The term “circularity”—which will soon probably replace the exhausted and discredited word “sustainability” in architectural and construction parlance—implies a kind of supreme intentionality, where the lifecycle of a material has been pre-ordained by wise planners, long in advance of its “birth,” in a series of cute diagrams.

The reality of circularity, of course, is often messier, always much harder work, and is usually more of a downward spiral—from solidity towards aggregate—than a perfect circle. When materials from demolished buildings aren’t simply crushed on site and accounted as virtuously recycled, “circularity” begins with “salvage,” and with all the desperation, precarity, and uncertainty that word contains. The traditional salvage industry operates largely unseen, like scavengers on a demolition site. Salvage yards are typically headquartered in the suburbs or countryside, where land is cheap enough to store huge stockpiles of materials that retain some value at the component scale, but which have no guarantee of ever being bought or reused.

There is a section of the stonemasonry trade—stone restoration—that operates very differently however, as one that is dedicated to conserving heritage, repairing and reintegrating building components, and rehabilitating facades. Like the traditional salvage industry, it is concerned with reuse and it long predates the policy-driven concept of circularity. But crucially, it offers lessons that might build a bridge to a more widespread salvage practice that engages—and enlarges—traditional, more pragmatic salvage operations. Much can be learned from stone restoration in terms of systematic dismantling, storing, repairing, and reassembly.

Part I: Remove and Rebuild

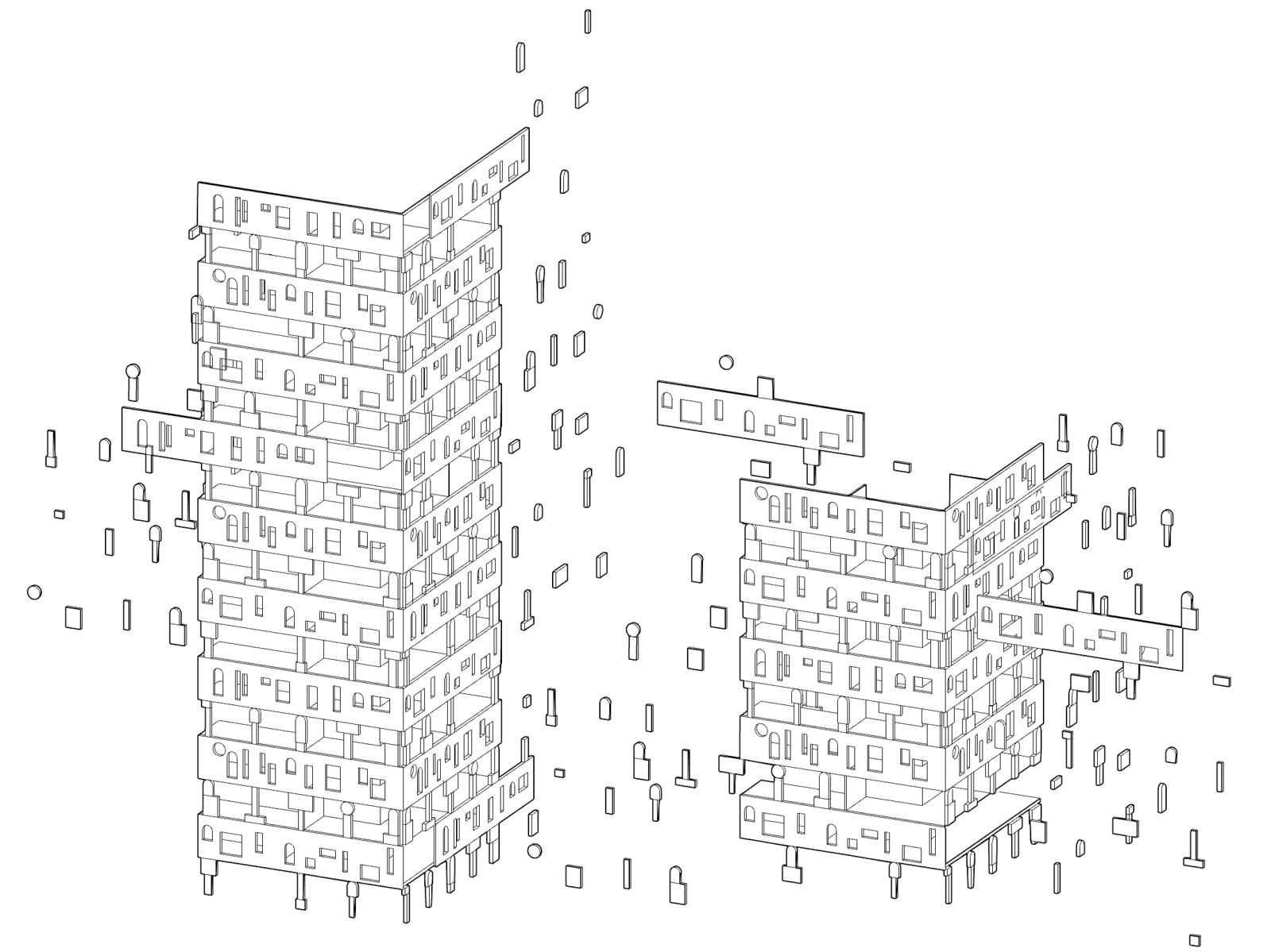

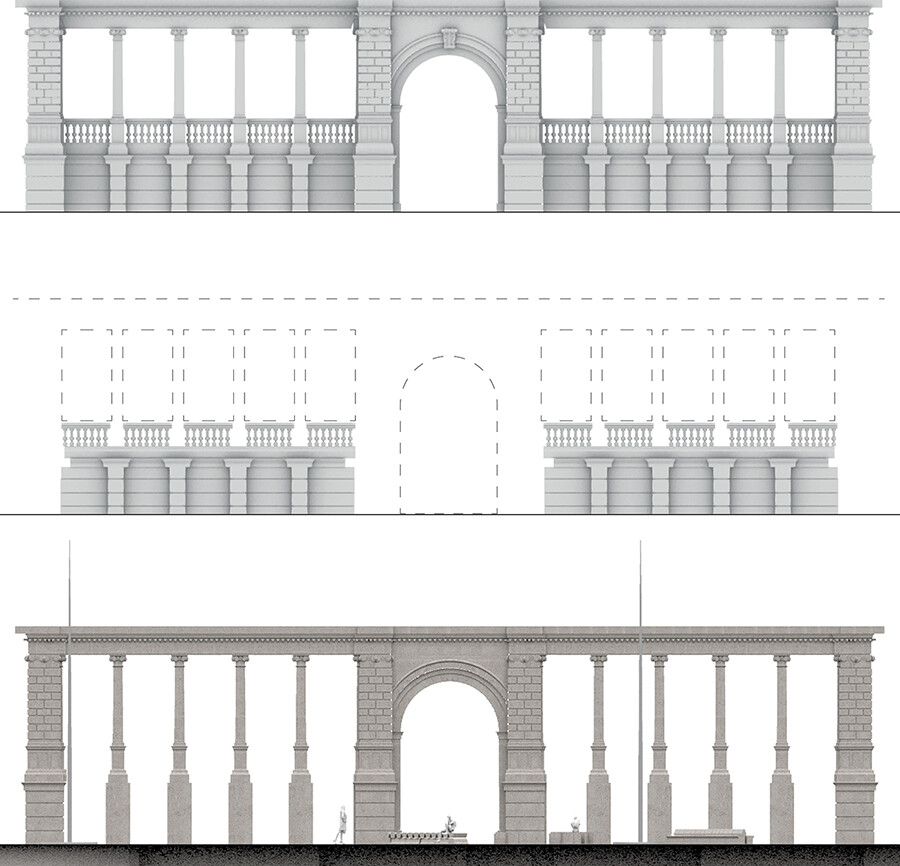

Robert Rees, site manager for UK-based stone contractor Paye, is an expert in anastylosis, or the art of reassembling a facade in its original state.1 Rees has been site manager for several listed buildings in London, including the dismantling and selective rebuilding of the Victoria & Albert museum’s Aston Webb Screen—a thick wall made of Portland stone ashlars. The Aston Webb Screen (AWS), named after the architect who designed it (and much of the V&A), was originally built in 1909. Located at the side of the museum along Exhibition Road, the function of the AWS was to shield the V&A’s hefty boilers—located in a courtyard inaccessible to the public—from view. The AWS suffered damage during the Blitz and accrued a patina from a century of London pollution, while the V&A’s boilers were put out of service decades ago. Since then, maximum accessibility became an imperative for museums, and the V&A had a courtyard it wasn’t using, as well as a potential entrance from Exhibition Road. So, in 2013, Amanda Levete Architects were commissioned to create a kind of porous colonnade out of what used to be a barrier. All 1,375 stones in the AWS—ashlars, arches, gargantuan window thresholds, oversized mullions, rusticated blocks—were measured and numbered. Four hundred and fifty selected stones were earmarked for removal to create multiple openings in the AWS. Rees managed this precision process on behalf of Paye, which began in 2015. Seven years later, Rees was also in charge of bringing some of the removed stones back to site, this time placing them in the street, opposite the screen where they once lodged.

In an interview with the authors, Rees gives a glimpse of what it takes to recirculate building components from London to Dorset, and back to Exhibition Road:

Can you describe the fundamentals of your trade?

Rob Rees: Our trade consists predominantly in taking stones down and building them back exactly as they were. That’s done by different types of stonemasons. We have what we call stone fixers. They do lots of the new-build work, conservation-wise. That’s a three-to-four-year course to learn, and the training is different. So your appreciation of the stone is different. Because you have to be taught by hand, you have more appreciation of what goes into it. Anyone that’s trained as banker mason, you’ve really got to want to do that, to dedicate yourself to the training. So a lot of stonemasons prefer conservation. Even though we’ll do new-build too, conservation work is really the reason we’re into this. I enjoy working with the masons around me, I enjoy the historic building sites and the restoration. A good day is when everybody turns up on time and does what they’re meant to do. We try to organize stuff to the point where we don’t have too many problems.

How did the Aston Webb Screen job work?

RR: The Aston Webb Screen (AWS) is the only Grade One listed structure where permission was given for it to be changed. That’s because Webb made two designs for the screen, so we were allowed to convert it from a continuous wall with just a singular arch into many open arches. Our job was to remove those stones to open it up.

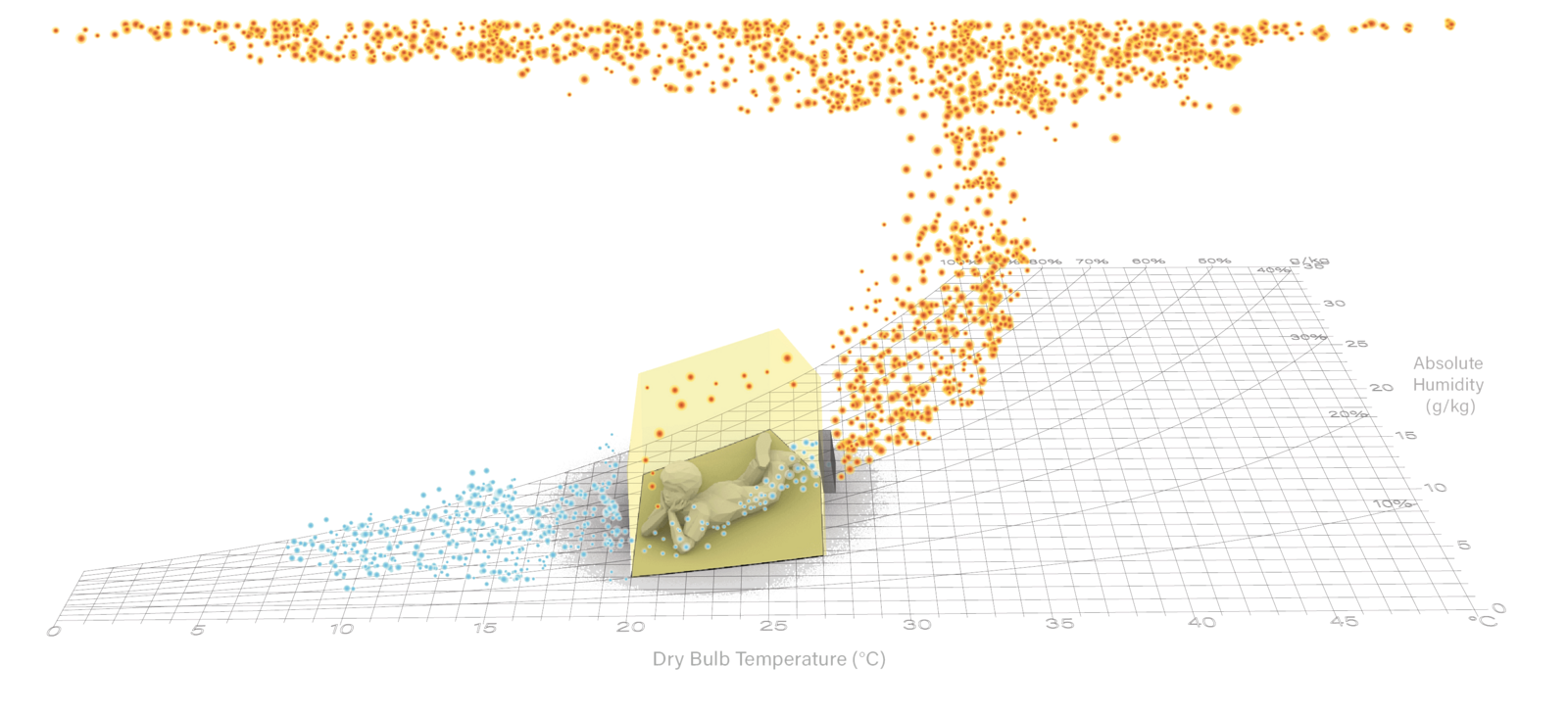

Phases of the Aston Webb Screen: original, what was removed, and what was rebuilt. Drawing: Juliet Haysom.

What were the particular challenges of working on the AWS and what techniques did you have to employ?

RR: I don’t survey the buildings. I just make sure they get back how they should be. That job was difficult with the AWS because it’s a classic Victorian build: they liked using a lot of concrete and a lot of cement and other parts. Some Victorian buildings use lime mortar, which is easier, but we found out that this one was basically built with concrete. So it was about trying to cut through that, which took much longer than we thought. In terms of machinery, we had six electric tackles to loosen the stones up. And we used different kinds of wet cutting tools. We try to use water on everything because you can’t have dust. After we managed to dismantle everything, it was challenging to clean the concrete off the stones enough for us to rebuild the AWS in its new form.

What did you find behind the ashlars?

RR: There were four buttresses. Each buttress—each course of stone—contains nearly 500 bricks hidden within. So we had to cut through thousands of bricks to get to the stone. The top section also contains thousands of bricks that you can’t see. So once you’ve taken it down, it looks nothing like what it was. Once you detach the stone, the bricks had to go. We introduced new bricks bonded with lime mortar, using the exact same sands, the exact same lime. Heritage style. So there’s a lot of effort that you can’t see inside the rebuilt AWS.

How did the rebuilding process work in terms of labor and logistics?

RR: I was managing the job. I had three stonemason pairs that built the whole job plus two bricklayers, and carpenters to design and cut the arch formwork to support the arch and lead workers as well. The new wall was mainly built by three stone fixers, stonemasons, and we also have a small team of banker masons. The original structure, with just one arch, was more robust than the rebuilt version with the multiple openings, because it was just one long wall. It’s changed quite a lot. The arches were the last things to be built. We used them to distribute the buttresses because of the sheer amount of brickwork involved. There were a lot of logistics involved with it. We were having three deliveries every day of around 4,000 bricks and about twenty pallets of stone to build the AWS on time. You just don’t see all the stuff that’s inside the wall.

Bricks and ashlars removed from the AWS. Source: PAYE.

Carefully forcing apart the ashlars. Source: PAYE.

Strenuous removal of Portland Stone ashlars from the Aston Webb Screen, 2015. Source: PAYE.

Bricks and ashlars removed from the AWS. Source: PAYE.

How accurate was the rebuilding, given all the changes that needed to happen to the screen?

RR: If you’re putting something back the way it came down, you don’t want to increase the joints. A lot of old buildings will have three-millimeter joints, or sometimes five. But by cutting the stone you can increase the width of the joint too much when you rebuild it. You could end up with double the original joint, and that kind of ruins the whole look of the listed building. Sizing was difficult—getting the columns to set out exactly in the spaces where they should be. We did a dry run by setting up all the column bases in our yards to make sure the spaces were correct for the arches.

How did you try to preserve the imperfections of the screen, its unique history?

RR: There were stones that were badly damaged by bombs in World War II. Sometimes you pick up the stone and it falls into pieces. So you have to try and put that back together as it was and make sure it’s gonna last. I suppose it was a good thing that it was originally built with sand cement, because if it was bonded with lime mortar, it wouldn’t have withstood the two bombs that nearly hit it in World War II. The bomb damage is part of the listing for Exhibition Road. There’s a plaque at the bottom of the AWS that describes it. It’s important for the history of that area and for London that the damage is preserved. We were very careful when rebuilding it, and photo surveys done before dismantling helped us put back the damaged sections exactly where they were taken down from.

Part II: The Return

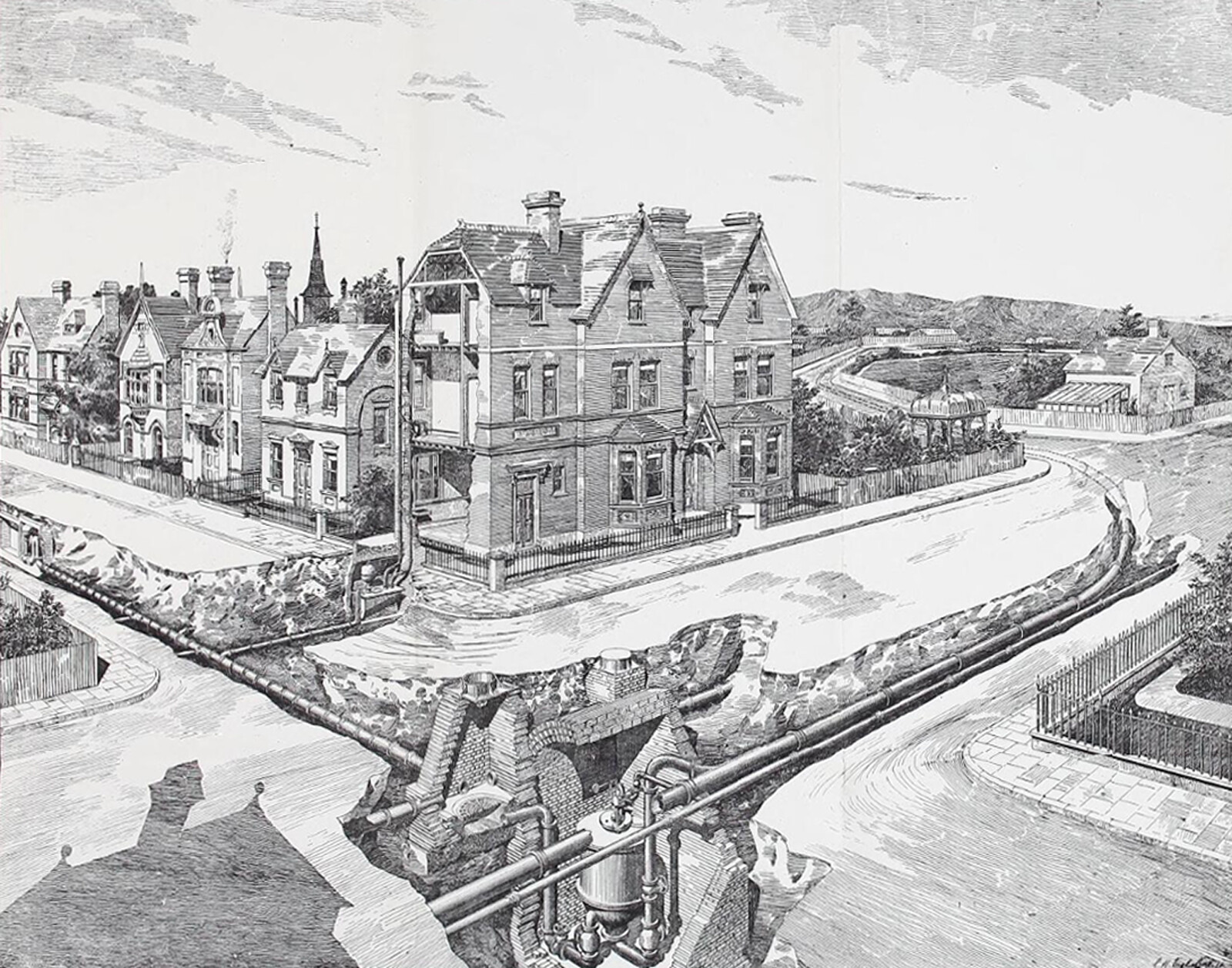

In 2017, two years after they were removed, the Portland Stone ashlars carved out of the AWS by Rees and his team caught the attention of the owner of a quarry in Dorset. They had been stored in a warehouse in Swindon and were probably destined for the crusher—like most stone from demolished buildings and structures. But the quarry owner saw some value (perhaps not economic, but heritage) in them, so they were saved from the maw of the stone crusher and trucked three hours west of London, placed on pallets, and allowed to rest. No one had any idea what to do with them, and they were taking up valuable storage space next to the quarry pit, but that was better than seeing these one-hundred-and-fifty-million-year-old stones, beautifully and strenuously worked a hundred years ago, destroyed.

Portland stone from the AWS languishes in a Dorset quarry. Photo: Juliet Haysom.

AWS stone sitting in Dorset quarry. Photo: Juliet Haysom.

Moving the AWS ashlars. Photo: Juliet Haysom.

Portland stone from the AWS languishes in a Dorset quarry. Photo: Juliet Haysom.

Portland stone from the AWS languishes in a Dorset quarry. Photo: Juliet Haysom.

The entrance we see today on Exhibition Road is an evolution of Victorian heritage to fit the contemporary demands of public space. Another of those demands is safety. This is where an unlikely new chapter in the life of the ashlars carved out of the wall and taken to Dorset begins. Hostile Vehicle Mitigation is now a requirement in London’s public spaces, especially those as prestigious and busy as Exhibition Road. The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea planned—and is still planning—to import huge granite monoliths that were mined in India and worked in Italy and use them as barriers between the pavement and the road; a boundary which is already deliberately unclear on Exhibition Road—a strategy to make everyone slow down.

In the summer of 2021, we were commissioned by the London Design Festival to produce a project at the V&A. We knew about the abandoned ashlars, so proposed to bring a selection of these back to Exhibition Road. This involved first producing a detailed survey of the 450 stones stored in the quarry, and then designing three combinations of the existing stone geometries into street furniture. The cutting, cleaning, and dressing was done by Haysom Purbeck Stone in Dorset; the heavy lifting, and the setting-in-place in London was once again done by Paye and Rees.

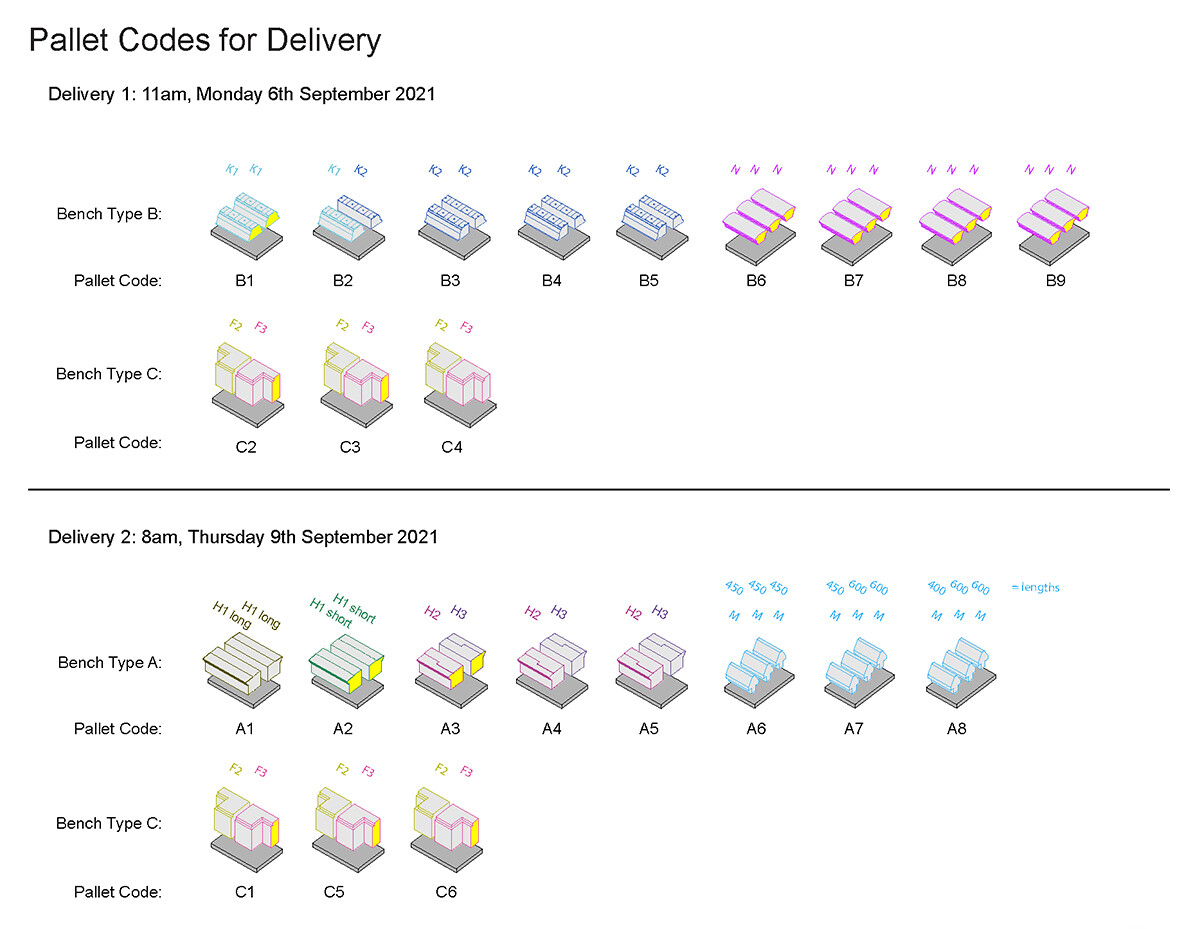

Pallet schedule. Drawing: Juliet Haysom.

For now, a new material dialogue has been created on Exhibition Road between the “new” benches (they cannot be called that, officially, but that is, of course, how they are used) and the V&A entrance from which they were carved out. It seems a much more logical and enriching fate for them than the stone crusher. They both reference and rearrange some of the V&A’s history, while pointing towards a future where the locality of materials is more highly valued.

Planning permission has been granted for the stones to remain until December 2022. The council’s official plan is still to import the granite monoliths and install them where the benches currently sit. But no date or details have been given for this process, and Dixon Jones, the monolith’s original designers, have since gone out of business.

Placeholders with reconfigured AWS in the background. Photo: David Grandorge.

Placeholders in use. Photo: David Grandorge.

New bench, old material. Photo: David Grandorge.

Placeholders in use. Photo: David Grandorge.

Placeholders with reconfigured AWS in the background. Photo: David Grandorge.

It is hard to reconcile the UK’s Net Zero carbon ambitions (and those in the 2021 London Plan) with the intention to ship many tons of granite from India, carve them in Italy, then ship them to the UK, all to serve a purpose that is already being fulfilled by a local and historic material. Imported stones account for at least double the embedded energy of local stones.

This project invites a larger debate about public authorities’ responsibilities when procuring material. Shouldn’t they be leading a future model of the industry, encouraging local recirculation of material rather than perpetuating practices that, at a policy level, look already obsolete?

Although some lessons can be learned from the conservation practice and trade, the attitude to recirculate our building stock will require a new type of expertise, one that sits between the speed of demolition companies, which work hand-in-hand with the recycling industry—streamlining components from buildings to crushers and to aggregate—and the often-unaffordable dexterity and care of the conservation trade, where every stone is treated as a heritage masterpiece. This middle trade will aim to give salvage a chance, but also accept loss. It would also need to reinvent dismantling techniques to operate at a larger scale, and faster, than the current process performed for listed buildings.

Rather than a neat and tidy circularity, the built environment exists in a chain of material events, and the outcome is never final. Instead, it is undecided. That’s where agency lies, beyond the need for a lot of designing, precision cutting, and heavy lifting.

From the Ancient Greek: αναστήλωσις, -εως; ανα, ana = “again”, and στηλόω = to erect {a stela or building}.

Digestion is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 2022 Tallinn Architecture Biennale, supported by the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC), the Estonian Museum of Architecture, and Friendship Products.

Category

Subject

Placeholders was commissioned by the London Design Festival 2021 at the Victoria and Albert Museum London curated by Meneesha Kellay and Catriona Macdonald. It was designed and produced by Aude-Line Duliere and Juliet Haysom, with a documentary by Ele Mun. It was supported by Wallonia Brussels International (WBI), Wallonia Brussels Architecture (WBA) and produced in partnership with PAYE Stonework and Restoration. Project collaborators: Mark Haysom (Haysom Purbeck Stone), Rotor, Hugo Corbett, James Westcott.