It was the summer of 1989.

Residents of Fergana, one of the largest cities in what was then the Uzbek SSR, brought carefully picked garden fruits, vegetables, and herbs to the bazaar, their sweet-spicy smells beckoning. Cats crawled around, trying to get any kind of attention. Locals and tourists alike flocked to the square.

“How much are these strawberries?” someone asked.

Suddenly, the trading routine was interrupted by a woman’s scream. A quarrel among grocery stalls turned into a terrible slaughter, and later into pogroms that spread to other cities. Fierce inter-ethnic hatred lasted with incredible cruelty for a year.

Soviet authorities noted that these terrible events started when one Turkish Meskhetian man insulted an Uzbek saleswoman and threw a plate of strawberries at her, scattering them all over the counter and onto the ground. Some Uzbek men stood up for this woman, and after an exchange of words, the quarrel turned into a fight. The pogroms that followed, which threatened the smaller ethnic group, Meskhetian Turks, resorted to horrific violence.1 Uzbeks killed Meskhetian Turks with pitchforks, cut off their heads, and burned them alive. The same documents say that women were found raped, their stomachs cut open, and their entrails turned out. Anger grew and expanded. As a result, the character of cities changed: where before one might have felt safe became scary and dangerous. Everyday routine became full of hatred, fear, and the pain of others. Nothing remained except the crushed strawberries accidentally trampled by those who tried to hide.

It was the same summer of 1989.

Miners came out onto the main square in Donetsk. Half-dressed under the blazing sun, they were on strike, demanding better labor rights. Back then, my father was a miner. He dreamed of building an independent adult life with his wife, my mother. At the time of the protests, they already had an almost two-year-old daughter, and my mother was pregnant with me. By the time I was born, the strikes grew and covered the whole of Ukraine. Miners from the Luhansk to Lviv Oblasts declared that it was time to change.

Although the Soviet Union officially ended in 1991, its collapse began earlier. Rapid social changes and state reconstruction already started after the Chornobyl disaster in 1986. But 1989 was the year of mass environmental protests in Ukrainian SSR, as well as miners’ strikes that began voicing the demand for Ukrainian independence. 1989 was also the year that Crimean Tatars (Qırımtatarlar) finally returned home, primarily from Uzbek SSR, after being forcibly deported from Crimea in 1944.2 This long-awaited return was not easy; after returning, Crimean Tatars found themselves without the right to live or work on their own land. In 1989, one of the largest protests of Crimean Tatars, including a hunger strike, took place near Simferopol, demanding rights to own property and build apartments.

My relationship to the state I was born in, which collapsed just a few years later, is mediated through (re)construction. Yet these processes of reconstruction are not specifically local, or at least need to be understood within a much wider geography and framework that encompass the fall of the Berlin Wall, the reconstruction of Europe, and the Balkan wars.

I look to Europe in 1989 while thinking of the future of Ukraine and possible scenarios of reconstruction. My contemporary reality and foreseeable future coincides with my background and knowledge of 1989. What I see is that returning home is critical, and that reconstruction is not only of physical houses and cities, but of justice itself. I look to the story of the Crimean Tatars in particular to try and understand the pain with which they lived with for almost fifty years with the desire of returning home. While their experiences cannot be equated to that of anyone else who has been similarly displaced or exiled, their story is important to remember, given that under the oppression of totalitarian states, many do not survive.

***

It was the summer of 1989.

The young Crimean Tatar academic Refat Galimov, whose family was deported along with many other Crimean Tatars to Fergana in 1945, witnessed the pogrom from the window of a local cafe where he met with his students, some of whom were Meskhetian Turks. When the furious crowd started approaching the cafe, the students decided to run, but Galimov stayed. He looked at his young students, who had disappeared behind a neighboring building, with sadness and pity, for he knew that the nature of this “conflict” was political. Former friends, neighbors, and acquaintances do not spontaneously become enemies. As the streets became dangerous and a common public space was lost, the question for Galimov became what they had in common.

Throughout the USSR, everyone had to publicly speak the same language: Russian, the language of the empire. This language and its vocabulary were imposed on ethnic groups and violently instilled over the course of decades. This so-called “shared language” replaced the mother tongues of many communities. For Galimov, the language he used to communicate was foreign, an imperial tongue. But he hardly knew Crimean Tatar traditions. After deportation, the only way his mother could keep any relation to her native Crimea alive was to paste newspaper clippings and postcards from friends and write memories in a secret notebook. Galimov grew up with the idea that someday, his people would return home. But there was no way of knowing what was happening in Crimea, or what it was really like. No one read about the history or identity of Crimean Tatars at school or in university. Knowledge had to be transmitted personally from one generation to another, through objects, traditions, songs, decorative art, memory, and oral stories.

The memory of the Crimean Tatar deportation has been transmitted primarily through folk decorative practices, including sewing, embroidery, and painting, which depict devastated landscapes, empty roads, and nature. However, even much of this knowledge was censored. One example of this is embodied by Ukrainian ethnographer Yevgenia Spaska, who devoted her academic life to researching Crimean Tatar traditions. She originally went to Crimea as a Red Cross volunteer nurse during the First World War, where she conducted medical procedures at home. One of her patients was another ethnographer, Oleksandra Petrova, who had always admired and collected unique drawings and sketches of Crimean Tatars sewing traditions. Petrova died in 1921 and bequeathed Spaska her archive of about 1,000 drawings and 600 drafts. While part of the archive was lost in storage with some of Petrova’s relatives, Spaska used this material to write her first essay on “Old Crimean Patterns.” At the end of the 1920s, Soviet cultural policy changed (the so-called “Great Break” period). As part of a large-scale curtailment of Ukrainian studies and later repressions against those primarily researching Ukrainian and Crimean Tatarian topics, Spaska was forced to abandon this topic of research. In the early 1930s, Spaska was arrested and exiled to Uzbekistan for three years, and she never returned home. Spaska died in the Uzbek SSR in 1980, and was officially rehabilitated in 1989. The very same 1989.

When I talk about reconstruction, I mean not only the reconstruction of city space and people’s lives there—their ability to exist, to freely move and live. As a person who is interested in visual culture, I talk about the reconstruction of knowledge, transformed and salvaged visual cultural traditions, and the materiality of archives and art that are affected by violence. It is important to pay attention to new structures being formed in absences and voids. For no space is ever truly empty; only settler colonialism creates an emptiness which it fills with its own culture, knowledge, and people.

Crimean Tatars’ valuables, houses, and land were taken and settled by others. There is no emptiness there, and especially not in the hearts of those who were forced to go. What did Crimean Tatars think about in 1945 when they were given fifteen minutes to gather their belongings and leave their homes? While waiting outside, Russian soldiers peered into the windows to ensure everything valuable was left in place. Before saying goodbye to their property and land, Crimean Tatars hid documents and buried their libraries in their yards. They believed that justice would be restored one day, that they would return home and recover their hidden valuables. The farther away Crimean Tatars got from home, the greater their faith in their roots and the desire to return became. The architecture of cities, the texture of home walls, and the smell of native streets remained in memory.

A strong bond emerged over time among Crimean Tatars in exile. They built temporary housing with the belief that they would return, and envisioned their futures through daily practice. Galimov noted how traditional collective dance was transformed to collect money for everyday needs as well as acts of national cultural resistance, like printing books and preserving information about traditions. Thus, the idea of returning home was transformed into a material strategy for future reconstruction.

The tent town is on the site of self-turning in Red Paradise near Alushta, 1992. Source: Crimeantatars Club.

It was the summer of 1989.

One night, a young black-haired Crimean Tatar visual artist named Mamut Churlu heard Crimean Tatarian wedding music playing outside his window. This agitated him; he described it as if his heart was seizing. It was then that he realized it was time to go back to Crimea. He packed his belongings and bought a ticket to Bakhchysarai. He said his final goodbye to Uzbek SSR on June 5, 1989, two days before the Fergana pogroms started.

The question of returning home for Crimean Tatars was not only about restoring something lost, but first and foremost about obtaining historical justice. New families (mostly Russians) lived in Crimean Tatars’ previous homes, and their rights to that land were protected by the local governments. Furthermore, even if they could afford land in Crimea—which had recently and dramatically gone up in price—it was almost impossible for them to legally buy it (just like getting a prestigious job). However, Crimean Tatars did not give up. People like Galimov exchanged positions of authority in Uzbek research centers to become locksmiths or cobblers in Crimea. Returning to Crimea, Crimean Tatars were forced to start life over again.

In the same summer of 1989, Soviet authorities tried to colonize Crimea again by distributing empty plots of land for summer cottages to people from other regions, particularly Russians. In response to this, and still being unable to return to their former homes or obtain compensation for them, Crimean Tatars “illegally” occupied empty plots of land. The land was not particularly fertile, but they built homes for themselves on it from simple materials. Some were marked around the perimeter with an improvised fence, sometimes made of barbed wire. The state officially called these acts “seizures,” but they were in fact the return of justice. It is impossible to capture one’s own territory; it is only possible to defend it.

Crimean Tatars have tried returning home since 1945, but it was only in the late 1980s that it become more widespread. In July 1987, there were 20,000 Crimean Tatars living in Crimea, but in July 1990, there were more than 80,000, and by September of that year, there were more than 100,000. This return created social demands and exacerbated existing problems such as the lack of rights to build houses. People were forced to live in the streets, in public space. One photograph from the time depicts a temporary residence, a poster hanging from tent with “Homeland or Death” written on it located inside a fenced area.

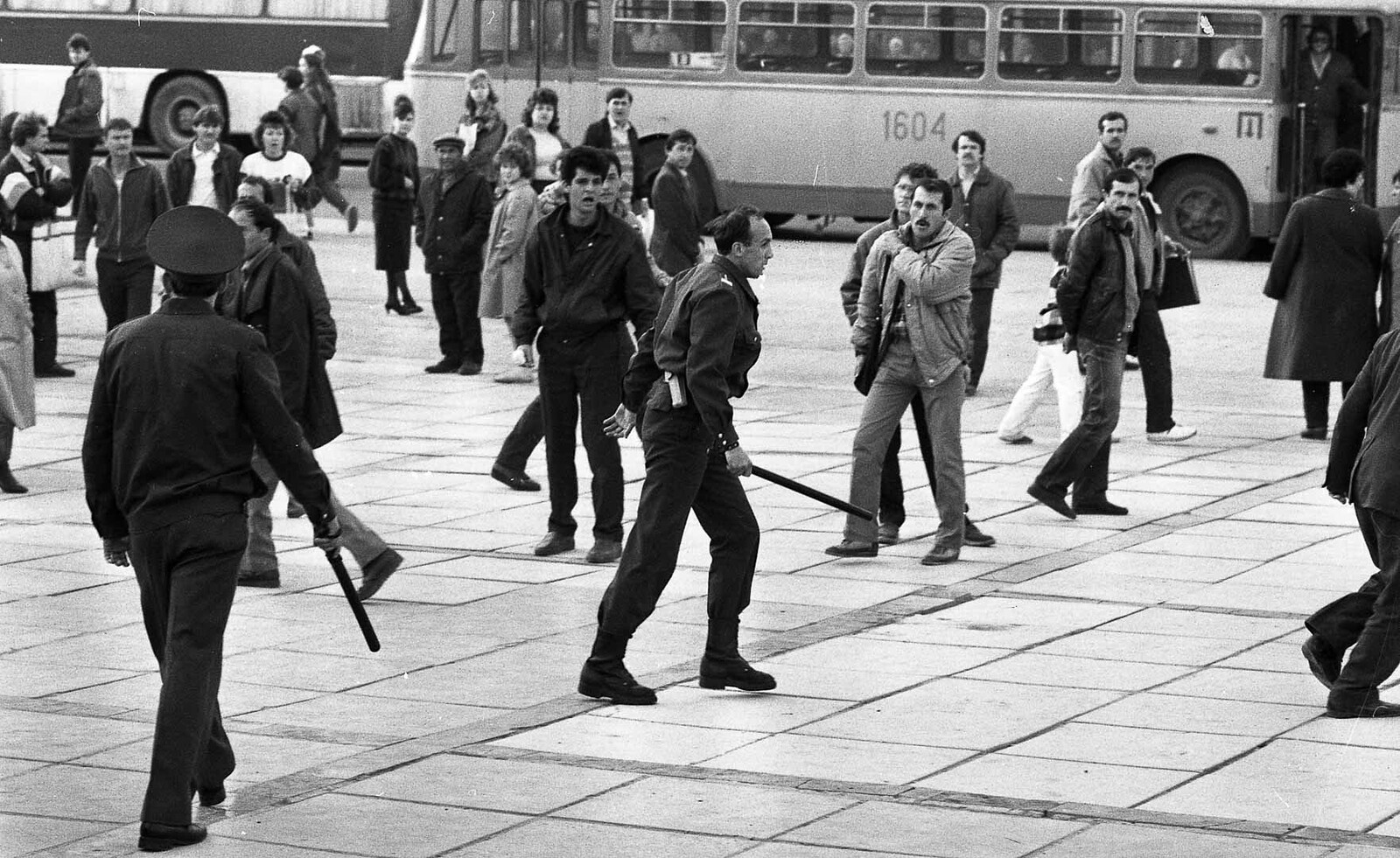

On November 27, 1989, more than one thousand Crimean Tatars took to the streets and were dispersed by the police. Two days later, local authorities wrote to Leonid Kravchuk, Chairman of the Ukrainian SSR parliament, highlighting the police’s violation of demonstrators’ rights, who were pushed with rubber batons. A year later, Ukrainian photographer Valery Miloserdov captured the Crimean Tatars’ hunger strike in Simferopol. One photograph shows a policeman brutally grabbing a Crimean Tatar girl by the collar of her light coat with no other civilians around, only other male police officers. I don’t know if this photo would have the same effect if it had been of a boy instead of a girl, but you can see her courage standing up to embittered special service employees. Recalling the episode, Miloserdov characterized the riot policemen as savages who beat everyone, even women, children, the weak, and the hungry.

Miloserdov met local Crimean Tatars who lived in haphazardly built houses and asked to show him their homes. They quickly drove away together, as if someone was trying to catch them. Miloserdov recalls this as one of the first times he felt fear. But when he arrived, he realized that Crimean Tatars were unafraid. For him, the lands on which Crimean Tatars built their houses looked impressive: unassembled boxes in the middle of the steppe, with barbed wires surrounded them. People were ready to defend themselves. Molotov cocktails were in every house. Having found their own, people were not afraid of fighting to keep it.

Back then, those protests made a difference. Building permits starting being issued to Crimean Tatars in Crimea in 1990. Among the first to receive one was the artist Mamut Churlu. He took several jobs to make enough money for (re)construction: he was a decorator at the Kerch shipbuilding plant, he made stained glass windows, and he sold his paintings. But even that was not enough. He eventually took out a loan to buy construction materials, which were quickly becoming more expensive. And it was not easy to bring them home—there was no public transportation to new settlement areas. But the dream of having a home is powerful.

By the time a roof covered his house, the artist’s once-black hair had become gray. This image of a head whose hair turns gray quickly came to symbolize the difficulty of the times and the challenges he faced. Churlu recalls: “It was difficult for all of us, but our people worked like crazy. I remember when a carpenter came to me (he was Ukrainian) and said that he admired Crimean Tatars, because we built entire cities in one year.” With the return of Crimean Tatars, Crimea’s and Ukraine’s cities also changed. Crimean Tatar culture eventually returned in the form of religious and cultural centers. Churlu was also a key figure in reviving artistic traditions in Crimea and promoted the idea of including Örne—a special system of symbols used in traditional embroidery, weaving, pottery, engraving, jewelry, wood carving, glass, and wall painting—in UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2021.

According to Vyacheslav Chornovil, founder of the People’s Movement of Ukraine, the revival of Ukrainian nationalism in the late 1980s would have been impossible without the support of the Crimean Tatars’ campaigns. Chornovil saw the struggle for independence—both Ukrainian and Crimean—as a common task. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Crimean Tatars actively rebuilt their culture in Crimea and Ukraine. The reconstruction of Crimea in the early 1990s is an example of how communities can obtain justice by restoring their own space, by undertaking constant painstaking work, and by appealing to the imagination. They were able to turn dreams into reality and rebuild their institutions after more than fifty years of absence, displacement, and destruction. The Crimean Tatar movement was a result of the long-term struggle against Russian Empire. It was rooted in the idea of restoration, which includes language, culture, society, as well as dress and the historical and ideological fabric of towns and cities.

It is now the summer of 2023.

After more than a year of a full-scale invasion, I am writing from a temporary apartment. On the opposite side of the street, there are street clocks, perhaps from the early 1980s, that show a different time than my laptop. I do not know if they’re in a hurry or running late. Maybe they are the only ones who tell the truth. Today, living in Kyiv, I think about how violence has transformed my sense of time and home. The house has ceased to have physical walls. Instead, the whole country has become a giant home without walls. The missile defense system, as a roof, protects me.

The contemporary Ukrainian social body was influenced by thoughts about and protests for freedom. It survived the Chornobyl disaster and was formed on the streets, sitting on the granite of the Maidans, feeling the space and limitations of the roads. This body endured the pain of rubber truncheons and bullets; it lived in self-built houses, and it remembers the darkness of the 1990s. Indeed, our society is changing due to various economic, political, and social issues, but most importantly, security. Reconstruction will not start spontaneously after the war; it is already taking place. The frontline cities will be rebuilt after the front leaves, but the formation of memory, history, and culture is already taking place. Ukrainian social memory is a powerful foundation to resist Russian aggression. It allows for new artworks to be created and institutions to be restored which are based on the principles of freedom and respect for human rights. The reconstruction of Crimean Tatar culture and society in the late 1980s, for instance, did not end once Ukraine got independence; it continues into the present.3 While none of our houses today have a poster hanging reading “Homeland or Death,” we have no fear. This spirit and the belief that we will one day cross the threshold back into our own houses is unshakable.

There is no fear of the future, as I know that it exists.

Meskhetian Turks are a subgroup of ethnic Turkish people formerly inhabiting the Meskheti region of Georgia, along the border with Turkey, who were forcibly deported by Stalin to Central Asia in 1944.

Local historians note that Crimean Tatars have been trying to return since the 1950s and have counted several waves since then. Still, to a greater extent, the return occurred precisely during the late 1980s, most significantly in 1987-1989.

For example, on March 6, 2023, relised the National Commission for the Crimean Tatar Language that will work on Crimean Tatar orthography to popularise culture and launguage.

Reconstruction is a project by e-flux Architecture drawing from and elaborating on Ukrainian Hardcore: Learning from the Grassroots, the eighth annual Construction festival held in the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture on November 10–12, 2023 (2024), and “The Reconstruction of Ukraine: Ruination, Representation, Solidarity,” a symposium held on September 9–11, 2022 organized by Sofia Dyak, Marta Kuzma, and Michał Murawski, which brought together the Center for Urban History, Lviv; Center for Urban Studies, Kyiv; Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture; Re-Start Ukraine; University College London; Urban Forms Center, Kharkiv; Yale University; and Visual Culture Research Center, Kyiv (2023).