamber and Dresse, Léopold II au travail, 240. On Leopold’s architectural expansionism in 1905, see Liane Rainieri, “Léopold II: Ses conceptions urbanistiques, ses constructions monumentales,” in La dynastie et la culture en Belgique, ed. Herman Balthazar and Jean Stengers (Brussels, 1990), 173–92; Rainieri, Léopold II urbaniste (Brussels, 1973); Georges-Henri Dumont, La vie quotidienne en Belgique sous le règne de Léopold II, 1865–1909 (Brussels, 1999), 18–28; Piet Lombaerde, Léopold II, roi-bâtisseur (Ostend/Ghent, 1995), 88-91; Charles Girault, “L’Oeuvre architecturale de Léopold II,” L’Émulation 11 (1926): 137-147. On tracking the Congo revenues in the Fondation de la Couronne that funded monumental national architecture and private real-estate ventures in 1905, see A. J. Wauters, Histoire politique du Congo belge (Brussels, 1911), 248–51, where they are described as “a véritable débauche”; Félix Cattier’s itemization in Étude sur la situation de l’État indépendent du Congo (Brussels, 1906),. 219–40; Jean Stengers, Combien le Congo a-t-il côuté à la Belgique? (Brussels, 1957), 150–51, 144–294; Neal Ascherson, The King Incorporated: Leopold the Second and the Congo (London, 1963, New York, Granta Books, 2001)), 273–78; and Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (New York: Houghton Mifflin Reprint, 1999), 165–70, 255–59.

Architects’ drawings for vast reception halls are included in Rainieri, “Léopold II,” and Lombaerde, Léopold II. On the greenhouses see Irene Smets, The Royal Greenhouses, Laeken (Ghent, 2001). These enormous structures are open to the public once a year in May. On the Japanese and Chinese pavilions purchased at the Paris 1900 exhibition and reassembled on site, see Thierry Demey, Le domaine royal de Laeken (Brussels, 2005); and Chantal Kozyreff, La tour japonaise de Laeken (Brussels, 1989).

On the Rue Brederode Congo company offices and personnel, see Debora Silverman, “Gold Rush, Congo Style: Gustav Klimt’s ‘Expectation and Fulfillment’ in the Palais Stoclet,” in Erasures and Eradications in Modern Viennese Art, Architecture and Design, eds. Megan Brandow-Faller and Laura Morowitz (New York and London: Routledge, 2023),173-185; Colette Braeckman, Jean-Francois Munster, and Oliver Mouton, “Les traces du Congo demeurent à Bruxelles,” Le Soir, April 28, 2010, ➝.

This incident, an open secret and delicious victory for Leopold at the time of the arch’s inauguration, is recounted in Cattier, Étude sur la situation, 240–41; see also Stengers, Combien le Congo a-t-il côuté?, 194–99; and Ascherson, King Incorporated, 275. On the structure, plans, and building of the new gargantuan arch, see Rainieri, “Léopold II,” and Rainieri, Léopold II urbaniste; the latter includes a rare photograph of the 1880 incomplete arch with missing middle that was the dismembered gateway to Brussels for twenty-five years.

Wiliam Bourton and Daniel Couvreur, “Le Centenaire de l’Avenue de Tervueren (I): La Voie royale de l’Expo coloniale, La mémoire vivante de Léopold II à 80 ans,” Le Soir, May 28, 1997; M. Merlot, “Le Centenaire de L’Avenue de Tervueren (III): Les Sentinelles vertes de Léopold II, des tombes de Congolais,” Le Soir, May 30, 1997.

“Discours du Roi au Président du Sénat le 1er Janvier 1905,” in André de Robiano, Le Baron Lambermont, Sa vie et son oeuvre (Brussels, 1905) 201-202.

Verhaeren calls Antwerp “the tentacular city and port,” 1895.

This discussion and what follows are based on the informative online pamphlet and history of the station, “Welcome to Antwerp Central, Railway Cathedral of the 20th and 21st Century,” in plantlocation Europe.eu.doc

“Welcome to Antwerp Central,” and quote in postcard of the period. W. G. Sebald writes a powerful description of the massive scale of the Antwerp station and the dizzying view of the dome as travelers moved through it in his novel, Austerlitz.

Silverman, “Modernité sans frontières,” 714-720; 741-751. The term “empyrean heights” in the Poelaert Palace is that of Count Henry Carton de Wiart, one of the young literati-lawyer circles that clustered around Edmond Picard there in the 1890s.

“Welcome to Antwerp Central.”

The renovated Antwerp Town Hall added a succession of these types of seals with the castle and severed hands when it modernized between 1889 and 1902. On the revival of the symbolism, the legend of Brabo, and the 1887 statue, see Silverman, “Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness,” Part III, 26-30; and Debora Silverman, “La Main lancée, Hiding in Plain Sight,” in The Grand Rotunda in the Royal Museum for Central Africa, ed. Aimé Mpane and Jean Pierre Müller (Tervuren: MRAC & BAI, 2023), 172-178.

Edmund Dene Morel, Affairs of West Africa (London, 1902), 335.

Morel, Affairs of West Africa, 337 figures, and 335-337; Robert Harms, “The World ABIR Made: The Margina-Lopari Basin, 1885-1913,” African Economic History 12 (1983): 122-139, especially 131; Robert Harms, “The End of Red Rubber: A Reassessment,” The Journal of African History 16, no. 1 (1975): 73-88; John Tully, The Devil’s Milk: A Social History of Rubber (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2011), 403; and Robert Harms, Land of Tears: The Exploration and Exploitation of Equatorial Africa (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 361-470. Useful and revealing contemporary charts tracking the quantity of rubber exports and profits accrued between 1892 and 1897 can be found in Lieutenant Th. Masui, Guide de la Section de L’État indépendante du Congo à l’Exposition de Bruxelles-Tervueren en 1897 (Brussels, 1897), 411.

Patrick Florizoone, Les Bains à Ostende (Brussels, 1996), 17-79, ➝.

The small-scale ferries were replaced by turbine steamers, which were shown in travel posters with elegant and affluent crowds. Local fishermen’s livelihoods were threatened by this new technology, and conflict ensued. In the 1896 novel Birch Mitsu by Georges Eekhoud, for example, the writer captures the destruction of fishing by steamer traffic and tourism, and the violence of fishermens’ strikes. One such Ostend strike took place in 1887, and Eekhoud’s friend, James Ensor, made a famous, colored print representing the violence of the local militia against the popular protesters. On Ensor, Ostend, and the Congo, see Debora Silverman, “Ensor’s Panache: Army and Empire in ‘The Temptation of Saint Anthony’ and in Belgium, 1887,” ➝.

The words of a travel journalist of 1900 in Kathy Warnes, “Historical Time and Tides Ebb and Flow in Ostend, Belgium,” Windows to World History, ➝; Derke Blythe, Flemish Cities Explored: Bruges, Ghent, Antwerp, Mechelen, Leuvem & Ostend (London: Pallas Athene, 2013).

Neal Ascherson indicates that it is likely that North may even have been a “front man,” using Leopold’s monies for ABIR as well; in any case, Ascherson and others remind us that Leopold and the Crown Domain of the Congo Free State owned 50% of all ABIR shares.

The British Architect, August 16, 1895, 124.

Rainieri, Léopold II, urbaniste, 209-239. Rainieri’s research showed how the king worked in concert with North and Mols, though not enough notice has been made of this, especially regarding the sudden profusion of cash that poured in to develop Ostend from the Congo rubber companies.

Warnes, “Historical Time and Tides Ebb and Flow in Ostend.”

Warnes, “Historical Time and Tides Ebb and Flow in Ostend.”

For an examination of the later period, also with a long-hidden history, see the discussion of the financial entanglements of the Banque Lambert, Umicore, the Union Minière, and the Belgian Congo in Neil Munchi, “Belgium’s Reckoning with a Brutal History in Congo,” Financial Times, Nov. 12, 2020.

The new museum is now also known as the Africa Museum.

Aimé Mpane and Jean Pierre Müller, The Grand Rotunda of the Royal Museum for Central Africa, RE/STORE (Tervuren: MRAC & BAI, 2023).

I have written extensively about this sculpture, its violent theme and technical handling, and its relation to violence and disguise in the Congo Free State. See Silverman, “Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness,” Part I, 141-151; and Debora Silverman, “Diasporas of Art: History, The Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, and the Politics of Memory in Belgium, 1885-2014 ,” Journal of Modern History (2015), 23-34.

Silverman, “Diasporas of Art and the Politics of Memory”; Silverman, “Modernité sans frontières,” 747-751, 788-791. Just this year, the renovated Antwerp Museum of Fine Arts drew attention for the first time to the Congo Free State connections of its chryselephantine sculpture, Diana the Huntress, in a new label for its display case.

Silverman, “Art Nouveau,” Part I, 163-170; Silverman, “Horta’s Terres Vacantes and the Van Eetvelde House,” in Horta and the Grammar of Art Nouveau (Brussels, 2023), 131-141.

A. Merlon, Le Congo producteur (1888), 87, 93.

“Sammy Baloji: The Long Hand,” Middelheim Museum, ➝.

See ➝.

Ibid.

Alexandre Delcommune, Vingt années de vie africaine, 1874-1893, récits de voyages, d’aventures et d’explorations au Congo Belge, Vol. 1 (Brussels, 1922); Camille Coquilhat, Sur le Haut-Congo (Paris, 1888).

Émile Verhaeren, “Le Port” and “Et la ville comme une main, les doigts ouverts/Se refermant sur l’univers,” in Les Villes tentaculaires (1895), see ➝.

Key evidence and photographs of mains coupées appeared in books by E. D. Morel, the shipping clerk turned journalist who exposed forced labor and violence in King Leopold’s Congo, such as Affairs of West Africa (London, 1902), 324-342; King Leopold’s Rule in the Congo (London, 1904); Red Rubber: The Story of the Rubber Slave Trade Flourishing on the Congo (London, 1906); and Mark Twain, King Leopold’s Soliloquoy (Boston, 1906). See also Harms, Land of Tears, 373-389; and Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost, 164-166, 226-227. Morel is one contemporary who suggested that the Antwerp city symbol of the severed hands and the practice of severing hands in the Congo were deeply intertwined. Explanations for the uniqueness of Belgian imperial violence are incomplete and usually attributed, if at all, to Belgians’ excessive thrift and punctiliousness. I have long argued that this was not simply a pathology of accounting but part of a cultural framework Belgians brought with them. I analyze the 1887 Lambeaux statue and identify the late nineteenth century visual culture of severed hands in Antwerp, as well as the broader expressive culture of violence and dismemberment within Belgium that predates and interacts with imperialism in the Congo Free State in Silverman, “Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness,” Part III, 22-30; 50-55; Silverman, “La Main lancée,” 172-178; and Silverman, “Modernité sans frontières,” 778-791.

This blind spot has recently been brought to light: in 2020 artist Jean Pierre Müller made a large print recreating Lambeaux’s 1887 statue of Brabo throwing the giant’s hand as a floating veil in the permanent installation in the rotunda of the Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, provoking visitors to see the connection between l’expansion belge and the imperial violence of severing hands in the Congo Free State. A controversy has broken out about the ubiquity of chocolate hands in Antwerp as souvenirs, suggesting they are not whimsical evocations of a city myth and “logo,” but charged with a deeply fraught history and horror. Mayor Bart de Wever has weighed in on this debate to defend the city legend. On Müller’s Brabo at Tervuren, see Mpane and Müller, The Grand Rotunda; and Silverman, “La Main lancée,” 172-178.

Appropriations is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and CIVA Brussels within the context of its exhibition “Style Congo: Heritage & Heresy.”

Category

Subject

My thanks to Nick Axel, Nikolaus Hirsch, and Jeffrey Prager.