Oppressed peoples are always asked to stretch a little more, to bridge the gap between blindness and humanity.

—Audre Lorde1

On May 28, 2020 at around 10pm, I received a notification on my phone. It was a Slack message from my boss, the director of a fulfilment center of an online supermarket located in the port of Rotterdam. The message said that the first case of Covid-19 had been identified inside the warehouse, and that starting tomorrow all workers should wear face masks on the floor for one week. Unlike public transport and grocery stores, this was the first time face masks were made mandatory in the fulfilment center, a full two months after lockdown in the Netherlands had started. When coronavirus was declared a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, the director had sent another Slack message, announcing that the “food supply chain in the country had been identified as essential for the continuation of Dutch society.” The fulfilment center would remain open and we, the “essential” workers, would continue to come to work. I was essential for the continuation of society, yet clearly, in my forced exposure to the virus, expendable.

We all knew we had been working at risk since the pandemic started. But still, that second Slack message announced in a very blunt way what we already knew: the fulfillment center was a contact zone, and that all of us warehouse workers were more or less fucked. The national lockdown and state policies of “social distancing” only allowed the mostly white middle class to stay at home. In the meantime, and together with 400 other warehouse workers, I was “picking” the toilet paper and canned food these middle-class customers were ordering online.

Something else also happened the same week that face masks became mandatory inside the fulfillment center. A few days earlier, on May 25, George Floyd was murdered by a white policeman in Minneapolis. Maybe it was because of the rage provoked by the injustice of his death that had been all over the news that week, maybe it was because he was also an essential worker, or maybe it was because most of us warehouse workers were brown and black bodies, but after I received that message by my boss, a white Dutch man, a feeling of anger and frustration I hadn’t felt since the pandemic started to flood my body. For the first time, I was terrified to go to work.

Clearly, these emotions were covering a deep and intense feeling of fear. But this fear was different from what was brought on the pandemic, which made those who could afford it to empty supermarket shelves and stay in the safety of a home. The kind of fear I felt was bound to the color of my skin, to my condition as a brown immigrant in the Netherlands. It is a fear that has been exacerbated during the crisis, and will remain long after the pandemic is gone. This second Slack message in the pandemic reassured my destiny of unescapable precarity and exploitation.

Like every other Saturday that I went in to work, I woke up late. This meant I didn’t have time for breakfast. With the added anxiety brought on by my empty stomach and the racial inequalities and unfairness of advanced capitalism, I left my house and cycled my way towards Rotterdam Central. The station, which was usually crowded and noisy, was now mute and empty, available only to us, the essential workers. Once in the train car, with my head leaning on its window, I saw Rotterdam’s cosmopolitan city center progressively disappear as we moved towards the segregated south.

I thought of the past five years I had lived in the Netherlands. I thought of how scholarships for non-EU students allow for a European dream, but don’t pay rent. I thought of all the restrictions imposed by my visa which make it impossible find another job, and impossible to continue accepting barely-paid cultural internships. Without the income of my job at the port, I would have to leave graduate school and go back home, to Mexico. There, as in the rest of the so-called “global south,” the pandemic had kicked in with much more force and unfairness, and poverty and precarity has always been more violent.

By the time the metro reached Zuidplein and Slinge, the two largest metro stations in the south, it was mostly only people of color who got in. As I recognize some of the workers getting in, I remembered an old roommate, a white Dutch guy, who once told me that Rotterdam is considered the “least Dutch city.” He probably meant the least “white” Dutch city. Almost half of Rotterdam’s population has an immigrant background. A large part of the city’s population of color, as well as workers in the fulfillment center, come from Suriname and Curaçao, where the Dutch empire traded slaves until the late nineteenth century.2 The south is also were most of my artists friends live, white and non-white. Their tiny houses are increasingly becoming targets of gentrification, and the precarity of their rent contracts allow their landlords to easily evict them.

The fucking castle. Image: Denisse Vega de Santiago, 2021.

After twenty minutes, we got off the metro in Rhoon, a wealthy neighborhood in the countryside. With all the urban contradictions of the south, even further south, closer to the port live wealthy white Dutch families. Beautiful Dutch cottages with open windows surround the narrow streets that I cycled through together with other essential workers. Their sailing boats, Mercedes, and immaculate gardens were visible while crossing the street. Before lockdown, the wealthy residents of Rhoon used to enjoy rare sunny days in the open-air cafe of the Castle van Rhoon, which has now been turned into a luxurious hotel. The castle’s main entrance was guarded by two statues of dogs, one on each side. I’ve never seen a black or brown family anywhere near this castle, or anywhere else in the neighborhood.

As I continued my way to the factory, two smiley little blond girls riding their ponies in the opposite direction waved at me. Their moms, who were riding normal sized horses, limited their greetings to a timid smile. That particular day—crossing that immaculate Dutch countryside, its stupid castle, and the white Dutch women barely smiling at me—felt more obscene that usual. Capitalism itself was parading on its presumptuous horse, dictating who had the right to stay in safety and who had to go to work to a contaminated building—namely, descendants of slaves and brown immigrants.

After the passive aggressive parade of structural racism, a long wall made of thousands of little stones, one-kilometer-long and no more than five-meters-tall, marks the end of the road. The wall had been put here to prevent noise from the industrial boulevard from disrupting the wealthy neighborhood. An opening in its middle divides the wall into two, connected only by a small wooden door. This wooden threshold at the end of the road is crossed by every single essential worker on their way to and from the fulfilment center. Written with black marker on the metal frame of the wooden door reads “Dutch girls love Black dick!” followed by an illustrative drawing. Clearly this was not a message about love, but about objectification, the exoticization of the other, and the containment of desire in racial stereotypes that is so embedded in “innocent” whiteness.3

The wall establishes the end of a world of countryside idyllic privilege, and the beginning of a port of highly-industrialized exploitation. Warehouses and ship containers of various colors piled one on top of the other replaced the wealthy cottages. Far away, I could see the towers of Shell’s oil refinery deeper into the port, the largest in Europe. Next to these shiny towers, I could also see tall, powerful, imperturbable container cranes slowly moving. The colossal and immense machinic beauty of Europe largest port was always in movement, always silent. This silence promoted the idea that the port is empty and the illusion that everyone during the pandemic was in safety, at home. But the port had not been emptied. We, the thousands of port workers, were very present at its very heart. It was our labor that allowed for its very existence.

As I went through the gates of the fulfilment center I crossed through the parking area, zigzagging in between some trucks awaiting their turn to unload in one of the eleven monumental truck entrances. One of the drivers, Berwan, a short and rather chubby man standing outside his truck smoking, shouts “Jalapeño!” and waves at me while I pass. He always calls me that, and I like it. Berwan came first to the Netherlands as an asylum seeker from Kurdistan. The look in his eyes is one of the kindest I’ve seen.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the workers’ entrance was no longer visible. A white tent had been placed in front, whose two conic elevations at its center made it resemble a circus tent. The circus of capitalism. Once inside the tent I got in line behind another worker. Soon more workers get behind me. As the line moves I eventually enter the building and find another warehouse worker dressed as a doctor waiting for me, sitting behind a window in a small dark room. Holding a thermometer in her hand, she places it close to my forehead as soon as I step in front of the window opening. She looks at my temperature, registers it in her laptop, and gives me a plastic band. “Enjoy your shift!” she said.

The next room was the “changing room,” crowded with lockers and benches attached to its bright red prefab walls, where the workers can change who still haven’t donned their uniforms. The average warehouse worker wears a red t-shirt and matching sweater, or orange in case they were a “trainee.” Other colors and more comfortable shoes were available for people in more advanced positions. Since I was already in uniform, I went directly to the other side of the room to get in another line to pass through two electric rotating doors in the middle of a huge five-meter-tall steel fence. Once my turn to enter arrived, a sound indicated that the door had been activated. After placing my log-tag on a magnetic plaque next to it, I pass through.

The fulfilment center is a hermetic shoebox whose interior spaces is equally isolated and window-less. Everything about this ten-meter-tall building was designed for the transport of products arriving from trucks. Inside, everything moves. Everything has wheels. It is a architecture of processing that is turned on at all times. The first workers get in at 3am and the last ones leave at nearly 1am. Each of the 400 workers walk an average of twenty kilometers per nine-hour-shift.

I walk towards the nearest time clock, clock in, and take one of the available scanners from the table next to it. As I place the scanner on my arm and log in, I approach one of the nearby screens and look for my name. Unsurprisingly, I find it under the section of “chilled” and in the subsection of “picking.” Only the fastest pickers are sent to chilled. Clearly, I was very fast. Wearing the red uniform, a face mask, industrial shoes, a thermal jacket, working gloves, and with the scanner attached to my arm, I walk towards the back of the building with the freezers. My shift hasn’t even started, but my data has already been collected at least four times.

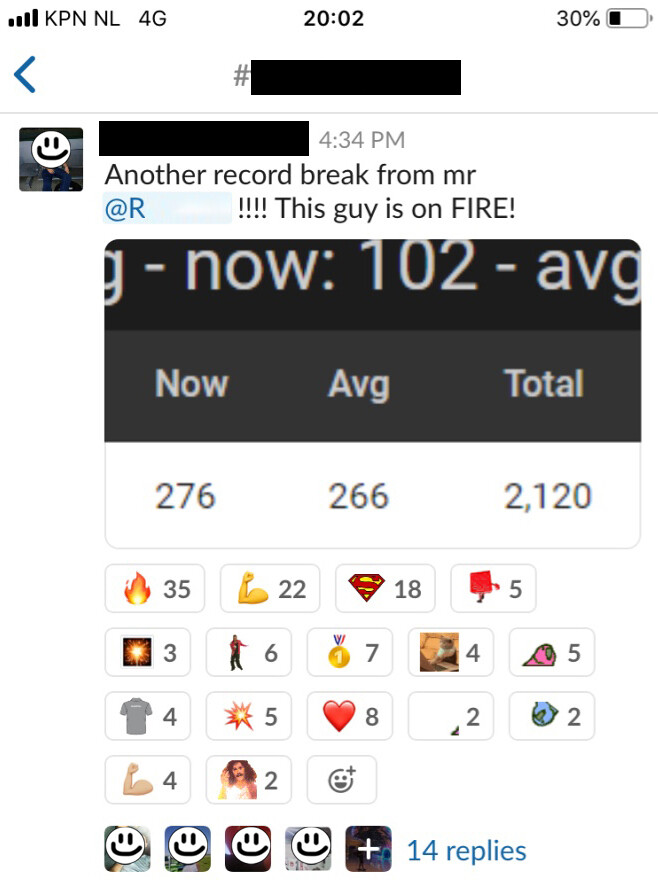

Walking to the chilled area, I am seen by several surveillance cameras attached to the roof. Inside the fulfillment center, everything is surveilled and controlled, both products and workers. The prime example of workers’ surveillance inside the warehouse are the score screens, which are positioned at the entrance of the fridges. The screens list the speed of every picker while picking, from the fastest to the slowest. They also function as trackers, indicating our exact position inside the aisles. As soon as we finish a round of picking, pickers gather around the screens, hoping to find our name first in the list. The score screens define our working day, the exhaustion of our bodies, our self-exploitation, and our future in the company. Supervisors, or “captains,” also gather around the screens, and can access them online. Essential job, sophisticated surveillance.

There is a kind of adrenaline to the freezers. As soon as you enter, a foggy, creamy, fresh atmosphere drags you in, makes you part of the space like a nightclub or a gym. The music is quite loud, and everyone moves fast because it is so cold. All the products are arranged on shelves, which in turn are divided in various aisles, like in a supermarket. Because of the cold, products can be closer to each other, which makes it easier for pickers to pick them faster. I grab one of the electric picking cars parked in the beginning of the first aisle, select “picking” on the scanner, and scan its number. “3x A-17-01-1 to 14.”

Each picking car contains twenty-one numbered totes, and one picking round can take up to forty or fifty minutes, depending how fast the picker is. Before reaching the speed scores that allowed me to pick at the freezers, I used to pick in the ambient areas, where trainers constantly gave me feedback on how to move faster, and how to make less mistakes while scanning. At the beginning of the picking round there is always traffic, with pickers getting stuck picking two-liter bottles of milk, one of the most in-demand products and also one of the heaviest. But as we continue to move, products become lighter, and we start to move faster.

It wasn’t difficult to work faster, even during the crisis. After the pandemic hit, the profits of the company skyrocketed. The number of aisles increased, the picking cars became heavier. So did my industrial shoes, and the tiredness of my body. Yet we, the pickers, seemed to also become faster, despite our anxieties and fears. The discomfort of wearing a face mask while picking made us more anxious, which in turn only made us go faster. Stretching our arms between the aisles, reaching, grabbing, scanning jars of pickles, of yoghurt, the scanner, meat, vegetables, the picking car, the pink creamy hummus…

Affect: passionate self-exploitation of colored workers and its capitalist intrumentalization. Image: Denisse Vega de Santiago, 2021.

Whenever a speed record was broken, it was shown on the score screens and the supervisors congratulated the picker publicly via Slack. Everybody saw the post. Everybody commented. Everybody added emoticons. Affect. Another trick of the port’s circus of advanced capitalism: instrumentalizing the adrenaline and passions of the mostly black and brown warehouse workers; normalizing our anxieties, our fears, our precarity.

Midnight finally came and it was time to go home. I finish work just in time to catch the last metro, which leaves at 00:19. By the time I leave the warehouse I am so tired I can barely feel my body. My migraines and the pain in my knees have only increased since the pandemic started. I got rid of all my equipment, logged out, clocked out, passed through those metal doors again, picked up my bike, and left.

As I cycled back to the threshold of the port, I realized how this silly little wooden door seemed much more charming during the day, approaching and crossing through it from the wealthy neighborhood. From this side, and at this time of night, it actually looked quite scary. The complete darkness and silence, the separation of the two walls and the little corridor between them made me feel like I was in as isolated space of a space as the one I just spent the last nine hours in. Whoever designed it didn’t think about the people on the other side of the wall.

As I open the wooden door and walk two steps onto the other side of the threshold, I see in front of me six immense shadows, darker and heavier than the rest of the landscape. I take two more steps before I sense breathing next to me, and recognize a group of six massive horned hairy cows stood just a few centimeters away. I had heard about these cows from other workers, but had never seen them myself. They were apparently brought from Scotland to keep the grass short, and while they were inoffensive, everybody was still afraid of encountering them, especially at this time of night. I too was petrified. For few seconds I couldn’t move, more terrified than when I received that Slack message the day before.

There I was in this threshold, between one word and the other, in front of another danger the port subjected my body to. Yet I could also recognize myself in these hairy figures breathing in front of me. Just as I was a brown immigrant brought to the port to move hummus and milk, the cows had also been brought here for a different kind of labor. I gathered together my anxieties and exhaustion, my remaining adrenaline, my fear, and my frustration, held tight to my bike, and walked pass the horned hairy cows.

As I passed them, hearing and feeling their breath next to me, I imagined becoming one of them; something other than myself in that moment, in these circumstances, in this destiny of perpetual danger and violence. Finally embodying the violence and exploitation that frightened and exploited my body for so long, I felt myself mutate into a half-machine, half-hairy cow, half-brown working-class Mexican immigrant. Now as this mutant other, I passed by the castle again, briefly stopping to dance in front of the dog statues and then continue my journey. I passed by the wealthy cottages and finally stopped under a big three. I was so tired, my knees still hurting. I sat in the grass, under the big tree, moved my horns around, and fell asleep.

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider (Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press, 1984).

The Dutch eventually found the slave trade to be not very not profitable, partly due to the high mortality rate of slaves when crossing the ocean; 30% of the slaves died on the ships.

Gloria Wekker, White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016).

Workplace is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Canadian Centre for Architecture within the context of its year-long research project Catching Up With Life.

Category

Subject

Thanks to Natasha Marie Llorens for her long term guidance on finding the adequate words and feelings for this story.