The more humans created a human-dominated world order, an order of life, the more we got rid of most of the wildlife that could have threatened it. And we developed mechanisms for dealing with “natural” disasters, ranging from technology to insurance. The only predators we have left now are viruses, bacteria, and other microbes. In a way, this happened by combining caring with scaling up.

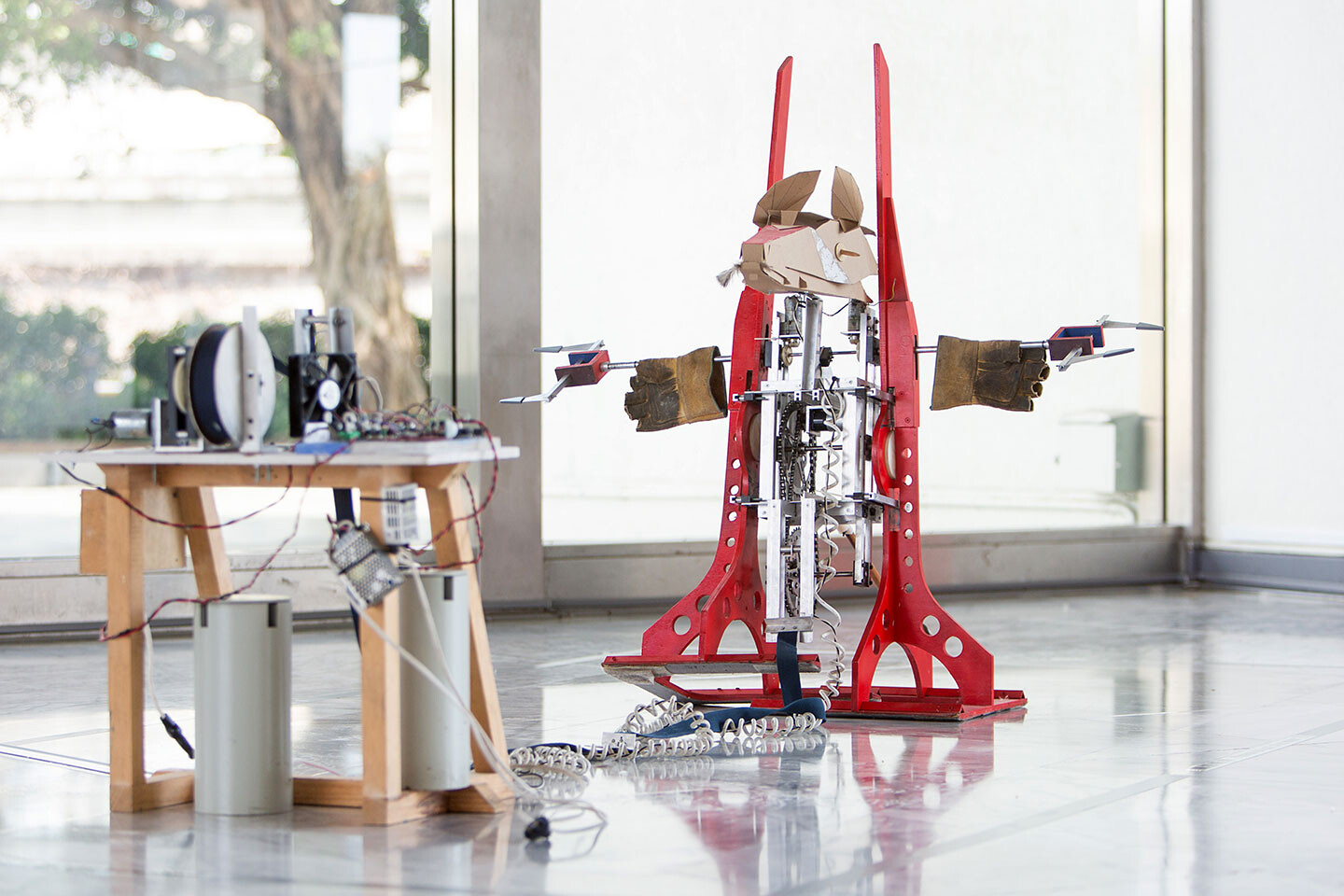

June Balthazard and Pierre Pauze, Mass, 2020. Two-channel video, wood, foam, Polychoc, polyester resin, water paint, plaster, pmma laminated, synthetic plants, bumper, steel, stage light, light stand, dimensions variable. Commissioned by Hermès Horloger, Bienne, Switzerland and Taipei Biennial. Courtesy of the artist and Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

On the occasion of the Taipei Biennial 2020 and together with the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), this special issue of e-flux journal will also be available to read in Chinese in 2021. Titled “You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet,” the issue deals with an increasingly pressing situation: people “around” the world no longer agree on what it means to live “on” earth—to such a radical extent that the foundational material and existential categories of “earth” and “world” are profoundly destabilized.

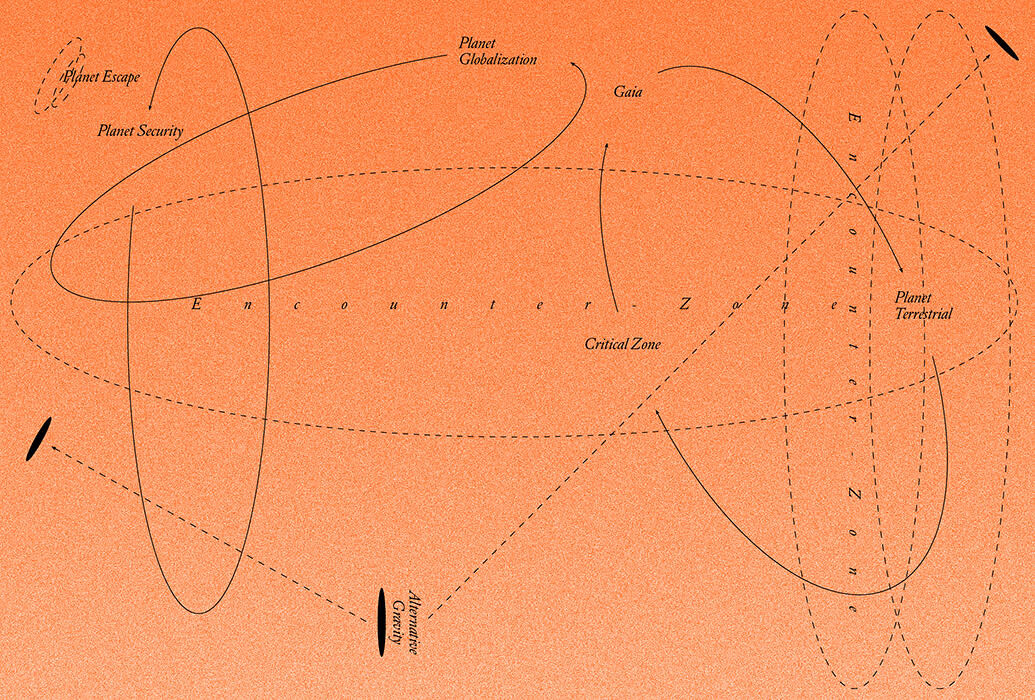

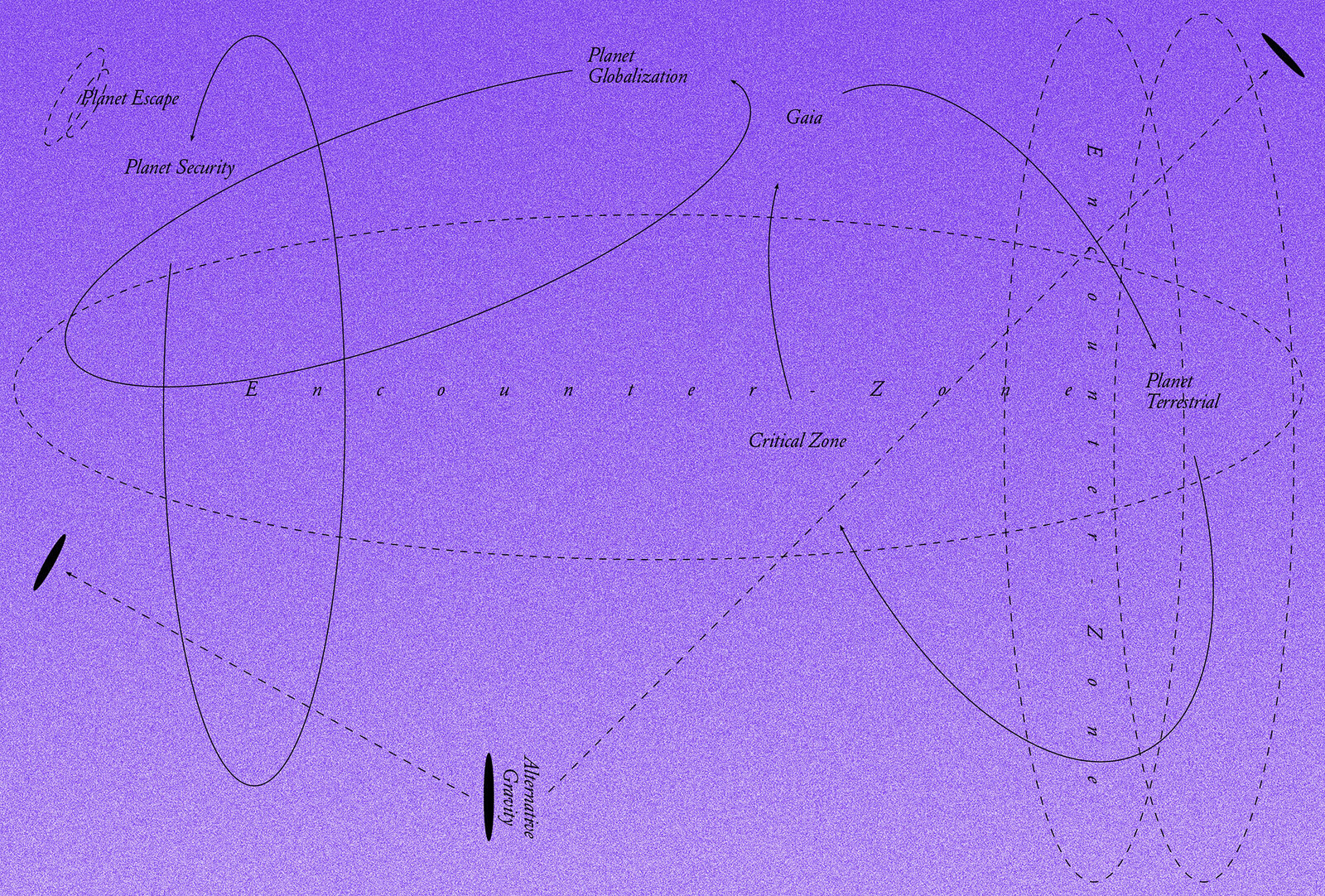

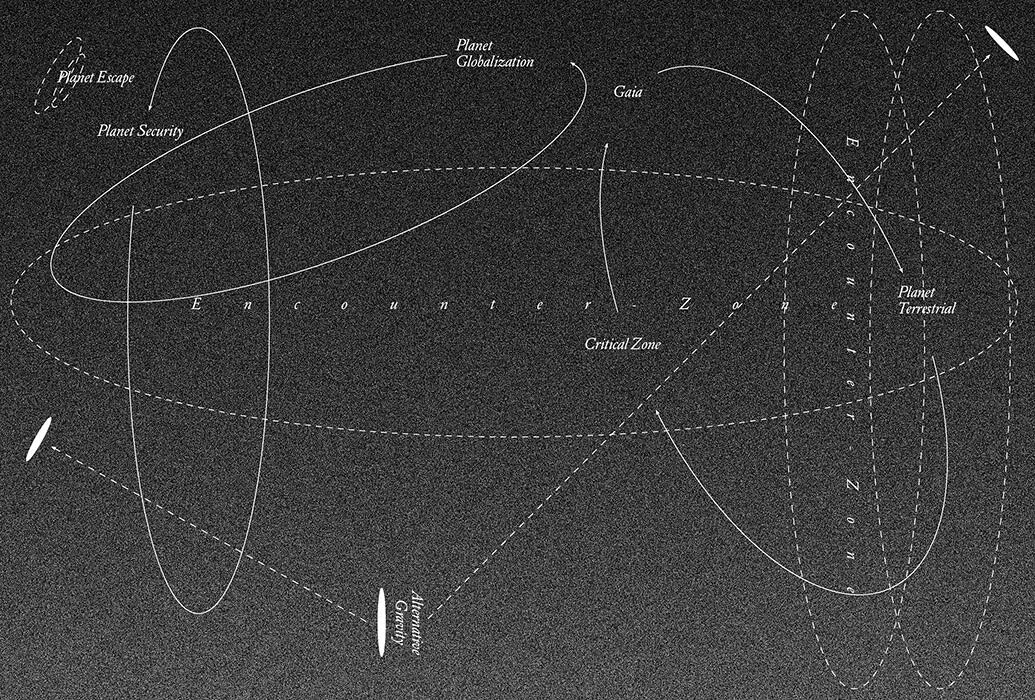

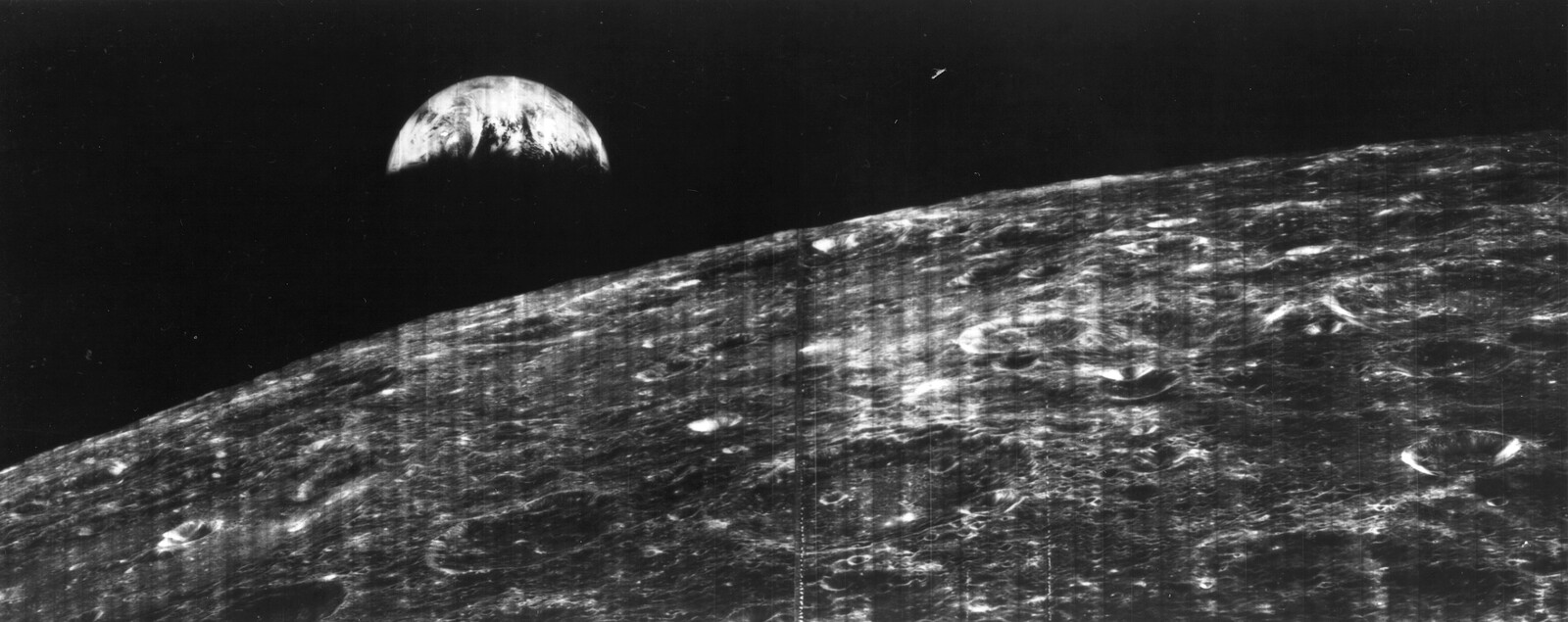

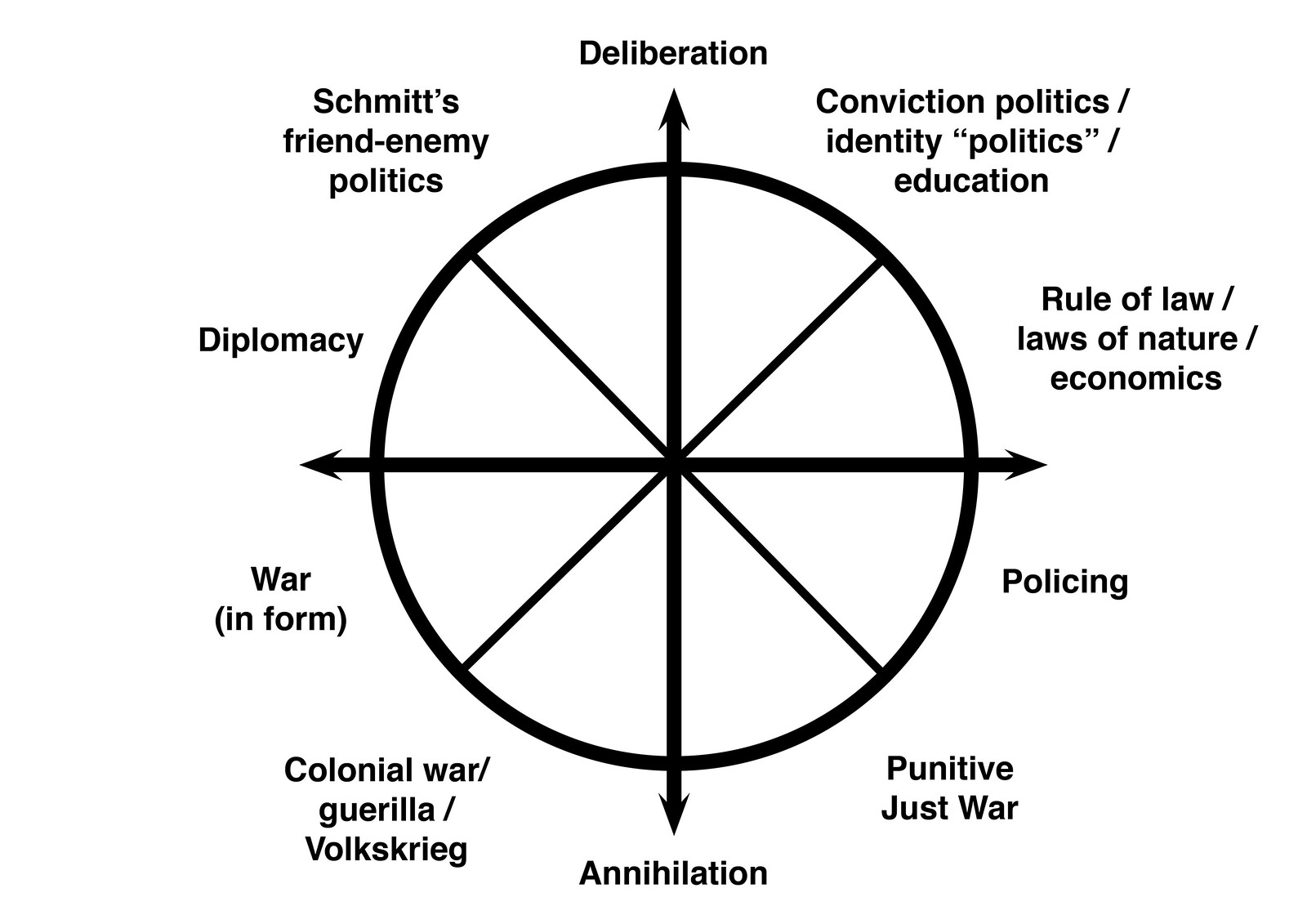

The singular image of the blue marble is now divided into different worlds which form a constellation that has nothing to do with celestial harmony. We are caught within it, where for each decision we must make, the gravitational attractions of the different configurations of earth make one’s head rotate as if on a merry-go-round. The model for describing this condition is not just some new form of dialectic (implying only two poles), but rather a configuration with a multiplicity of polarities.

Despite billionaires fleeing to New Zealand and Mars, we’re far too connected by oceans, weather, communications, and diseases for any of us to go it alone. We again need to see the earth as a whole. This is all the more true since the planet photographed from space failed to birth an unequivocally better world.

When did things start to go wrong? It is hard not to ask that question nowadays. By “things” we mean, of course, “nous autres,” those civilizations that are now known to be mortal, as Valéry lamented in 1919, using a plural to speak of a singular, modern European civilization, whose future was the object of his deep concern. Today, this singular has become even more evidently and disturbingly a universal, the techno-spiritual monoculture of the species.

Enfolding, folding, unfolding, and entangling—in the solar system, where everything is revolving around everything else, the Baroque formation of life on earth is always already a work of art. Meanwhile, it is a definite politics of boundaries that we cannot ignore.

The desire for new narratives, as well as for reconnection with sources from precolonial Africa, is perceptible among young people in Senegal and in Sébikotane in particular. They are opting and organizing to stay in Senegal, to keep inhabiting the territory, despite being confronted by all sorts of dangers that threaten, crush, and deny life every day. It is this permanent revolutionary future that we try to capture on film.

The idea that diplomats today could help us articulate what divides us should not be abandoned. But it needs to be resituated in a new environment.

Diasporic existence is a refusal, the refusal to choose between two worlds. This refusal assumes a singular form when the two worlds are in conflict. It summons a whole vital economy that contests a geopolitics founded on the logic of predator and victim.

Sense-making (Besinnung) cannot be restored through the negation of planetarization. Rather, thinking has to overcome this condition. This is a matter of life and death. We may want to call this kind of thinking, which is already taking form but has yet to be formulated, “planetary thinking.”

With the cybernetization of the world, both the human and the divine are downloaded into a multitude of tech objects, interactive screens, and physical machines. These objects have become genuine crucibles in which visions and beliefs, the contemporary metamorphoses of faith, are forged. From this standpoint, contemporary technological religions are expressions of animism.

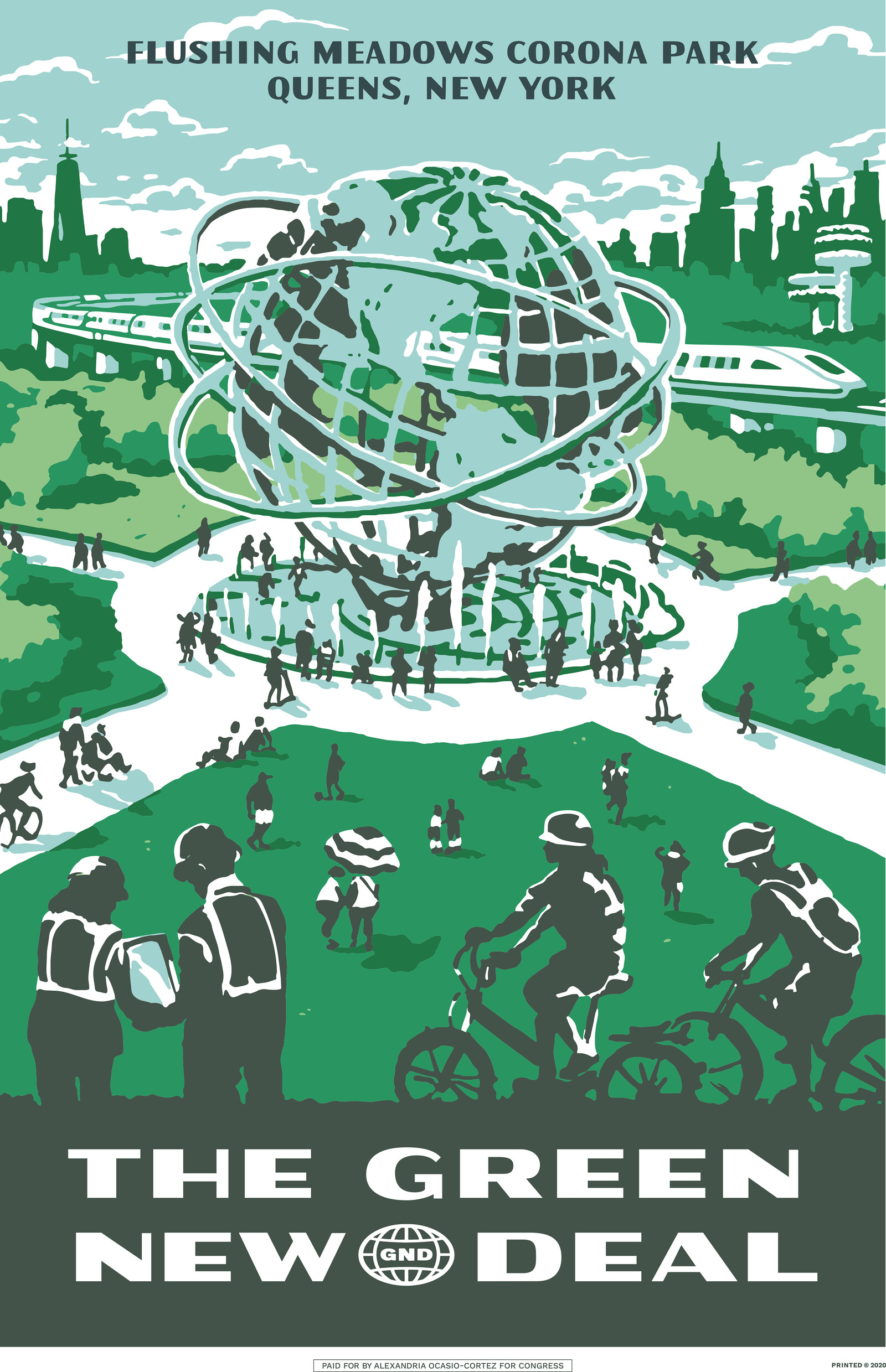

The shaping of post-carbon politics is not a peaceful landing in the world of shared interests, but rather a theater of rivalries organized around new infrastructures, new assemblages between political power and the mobilization of the earth.

The world is divided, as Bruno Latour puts it, not only in relation to environmental politics but also, and even more sharply, in relation to sexual and reproductive politics. A new hot war divides the world into two blocs: on one side, the techno-patriarchal empire and, on the other, the territory where it is still possible to negotiate gestational sovereignty.

There is every reason to think that profound shifts are breaking the impasse that has defined our reality for the last thirty years. This is not to say that we do not face a divided and unequal world set on a disastrous course, but rather that the key players and the terms of the negotiation are shifting.

Whereas most borders enforce separation, the shoreline is a threshold marked by ceaseless negotiation. It is a site of arrivals and departures, of safe harbors and hostile intrusions. At once embedded in local traditions and subject to industrial development, it hosts encounters between different populations and environments, the terrestrial and the aquatic.