The Macon Housing Authority says they may have found a time capsule buried in the ground. The CEO of the authority, June Parker, says they discovered a box that looks like a safe underground by a flag pole outside of the Technical Service Building. Parker says the box could be empty, but she says it also could be some kind of time capsule. The Macon Housing Authority will open the box Monday at 4 p.m. to reveal what is inside.1

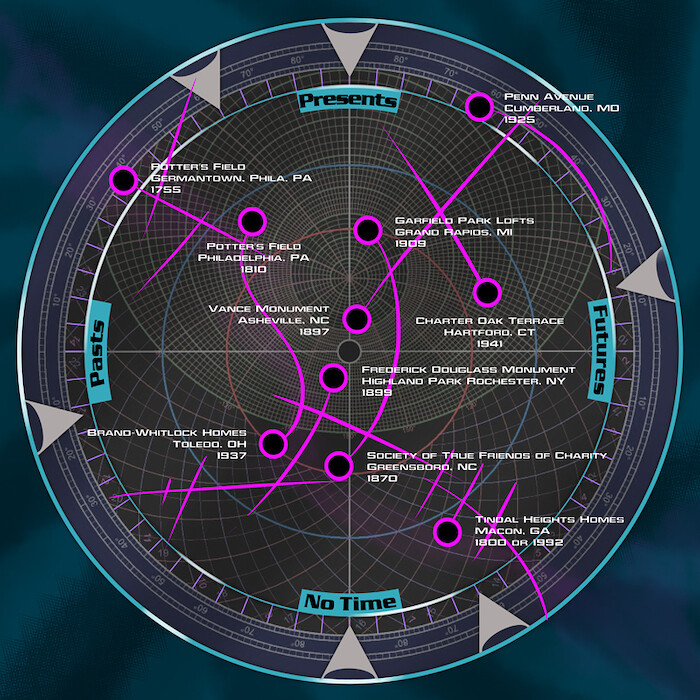

In the summer of 2017, a mysterious safe with time capsule-like contents was discovered beneath the grounds of a public housing site owned by the Macon Housing Authority, Tindall Heights, that was being redeveloped in Macon, Georgia. Several others have been unearthed at the sites or future sites of public housing projects. A time capsule dating back to 1925 was found in 2011 at the site of a future affordable housing project in Cumberland, Maryland. Another, dating back to 1937, was unearthed during the demolition of the Brand-Whitlock public housing complex in Toledo, Ohio in 2013. Another, from 1941, was discovered as the “blighted” Charter Oak Terrace public housing site came tumbling down in Hartford, Connecticut in 1997. A capsule from 1909 was found at the Garfield Park Lofts in Grand Rapids Michigan, the former site of Burton Heights Methodist Church, which is managed today by Michigan State Housing Development Authority.

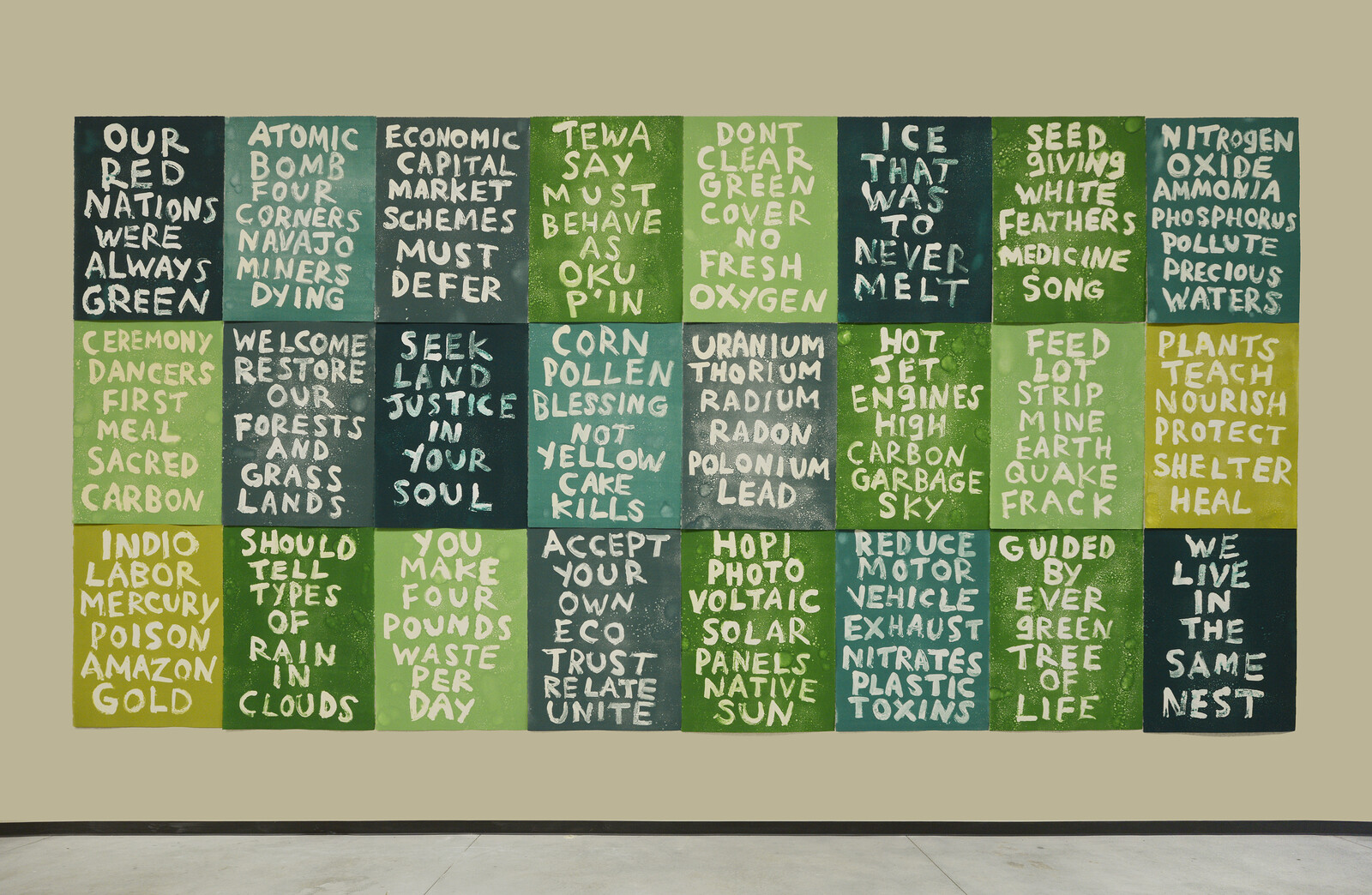

Time Capsule Map by Black Quantum Futurism, 2021.

Time capsules date back to the beginning of humanity’s marking of time, and typically represent different traditions and understandings of time and temporality. However, modern time capsules as we know them are often thought of as a Western linear temporal ritual. Creating and burying time capsules is highly popular and well-documented in America: it is often done at baby showers, buried at building dedications, weddings, buried at school events, or even used for personal reasons.

Objects placed inside time capsules are usually mundane. Their contents are not useful per se, and are usually not particularly unique. Time capsules in Western traditions operate from past to future on the timeline of progress: something is buried in the present for the future to learn about their past. According to William E. Jarvis, time capsules in the American tradition must also be built in a certain way that allows them to survive the test of time, “notify future recipients of its existence at a precise location,” and perhaps most importantly, “select and preserve contents.”2

A scan of traditional time capsules contents and time capsule histories provides little evidence that traditional American time capsules are created for Black future generations. The histories found inside of these time capsules rarely account for the presence of Black people, while Black future generations are diligently erased from the envisioned futures of traditional time capsule buriers.

Time capsule found buried several feet underground in the Tindall Heights redevelopment construction site in Macon, Georgia. Source: The Macon Telegraph, still from video by Beau Cabell, July 2017.

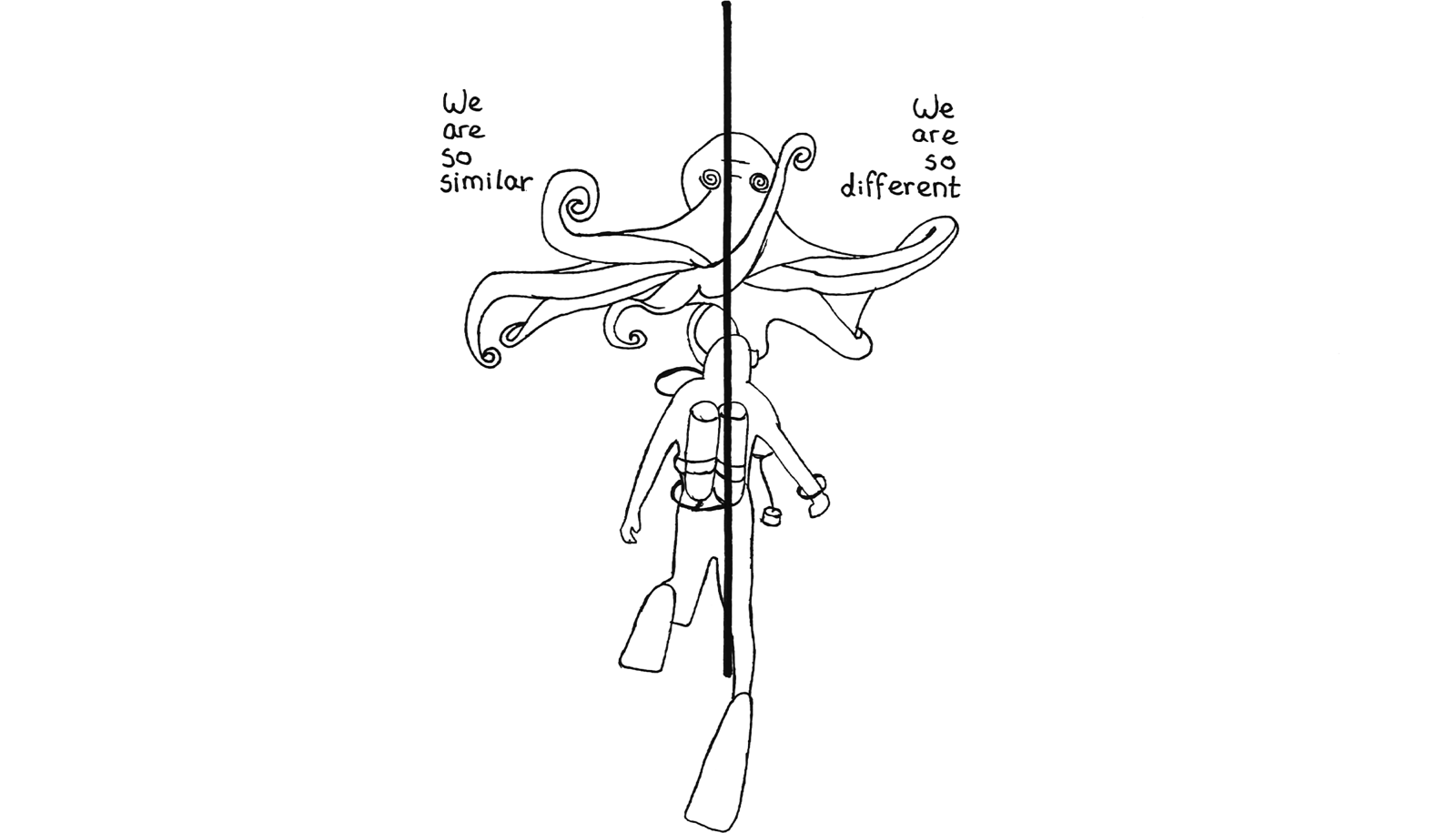

The pattern of unearthed time capsules at sites of affordable housing is therefore critical. Their contents offer alternative, lost, and otherwise obscured histories. Marginalized Black and Brown communities are often disproportionately impacted not just by material and spatial inequalities, but also temporal inequalities, or what sociologist Jeremy Rifkin calls “time ghettos.”3 Time capsules buried within or underneath housing projects tend not to have a specified “opening” date attached to them, which makes them fall, by some accounts, outside of their traditional definition.4 But uprooted in the midst of redevelopment, these time capsules work to reverse the exclusion of Black people as actors in the events that fall upon the timeline of Western progress.

It’s not clear when the time capsule was sealed, although the latest identifiable documents appeared to be from 1937. The Brand Whitlock Homes opened in 1938. The public housing complex was among the nation’s earliest, built by the New Deal-era Public Works Administration to provide affordable housing and employment for out-of-work skilled tradesmen and construction workers … The capsule’s contents tell the background of how the Brand Whitlock Homes came to be built: a 1934 study of housing in Toledo noting many central-city homes’ poor condition and the high number of tuberculosis cases in the area, one of the few parts of the city where blacks were permitted to live at the time; newspaper clippings about the New Deal-era program to build the housing; the Public Works Administration’s blueprints for the complex; a program from the August 2, 1936, groundbreaking ceremony; and well-preserved copies of The Toledo Blade and Toledo News-Bee from August 25, 1937, and the Toledo Morning Times from August 26, 1937.5

For example, the time capsule found at the Brand Whitlock Homes in Toledo, Ohio gave a then-present snapshot on the practices of racially restrictive covenants that prevented property owners from selling homes to Black people and other people of color, and kept them locked them out of affordable, habitable homes on the rental market, forcing them into segregated areas of racially concentrated poverty. As Black people were driven further into segregation in neglected and crowded housing, rentals became associated with poverty, blight, transiency, and lower property values. According to one document preserved in the capsule, the Homes were built in one of the “four sections of the City of Toledo where Negroes are permitted to rent or purchase homes,” and where “many of those homes lacked running water or electricity. The conditions of the area fostered poor health conditions, including many instances of tuberculosis, as well as high rates of vice and crime.”6 Another document in the capsule included a speech by Black civil rights activist and pharmacist Mrs. Ella P. Stewart, where “she outlines the history and progression of the Negro in Toledo, with emphasis on their occupational and educational development.”7

The Brand Whitlock time capsule contains both the evidence of an inadequate present in 1937, as well as the hopes for a radically changed future for the Black people in that community. Its eventual unearthing in the midst of demolishing the Homes due to their severe neglect might be seen as a failure of the promises of the time capsule by normal standards, or might not be considered a time capsule in the first place, given that it had no specific opening date. To put it another way, had the visions in the time capsule manifested, it would have never been found because the Homes would not have gotten to such a point of disinvestment and neglect. But the uncovering of the Brand Whitlock Homes time capsule is ultimately a revelation of the non-linearity of progress for Black people when measured against a standard timeline, and a need for different understandings of time and the ways that Black people transmit memories and future visions across and between generations.

Quantum Time Capsules

Quantum time capsules are temporal technologies for oppressed Black and Brown people isolated in local, progressive, linear, fatalistic time ghettos that otherwise deny access to temporal dimensions. Quantum time capsules can send messages and objects to any point in the past or future, communicating with both ancestors and future generations. They elude linear space-time and trouble our notions of past, present, future, history, and progress by including stories and objects usually rendered invisible. As a way of communicating with the past and connecting with the future, quantum time capsules can help us unsettle and question expired presumptions and understandings of time.

Black cultural artifacts and sites of memory are never present to the white gaze unless they are being used for capital appropriation, exploitation, and accumulation. In excavating cabins of enslaved Africans and Black burial grounds, researchers have come across artifacts that appear to them to be “miscellaneous piles of junk.”8 Untethering the “junk” from the white gaze and imagination requires seeing these objects not as functional, but as artifacts of memory and meaning that store energy and restore context and subjectivity. Divorced from their commodified value, the “junk” placed into or taken out of quantum time capsules have compelling stories to tell.

This was my Great Grandmother’s

this lucky hot comb

it’ll get you a job,

get you out the poor house,

got yo Granny out the ghetto

and yo Momma outta section 8

in ’merica this hot comb

is a portal

Colored Peoples’ Time Capsules

William Faulkner, in Go Down, Moses, described a black cemetery with “shards of pottery and broken bottles and old brick and other objects insignificant to sight but actually of a profound meaning and fatal to touch, which no white man could have read.”9

A potter’s field is a segregated burial site for poor, unknown, or unclaimed people, and were frequently used to bury free and enslaved Black people in the US through the twentieth century. Potter’s fields are hard to locate today. They were used only for short periods of time, had little or no signage, and only simple or rudimentary headstones, if any. These sites are highly significant, giving us a window into burial practices that “appear to have afforded African Americans an opportunity to develop African-American cultural practices in the New World based at least partially on African practices.”10

our death like our birth means something

a way to it, preparing a body all ours

ancestors returning again

this time only to themselves

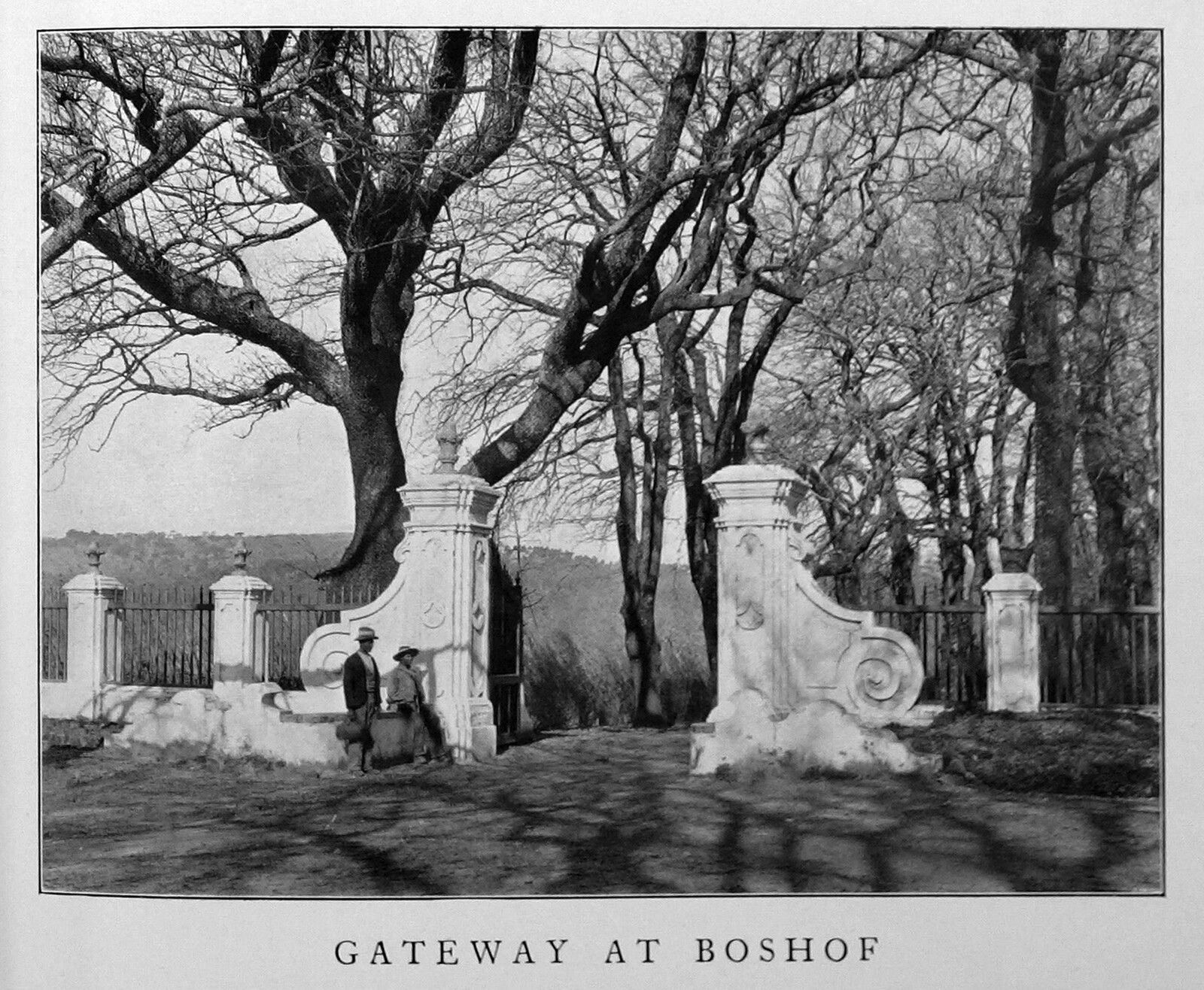

The potter’s field in Queen Lane, Philadelphia, was established in 1755; a playground and highrise building were constructed over the lot in the mid-twentieth century, both demolished in 2015 to make way for affordable housing. The preservation, marking, and contemporary program of the site is still being discussed between city officials, the Philadelphia Housing Authority, and the local community. Photo by the Aero Service Corporation, 1930.

The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission notes that “one of the more infamous Potter’s Fields was the ‘Stranger’s Burial Ground’ and ‘Negroes Ground,’” located in what is today called Washington Square in Philadelphia. There are, however, other notable potter’s fields in Philadelphia. In the northwest Philadelphia neighborhood Germantown lies a potter’s field that was established in 1755 “for all strangers, negroes, and mulattoes as die in any part of Germantown forever.” In 1921, however, a playground was built upon the field. As one long-time resident recalled: “Stones that we used for [baseball] bases were old grave stones.”11 Then, in 1955, the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) erected the Queen Lane Apartments over the Germantown potter’s field. In an area that had been redlined and where “white flight” was already underway, Queen Lane was built as a public housing project, a sixteen-story tower that originally housed 119 low-income “non-white” tenants. Like many other housing projects around the country, federal disinvestment and neglect led to significant maintenance and quality of life concerns, and its eventual demolition.

As PHA readied the site for demolition, redevelopment, and replacement in 2011, community and preservation groups demanded that the cemetery be preserved and memorialized. PHA worked to ensure that construction would only occur outside the boundaries of the potter’s field, and funded an archaeological investigation and preservation of the site. The investigation recovered approximately 6,000 artifacts described by the archaeologists who excavated the site as “mostly domestic in nature and included ceramics, glass, animal bones, architectural items and personal items such as smoking pipes and fragments of musical instruments.”12 Such findings are consistent with research findings of North American slave practices that included “the surface decoration of graves with ceramics and other objects [as] the most commonly recognized African-American material culture indicator of cemetery sites.”13

Shovel test pit 8 from the potter’s field, in the Phase I Archaeological Survey of the Queen Lane Apartments Project, May 2013. Source: Philadelphia Housing Authority, “Queen Lane Redevelopment,” 2011–ongoing.

Fifty-five new housing units were ultimately built on the former Queen Lane site in 2015. The 1921 playground, which was destroyed along with the tower, has yet to be rebuilt, contributing to the pre-existing lack of neighborhood play spaces for youth. As the community, city, and PHA work to find a new location for the playground and decide if and how the potter’s field should be used, the site is currently fenced off and marked by an engraved historical marker signaling its protected status. A powerful reclamation and reconfiguration of the relationship between a past, its relative present, and future, neighborhood youth today are regularly observed climbing the fence and playing baseball in the field while they wait for a dedicated area.14

In another part of Philadelphia, in an area to the south known today as Queen Village (no known relation to Queen Lane in Germantown), another potter’s field has laid buried for over a century beneath the active Weccacoe playground and community center. Weccacoe, a re-spelling of the original Lenape name for the neighborhood meaning “Pleasant Place,” was later colonized and renamed “New Sweden” and then “Southwark” by William Penn, becoming known as the city’s first suburb. The area would later become a haven and community for free Black people living in Philadelphia during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1820, nearly two-thirds of all Black families in Philadelphia were settled there. Queen Village had affordable housing, Black churches, and a strong sense of community. The potter’s field there was built in 1810 by Richard Allen, founder of the nearby Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, and is arguably one of the most significant African-American burial grounds in the country.

In 2008, historian Terry Buckalew discovered that a nineteenth-century graveyard, established by Richard Allen, the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, lay beneath the Weccacoe Playground in Queen Village, Philadelphia. More than 5,000 African Americans were laid to rest in Bethel Burying Ground, which was declared a National Historic Site in 2016. Exploratory archaeological works were undertaken in 2013 amid ongoing disputes about the maintenance of the ground and other public structures on the same site. Source: The Philadelphia Inquirer, photo by Akira Suwa, 2013.

After a period of thriving, urban redevelopment in the 1950s and 1960s resulted in the decline of Southwark and the eventual demolition of its homes and historic sites. The neighborhood was gentrified in the 1970s and 1980s, and by the early 1990s, re-branded by real estate developers as Queen Village after Queen Christina of Sweden.15 Today it is home to some of the highest income residents and property values in the city.

The Queen Village Potter’s Field was (re-)discovered in 2008 by local historian Terry Buckalew while doing research on the historical Black figure Octavius Catto. The reported 5,000 Black people who were buried beneath what is today a playground, a row of restrooms, tennis court, and community center stirred up conversations about the neglect of Black historical memory and sites in Philadelphia.16 Recognized as a historical landmark in 2013 and now known as the Bethel Burying Ground, a committee of residents have formed to plan for the future of the site that will both preserve its historical significance and find a new home for the community center and playground. There is also a website documenting the stories of some of the people buried there, including many prominent African-Americans, and public art projects dedicated to memorializing the site.17

They regulate space on top of communities

playgrounds on top of graves,

homes on top of landfills,

prisons on top of schools

distorting memory,

collapsing truth,

rendering uncertainty

The Queen Lane and Queen Village Potter’s Fields are tied by fate, one that places a tension between their respective communities’ re-memory and preservation of the past, their present needs for community planning and play space, and the future uses of those sites. According to linear time, these tensions might be rendered flat by what is chosen to be placed in their capsules, sealed off from the past and simultaneously crystallized into history upon its opening by the future. In a quantum time capsule, however, temporal tensions are expected and can be dynamic, open to influence and possibility. As cultural artifacts and reclaimed space-times emerge from the dirt, liberated from tombstones of buildings and concrete, potter’s fields are open air memorials that, once unburied, serve as quantum time capsules for Black cultural memory, space, and time. Simultaneously, those sacred grounds have been strong enough to hold housing, community spaces, and playgrounds and all the frequencies of joy and trauma that can be found within those communal space-times.

This don’t belong to you

This secret, from before

this hidden for the future

a quantum event, charting the memory,

the journey,

the way out

Quantum mapping the truth

View of excavations completed 1998–1999 at Palace Lands, Virginia, site 44WB90, where enslaved laborers had dwelling quarters from 1747 to 1769. Source: Maria Franklin, “Archaeology and Enslaved Life on Coke’s Plantation: An Early History of the Governor’s Palace Lands,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, August 2017.

Subfloor Pits and Slavery Time Capsules

Perhaps the most curious personal items from the sites were clock components: a clock winder and pewter key were found at Carter’s Grove (CG715B). A toy pewter pocket watch was also found in one of the pits at the late eighteenth-century Utopia quarter. It has been suggested that watches and clocks conferred power on those individuals who owned and understood them, although this power was generally that of the watch-owning planter over the enslaved.18

Subfloor pits are hollowed out spaces in the soil beneath the floorboards of a home. Archaeologist Patricia M. Samford studied over 100 subfloor pits at the archaeological sites of the homes, cabins, and quarters of enslaved Africans in Virginia.19 She found evidence that, beyond their apparent function as a storage place or “safety deposit boxes” for personal items or root vegetables, the subfloor pits may have also served as West African spiritual shrines between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. Artifacts found in these sites include: cowrie shells, seashells, colorful glass and clay beads, pieces of iron and copper, ceramic vessels, tobacco pipes, mirror glass, marbles, coins, bone combs, violin parts, and jaw harps, talisman, among other items and spiritual objects. Some objects contained etchings. Other objects were thought to have been divination tools.

Assortment of artifacts from Utopia IV, site 44JC787, James City County, Virginia. Excavation of site occupied in second half of eighteenth century, led by Garrett Fesler, 1993–1994. Source: Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery.

Some living spaces featured multiple pits. As one study notes: “sub-floor pits achieve their security function by making access to their contents time consuming, more likely to be publicly observed, and hence socially accountable,” which in turn “helped foster a greater sense of community among Chesapeake slaves.”20 The assemblages of artifacts found in subfloor pits are representations of rooted memories. They were ways of burying and storing memories in the face of psychological, physical, and mental warfare, such that they wouldn’t be lost in linear time and churned through the cogs of the Master’s Clock. Subfloor pits as quantum time capsules gave space and time for objects of specific value to exist outside the gaze of the captors, stored and lying in wait to return to the everyday.

Freedpeople’s Time Capsules

When a construction crew’s backhoe in 1991 uncovered a time capsule planted by former slaves, some of this mill city’s notions and symbols of the Old South began to crumble. The capsule, a three-inch-deep tin box, was nestled in a granite block in what had been a downtown department store. It contained an array of coins, biblical tracts, newspapers and personal artifacts, including an 1868 lapel pin that reads “U.S. Grant for President.”21

The Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History is a former confederate mansion known as the Last Capitol of the Confederacy due to its history as the temporary home of confederate President Jefferson Davis. It then became a whites-only library in the 1960s before becoming a museum in 1974. Despite being seen “as a symbol in Danville’s black community of segregation and the Old South,” the Museum houses a time capsule buried in 1870 by formerly enslaved Black people and members of the Society of True Friends of Charity. An exhibition of the time capsule in 1993 was used as an opportunity to try to unite the Black and white community of Danville and tell a fuller story of Black history in the town.22

From the perspective of the unnamed, captive laborers whose hands dug deep into the soil to build the United States’ infrastructure, we may uproot all kinds of hidden time capsules. For purposes of survival, enslaved Black people and post-liberation Black laborers—the original essential workers—came to understand the complexities of linear time better than others, learning to navigate white western timelines as our ancestors did the stars. They deftly traversed time and space to liberate one another long before the time of the Emancipation Proclamation, during the time of the Civil War, and after the time of so-called freedom. Time capsules were visions planted into the soil or cast into concrete cornerstones, like a safeguarded seed that will grow into a future they were never meant to reach, subverting the temporal domains of the past, their own present, and all possible futures where the time capsule is found.

When Reverend Christopher Rush laid the cornerstone of the First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in 1853, he placed in it a time capsule, a box that contained a Bible, a hymn book, and copies of two New York papers, The Tribune and The Sun. These were mementos for future New Yorkers. Rush, who escaped slavery and became the second ordained bishop of the AME Zion Church, also delivered the church’s first sermon.23

Reverend Christopher Rush had escaped slavery and ran away to New York in 1798. Unbeknownst to him, just two weeks prior to laying a time capsule in the cornerstone of the First African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church, the land on which the church sat had been condemned by eminent domain to make way for Central Park. The AME Zion Church had been instrumental in purchasing the land—known as Seneca Village—as a trustee in 1825. Where whites had refused to sell land to other Black people due to restrictive covenants, the land was purchased by two individual Black people, and then the church’s purchase. Seneca Village enabled other free Black people to buy land, build homes, and eventually build a thriving community where they enjoyed voting rights, quality education, religious freedom, refuge from racial violence and surveillance, and freedom to celebrate their cultural heritage. Such freedoms made the community a prime target for destruction by white politicians concerned with, among other things, liberated Black people gaining too much political power.24

Nearly twenty years after it was destroyed, Seneca Village had been mostly forgotten until a coffin containing the remains of a Black person surfaced in 1871 as contractors were building a new entrance to what was now called Central Park. The new entrance was in fact the site of the graveyard of the AME Zion Church.25 No further efforts were made to preserve or excavate the area until the early 2000s.

The lost time capsule cornerstone of Seneca Village’s AME Zion Church demonstrates how Western linear timelines are openly hostile to Black bodies, and openly deny us access to our own futures. It also demonstrates yet again how Black burial grounds serve as literal infrastructure to white progress, creating a wave of gentrification stretching forward and backward in time that touches Black people’s living space(-times) and invades our death space(-times). Even in death we are not allowed resting time or resting space.

Under the church

Time is a hymn

An offering of freedom

Monumental Time Capsules

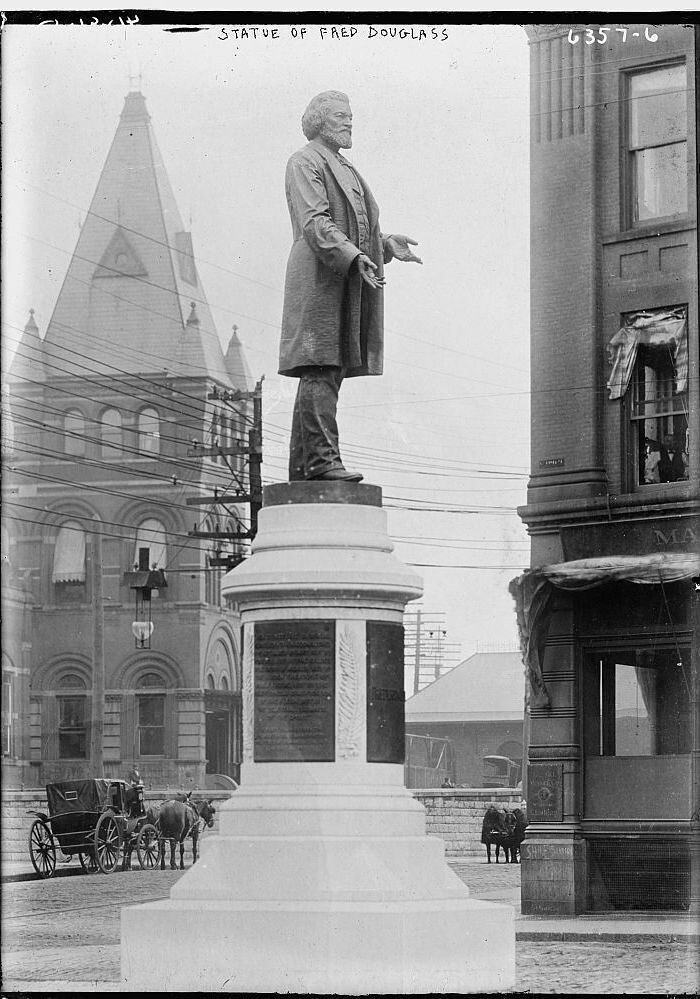

In 2019, as workers prepared to relocate a Frederick Douglass statue in Rochester, New York’s Highland Park to make way for a memorial plaza in his honor, a time capsule was discovered in a small cutout area inside the statue’s granite base. The statue—thought to be the first dedicated memorial of a Black person in the United States—was originally unveiled in 1899 in front of Grand Central Terminal in New York City after being commissioned by Black activist John W. Thomas, and was relocated to Highland Park in 1941. The beat-up tin box found inside the statue was filled with newspapers, books, roadmaps, city resolutions, and an 1898 calendar. Its contents also included newspapers from 1941, placed inside the capsule when it was originally moved, including a speech and newspapers.

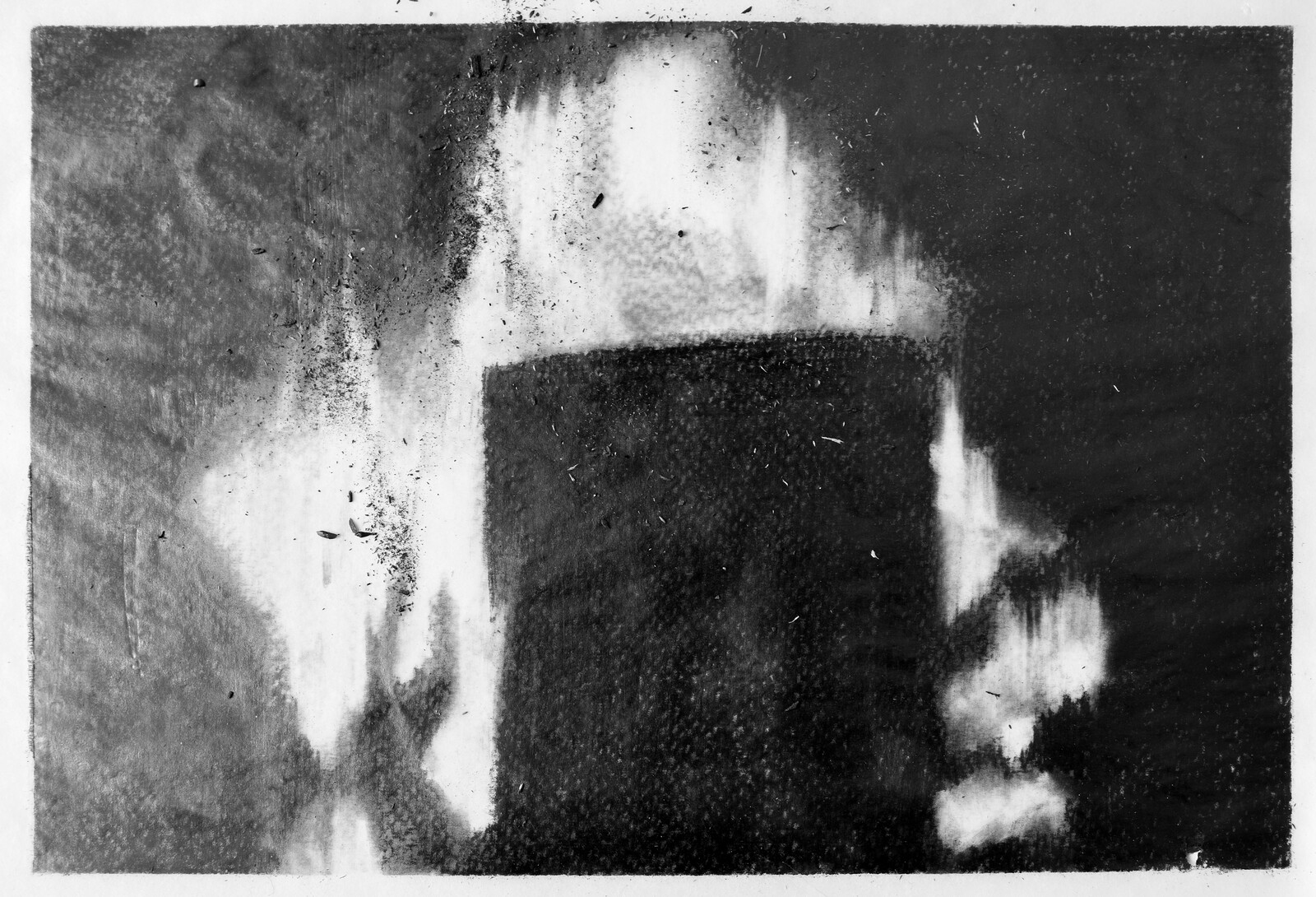

Most of the contents, including in the 1898 time capsule in Rochester were not salvageable individually due to moisture damage. Based on newspaper reports from the time when it was buried, the contents should include pamphlets by Susan B. Anthony, a map of Monroe County, a letter from Haiti talking about the donation of $1,000 to help build the Douglass statue, and more. Source: City of Rochester, October 2019.

While the time capsule’s documents were ultimately unsalvageable due to water damage, the true time capsule is the statue itself. It is an unburied quantum time capsule, open to revision, able to contain and generate new and old memories. Its monumental container occupies multiple time schemes and scales, and stretches into past, present and future sites of memory. The bronze representation of Douglass re-enacts an 1863 speech he gave in Rochester shortly after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. Ensnared in the statue-cum-capsule’s temporal web is 1863, 1898, 1899, 1941, 2019 and other dates and times. The statue also features a watch chain on Douglass’s body, a symbol of authority and power. Douglass is also surrounded by pillar sculptures of constellations, including the North Star, which served as the name of the newspaper Douglass published in Rochester and was a key temporal marker for enslaved Black people following the path to liberation.

In 2018, commemorating the 200th birthday of Douglass, thirteen replicas of the original statue were made and installed at key locations around the city as part of a history trail. Two of the replicas were vandalized in separate incidents, but both were eventually replaced. The 2020 replica was removed from its base and tossed into a gorge, either by anarchists—according to Trump—or according to the NAACP, in retaliation by white supremacists for the removal of confederate statues.

Monument to Frederick Douglass, Rochester, New York, 1900, published by Bain News Service. Source: Library of Congress.

SO THAT THE FUTURE MAY LEARN FROM THE PAST26

Preceding the Frederick Douglass time capsule discovery by four years was the recovery of a time capsule hidden in a cornerstone of the controversial confederate Vance Monument in Asheville, North Carolina during its restoration and repair. Constructed just two years before the Douglass monument in 1897, the sixty-five-foot granite block obelisk was constructed as a tribute to Civil War governor, senator, slave owner, and possible KKK Grand Dragon Zebulon Baird Vance.

The time capsule underneath the Vance Monument was crushed due to shifts in the monument since it was sealed in 1897. Archivists from the North Carolina State Archive were able to dry the contents and stabilize the pages. Source: The Urban News, May 2015.

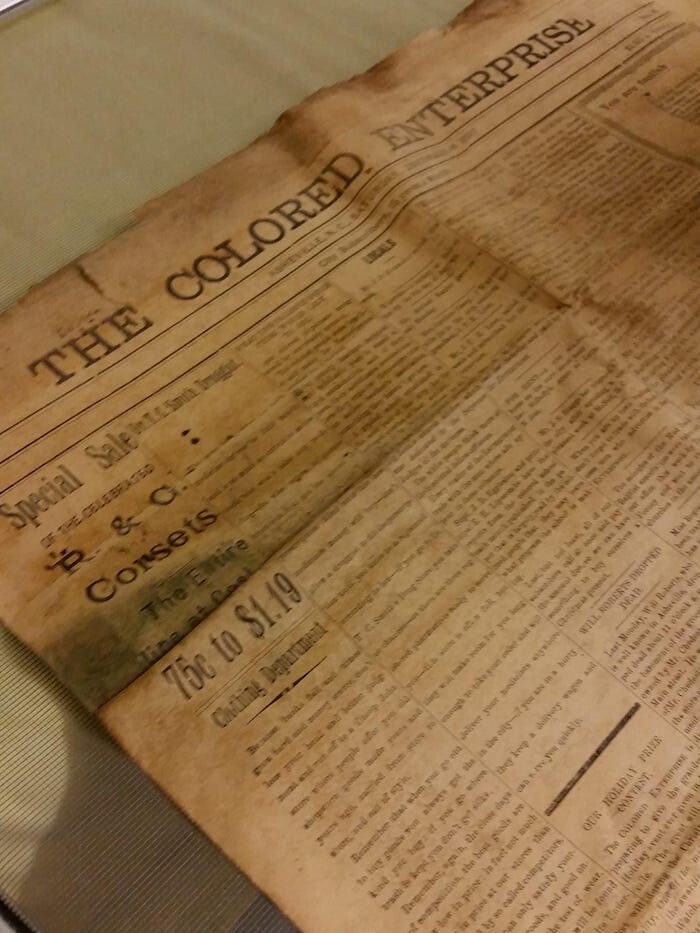

It is curious, then, that among the contents of the time capsule emerged a powerful piece of counterhistory: the only known copy of The Colored Enterprise, Black newspaper from the 1890s that ran for two years and, prior to the time capsule’s unearthing, had never been seen, only referenced in sources.

In March, a time capsule in the base of the Vance Monument yielded a voice from Asheville’s 1890s African-American community. The Colored Enterprise, a newspaper representing about a third of Asheville’s population in its day, lay concealed in a box at the base of the Vance Monument for more than a century. It was put there secretly by Masons in 1897, when the monument was dedicated, and recently discovered during restoration efforts. The time capsule contained the only known copy of The Colored Enterprise. Although scholars such as Dr. Darin Waters, a professor of history at UNC Asheville, have found references to it during their research, they’ve never actually seen a copy.27

Among the contents of the 1897 time capsule at the base of the Vance Monument was the only known edition of The Colored Enterprise, a historic newspaper for Asheville’s African-American community, published and edited by Thomas Leatherwood from 1896 to 1898. Source: Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina/The Citizen-Times.

Local archivists shared that the capsule contents were put together by the local Freemasons, who did not specify an opening date. When a current member of the Freemason lodge who buried the capsule was interviewed, he observed that “the time capsule was probably intended to represent the entire community,” and that while “historically, people have thought of Masons as a white, male organization … the only thing Masons ask of a man is belief in a deity.”28 Vance belonged to this same lodge.

The time capsule in the Vance Monument also included a bound copy of the Masonic Code, a symbol of the Masons who secretly installed the capsule when they laid the cornerstone for the obelisk in Pack Square, Asheville in 1897. Source: Angeli Wright, The Citizen-Times.

As the monument was being restored and the time capsule recovered, a petition signed by over 2,000 local community members called for a marker honoring Black people to be erected nearby. The controversy over the monument’s presence and symbolism spilled over into 2020 and caught new life after the murder of George Floyd and the racial uprisings that followed, in which the statue was called to be removed, protestors and activists projected art and messages on the monument, and created art in the streets surrounding it. Asheville City Council overwhelmingly voted to remove the monument in early 2021, and debates continue on what to do with the monument or its granite remains once dismantled.

The Vance and Douglass monuments are both relics needing to be troubled in order to disrupt their status as frozen testaments to one time or singularity, and instead reveal the time capsules within. These time capsules function as a temporal hack, one that fundamentally alters future conditions and allows Black people to trouble and leave their mark on it, planting ourselves where we have otherwise been erased. Situating these monuments, or their embedded time vessels, as quantum time capsules also requires us to ask: what information can the past glean from the future, and what can the future transmit back to the past?

Time Capsule Contents

Particular categories of material have been favored in surface assemblages. The color white, evident in ceramics, shells, and pebbles, is of importance. Association with water is also evident, which took the form of water jugs, marine shells, or mirrors which served as a metaphor for water. Clocks are a 20th-century addition, and may be set either at 12 o’clock to wake the dead on Judgment Day, or at the time of the deceased’s death.29

● 5 phonograph records

● 3 hot combs

● 6 pair bamboo earrings, various sizes

● 3 records in album

● 5 records (miscellaneous)

● phonograph records in 2 boxes – History of Mines – 37 10″ records, 2 12″ records

The Macon Housing authority envelope will have to be dried out before what was written inside on a document can be read. And an answering machine recorder will be needed to get the audio on the tape.30

● 1 bottle of Hennessy (about one quart)

● 1 plastic ash tray

● 1 painting of white Jesus

● 1 painting of Black Jesus

● 1 hood hair dryer

● 10 copies of Ebony magazine, various editions

● 10 copies of Jet magazine, various editions

● 1 vanity make-up mirror with light

● 1 plastic savings bank

● 3 plastic afro picks

● 1 plastic display case for watch

● 1 gold plated cigarette holder

● 2 copies of a leather-bound King James Bible

If historical records are accurate, she said, the contents include two leaflets from Susan B. Anthony, who was alive at the time of the monument’s original dedication; a copy of the Declaration of Sentiments, an 1848 document penned by Elizabeth Cady Stanton demanding equality for women; a road map of Monroe County; the 1856 book Slavery Unmasked; and a letter from the government of Haiti, which contributed $1,000 (around $31,000 in today’s dollars) toward the statue’s cost.31

● Molded glass candy dish, various colors

● Molded glass shaker and tumbler, blue

● Clay tobacco pipe bowls and stems – Feature 10

● 4 clay marbles, various sizes

● 1 set of scales (hand)

● 2 curling irons

● 1 bottle of holding gel

● 1 Regen’s cigarette lighter

● 1 Ingraham wrist watch (woman’s)

Unearthed recently by contractors working on a housing development at the site, the time capsule—actually a weathered tin box about the size of a loaf of bread—contains newspapers, a Rotary Club handbook, the school board’s 1924 annual report and a handful of pennies dating from 1901 to 1920.32

● 1 Monroe calculator

● 5 handkerchiefs, and silk scarves

● 1 Yankee screwdriver, 1 screwdriver and special screws

● 12 packages Rayon-Component parts and displays, 1 watt-hour meter, 1 tube rayon thread, 1 set of 6 radio tubes

● 1 toy pistol, 1 pinball game, 1 toy airplane

● 1 Negro doll, 1 toy flying gyro, 1 wrecker

● 1 toy greyhound bus, 1 tractor, 2 dolls (white), 1 1-one Ranger, 1 ambulance

● 1 Donald Duck, 1 set toy tools, 1 toy tank, 1 pacifier, 1 bubble pipe, 1 rattle

● 1 toy equestrian, 18 toy soldiers, 12 toy civilians, 1 toy cannon, 2 muses, 1 anti-aircraft gun, 1 set samples of better ware

● 1 blotter, 1 inkwell (sealed)

● 1 sample textile (cotton), 1 sample of rayon cloth

● 1 transcription (King Edward VIII)

● 1 package Masonite (sealed)

● 1 denture (Lipper), 1 box samples of Micarta (sealed), 1 box samples of carpets, 1 crystalite, 10 rings

● 1 plastic flute

● 1 Black dollhead

The time capsule contained the only known copy of The Colored Enterprise. Although scholars such as Dr. Darin Waters, a professor of history at UNC Asheville, have found references to it during their research, they’ve never actually seen a copy.33

● 1 toy whistle, 1 golfball, 1 cake of soap

● 1 cover for milk bottle, 1 plastic knife, fork and spoon, 1 salad fork and spoon

● 1 carving knife and fork, 1 rule, 1 screwdriver

● 1 grapefruit corer, 1 potato masher, 1 ladle, 1 spoon, 1 pancake turner

● 1 asbestos mat, 1 red china plate

● 1 box of crayons

arrangements of a vast array of articles including ceramics, glassware, clocks, lamps, seashells, spoons, doll heads, lightbulbs, flashlights, false teeth, eyeglasses, cigar boxes, piggy banks, gun locks, razors, knives, tin cans, marbles, pebbles, and at least one example of a ceramic toilet tank.34

● 1 toy automobile, 1 toy stagecoach, 1 image of Buddha (incense burner)

● 1 small china plate, 1 small china bowl, 1 glass rolling pin

● 1 package rayon chemicals

● 1 piece sheet music

To insure Americans who live in the 21st Century that Negroes made valuable contributions to American life, a committee working toward the memorialization of the late Dr. James E. Shepard, Founder of North Carolina College, will embalm records of Negro life—films, newspapers, maps, clip pings. news article and similar documents—at the base of the proposed monument of the educator.

The first such “time capsule” of present day Negro-life will include activities of the Urban League, NAACP, fraternal and religious organizations, cults, women’s clubs, newspapers, the National Business League, educational societies, and leading insurance companies.35

Chelsea Beimfohr and Mary Grace Shaw, “Contents of ‘mystery safe’ leave people asking more questions,” 13WMAZ, July 10, 2017, ➝.

William E. Jarvis, Time Capsules: A Cultural History (Jefferson: McFarland & Co., 2003), 25.

Jeremy Rifkin, Time Wars (New York: H. Holt, 1986).

Nick Yablon, Remembrance of Things Present: The Invention of the Time Capsule (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2019).

Kate Giammarise, “Library gets 1930s relics from project’s time capsule,” Toledo Blade, February 21, 2013, ➝.

Ella P. Stewart and Gary Franklin, “‘A Snapshot of the Negro in Toledo pre-1930s’ by Ella P. Stewart,” Journey, August 24, 2016, ➝.

Ibid.

John D. Combes, “Ethnography, Archaeology, and Burial Practices among Coastal South Carolina Blacks,” Conference on Historic Sites Archaeology Papers 7 (1972): 54, quoted in Ross W. Jamieson, “Material Culture and Social Death: African-American Burial Practices,” Historical Archaeology 29, no. 4 (1995): 39–58.

William Faulkner, Go Down, Moses (New York: Random House, 1942), 135, quoted in Jamieson, “Material Culture and Social Death,” 50.

Jamieson, “Material Culture and Social Death,” 39.

Cherri Gregg, “Queen Lane Apartments Gone, But History Remains,” CBS Philly, September 13, 2014, ➝.

“Queen Lane Archaeology,” Philadelphia Archaeological Forum, ➝.

Jamieson, “Material Culture and Social Death,” 50.

Jason Laughlin, “In Germantown, a housing development, a Colonial graveyard, and the playground that wasn’t,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 27, 2020, ➝.

Steve Sitarski, “History of Queen Village,” Queen Village Neighborhood Association, May 18, 2011, ➝.

Bethel Burying Ground Project, ➝.

Patricia M. Samford, “Power Runs in Many Channels: Subfloor Pits and West African Based Spiritual Traditions in Colonial Virginia” (PhD diss., University of North Carolina, 2000), ➝.

Ibid.

“A Housing Revolution,” Monticello, ➝.

Bonnie V. Winston, “Time Capsule’s Treasures at Home in Museum Buried by Former Slaves,” Greensboro News & Record, April 22, 1993, ➝.

Ibid.

Leslie M. Alexander, African or American? Black Identity and Political Activism in New York City, 1784–1861 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008).

Heather Gilligan, “An entire Manhattan village.”

Inscription on the 2015 rededication plaque in front of the Vance Monument.

Emily Patrick, “Black history emerges from 1897 time capsule,” Citizen Times, June 3, 2015, ➝.

Emily Patrick, “City unearths time capsule beneath Vance Monument,” Citizen Times, March 31, 2015, ➝.

Jamieson, “Material Culture and Social Death,” 51.

Stanley Dunlap, “No guess came close to what was buried inside a Tindall Heights safe,” Macon Telegraph, July 10, 2017, ➝.

Marcia Greenwood, “Can Frederick Douglass time-capsule contents be saved?” Democrat and Chronicle, October 24, 2019, ➝.

Kristin Harty Barkley, “Penn Ave. time capsule unearthed,” Cumberland Times-News, October 26, 2011, ➝.

Patrick, “Black history emerges from 1897 time capsule.”

Jamieson, “Material Culture and Social Death,” 50.

“Time Capsule To be Placed In Statue Of Dr. James Shepard,” The Carolina Times, October 1, 1949, ➝.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.