The Avant-Garde Museum

The avant-garde wanted to demolish museums, believing they served to petrify and cultivate the past, which needed to be discarded in the name of a better tomorrow. But the avant-garde also dreamed of its own museums, places governed not by history, but by the future. They were imagined as laboratories where the artist would experiment with new forms and means of expression, and the viewer would learn to experience and understand reality in a new way. The museum became a vehicle for fulfilling the avant-garde utopia—the promise of a world where everyone has the right to and conditions for a creative life.

The history of avant-garde museology begins after the October Revolution, when the Russian champions of new art proposed the establishment of a network of Museums of Artistic Culture. Not much later, a group of New-York-based modernists and Dadaists started the Société Anonyme, a collective that sought to establish the first American museum of modern art. The successive chapters of this story were written by the Russian Constructivist El Lissitzky, who designed the Kabinett der Abstrakten at the Hanover Provinzialmuseum, and by the avant-garde a.r. group, whose efforts began the International Collection of Modern Art at the Łódź museum now known as the Muzeum Sztuki.

We mention these facts not only because they are an important, yet neglected part of the avant-garde legacy. First and foremost, we believe the ideas that informed the founders of avant-garde museums and the solutions they implemented still raise vital questions. What should the museum be like? What role should it play in society?

Reviews

“Requiem for a Dream” •

THE IDEA OF AN AVANT-GARDE MUSEUM has something of the head-scratching quality of the oxymoron to it—because didn’t the avant-garde turn its back on institutions in hopes of engaging directly with life? (That said, why people consider institutions anathema to life has always been another head-scratcher for me.) In his 1909 Futurist Manifesto, F….

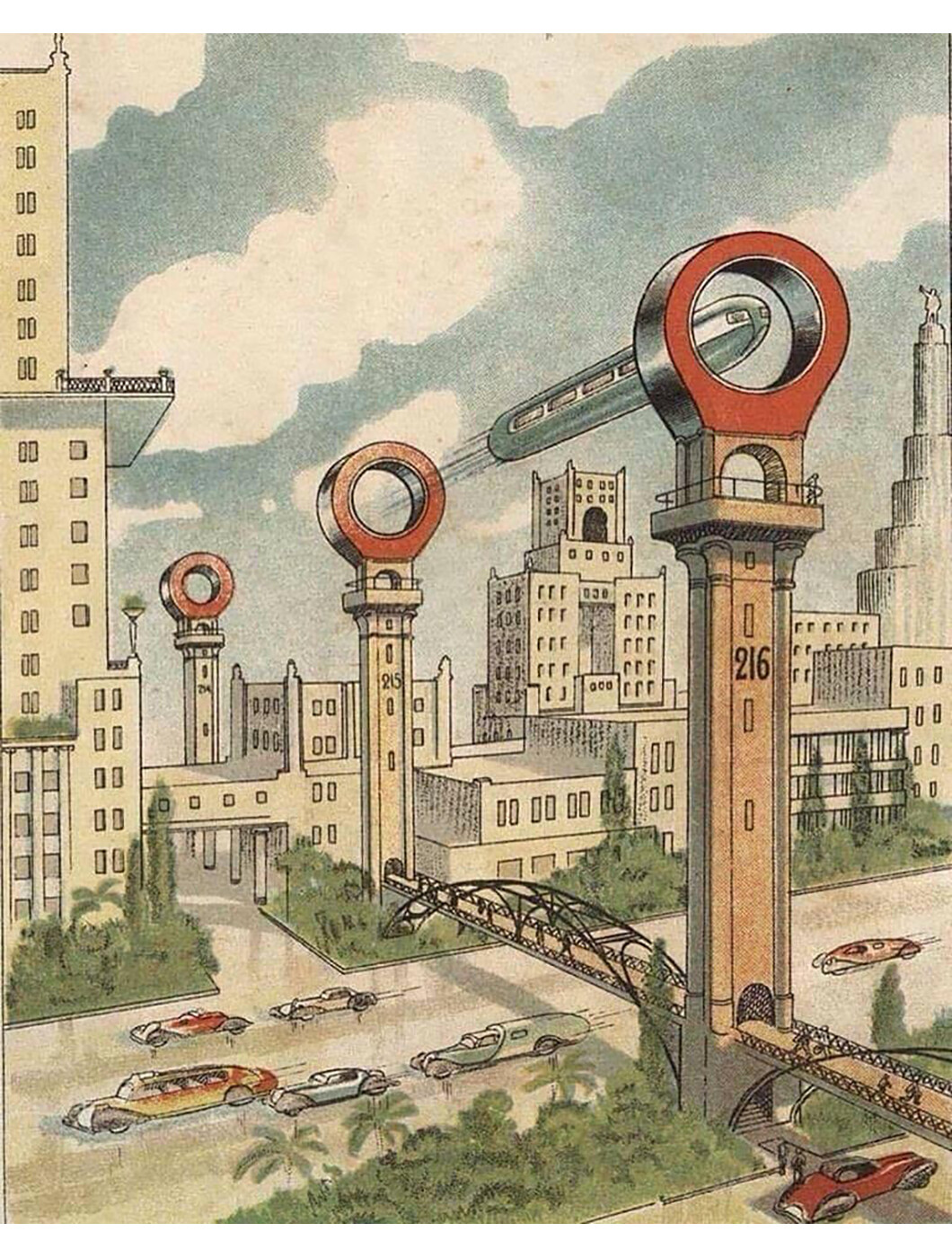

THE IDEA OF AN AVANT-GARDE MUSEUM has something of the head-scratching quality of the oxymoron to it—because didn’t the avant-garde turn its back on institutions in hopes of engaging directly with life? (That said, why people consider institutions anathema to life has always been another head-scratcher for me.) In his 1909 Futurist Manifesto, F. T. Marinetti promised to destroy museums and other dusty sites of knowledge (“libraries, academies of every kind”) in order to make space for speed and dynamism. But ten years later, over in Russia, Kazimir Malevich used language similar to Marinetti’s (“We need to act against the old, to bury it in the cemetery for forever and a day, to scrub any semblance to the past off our face”) to imagine a “network of museums” that would allow “the best creative works” to “penetrate deep into the country” and “give an impetus to the remaking of forms in life and artistic images in industry.” Yes, Marinetti and Malevich both agree, art must escape history’s shadow, but for Malevich, at least, modernity didn’t so much mean razing the past as it did reconstructing its institutions to spread the message of the day.

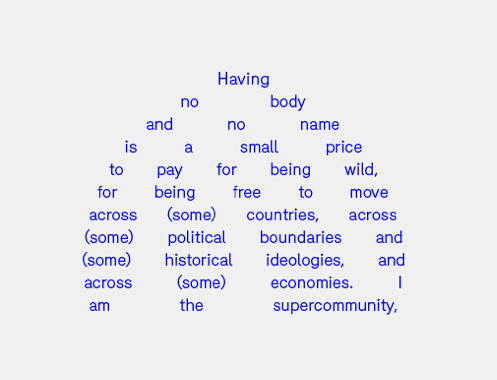

The story of this strange structure is told in The Avant-Garde Museum, a recent anthology–cum–exhibition catalogue edited by Agnieszka Pindera and Jarosław Suchan and published by the Muzeum Sztuki in Lodz, Poland, an institution that is itself a product of the avant-garde tendencies that the book seeks to document. (The related show is set to open at the museum this October in celebration of “100 years of the avant-garde in Poland.”) Weighing in at more than six hundred pages and featuring twelve scholarly essays, a host of primary-source documents, and a dossier of color reproductions, the book contains a huge trove of knowledge. The case studies cover collecting institutions in the United States, Europe, and Russia, from the itinerant Société Anonyme, founded by the collector-painter Katherine Dreier and artists Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, to the Museums of Artistic Culture led, in part, by the Russian Constructivists Lyubov Popova and Aleksandr Rodchenko. While internationalism is one of the avant-garde’s defining features—its dream of distribution, whether in the form of little magazines or demonstrations, was part and parcel of its mission—because the avant-garde museum sits on terra firma, the question of national locations and political contexts becomes pressing. One wonders, for example, if the Société Anonyme, an institution founded by the heir of an American steel magnate, can really be compared to Soviet state-sponsored projects that sought to transfer power to “workers and peasants” and to remake the museum into a laboratory of “artistic invention.” And how much can either share with the International Collection of Modern Art, begun in Poland by Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński, which pooled far-flung modernisms in order to forge a modern Polish national identity? Are all politics local? And is all art as well? What we see in this volume is what it looks like when a shared idea, and shared idealism, comes down to earth.

In the past two decades or so, the history of modernism has been told increasingly through the lens of exhibitions. This approach has allowed scholars to counter broad claims for art’s autonomy by returning artworks to time and space, as well as specific publics and systems of display. Certainly, modernity finds a fitting form in the exhibition. Emerging with the Salon and tangled up with trade shows and world’s fairs, it is a necessarily impure assemblage, carrying ephemerality and sceneyness in its bones. But the emphasis on exhibitions has also to some extent eclipsed an investigation of modern institutions, and the very idea of the collection—the question, that is, not simply of what to exhibit but of what to keep. The history of exhibitions has done vital work, but what we need today—perhaps more than ever—is a history of institutions. While there have been monographic exhibitions and catalogues dedicated to institutional bodies such as the spiritualist Museum of Non-Objective Painting (now New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum) and the Societé Anonyme, itself the offspring of Theosophical energies, the avant-garde museum as a type has never been cogently theorized. This volume is a perfect place to start.

Though much of the history told here is somewhat canonical, one of the book’s strengths is the way in which it reframes artists and artistic practices we thought we knew. El Lissitzky’s Kabinett der Abstrakten (Abstract Cabinet) is a key example. In museums in Hanover and later in Dresden, Lissitzky created spaces of shimmer and movement by installing metallic rods and movable panels on gallery walls to encourage viewers to participate in the artwork’s organization. Attention to installation is also key to Strzemiński’s red, yellow, and blue 1948 Neoplastic Room, the crown jewel of the Lodz museum, which offers a Mondrian-like space that matches the work it holds. While both projects conjure something of the spirit of the cabinet of curiosities, a pre-Enlightenment model of wonder that offers a riposte to the modern museum’s rationalizing order, many proponents of the avant-garde museum sought more futuristic models. One such figure was Alexander Dorner, the commissioner of Lissitzky’s Cabinet, who is now regarded as one of the great imagineers of the twentieth-century exhibition form. Though most avant-garde museums were artist-run, Dorner—working first in Germany, where he led Hanover’s Provinzialmuseum, and later in the United States, where he was director of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum—was the odd administrator fond of bold, bravura proclamations. In his 1947 book The Way Beyond “Art”, he declared the modern museum to be “a kind of powerhouse, a producer of new energies,” made of both “light modern materials” and “moral strength.” But like many avant-garde projects, Dorner’s ideal museum remained paper architecture, and in time the desire to bind together a new art and a new vision in a new museum began to seem overly heroic—and perhaps overly rhetorical, too.

The new generation of art workers scrutinize flowcharts, payroll, and fundraising the way earlier generations argued over medium specificity, facture, and “the crisis of representation.”

For every grand claim, there is a quotidian reality, and, like it or not, when you study the museum, you enter the realm of the bureaucratic, which can be fairly mundane stuff. So perhaps it’s fitting that the great insight contained in this volume is packaged in something with the look and feel of a phone book. There is a kind of granular detail at work in many of the texts, too, that is almost forensic in its fastidiousness; we learn, for example, that Lissitzky specified strips of chromium-nickel-alloy composite at 1.5 x .04 inches. But perhaps these bits of seeming arcana remind us that part of the work of building institutions, no matter how radical, will inevitably be somewhat tedious, and that what happens in the cubicles and boardrooms behind the white cube is just as important as what goes on inside of it. (“It is not enough to create a good work of art,” Strzemiński wrote. “It is also necessary to create the right conditions for it to have an impact.”) Indeed, with each museum unionization today, it becomes clear that the institution of art need not be a space of sacrifice; rather, it might be a site where rights are secured, where resources are pooled and distributed. This is due, in part, to the new generation of art workers, who scrutinize flowcharts, payroll, and fundraising the way earlier generations argued over medium specificity, facture, and “the crisis of representation.” Will they feel suddenly modest when their struggles are written about and historicized in the future? Will they want the “work”—the performances they staged and exhibitions they organized—to be foregrounded instead? Probably not. We’re moving toward a more holistic understanding of the institution of art, wherein the site of display and the back of the house are increasingly indivisible from each other. (Hegel’s schema has progressed: Art today is not Romantic but Institutional.) Like our coffee, we want our art to be both bold and fair trade.

DEVOTED TO A NETWORK of institutions shaped and fostered by the historical avant-gardes, this chronicle doesn’t get much beyond the postwar moment, nor does it venture far outside an expanded Europe, which left me wondering what the next chapters might be. While some of the institutions documented in the book folded and donated their works (the collection of the Societé Anonyme, for example, was shipped off to Yale in 1941), the one or two still kicking seek to rekindle their legacies via recurring bouts of nostalgia, self-love, and revolutionary ardor. They have also become sites of pilgrimage for contemporary artists with an archival bent—see, for example, R. H. Quaytman’s 2019–20 series of paintings “Chapter 35: The Sun Does Not Move” and the 1998 film Phantom Limb by Union Gaucha Productions, both focusing on Kobro and Strzemiński’s work at the Muzeum Sztuki. But, by and large, the dream of the avant-garde museum, like that of the Museums of Artistic Culture, of which there were hundreds if not thousands (a proper revolutionary network, to be sure), has vanished into historical oblivion, which is precisely what makes this volume so important. It’s an archive waiting to be mined.

This volume also asks one to consider the institutions that followed in the footsteps of these now-mythical museums—what might be called neo-avant-garde museums. Though one dream of the 1960s was to leave the museum and get out into the environment, there was also a countertendency among wry artist-protagonists to concoct ersatz museums that reflected coyly on the institutions of art. Think, for example, of Marcel Broodthaers’s museum, begun in 1968, devoted to eagles, replete with signage and crates but possessing no permanent home; or of Claes Oldenburg’s 1965 Mouse Museum, a freestanding structure full of lumpen items with ears shaped like Mickey’s. (A Ray Gun Wing was added in 1977 for an exhibition in Chicago.) In many ways, these projects represent a massive downgrade in scale and ambition from what came before—these are self-conscious antihero museums—and in retrospect, it’s difficult not to feel a sense of loss when surveying them. Despite their intelligence and acuity, they demonstrate the drastically reduced conditions of possibility for radical practice in the postwar era.

But there are other cases, too. It would be interesting to consider, for example, New York’s Studio Museum in Harlem in the tradition of the avant-garde museum. Imagined as a space of production, archiving, and display, the Studio Museum, which first set up shop above a liquor store just off 125th Street the same year Broodthaers founded his museum of eagles, sought to carve out a space for a community of artists and for the community at large. Its founders felt that the two were inextricable, that you couldn’t separate one from the other, that, indeed, progressive institutions were integral to progressive possibilities outside their doors. Many of the museums working in an avant-garde genealogy today carry on this legacy, whether it be the Underground Museum in Los Angeles or the Artist’s Institute in New York or Casco Art Institute in Utrecht, the Netherlands. (In her 2013 book, Radical Museology, Claire Bishop proposes the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, and Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova in Ljubljana as vanguard candidates.) Splitting the difference between the heroism of historical avant-gardes and the wit of their neo-avant-garde counterweights, these small institutions face their realities with a determined mix of modesty, agility, and sincerity. While one contribution in the Muzeum Sztuki volume hypothesizes about contemporary museums with departments of “social activism,” not all these institutions define their mission so programmatically. Maybe there’s still something about art that wants to be oblique.

Perhaps most pressing today, one also wonders if a traditional museum can turn avant-garde, if privatized capital can be transformed, like Rumpel-stiltskin’s straw, into a public resource, if permanent collections can ever really be held in the public trust. Many are trying, whether from within (say, curators shaping their programming for nontraditional publics) or from without (activists demanding institutions reassess their funding sources), and the old question arises once again: Where is the most effective place to do the work? It’s become clear now that it’s not an either/or answer. The relationship is symbiotic. The institution and its outside form a call and response, just as the multiple components of the museum (curator, custodian, educator, trustee) create their own ecosystem, with moments of discord, strife, compromise, and contestation alike. So let’s not give up on this dream. The avant-garde museum is dead, long live the avant-garde museum!

Alex Kitnick teaches art history at Bard College in Annandale-On-Hudson, NY.