Sigidm hanaa’na̱x, Smgyigyit, Łagyigyet, ada txa’nii gyeda galts’ap.

Sm Łoodm ‘Nüüsm di waayu. Mootgm Goot di nooyu.

La̱xsgyiik di pdeegu. Gispaxlo’ots di wil ‘naat’ału. Ts’msyen ‘nüüyu.

Tak’waan di wil manyaa p’asu ada ‘waatgu.

Laxyuubm Ts’msyen di wil dzog̱u, siwaadida Terrace, British Columbia a Ḵ’amksiwaamx.

Hasag̱u nm t’oyaxsm wil amuksm a goo ła dm mału da kw’asm.

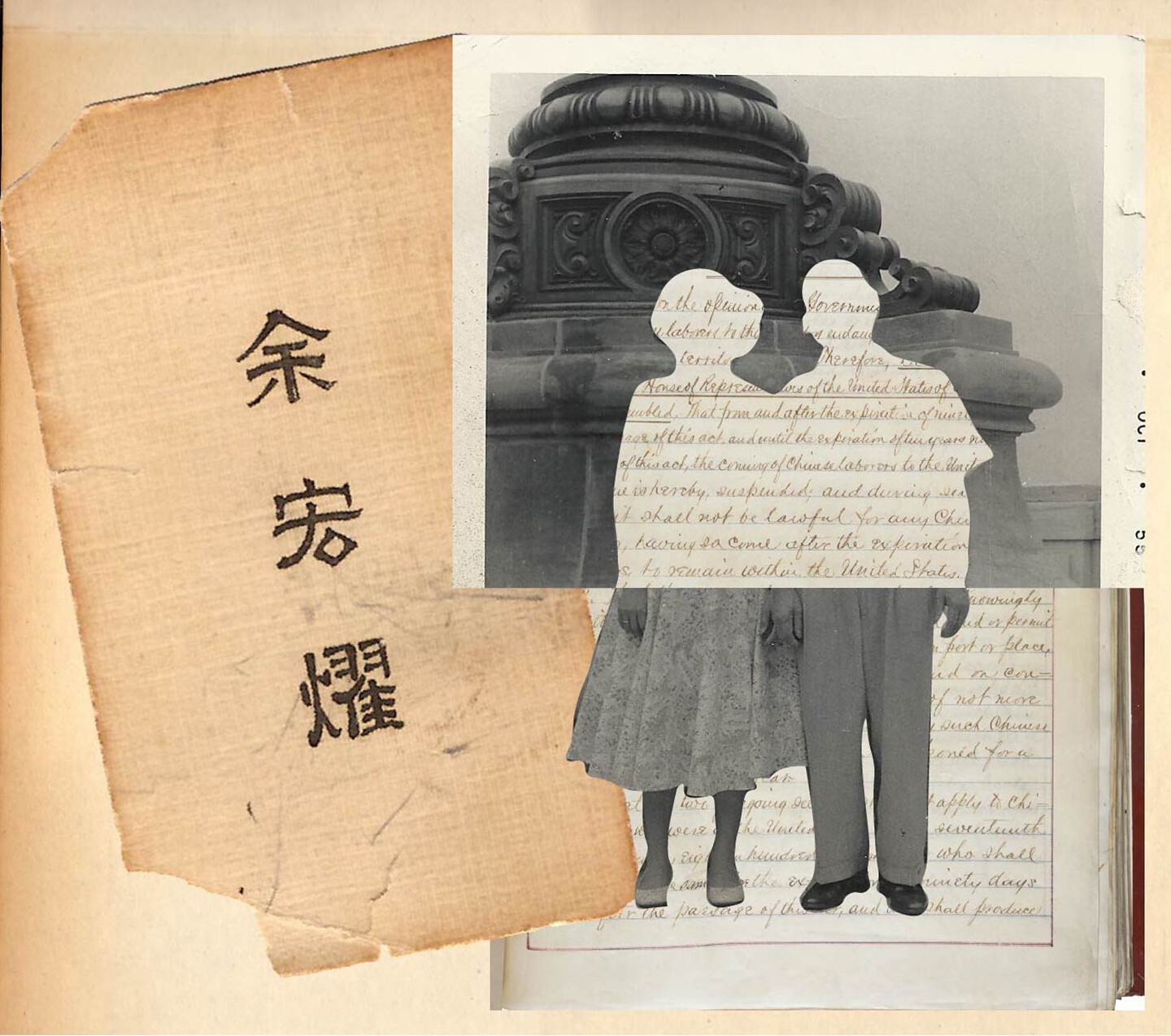

In my language, Sm’algya̱x, I have followed the protocol of my people by acknowledging our matriarchs, chiefs, and ancestors. I introduced myself by the matrilineal line that defines my identity as a Tsimshian woman from Metlakatla, Alaska, who is living in the area of our traditional territory known by its colonial name—Terrace, British Columbia (BC). I have also expressed my gratitude to you, the reader, for your time and attention. I here write as a recent first-time biological mother, wife, witness, and active participant in ceremonies dedicated to the missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, men, boys, and 2SLGBTQ held in Terrace in 2020.1 These ceremonies culminated with my husband Goolth Ts’imilix, Nisga’a/Tsimshian artist and carver Mike Dangeli, raising a twenty-foot totem pole on September 5, 2020 dedicated to the memory of these loved ones, in commemoration of their families, and to generate greater awareness about this on-going genocide.

Photo of author at event.

As Indigenous artists and scholars, the first academic training that Goolth Ts’imilix and I received was from our elders, who taught us to how to honorably carry the responsibilities necessary to make impactful and positive contributions to our people’s cultural resurgence. As such, we have always engaged with the concept of survivance, long before we knew it by name as expressed in the work of Anishinaabe cultural theorist Gerald Vizenor. His articulation of survivance, however, resonates most deeply with our lived-experience maintaining and revitalizing our peoples language, visual and performing art practices, and other aspects vital to our ancient and contemporary ways of being and knowing that were nearly lost during our cultural oppression.2

This began to take on new meanings for us when the first wave of COVID hit in the midst of our final preparations for the totem pole raising. We, like many Indigenous cultural leaders, started to contemplate the new form and strategies of survivance we would need to embody during the global pandemic. Questions related to Vizenor’s statement that, “survivance in the sense of native survivance, is more than survival, more than endurance, more than mere response: the stories of survivance are an active presence,” ran circles through our anxiety-stricken minds.3 We asked ourselves how, during COVID, do we persist with this much needed ceremony and monument honoring the loved ones whose “active presence” was heinously taken from the lives of their families, friends, and communities?

The statistics are horrifying. There have been more than 4,000 Indigenous women and girls murdered or who have gone missing in the past forty years. That is about 133 of us per year, or three a week.4 Most national statistics are considered to be gravely underestimated by Indigenous communities. It is even more difficult to find accurate statistics on the men, boys, and 2SLGBTQ who have been murdered or gone missing. Over many long late-night discussions while our infant son slept, Goolth Ts’imilix and I thought through these questions: How do we safely assert our active presence in our territory and on this issue when being in each other’s physical presence is the cause of viral spread? What can we do to stop pandemic restrictions from causing further erasure of genocide and its devastating effects on Indigenous people globally? We brought these questions, and many more, into our conversations with elders and other organizers of the ceremony.

The main organizers of the totem pole project were elders Basa̱x̱ (Nisga’a First Nations matriarch Arlene Roberts), Head of the Indian Residential Survivors Society Office in Terrace, BC, and Gladys Radek (Gitxsan/Wet’suwet’en First Nations), a prominent Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) activist.5 Radek has worked closely with the families of MMIWG for over a decade and was called to testify in Canada’s National Inquiry into this issue.6 The catalyst for Radek’s focus on MMIWG was the disappearance of her niece, Tamara Lynn Chippman, from Terrace, BC over 15 years ago. Since then, Radek has organized an annual 350-kilometer awareness walk along Terrace’s main artery, Highway 16, in Tamara’s memory and to bring awareness to all those who have gone missing along this interstate.7 Highway 16 is known as the Highway of Tears, because of the high number of people who have gone missing while traveling along this route.

The totem pole project was Radek’s longtime dream. She states: “This is kind of closing the circle for me from the walks. I wanted a space where families could go to find a bit of healing, a bit of peace, and a little bit of honoring of their loved ones.”8 The Highway of Tears runs from Prince George, BC, north through many Indigenous communities, ending in Prince Rupert. Radek and Basa̱x̱ worked diligently to secure authorization and build a partnership with the Ministry of BC Highways for the totem pole to be raised along the Highway of Tears. According to the Aboriginal People’s Network Television News, since the 1970s at least fifty people have gone missing over the 725 kilometer stretch of the highway where the totem pole procession marched.9 The ceremony and the totem pole itself are bold statements of active presence over tremendous and heartbreaking absences.

The strategies of survivance that emerged from discussions with Radek and Basa̱x̱ of how to proceed safely during the pandemic included limiting the number of participants in the totem pole raising and doing all we could to ensure that each person wore masks and followed social-distancing. These parameters are now well-known and practiced at all public events. What made these regulations different for us as Indigenous people from the Northwest Coast, however, is that the ceremony central to our culture—most commonly known as potlatch—depends upon the physical presence of witnesses and the many important roles they have in validating the proceedings of the ceremony.10 Witnessing requires attentive listening and observing with the objective of remembering in great detail and responding in ways that recall the most important aspects of what occurred. Through their words and memory, they affirm the ceremony and inscribe it into our oral history. Witnesses are compensated for carrying out their responsibilities through gift-giving and feasting. Following these protocols during COVID called for more consideration and care as the health and welfare of all involved was at stake.

Family members of the missing and murdered from across Canada, who were passionate about travelling to witness the totem pole raising in order to honor the memories their loved ones, made the decision to cancel their plans to prevent any chances of spreading the disease. Goolth Tsimilx put forward the concept of hosting a “virtual potlatch” that would consist of a combination of live-stream and pre-recorded videos to ensure that the families, and the many others who wished to witness the ceremony, had the opportunity to see it for themselves. He asked Indigenous dance groups from Nations across the US and Canada to submit videos of the songs and dances they wished to share at the ceremony. The event was live-streamed by Canadian First Nations Radio (CFNR), and it garnered a staggering 350,000 viewers from Canada, the US, Australia, and New Zealand.11 For their role as witnesses, Goolth Tsimilx and I composed a song commemorating this event and publicly gifted it to everyone as payment for their roles as witnesses.12

This totem pole is the twenty-sixth carved and raised by Goolth Tsimilx. His totem poles are normally raised by hand in the tradition of our people, where groups of men and women work together to carry it to the site and then raise it using a series of ropes and wooden supports. Another strategy devised to inhibit the spread of COVID was to forgo the traditional raising and instead transport the totem pole with a flatbed truck and raise it with a crane. Once at the site of the raising, the totem pole was cleansed using sg̱a̱n smg̱an (cedar bow) and water from our sacred K’syen (Skeen River).

When the pole was in place, Sm’oogyit ‘Wii Dildaalda (Hereditary Chief and Elected Band Chief Don Roberts) spoke about the history of his people as it relates to the killer whale and robin figures on the totem pole. The bottom figure is the killer whale crest of the traditional owners and caretakers of the territory in which the totem pole stands, the Gisputwada clan of the House of Lagaax. The top figure is a robin, a crest representing all of the people of Kitsumkalum. Goolth Tsimilx then went over the symbolism of each figure starting with the bottom and most important—the killer whale. Above that is a central figure of a woman wearing a red dress, her face painted with a red hand across her mouth, both of which have come to symbolize the MMIWG movement.13 The woman is surround by children of different ages, Indigenous clans, and genders, including one draped in a Pride Flag representing two-spirited people. Each one represents the children left parentless and the parents who lost their children.

The figure above that is a matriarch symbolizing the important role that Indigenous mothers, grandmothers, and aunties play in the lives of their families and communities. The matriarch also asserts that the Tsimshian, and other Indigenous people from this area, are defined by matrilineal descent. She wears a ceremonial robe that is inlaid with mirrors instead of buttons, which are traditional in this area. The mirrors reference the mirrored shields used by the Water Protectors at the Dakota Access Pipeline. These shield were created to reflect back to law enforcement the egregiousness of the actions as they attacked those who were peacefully demonstrating.14 Goolth Tsimilx’s decision to inlay mirrors and imbue them with this meaning is based on the prominent belief among First Nations communities that law enforcement is implicated in this on-going genocide through their complacency, misconduct, and misdirected efforts that work against Indigenous people rather than with and for us. The mirrors also declare that we learn from each other’s battles. Our survivance is predicated on our ability to do so.

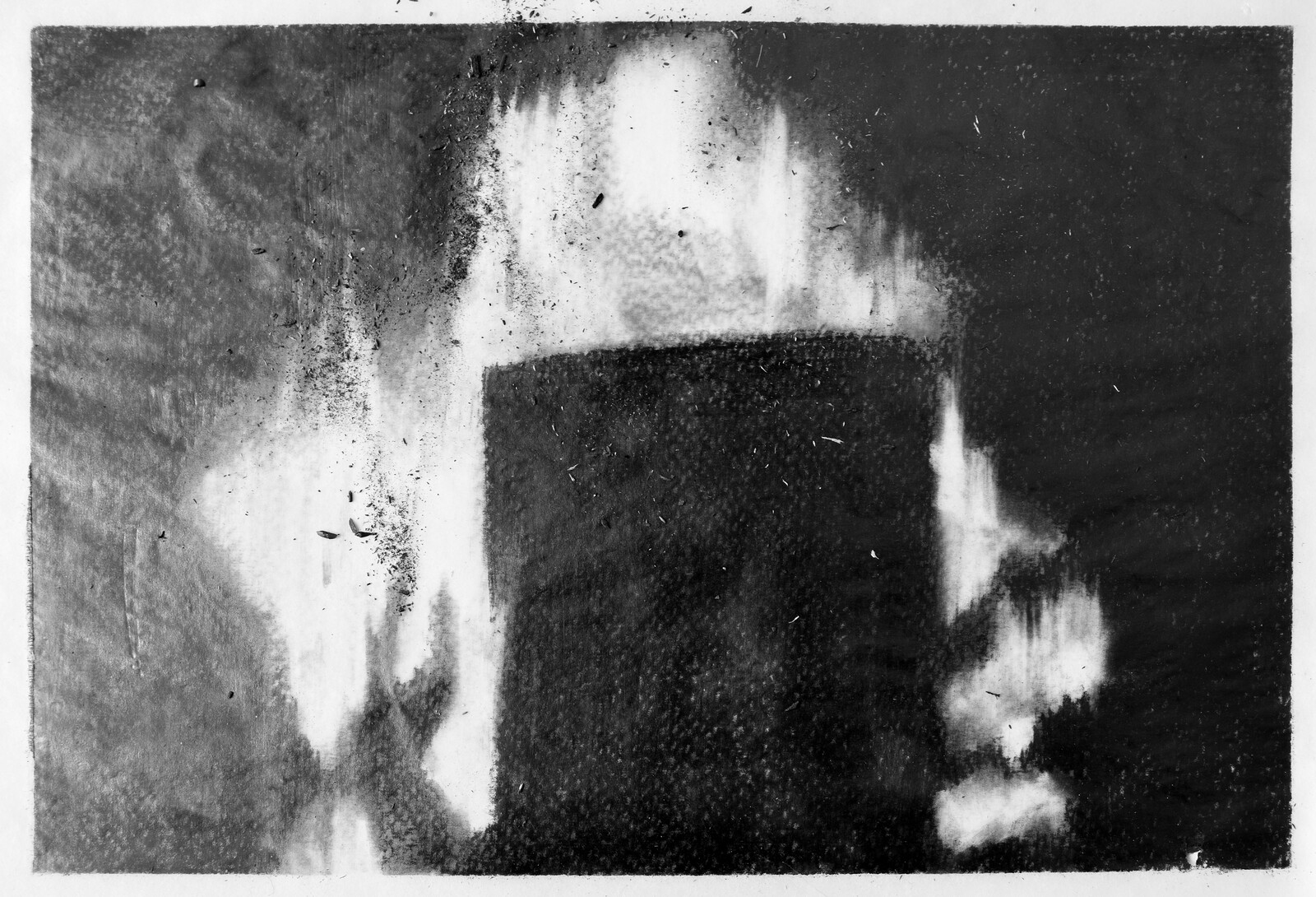

Mike Dangeli and Duane Grant singing at the closing of the ceremony.

There were many other speakers and parts to the totem pole raising ceremony. The blessing ceremony using eagle down had particularly transformative power. P’lk’wa̱ (eagle down) for our people is one of the highest forms for supernatural power, as it travels with the eagle as close to Sm’oogyit La̱xha (Chief of the Sky) as possible. When distributed through movement and song in ceremony, it becomes sign of peace and blesses everything and everyone it lands upon. Compared to her state earlier that day, tearfully witnessing the totem pole raising while holding a photo of her dear niece Tamara, Radek’s strength was renewed by the p’lk’wa̱ as the final stage of her dream became a reality. The hope of all those involved in this project is that visiting the totem pole will do the same for all of the families of the missing and murdered in their own healing journeys.

I gave birth to my first biological child, Hayetsk Dangeli, just ten months prior to the totem pole raising. Every day since March 2020, I’ve grappled with how Goolth Tsimilx and I are to carry the responsibility of passing down our language, songs, dances, foods, and ceremonies to our son when the pandemic keep us away from relatives who must also contribute to his upbringing, knowledge, and experiences. When Hayetsk was born, Goolth Tsimilx, and our adult sons Michael (27) and Nick Dangeli (22), were halfway finished carving the totem pole. Before he could walk, Hayetsk and I visited his Nagwaadii (Daddy) nearly every day while he finished carving the pole on his own. He loved crawling through the woodchips, taking the bigger blocks of red cedar and hitting them together, and running his hands over the features of the figures when Goolth Tsimilx and I held him over it. With his love for the totem pole, we knew he had to be there for its raising.

With the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) discouraging the use of masks on children under two, Hayetsk witnessed the ceremonies in his stroller using a rain shield for COVID protection. My concerns that the set-up we created for his safety would inhibit him from truly learning from and experiencing the totem pole raising dissipated when Hayetsk picked up his drum and started following along with the song sung by his Nagwaadii (Daddy). Goolth Tsimilx and I sing and drum with him daily at home. Witnessing Hayetsk drum on his own during this ceremony spoke volumes about his sense of knowing and belonging to our people and ceremonies, as well as his promising future for continuing this important work in his own way. These experiences, will no doubt, be one of the many stories of survivance Hayetsk will tell his children and grandchildren.

2S, which stands for Two-Spirit, is placed at the beginning of LGBTQ to emphasize and prioritize Indigenous ways of recognizing the gender spectrum.

In 1884 the Canadian Government revised the Indian Act in order to outlaw potlatching as well as other First Nations ceremonies throughout the country. Missionaries, government agents, and other colonial figures viewed potlatch as a hindrance to assimilating First Nations people into Euro-Canadian society. Despite these efforts by the government, missionaries, and the Indian residential school system to enact our cultural oppression, First Nations people continued their ceremonies in secret throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Few cases were successfully prosecuted in court. The most well-known incident took place at a large potlatch hosted by ‘Na̱mg̱is Chief Dan Cranmer at Village Island in 1921. Forty-five were arrested, twenty-two of whom were offered a lesser sentence in exchange for their ceremonial beings, which included masks and regalia and the rest were sent to prison. The potlatch ban was dropped in 1951. Aaron Glass, “The Thin Edge of the Wedge: Dancing Around the Potlatch Ban, 1922–951,” in Right to Dancing/Dancing for Rights, ed. Naomi Jackson (Alberta: Banff Centre Press, 2004), 56–57, 61, 79.

Gerald Vizenor, Fugitive Poses: Native American Scenes of Absence and Presence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 15.

Brandi Morin, “Indigenous women are preyed on at horrifying rates. I was one of them,” The Guardian, September 7, 2020, ➝.

Other organizers include Marc Snelling and Wanda Good. Funding was provided by Women and Gender Equality Canada, with additional donations by the Indian Residential School Survivors Society, and B.C.’s Ministry of Transportation.

See Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019, ➝.

For more on Gladys Radek and her powerful activism, see: “A Conversation with Indigenous Activist Gladys Radek,” Voice of Witness, March 5, 2020, ➝; Charlotte Morritt-Jacobs, “The journey of Gladys Radek and her fight for human rights,” APTN National News, June 4, 2019, ➝; Chantelle Bellrichard, “‘The genocide cannot continue’ says longtime MMIWG advocate Gladys Radek,” CBC News, June 4, 2019, ➝; Christine McFarlane, “Gladys Radek: A woman on a mission,” Aboriginal Multi-Media Society: Raven’s Eye, 2011, ➝.

Jake Wray, “Highway of Tears memorial totem pole to be raised in northern B.C.,” The Chilliwack Progress, July 22, 2020, ➝.

Lee Wilson, “Memorial pole raised on Highway of Tears in B.C. for families,” APTN National News, September 15, 2020, ➝.

Among Northwest Coast First Nations people, potlatches are ceremonial events where hereditary privileges, their associated histories, and kinship are asserted through oratory, songs, dances, and in some cases totem pole raisings, and validated through feasting and the distribution of gifts to the witnesses.

The livestream and dance group performances are archived together on the same page on CFNR’s website. See MMIWG/2SLGBTQ, “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls,” CFNR-FM, ➝.

Among our people as well as other Indigenous people along the Northwest Coast, songs and dances are property. The phrase “gifting a song” is commonly used to refer to the act of granting another person the right to its use. The rights to perform songs are inherited through family lines or gifted by a person who has the rights to grant permission. Ownership of songs and dances can be held individually, collectively, or both. It is a shared protocol that the ownership and/or permission is stated in the oratory before the song is performed. When the song is an inherited privilege, ownership is most often articulated in terms of belonging (i.e. “this song belongs to…”). These types of song are sometimes referred to as “ancestral songs.” When the right to perform a song is received through gifting, however, the introduction of its ownership and permission is usually articulated along the lines of: “This song belongs to ___; it was gifted to ___ from ___.” The composer is also acknowledged in the introduction, as an important part of the song’s history. Thus the history of this totem pole will be carried forward in its retelling as a part of the singing of this song.

For more information on the symbolism of the red dress, see: Jaime Black, The REDress Project, 2011–present, ➝. For information on the meaning of the red handprint across the mouth, see: Rhiannon Johnson, “Widespread use of red handprints to represent MMIWG sparks debate among advocates,” CBC News, March 9, 2020, ➝.

For more information on the creation and use of the mirrored shields that Water Protectors used during the demonstrations against the Dakota Access Pipeline, see: Carolina A. Miranda, “Q&A: The artist who made protesters’ mirrored shields says the ‘struggle porn’ media miss point of Standing Rock,” Los Angeles Times, January 12, 2017, ➝.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.