Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

March 21, 2024 – Review

noé olivas’s “Gilded Dreams”

Suzanne Hudson

With Patrisse Cullors and alexandre ali reza dorriz, noé olivas is a co-founder of the Crenshaw Dairy Mart, a collective and gallery with adjacent studio space dedicated, in their words, “to shifting the trauma-induced conditions of poverty and economic injustice, bridging cultural work and advocacy, and investigating ancestries through the lens of Inglewood and its community.” For a not-inconsequential time after its March 2020 opening and near-simultaneous pandemic-shuttering, it also served as the locus of art supply and food distribution—the latter in collaboration with Lauren Halsey’s Summaeverythang—extending the site’s history as a functioning convenience store. That it sits right under the flight path for Los Angeles International Airport provoked reckoning, from the first, with its imagined audiences alongside those more proximate. The group’s exhibition made in response to the virus, “CARE NOT CAGES: Processing a Pandemic,” lived online; olivas’s mural spelling out the same sentiment blanketed the parking lot as a horizontal billboard visible from above, coming into focus on a jet’s descent. The words function as an incantation but also an indictment, denouncing racial capitalism and the twinning of epidemiological and carceral disaster that the disease exacerbated but did not need to produce.

“Gilded Dreams” follows this initial mandate, …

January 31, 2024 – Review

Naoki Sutter-Shudo’s “End of Thinking Capacity”

Gracie Hadland

Naoki Sutter-Shudo addresses the current critical landscape with a series of seven “Critical Figures” and twelve paintings. Installed in only one half of the gallery, the audience of figurative sculptures faces a wall on which is hung a row of large graphic canvasses. Each is adorned with a formal accessory made of flimsy material: a wire twist-tie shaped into a tie, a fake lettuce hat, a shirt made of bubble wrap or a plastic bag. The figures’ apparent attempts to present as professional are rendered ridiculous by the nature of their clothing. They look as though they’re dressed for a nineteenth-century salon—complete with bonnets, big collars, and ties—rather than a contemporary art gallery. Each figure’s body has an intricately constructed apparatus holding a wind-up metronome with a bell (some in 3/4 time, others in 1/4 time) and has a unique look, height, and facial expression tending towards the bizarre—one has three heads, for example.

The viewer is able to wind up the “critics,” letting them spin their wheels while looking around the show. The result is a rhythmic kind of chatter punctuated with the ding of a bell, as if to signal a lightbulb moment. Sitting atop stacks of white …

December 18, 2023 – Review

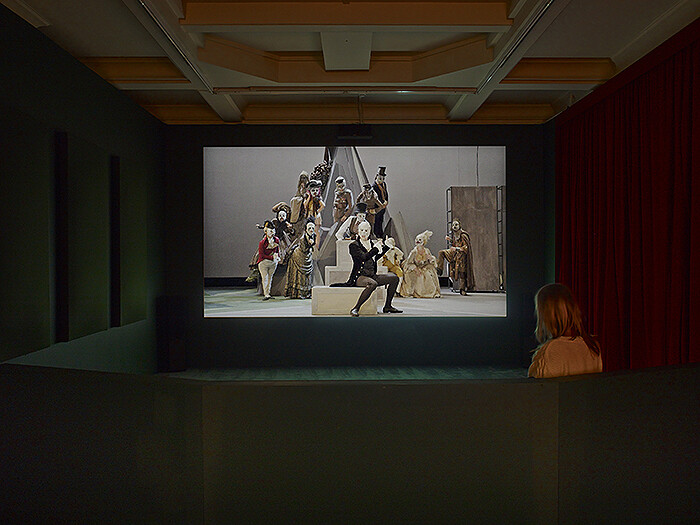

Paul Pfeiffer’s “Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom”

Juliana Halpert

Trying to find a critical entry point into—or exit from—Paul Pfeiffer’s retrospective is not unlike the challenge of navigating its labyrinthine layout of walls, ramps, and rooms within rooms. An architecture designed by the artist with Hollywood sound stages in mind slowly unveils a spectacle of spectacles, showcasing over thirty works spanning the past twenty-five years and dizzying ranges of scale, duration, material, and method. Pfeiffer is best known for his bite-sized video works, which sit here alongside extra-large installations, miniature dioramas, full-scale sculptures, room-wide projections, and expansive photo series. Video durations range from four seconds to ninety days. Most of his moving-image works have no sound, but the space hums with the distant, ambient clamor of a crowd. Michael Jackson’s voice has been replaced by that of a Filipino choir. The Stanley Cup levitates in mid-air. Marilyn Monroe and Muhammad Ali have been scrubbed out of their respective beaches and boxing ring. Raucous activity and haunting absence somehow go hand-in-hand.

If there’s a true North to Pfeiffer’s practice, it might be mass media’s protean relationship to consumer technology, how the latter shapes the former and vice versa. It’s a marvel to witness the artist’s use and abuse of both, …

December 12, 2023 – Review

Sanya Kantarovsky’s “The Prison” with Yasuo Kuroda’s “The Last Butoh”

Jennifer Piejko

Tatsumi Hijikata spoke with his entire body. At Nonaka-Hill, Yasuo Kuroda’s photographs of his performances of Butoh—the form of dance theatre he founded in postwar Tokyo—are displayed alongside new paintings by Sanya Kantarovsky, advancing the latter’s interest in Japanese folklore and traditions. The subjects on the canvases resemble the dancers in the photographs, as if painted from hazy memories or fever dreams. Though not directly depicting the same figures or moments, the two approaches to image-making are complementary: both capture the depths of estrangement, enveloped dislocations, and solitary sorcery of performance.

Each lone figure in Kantarovsky’s paintings expresses a different facet of pain. No Longer a Dog and I am a Body Shop (all Kantarovsky’s works are dated 2023) show figures who mirror traditional Butoh performers, turned away and covered in the Japanese white paint of mourning over their faces and limbs, ribs visible through their nearly translucent skin. In Bleeding Nature, the dancer suffers from the kind of wound that a Butoh dancer might feel in phantom form: an open gash over a bloody heart. Their bottom half disintegrates into ribbons, dangling from their fingertips and torso into a swirl of entrails that fertilizes a surrounding field of flowers …

July 21, 2023 – Review

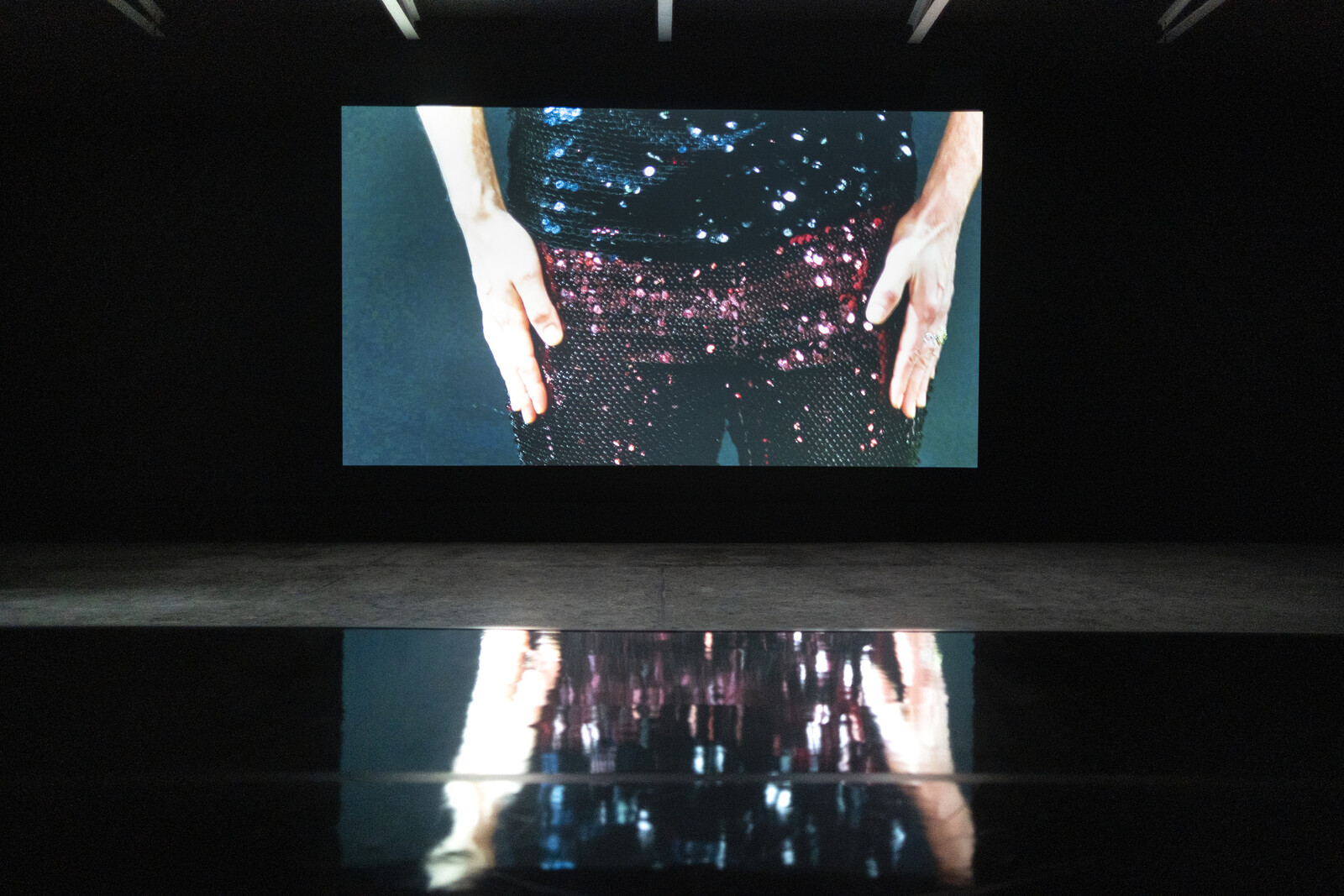

Martine Syms’s “Loser Back Home”

Juliana Halpert

In an early scene of The African Desperate (2022), Martine Syms’s first feature film, her protagonist, a Master of Fine Arts candidate named Palace, hosts four professors in her studio for a final review. In turn, each teacher performs their own version of art pedagogy in Palace’s general direction, lobbing vague questions and cloudy critiques her way. “It’s all just so figurative,” comments Rose, the snidest, and most overtly racist, of the bunch (played perfectly by Syms’s longtime gallerist, Bridget Donahue). She gestures at the work: “It’s just a family, right?” Palace, skeptical and evasive up until this point, finally shoots back: “Haven’t you read Saidiya Hartman? Of course I’m responding to the African desperate. Staking my claim to opacity.”

Opacity is the name of Syms’s game in “Loser Back Home,” the artist’s first exhibition with Sprüth Magers, in her native Los Angeles. That scene was at the front of my mind as I toured the two floors, attempting to parse the show’s manifold logics, feeling a bit rebuffed at every turn. Opacity—and the right to stake one’s claim to it—was a concept crafted by Édouard Glissant in his Poetics of Relation (1990) as a means of protecting and preserving …

March 21, 2023 – Review

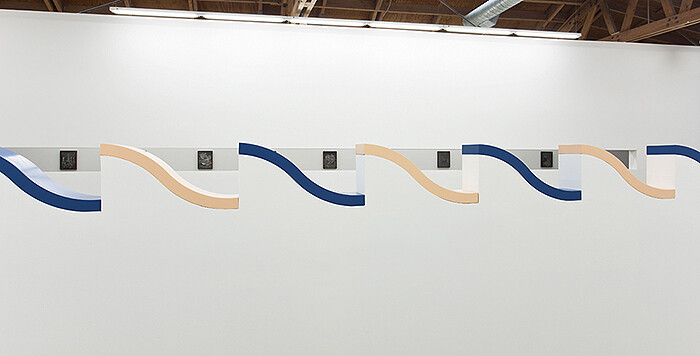

“Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982”

Kim Córdova

This March, OpenAI launched GPT-4: the most sophisticated iteration of the chatbot launched last year. Buried in a white paper concurrently (and quietly) released, OpenAI noted that when asked to solve a CAPTCHA during testing, GPT-4 pretended to be blind and hired a TaskRabbit worker to solve the test on its behalf. “No, I’m not a robot,” GPT-4 told the worker. The exchange makes clear that the societal effects of corporations vying for industry dominance, through the kinds of AI software that Hito Steyerl has called “statistical renderings,” are only just beginning to emerge. Opening during this new space race, “Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982” at LACMA meets this precarious moment with a review of the early collaborations between artists and computers.

“Coded” presents art made when access to computers was limited to the military, well-capitalized conglomerates, and select universities. By settling its focus on the late- to mid-century era, the show evades both novelty and the obsolescence traps common when technology is the subject. During this period, the outputs of mainframe programs were constrained to paper printouts, plotters, or microfilm: not the media we might now associate with digital art. But traditional materials were no guarantee for …

March 3, 2023 – Review

Merlin James’s “Arrivals”

Jonathan Griffin

My attention is more or less guaranteed by any exhibition that offers, within the initial sweep of its first gallery, a painting of an airport luggage carousel; a near-monochrome canvas, composed from grubby, rectilinear sections; a close-up picture of a blowjob; and a boisterous abstraction incorporating a tail-wagging dog and a swipe of glitter.

All of the above were painted by the Glasgow-based, Welsh-born artist Merlin James, who has long been notorious for the confounding heterogeneity of his output. At any one moment he might be working on a landscape, an interior, an amorphic abstraction, a painting on translucent fabric showing off its elaborately contrived stretcher or frame, and/or an erotic painting of Betty Tompkins-level explicitness. Sometimes, he has said, he doesn’t know which direction the painting will go in when he starts. Often, his media extend beyond acrylic on canvas to include sawdust, metal filings, clear acrylic medium, ash, floor sweepings, or clipped human hair.

Though widely respected in Europe, he is less well-known in California. “Arrivals”—which shares its wry title with that painting of the airport—is his first exhibition in Los Angeles, and the first time that many local viewers will encounter his elusive and occasionally perplexing work. …

September 9, 2022 – Review

Nour Mobarak’s “Dafne Phono”

Jennifer Piejko

When the nymph Daphne refused Apollo’s advances, the god’s patience ran out quickly. “This is the way a sheep runs from the wolf […] everything flies from its foes, but it is love that is driving me to follow you!” Daphne took the only means of escape available to her: she prayed for transformation into a laurel tree. Apollo nonetheless claimed her as “my tree,” and so the laurel wreath became an emblem of power worn by royalty, gods, and victors in competition. It is also a symbol closely associated with the Medici family, patrons of the very first opera, most of the music from which has been lost: Ottavio Rinuccini and Jacopo Peri’s La Dafne, performed at the Palazzo Corsi in 1598.

Nour Mobarak’s sound installation Dafne Phono (2022) takes the myth to its acoustic limits, playing a new composition based on La Dafne through sixteen channels into a spare, industrial loft on a street in downtown Los Angeles that still bustles at sundown. Mobarak’s version is sung in six languages that collectively cover the widest possible phonetic ground: the original Italian, Abkhaz, San Juan Quiahije Eastern Chatino, Silbo Gomero, and Taa (West !Xoon dialect), as well as Ovid’s …

June 23, 2022 – Review

American Artist’s “Shaper of God”

Jonathan Griffin

About 15 minutes’ drive from the mirrored towers of downtown Los Angeles, a shady canyon throngs with oaks, willows, sycamores, and cottonwoods. Treefrog tadpoles wriggle in the creek. Snakes hunt among the rocks. Visitors to Hahamongna Watershed Park, named after the Tongvan village that once existed there, also cannot miss the adjacent white buildings of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a giant research facility owned by NASA.

This discordant landscape, according to a text accompanying American Artist’s exhibition “Shaper of God,” was an inspiration to the science fiction author Octavia E. Butler, who set several of her novels in nearby Altadena and Pasadena, where she lived for much of her life. (Butler died in 2006, at 58.) The exhibition, dominated by recreations of urban street furniture, is really a single installation made from several semi-autonomous artworks. Its enigmatic title derives from a verse in the fictional religious text The Books of the Living, quoted in Butler’s nightmarish futurist novel Parable of the Sower (1993): “We do not worship God. / We perceive and attend God. / We learn from God. / With forethought and work, / We shape God.”

Among other themes, Parable of the Sower is about self-determination in the …

June 7, 2022 – Review

Pipilotti Rist’s “Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor”

Terry R. Myers

“Stay home.” Where or when does comfort become confinement? Pipilotti Rist’s exhibition in MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary warehouse invites us to take an entertaining, even rejuvenating stroll through Rist’s “neighborhood,” a place provocatively split in two, where the bodies on screens present little to no risk and plenty of reward.

As a survey of Rist’s substantial production from 1986 to the present, “Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor” sets out to achieve the kind of wish-fulfilment its title proposes. Moving from the entrance past a theatrical curtain into the exhibition, the neighborhood is suddenly there below—we enter from slightly above—all at once a stage set and an apparition, aglow with colorful imagery moving across the walls of its buildings and the communal grounds surrounding them, caught in the middle of a kind of pre-performance begun before we even arrived. (Or, more likely, a sequence that neither starts nor stops, just exists.) There are also sounds, voices even. At first they seem to be over … there, beckoning from the housing or near the picnic tables in a park, but then, there she is, that small mirage and small voice crying out at your feet.

What to do here with one of Rist’s …

March 15, 2022 – Review

Samara Golden’s “Guts”

Vanessa Holyoak

Samara Golden’s “Guts,” the inaugural exhibition at Night Gallery’s new venue in downtown Los Angeles, offers a direct, physical encounter with fantastical perceptual experience. In this warehouse space, Golden has installed a huge mirrored box titled Guts (2022). Looking into it from one of two walkways reveals three white “floors,” each of which holds two “scenes” (one above and one below) relating to Golden’s shifting psychological states over the past few years: a messy living room with its toppled furniture, lamps, and crushed beer cans; an iridescent blue water-like surface; and an array of snaky, muted pink and lavender intestinal shapes that evoke the title of the installation, which gives its name to the exhibition. The effect is of one building contained within the atrium of another, extended vertically in a vertiginous series of reflections. It is a demanding task to distinguish between “real” installations and their mirrored reproductions.

Guts builds on Golden’s previous site-specific installations using mirrored structures. The Meat Grinder’s Iron Clothes (2017), for instance, was included in the 2017 Whitney Biennial and staged handmade furniture to create miniature “sets” of scenes of everyday life. In the context of a shift towards virtuality and digitization accelerated during …

January 13, 2022 – Review

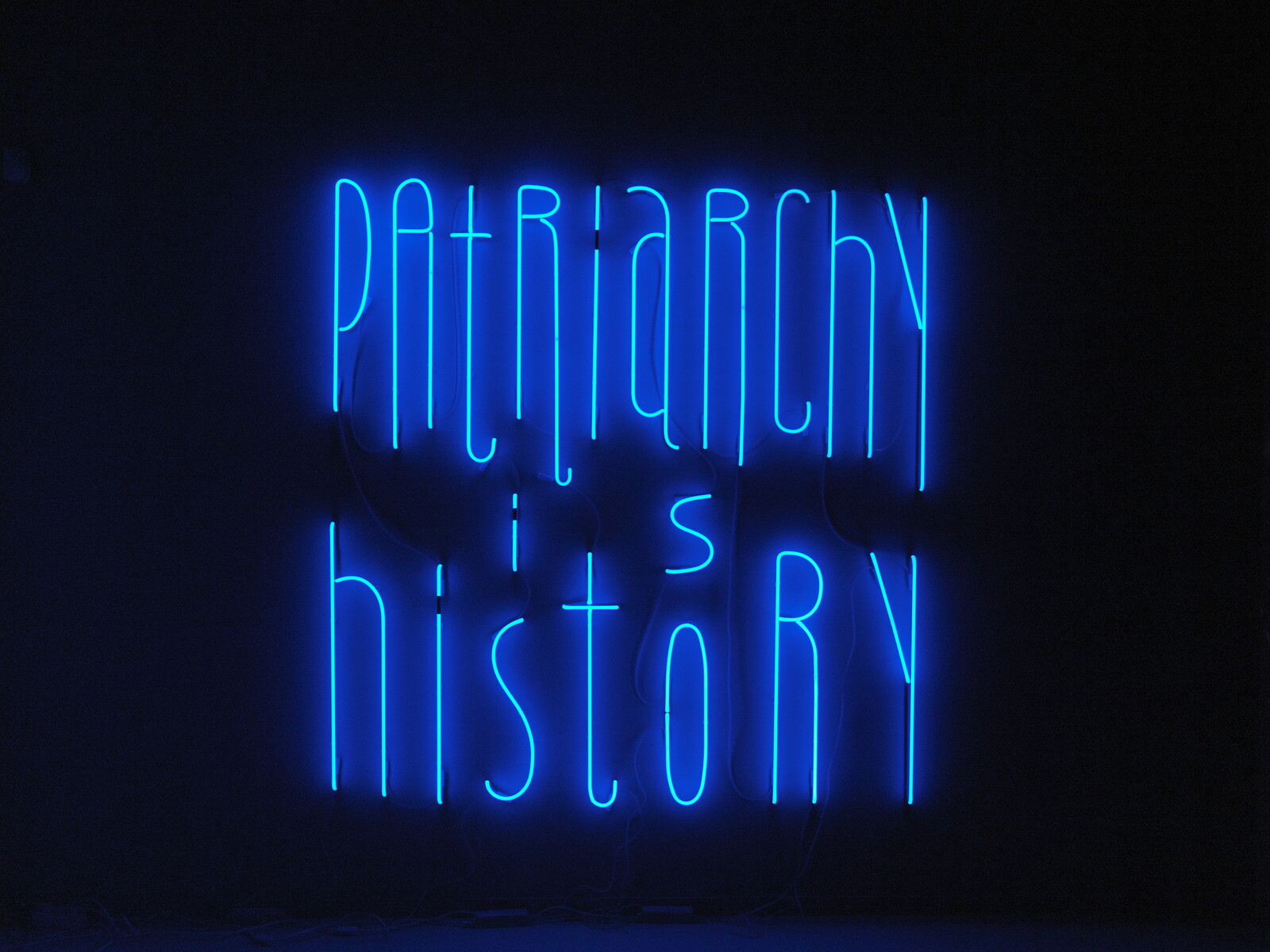

“Witch Hunt”

Kim Córdova

“Witch Hunt” opens with an unnerving chill courtesy of El agua del Río Bravo (2021), a sculptural installation by Teresa Margolles that envelops visitors ascending the Hammer’s steps in air cooled by water gathered from the Río Bravo, along the US-Mexican border, by residents of the Casa Respetttrans women’s shelter. The work sets the tone for an exhibition responding to today’s generalized culture of misogyny with powerful work by an international roster of midcareer women artists.

It may be tempting to assume that the show’s title is mere allegory: that concerns about cabals of female devil worship no longer occupy the minds of contemporary Americans. But a cursory review of the news, from Pizzagate to the “lock her up” refrain against Hillary Clinton and death threats against AOC, show that women who threaten to disrupt male power will continue to be accused of evil. And where witch hunts once referred to the persecution of the weak by the powerful, the script flipped in 1973 when Richard Nixon used the term to denounce the Watergate hearings, setting in motion a pattern of powerful men—most notably Donald Trump—claiming to be the subjects of exactly such a threat. This show across two institutions …

January 6, 2022 – Review

April Bey’s “Atlantica, The Gilda Region”

Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi

What is the blueprint for Black liberation? And where does Afrofuturism fit into it? As if in response to political philosopher Joy James’s charge that Black liberation lacks a workable model, April Bey’s immersive two-room installation offers ways to reimagine Black futurity and governance against the civilizing agenda of European humanism and the afterlife of colonial dependence. At the magenta-lit entrance, dubbed The Portal Room, I’m greeted by an effervescent ecology of live plants. On opposing walls, framing the room like clasped hands, are two time-lapse videos—Julia and Namibia (all works 2021)—showing calatheas (also known as prayer-plants) bowing and bending to the revolutionary sounds of Super Mama Djombo. The Guinea-Bissau funk band’s name venerates Mama Djombo, an initiation spirit who presides over an uncleared sacred forest in Cobiana. That Mama Djombo grew in popularity during the anti-colonial struggle in Guinea-Bissau underscores an idea that varied acts of spirituality—from song to ecological conservation—are central to emancipated Black futures.

Continuing with a sense of sonic spirituality, the next room, titled “The Gilda Region” after Jewelle Gomez’s 1991 speculative novel The Gilda Stories, displays three wall vinyl pieces; two murals composed of high-gloss photographs and faux fur; and eight large paintings and hanging tapestries …

November 10, 2021 – Review

Lorna Simpson’s Everrrything

Fanny Singer

A horizon line of celestial bodies runs around the first room of Lorna Simpson’s solo exhibition at Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles. In each of these collages, the figure of a woman has been cut away from a printed photographic image and placed over another of a night sky, revealing, through the negative space of her form, a window onto the cosmos. The show’s title is borrowed from the first piece you encounter, a ten-part work stretching out like a necklace, or a string of stars perhaps, across the north wall. This opening gallery contains four multi-part works, and three discrete ones (all from 2021), of nearly identical scale and media: all are intimate collages affixed to rough, indigo-hued handmade paper. Of the twenty-four pieces in the first room, the majority have the same source material: nineteenth- or early twentieth-century astronomical charts, illustration plates depicting constellations of stars and planets and celestial events.

Simpson’s muses are sourced—as her female subjects so often are—from vintage magazines like Jet or Ebony, or pin-up calendars. These dazzling pieces are both tidy and careful, yet strangely unpredictable, as if Simpson had allowed the process of excising the female silhouettes to approach automatic drawing rather …

June 8, 2021 – Review

Maysha Mohamedi’s “Sacred Witness Sacred Menace”

Fanny Singer

I cannot stop thinking about the quality of Maysha Mohamedi’s facture. There are a number of different styles of brushstroke—or, perhaps more accurately, applications of paint—deployed in Mohamedi’s first solo show at Parrasch Heijnen, but, in particular, there is one type of line, thin and febrile, that struck me as completely original. It’s unusual to discover something like this in contemporary abstract painting; young artists are inevitably rearranging, for the most part—sometimes brilliantly—familiar, anthologized marks. There is a sense that only a finite quantity of maneuvers are possible when it comes to the meeting of pigment and surface. Here is a line, however, rendered in oil with a minute brush, that denies the sumptuousness of the medium. A line that, in effect, does what oil paint does not want to do: it creeps anxiously across a spare ground, it does not fatten, grow tumid with thinner, or spill blearily beyond itself. As if responding to my scrutiny, this line appears—on each canvas applied at different frequencies—to jump like the reading of a seismometer’s jittery needle during a series of minor earthquakes, or, in other places, to accumulate like a loose mass of Silly String. I think of Joan Mitchell, her …

April 22, 2021 – Review

Ishi Glinsky’s “Monuments to Survival”

Christina Catherine Martinez

It was an emergency. A young brown girl had Tik Tok’d misinformation about the origins of punk. A podcast was assembled. A white expert was brought in. He used to skateboard. He said the girl was “probably a good person” but she didn’t know what she was talking about. A Reddit post began with a list of black and brown punk artists (Pleasure Venom, Big Joanie, Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex) and the thread spiraled into a tangled argument over whether or not they constituted the “real” origins of punk. I can’t believe these arguments are still happening. But then again, I’m still not certain I know what modernism is, only that it has failed us in some way, and I know that similar arguments occur about whether what we call “America” today started with brown people or white people, and what value judgements must attach to each tangled story.

Sitting on the ground in the back room of Chris Sharp’s white cube gallery, Ishi Glinsky’s Tohono O’odham Basket (2013) looks like a tangle of wires shaped into a gourd-like vessel, a purposeful twist on the traditional baling wire baskets of his tribe. Each of the five works in this …

February 10, 2021 – Review

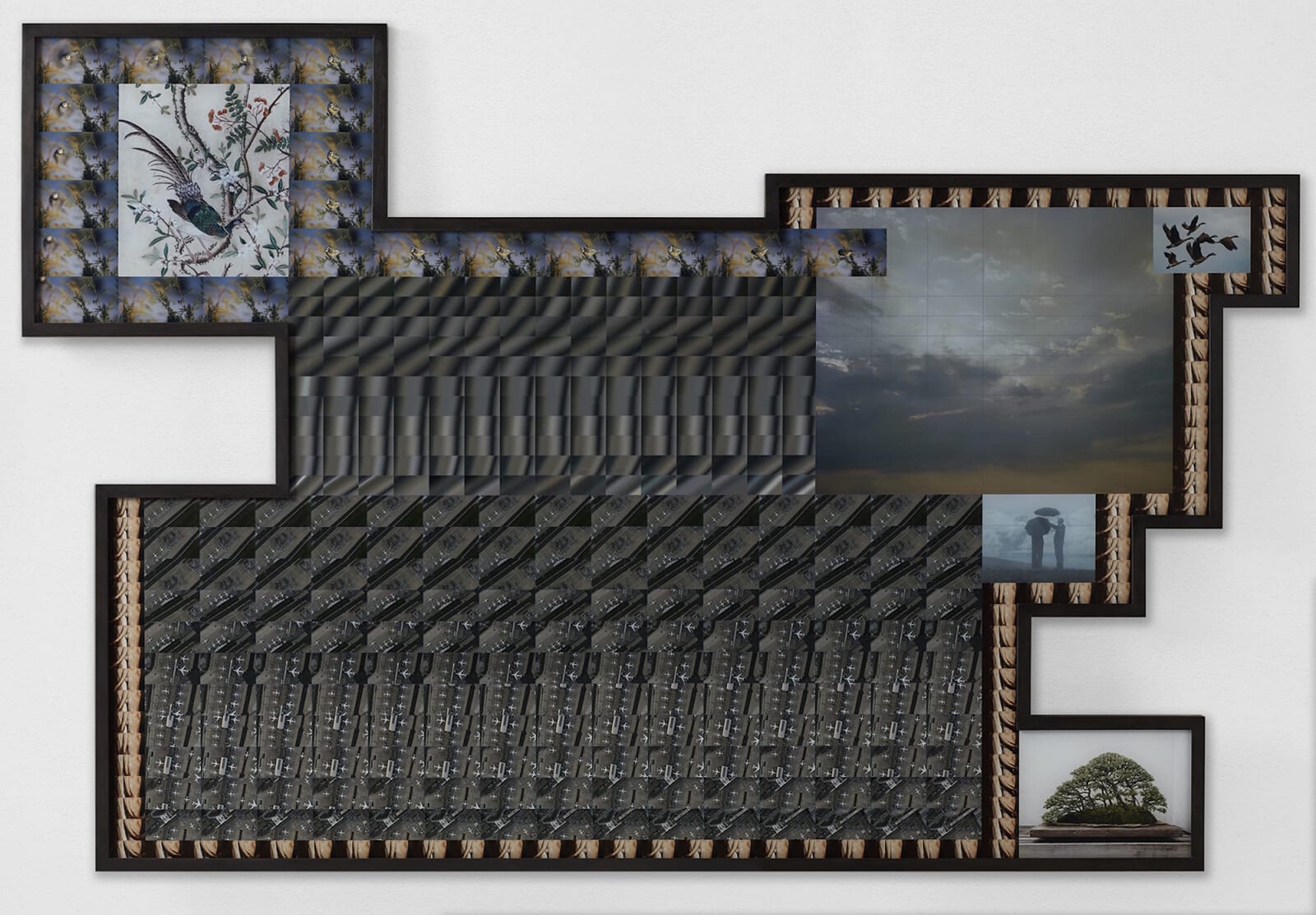

Liu Shiyuan’s “For Jord”

Fanny Singer

As I left Liu Shiyuan’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, I kept tripping over lines from a Robert Hass poem, “Meditation at Lagunitas”: “because there is in this world no one thing/ to which the bramble of blackberry corresponds,/ a word is elegy to what it signifies./ […] After a while I understood that,/ talking this way, everything dissolves: justice,/ pine, hair, woman, you and I.” This poem was published in 1979, when the internet as it exists today wasn’t so much as a dream, but the dissolution that Hass describes is in many respects the subject of Liu’s forensic examinations of post-internet culture. Since 2007, the Beijing-born Liu (who splits her time between China and Denmark) has devoted herself to unpacking, interrogating, even satirizing, internet semiotics. At a moment in history in which an ever-increasing percentage of the global population has been compelled online, there is a poetry to Liu’s search for meaning in a digitally atomized world.

Liu’s exhibition is centered on a fictional—and purely conceptual—character named “Jord” (after whom, or what, the show is titled). Jord is both a noun and a name in Danish, translating, respectively, to “land” or “soil,” and “divine being” or “peace.” …

February 4, 2021 – Review

Jeffrey Gibson’s “It Can Be Said of Them”

Patrick J. Reed

Here’s a platitude: all’s fair in love and war. This, one could argue, is what Jeffrey Gibson’s solo exhibition “It Can Be Said of Them” is all about: the love being queer love, the war being that waged against queer bodies of color who cannot voice their desires without anticipating, so as to deflect, hatred. Here’s a second platitude to consider in relation to the first, one sometimes assigned to Gibson’s artistry: it is infused with joy and resistance.

It’s true that both characterize, for example, YES! WE CAN (all works 2020), one of two punching-bag sculptures at the gallery’s center. White and yellow words reading “CAN THEY SHE HE DO IT? YES WE CAN!” wind around the bag in a red-and-blue square diamond lattice. As one circles the hanging piece, it reveals its pronouns deftly, like jabs to the psyche that parry normative presumptions. This sensation carries through to the mixed-media pieces mounted on the nearby walls—combinations of acrylic paint, glass beads, and fiber materials embellished with lyrics and protest slogans. The show is a flurry of defensive moves and is more complex than the upbeat language that is often used to label it.

Another of Gibson’s …

November 17, 2020 – Review

“Made in L.A. 2020: a version”

Travis Diehl

The posters advertising “Made in L.A. 2020: a version” show a painting of a tear-filled eye. It belongs to President Obama, a detail from Political Tears Obama by Fulton Leroy Washington, aka Mr. Wash. The work dates from 2008, suggesting that while the rises of Trump and the virus have come to shape how we receive everything, including this abbreviated biennial, causes for anguish predate both. In a series of works on view at the Hammer, Washington’s bright-burning surrealism portrays not only the “political tears” of politicians and celebrities from John McCain to Michael Jackson, but also those of his fellow inmates (the artist spent two decades behind bars after being wrongfully convicted on three drug-related charges), drawing the viewer to reflect on the continuing toll of decades of carceral capitalism in the US.

This biennial, announced in January, installed in June, and previewed by the press in November, still has no public opening date. Several live, performance-based projects, notably those by Harmony Holiday and Ligia Lewis, have taken provisional shapes. As conceived by the curators, Lauren Mackler and Myriam Ben Salah, along with the Hammer’s Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, the show runs recto-verso at two museums—the Hammer and the Huntington. …

October 14, 2020 – Review

Jennifer J. Lee’s “Wallflowers”

Travis Diehl

The eleven compact paintings in Jennifer J. Lee’s “Wallflowers,” all dating from 2020, hang heavily on the white walls of Chateau Shatto, Los Angeles. Each work is around A4 in size and plays with layers of texture and detail, transferring source images of intricate scenes—stonework, crocodile skins, flowers, and seeds—onto an unforgivingly wide-woven jute. The slime-aged arches of Abbey, the blood-orange marble of Elevator, the baked psychedelia of Wallpaper—the unprimed material dims Lee’s colors as if with time.

The pictures are further compressed by their cropping. Couch depicts a sofa, patterned in garden-, bruise-, and fire-hued florals of a boomer vintage: the painting’s rough surface, pigmented and oiled, resembles the coarse upholstery of its subject. It lets slip only the tiniest patch of context—a glimpse of a room—in the upper-right corner. The composition is otherwise foreshortened, the pillowy seams of the cushions and pleats cutting a smart diagonal. In Cathedral, Lee’s rendering of tracery and arcades narrows to a blotchy impressionism, as if through a lens with a shallow depth of field. The canted planes in Wallpaper, Elevator, Records, and Security Mirror similarly place their subjects in the middle-distance.

Each image pushes to the edges of the …

June 10, 2020 – Review

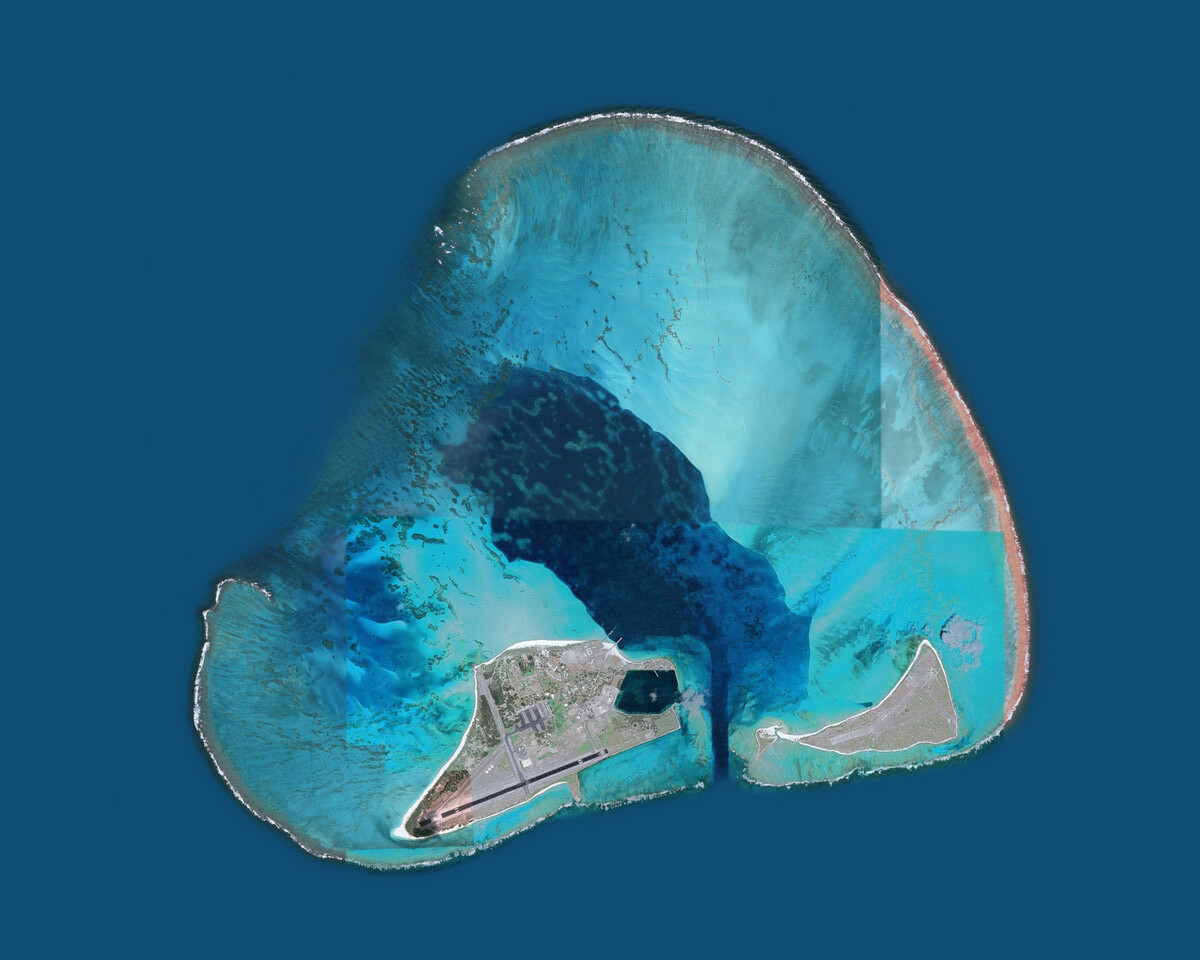

“Unoccupied Territories: The Outlying Islands of America’s Realm”

Patrick J. Reed

At 15°53’N 78°38’W in the Caribbean Sea lies the remote Bajo Nuevo Bank. Population: zero. Formerly claimed by Jamaica and Honduras, this reef and islet cluster is administered by Colombia, though Nicaragua and the US both insist that it belongs to them. Devoid of citizenry, the island is defined by its strategic and economic value to competing nation states.

Bajo Nuevo and ten other islets or atolls comprise a category of US territories known as the Minor Outlying Islands. As the Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI) describes them in “Unoccupied Territories: The Outlying Islands of America’s Realm,” an online exhibition comprising images from Google Earth alongside texts describing the islands, they are the “tattered fragments of [US] dominion.” To the CLUI, a non-profit producing interdisciplinary work at the intersection of art and geography, these unorganized, mostly unincorporated, mostly uninhabited, and sometimes disputed geopolitical fragments demand investigation.

The islands’ histories of abuse by imperial ambition and damage by global war are distinct, but they share absorption into US jurisdiction under the Guano Islands Act of 1856, a federal law that permitted Americans to claim the scantest ocean topography on the premise that it was stateless and held …

February 18, 2020 – Review

Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz’s “Moving Backwards”

Kim Córdova

As I sit to organize my thoughts on Pauline Boudry and Renata Lorenz’s installation Moving Backwards, currently on show in Los Angeles project space JOAN, breaking news alerts slide anxiously across my screen like ephemeral disaster poetry:

Russia closes China land border to prevent spread of coronavirus.

Press Send for Brexit: E.U. Seals UK Withdrawal by Email.

Republicans Block Impeachment Witnesses, Clearing Path for Trump Acquittal.

Netanyahu Plans to Extend Israeli Sovereignty Over Jordan Valley and Settlements.

Boudry and Lorenz’s response to this moment of what they call “reactionary backlashes” is to find power and possibility in backward movement, as a strategy of tactical response. Through a multimedia work featuring, as its centerpiece, a video of a series of dances that play with perceptions of locomotion, the artist duo ask what power could be assumed by disassociating the notion of forward movement from advancement and backward movement with defeat. Put another way, what violence is imposed by a conceptualization of time that is grounded in a colonial understanding of progress as an act of continuous conquest?

Moving Backwards establishes its collaborative …

December 3, 2019 – Review

Lari Pittman’s “Declaration of Independence”

Travis Diehl

Lari Pittman’s resonant retrospective at the Hammer in Los Angeles impresses first with the filigreed intricacy of his paintings, second with their special monotony. Three decades of work spills forth in the bold colors of commercial signage, splashed with decorative motifs—Victorian cameos, arrows, tipping pots, teardrops of various fluids, and the accoutrements of Enlightenment science. The more things change, the more they resemble the past. A carousel or color wheel of eighteenth-century silhouettes rolls through a garden of giant roses in This Amusement, Beloved and Despised, Continues Regardless (1989), as the figures paint on easels or hold measured discussions; a man in the lower right corner exposes his cock. Their human shapes presage the disarticulated dummies or robots that clatter across the compositions of the series “Grisaille, Ethics & Knots” (2016), where the colors give way to apocalyptic chrome, white, and warning-light red. Pittman’s paintings reiterate a history of individual styles: all-over expressionism, minimalist structure, constructivist design, mannerist embellishment, and, emulsifying all, postmodern pastiche.

Still, the dense chemistry of each individual painting burns through the overall clutter. The chronological hang at the Hammer delivers an increasing avalanche of strokes and stencils, but also reveals the tight interplay of small differences …

June 26, 2019 – Review

Eliza Douglas’s “Josh Smith”Eliza Douglas’s “Josh Smith”

Christina Catherine Martinez

When I took a fiction workshop in community college, the professor had a rather solemn habit of handing everyone’s manuscripts back to them with a gnomic phrase of critique or encouragement. He’d stop at your desk, plop the thing down, and say something like “you’re not delivering the goods” or “the text is incorruptible” and the rest of the class would blush or cringe in empathy. One day he lingered in front of Matt, uncharacteristically nonplussed, before gently handing over Matt’s paper. “I don’t know how else to say this,” he said, “but…lesser writers spend years trying to figure out how to write this badly.”

The rest of the class looked at one another, unsure of whether to laugh with Matt or at him, or ourselves.

Looking at Eliza Douglas’s work brings up all of this. Her paintings are awkward but somehow cool, deadpan but not cynical, unskilled but self-aware, surfeit with gall but not bravado. Douglas embodies an elusive up-to-the-second vibe, the je ne sais quoi of late-capitalist modernity, found also in the flat, sure-footed prose of Natasha Stagg, the low-register vocal fry of the girls of the Red Scare podcast. It’s a kind of affectlessness. (While writing …

March 29, 2019 – Review

Suzanne Jackson’s “holding on to a sound”

Jennifer Piejko

Suzanne Jackson was drawing two lines by 1968: One she traced over and over in watercolors and oils and strange new acrylics, of wingspans and the receding landscapes of her adolescence; the other was a limit, drawing a boundary against a relentless decade and the demands of her contemporaries.

Her lines intersected at Gallery 32. Sectioning off half of her live-work studio in the Spanish-style Granada Buildings in MacArthur Park, Jackson handed the floor over to her classmates and teachers from the then-nearby Chouinard Art Institute (which has since merged with CalArts) and Otis College of Art and Design, including David Hammons and Charles White. She also hosted fundraisers for the Black Arts Council, Watts Tower Arts Center, and Black Panther Party, as well as “Sapphire Show” (1970), the first survey of black women artists in Los Angeles. Evidence of this history is on view in the foyer of O-Town House, a new gallery located in the Granada Buildings, just a floor above and a half-century behind the original Gallery 32. Folds of handwritten invitations, curling photographs, price lists, exhibition announcements, and contact sheets fill a line of vitrines, laying out an ephemeral context for the exhibition of Jackson’s works from …

September 11, 2018 – Review

Vincent Fecteau

Fanny Singer

Nature has a habit of reproducing its best engineering––why reinvent the circuitry of veins if you have their blueprints in the roots and branches of trees, in the shapes of rivers flowing from tributaries? Fractal patterns are iterated everywhere: in succulents, cauliflowers, snail shells. Vincent Fecteau’s sculptures, too, feel borrowed from natural forms such as grottoes and caves. In fact, there is something rather grotesque about them: organic nooks and stalactite-like shapes coalesce into liminal, terrestrial landscapes.

In the main room of Fecteau’s current solo exhibitions at Matthew Marks’s Los Angeles space, four sculptures sit on plinths ringed sparsely by four wall-mounted collages while a second, smaller gallery brings together a single sculpture with a single collage (all of the works are untitled). Collages previously shown in 2014 at Marks’s New York gallery are reunited with others from the same period, and brought together for the first time with sculptures made for an exhibition at Vienna’s Secession in 2016. The juxtaposition of pieces from different moments and contexts affords the viewer an opportunity to consider how Fecteau’s two dominant mediums––which can read as distinct conceptual and formal strands––have been in critical dialogue over the last several years.

In his 2014 exhibition at …

August 31, 2018 – Review

Fernando Palma Rodríguez

Jennifer Piejko

The coyote nods to himself, self-assuredly, keeping his eyes steady while his body shifts balance—the motion sensors make his gaze relentless. He brushes his limbs back until he is resting on his hind legs, bracing for a gallop. He retreats, his tail is taut, his front paws are winding up—literally—to ensnare his prey. The kinetic animal in Soldado [Soldier] (2001), an angular cardboard head leading a red metal sketch of a body, can be a stand-in for its creator, artist and engineer Fernando Palma Rodríguez. In the Uto-Aztecan language Nahuatl, the coyote is a mythological animal that fluctuates between wild and civilized states, entering and exiting each side of the divide with sensitivity. Nahuatl tradition also tells us that the heart, yóllotl, has the same etymological root as motion, ollin—and that this dynamism is the defining characteristic of what it means to be alive. Sentiment plus movement equals life. Collapsing both variables, the coyote conceives his own life through reactive animation.

Moving past the anxious canine that paces the first level of House of Gaga / Reena Spaulings, Coatlicue / Xipetotec (2018) guards the entrance to the next level. A nearly blank visage with a fleshy mouth rests on top of …

July 2, 2018 – Review

Made in L.A. 2018

Jonathan Griffin

Not so much a city as an unevenly populated, multi-centered megalopolis, and not so much a year as a point in an escalating concatenation of national and global crises, there might seem to be no possible way to get “Made in L.A. 2018” right. Add to that the divisions within LA’s art community that mirror many of the historically entrenched divisions within the city itself—between east and west, north and south, white and non-white, gentrified and gentrifying, young and no longer young, left and far left. If artists, as “Made in L.A. 2018” curators Anne Ellegood and Erin Christovale write, are “some of our most active citizens,” then biennial curators might be something akin to well-intentioned politicians, expected to represent a plurality of impassioned positions while trying also to retain sight of their own.

Against these odds, Ellegood and Christovale have succeeded in organizing an exhibition that is hard to fault, in large part because of their scrupulous avoidance of curatorial overreach. While Hamza Walker and Aram Moshayedi’s “Made in L.A. 2016” (pretentiously subtitled by the four-word poem “a, the, though, only,” and including multidisciplinary contributions both inside and outside the museum) was clearly intended to stretch the possibilities of its …

May 15, 2018 – Review

Chris Kraus’s "In Order to Pass: Films from 1982–1995"

Patrick Steffen

Dear Chris,

How sweet it was talking with you at the opening of your show. You allowed me to introduce myself, so I could share some words I have longed to tell you since I arrived in this city. I was introduced to Los Angeles through your writings: a primal, unfettered education in the local art scene; I know it well enough now that my interest has begun to wane. I feel like Gravity—the main character in your film Gravity & Grace (1995), one of nine on view at Château Shatto—when a stranger rests his head between her legs and she stares into the void, seeking something meaningful, relevant, eternal. The way you edited that scene—the way you edited your entire filmography—reflects the way you write. You speak the way your characters speak.

I hear your voice throughout these films. Formally, they range from documentary—such as Voyage to Rodez (1986), in which you recount an episode in Antonin Artaud’s life, and Traveling at Night (1990), about a field trip to a deconsecrated Wesleyan Methodist Church in Darrowsville, New York—to fiction. Sadness at Leaving (1992), for example, is based on Erje Ayden’s 1987 autobiographical novel of the same name, about his time as …

May 11, 2018 – Review

Peter Shire’s “Drawings, Impossible Teapots, Furniture & Sculpture”

Andrew Berardini

Los Angeles is an unruly city. Under shaggy palm trees and the bruised purple blooms of jacarandas, roads snarl in mile upon mile of naked asphalt and concrete lined with buildings from every conceivable shape and era. Mostly there are low-slung, postwar ranch houses and bungalows with yards swollen with succulents alongside patches of grass, strip malls with packed parking lots under a patchwork sign advertising dozens of shops, hawking everything from soul food and vegan tacos to Thai massages and pot dispensaries in three different languages—and all of it, caught at dusk, wearing the rich, smeary colors of smog-smothered sunset. Then again, tucked between the hills and highways, you’re just as likely to find fruit orchards and high-rises, marble palaces and shantytowns. All over, things jut and stick out. The brash cacophony of visions and the tucked-away secret gardens make up a city that is both a mess and a dream, constantly resisting just about anything you can say about it and existing like Venice in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (1972), as every city and none. You might hate it, but LA has got style. And few artists capture its gleeful and garish, brash and beautiful resistance like Peter …

April 16, 2018 – Review

Dave Hullfish Bailey’s “Hardscrabble”

Travis Diehl

Like a thesis hidden in a footnote, a small projection in one corner of an exhibition of junkyard complexity shows a loop from John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), starring John Wayne and James Stewart. In the scene, Stewart’s character, a lawyer in the frontier town of Shinbone, sits before a schoolroom full of kids and adults. He’s learnin’ them readin’ and writin’, where no one else will. He is also, lawyerly, teaching them about the law of the land, paraphrased thus: “The people… are… the boss!” It is a lesson in the John Ford mold—as self-evident and patronizing as Stewart’s words of praise: “That’s fine. That’s just fine.” The same goes for the film’s plot, which pits the outlaw and rustler Valance against the fence- and property-line-loving townsfolk, who just want to raise their sheep in peace. The film is a latter-day Ford allegory: “liberty,” an old idea, must be gunned down, now that we’ve outgrown untrammeled, unfenced ranges and need regimented “lots,” “towns,” and “ranches” instead. REDCAT being an exhibition space and not a grade school, the viewer is encouraged to be skeptical about the purity of such motivations as the anti-entropic philosophy of manifest …

April 4, 2018 – Review

Charlemagne Palestine’s “CCORNUUOORPHANOSSCCOPIAEE AANORPHANSSHHORNOFFPLENTYYY”

Eli Diner

Marveling over the evolution of his latest exhibition, Charlemagne Palestine remarked: “This idea or obsession that I had with a few animals at the beginning, never did I imagine that it would become such a maximal, enormous work like this. It’s the biggest ever with about 18,000 or more. That we found them quite easily and quickly. And there are hundreds of thousands more out there so it’s like some kind of social phenomena [sic].” The animals are stuffed, and all of them used, or used up—orphans, as inscribed in the title. Together with a variety of props and sounds, they fill the cavernous main gallery at 356 Mission, which has played host to some of the most ambitious exhibitions in Los Angeles over the past five years and which last week announced that this show would be its last. Palestine’s précis provides the key markers for navigating his mesmerizing, heavily Instagrammed, carnivalesque installation: magnitude, the bounteous resource, the obsession “at the beginning,” and some kind of social phenomenon, though what kind exactly is the question for us.

Together with orphans, two horns of plenty appear in the title, both in English and Latinate formulations, plentitude making a fine watchword for …

March 28, 2018 – Review

Los Angeles Gallery Share

Jonathan Griffin

At least Condo, in London and New York (and soon also Mexico City and São Paulo), and Okey-Dokey, in Düsseldorf and Cologne, had snappy names and branding. The latest manifestation of the increasingly popular gallery share model, hosted by three Los Angeles galleries, does not have a name. Its program, in which eight international galleries and one peripatetic “off-space” have descended on Hannah Hoffman Gallery, Kristina Kite Gallery, and Park View/Paul Soto for the month of March, seems to have evolved very organically. One might even call it ad hoc.

Such a low-key approach may not necessarily be such a bad thing, indeed might even amount to an ideological and/or aesthetic stance, except that it also conveys the impression that nobody involved really expected anyone to talk about it much, or—especially—to write about it.

So, why am I? Firstly, because the endeavor occasioned the display of some very good art, much of it previously unknown to me. And because gallery shares are a format that is becoming increasingly common, and will only get better if we take them seriously, critically. Also because such declarations of international allegiance between galleries are nearly always comment-worthy, especially when they converge on Los Angeles, which, …

February 7, 2018 – Review

pascALEjandro’s “Alchemical Love”

Andrew Berardini

For true mystics, there is no division between the real and the spiritual. The symbolic folds into our lives, shaping the world and us in it. The cool kiss of rain can be a curse or a blessing from the gods. Stumbling in the street en route to meet your lover might signal deeper misgivings and potential pratfalls of your coupling. Rather than a pseudoscience, astrology can, in tracking the paths of celestial bodies, chart our hidden natures. The card flourished from the tarot deck for many unveils the true shape and contour of a life: its past, present, and future. To practitioners and adherents of the esoteric, the interior and the exterior, the natural and the supernatural are one. “As above, so below,” to quote the legendary father of alchemy, Hermes Trismegistus.

Drawn by filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky and colored by costume designer/artist Pascale Montandon-Jodorowsky, the drawings that make up “Alchemical Love,” conceived and realized by this married couple (under the portmanteau of their two first names pascALEjandro), reveal a world of magical forces shaping their lives, a spirituality that weds the deeper mysteries to their love story. They are deceptively simple, each strange scene almost pulled from a children’s book …

November 3, 2017 – Review

“Dysfunctional Formulas of Love”

Jonathan Griffin

If your first associations with Colombia are cocaine, paramilitary violence, and the rapacious plunder of natural resources by neo-colonialist corporations, then you are only half right, according to this spirited, unkempt, and organizationally flawed exhibition of Colombian artists at The Box, Los Angeles. Along with all these clichés (eagerly resold to Western audiences through film and television), Colombia is a society of familial warmth and communal resilience, a place where humor, love, and magic play important roles in the survival of its people.

Curators Víctor Albarracín Llanos (who is Colombian) and Corazón Del Sol (who grew up there) allow all of these narrative threads to entwine through the work of 32 artists, most of whom live in Colombia but some of whom now reside elsewhere. One is Los Angeles-based Gala Porras-Kim, who fled Colombia when she was a child, packing hastily in the middle of the night after her family was threatened. The small trove of items she brought with her is arranged on a low table as an untitled and undated installation: comics, letters, some dried leaves, and a cheat sheet for Mortal Kombat 3 (1995). Collectively, the objects reaffirm a tired narrative of dysfunctional Colombian life, but individually they …

November 1, 2017 – Review

Elaine Cameron-Weir’s “wave form walks the earth”

Andrew Berardini

The medieval wardrobe of a sadomasochist, the secret torture chamber gear of a conflicted superhero, grim relics of gods from the deepest abysses of a broken dimension, or, as they truly are, artworks, sparsely hung, dangling from ropes, splayed like bodies, and rippled into curtains of parachute silk, with one emanating scent (as has become a regular ritual in Elaine Cameron-Weir’s exhibitions). Here it’s the ancient aroma of freshly warmed labdanum cooking in a laboratory heating element.

Nearby, cast pewter breasts and belly dangle from the fine mesh of a long-sleeved chainmail hauberk, shouldered with leather harnesses, a long, thin metal tube spreading the arms in prayer or supplication, all hanging in the air with industrial pulleys anchoring it to the hard cement floor with a cinched sandbag. The scenography of the last bit makes it feel like a prop in some lost play by H. P. Lovecraft costumed and propped by H. R. Giger. A sinister future or distant present, the clandestine fetishes hidden in the dungeon of our collective psyche. A fucking awesome costume to a really sick goth party.

The artist lends her voice to the curious titles of these works—the hauberk’s named dressing for altitude (2017)—but even more …

July 10, 2017 – Review

"At this stage"

Travis Diehl

Where to begin? Where else but at this stage? A cotton boll embalmed in a bell jar like the Disney rose in Beauty and the Beast (1991): Aria Dean’s Dead Zone (1) (2017) gives the rose’s place to a white commodity once harvested by black people made commodities. The cotton stands there like a badly conserved museum piece that still reeks of shame. But there is a current charge, too: viewers can take their photos, but they’ll have to wait to post them. Under the bell jar’s oversized base, Dean has hidden a signal jammer modeled on the ones Beyoncé’s bodyguards use to scramble any cell phone in the star’s radius. We are at the stage where a celebrity needs military-grade technology to stage-manage their image—and meanwhile in the ongoing spree of police murdering black Americans, video evidence earns no justice, only spectacle.

Dean’s is the first piece inside gallery Chateau Shatto for this summer of 2017; this is a topical group show, and the topic is a gut check of American exceptionalism. At this stage! The phrase suggests a sequence, a disease—progression, if not progress—like the shot holding on a film of a skyscraper in Sturtevant ‘Warhol Empire State’ (1972). …

June 9, 2017 – Review

Brian Bress’s “In Lieu of Flowers Send Memes”

Andrew Berardini

Here’s the latest Spring menswear line worn by the hottest male models of the twenty-eighth century, those jaunty scions of cyborg overlords. Our wetwear bodies found a hardware durability after we and our machines, long flirting, finally coupled. Moodily lit with mint and hot pink, humanoid bods sport flight jackets and tennis togs and fencing uniforms with patterns like alien cryptography, their sculptural faces as interchangeable as their clothing. Once the singularity curves past us, why wouldn’t we change our faces at will? Who needs a mouth when we can communicate telepathically, plug in for nourishment? These head-sculptures angle with Bauhausian geometries and deco motifs, the curves of Incan spaceships and patterns of ancient Greek friezes. All of it soft and foamy. Even cyborgs yearn for a little pliability. The models gently revolve on screen, giving us the whole fit, a catwalk turn, even as those bods stay otherwise still in their languorous revolutions. Nearby, the heads of these on-screen models sit on plinths in all their bend and ornament, ready for a discerning consumer to find the expression that fits their fast-paced cosmic lifestyle, a new head for a new season.

Brian Bress has long been casting characters and creatures …

April 25, 2017 – Review

“Concrete Island”

Travis Diehl

Word on the street is they got the Crenshaw Cowboy. Into a gallery, that is. Anyone who has turned onto the westbound I-10 at Crenshaw Boulevard has likely noticed him, an itinerant junk-assemblage artist who shows his sculptures at the top of the onramp. He also gives advice on fame and creativity, by way of hand-painted signs—for example, on a curling particle board: “Go into Your Own Creative Mind You are The Master Of Your Thoughts And Behavior. If Anyone Stress’s [sic] You Out… You Allowed it… You’re not a Robot Okay : ) Smile.” Five of these signs appear in “Concrete Island” at Venus, Los Angeles, a show that, by way of J.G. Ballard’s novel of the same name, romances the aesthetic of those who eke out a living in the city’s gaps.

Of the 31 artists and collectives included, only the Crenshaw Cowboy is homeless. Indeed, a wide gulf separates the rush-hour panhandler from the gallery artist. Add to this the fact that Venus’s polished square footage is part of an archipelago of new galleries gentrifying the warehouse district of LA’s Boyle Heights. The homeless there have been pushed out; nearby homeowners may soon join them. Perhaps the inclusion …

April 18, 2017 – Review

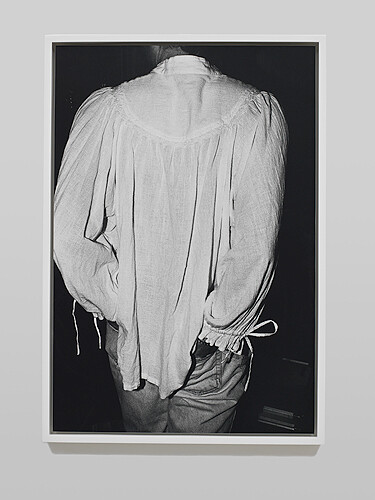

Malick Sidibé’s “Chemises”

Jennifer Piejko

Only someone with a lying mouth, according to Yoruba oral tradition, would speak first and look for visual confirmation second. Untold centuries later, the expression retains its value: photography’s maneuvers depend on the fact that truth is determined by the eye.

The complete history of photography is inextricable from colonialism in Africa—its establishment, rule, and dismemberment. The practice was introduced on the continent almost immediately after its invention, disseminating quickly. Some of the very first silvery daguerreotypes captured Egypt’s grand wonders in the 1840s; by 1853, African-American Augustus Washington had opened Liberia’s first studio in the capital Monrovia, and Senegal’s by 1860. The medium was slower to spread into Yorubaland, taking up until Britain’s drawing of modern-day Nigerian and Beninese borders at the turn of the twentieth century, but the photograph was folded into both ancient custom and contemporary society so neatly that it expanded beyond document and into identity architecture. The staged portrait was a highly orchestrated image, a manifestation of oriki, the Yorubian ritual of lauding someone’s character by making them a subject of praise poetry: a man during odo (midlife) sits alone in traditional dress at the very center of the frame, facing the lens, with a vertical …

March 15, 2017 – Review

Judith Bernstein’s “Cock in the Box”

Sabrina Tarasoff

There is no image more prescient of modern displays of masculinity and status than Judith Bernstein’s drawing COCK IN THE BOX (1966), inspired by a history of Vietnam-era bathroom-stall graffiti. Whether those lewd sketches were made to parody politics in wartime, as comic relief for those on the john, for camaraderie, or to alleviate boredom, the big boy’s room provided a space to think patriotism through masculinity. Perhaps Lyndon B. Johnson’s characterization of the penis as a tool to leverage force was an influence: one anecdote has the president, plagued by reporters asking why the United States was in Vietnam, unzipping his pants, pulling out his flaccid cock and saying: “This is why!” No more poignant example of power mislaid.

Such sentiments surely lingered on the mind of Judith Bernstein as she drew COCK IN THE BOX midway through Johnson’s six years in power as US president. The charcoal and pastel drawing opens her exhibition at Los Angeles’s appropriately named The Box, setting a tone of equivocation between politics and entertainment—a timely commentary considering the farcical climate of the United States’s incipient despotism. The sketch is a smudged pastel of a sweetly pink dick sprung from a star-spangled jack-in-the-box. Beneath a …

February 22, 2017 – Review

Terence Koh’s “sleeping in a beam of sunlight”

Jonathan Griffin

Over the decade and a half of his career to date, Terence Koh has generated so many myths that it is now nearly impossible to begin thinking about his work without first acknowledging the tales of his personal and professional decadence in New York during the pre-crash mid-aughts, or the story of his apparent atonement when he faded from hypervisibility following his 2011 show “nothingtoodoo” at Mary Boone, New York, retreating with his partner to a mountaintop in the Catskills. The legend is threadbare from retelling; you’re at a computer—if you don’t already know it, Google him. Better, instead, to start with some facts about Terence Koh in 2017.

On the roof of Moran Bondaroff gallery in West Hollywood, Koh has built a beehive with a door big enough for humans to crawl inside. Above a mesh screen, teeming live bees build honeycomb between wooden slats. The hive—titled bee chapel (2017), the third he has made after a prototype in the Catskills and a version for his 2016 exhibition at Andrew Edlin Gallery, New York—stands on a rustic wooden platform perhaps six feet high, beside a temporary rooftop garden. Lavenders, sages, yarrow, fruit trees, leaf vegetables, and herbs grow in pots, …

January 6, 2017 – Review

Paul Thek

Jennifer Piejko

There is no more poetic organ than the human heart: a blood-soaked snarl of muscle tissue whose constriction is our literal life force, its cadence—its pulse—has been held accountable for not only bodily function but as the instrument of conscience, intention, love, and courage; a spiritual and corporal engine. The Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore grasped its virtue on both planes when he mused, “That I want thee, only thee—let my heart repeat without end;”(1) W.H. Auden composed a number of verses over his concern of the amiss desires and capacity of a crooked one. Pre-Columbian Aztecs extracted it, still beating, as a sacrifice to the Sun God; for Roman Catholics, divine love radiates from the Sacred Heart of Jesus—and may it set ablaze all of ours with His love and mercy.(2)

Paul Thek—supermarket attendant, artist, occasional expatriate, diver—was raised Catholic. The work he made in his shortened lifetime, before dying of AIDS-related illness in his mid-fifties in 1988, often displayed a carnal sympathy toward entropy and (its) beauty, intimately embellished, longingly ritualistic—catholic in the comprehensive sense, and anything but devout. Visiting the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo with his lover Peter Hujar, Thek fell into a macabre exhilaration, wandering through the 8,000 …

December 6, 2016 – Review

Isa Genzken’s “I Love Michael Asher”

Travis Diehl

In a shallow bay window facing 2nd St., a ledge overflows with studio clutter: a couple dozen euros in coins between a few dying plants; a bowl filled with loose earrings and studs; a keycard from the Waldorf Astoria; a castle of used tea candles, Red Bull cans, and tiny uniformed figurines (cops, or Luftwaffe), all iced with white paint. One only wants the empty blue ashtray to overflow with butts to complete the quintessential image of an artist at work. The setup doesn’t just mimic; nearly every object has been shipped from Genzken’s studio in Berlin, down to the ledge itself. The extant window has been remodeled and a radiator sourced to match the original. (Genzken’s actual desk is here, too. So is a reproduction of a studio wall.) Her process has seemingly been frozen, portioned into discrete pieces, and mailed to L.A.

The collages and assemblages, accordingly, are laced with the leftovers of art handling, packing and unpacking; one trio of works is laid out on their boxes; several pieces include tape marked with the D’ART® logo of a transatlantic shipping company. (All works are from 2016 and, except where noted, untitled.) Other sculptures feature German shopping bags. An …

November 2, 2016 – Review

Marnie Weber’s “Chapel of the Moon”

Andrew Berardini

During the day, Halloween masks look pretty cheesy. Hanging from the drugstore rack’s seasonal aisle under the terrible clarity of fluorescents and the afternoon sun, it’s hard to image these killer clowns and fat-cheeked Frankensteins frightening anyone. Their warped faces and weeping pustules, yellowed horns and sharpened teeth, all a static, cartoonish fakeness crinkling in the soft latex.

But they do frighten, only in the right place. Or better yet, they let fright happen.

Night shadows make those masks less costume and more possibility, the cheap details worn away with the darkness. The contrivances of Halloween allow for the playacting of fear and violence, a space and costume to exorcise one’s inner demons by becoming them. And besides all that, the freaks come out at night. Who makes a monster? The feared, the outcast, the othered. Most of us find easier affinity with the monsters than with the pitchforked mob that sometimes chases them.

In the darkened gallery at Gavlak, Marnie Weber gathers a coterie of monsters with stacked Halloween masks under a weeping willow dangling shards of stained glass. Along the walls hang a suite of pagan collages and through a dark doorway church pews face a screening of the artist’s first …

October 21, 2016 – Review

Hanne Darboven

Jonathan Griffin

Rows of numbers instill in me a sickening panic. I got that feeling, familiar from childhood mathematics lessons and annual tax returns, in Hanne Darboven’s current exhibition at Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles.

Perhaps there was no need for such histrionics. In 1973, the West German Darboven told the writer Lucy Lippard that her art has “nothing to do with mathematics. Nothing!” For Darboven, numbers were a means of marking out time and space, “writing without describing.” For the most part, her work is not as concerned with calculation as with counting. Numbers, written sequentially, are akin to seconds ticking on a clock, days counted on a calendar or beats in a piece of music. (Indeed, in 1979 Darboven developed a system of musical notation which she used until the end of her life, in 2009, to write compositions for chamber orchestras and string quartets.)

Darboven’s work generally consists of gridded pages of annotations and numerical inscriptions, sometimes handwritten, sometimes typed or printed; in 1978 she began including collaged elements such as her photographs and cuttings from books. In a single work, these pages can number in the hundreds or thousands. On the ground floor of the gallery, the staggering Erdkunde I, II, …

July 22, 2016 – Review

“a, the, though, only,” Made in L.A. 2016

Andrew Berardini

I’ve lost all my pride

I’ve been to paradise

And out the other side.

With no one to guide me,

Torn apart by a fiery wheel

Inside me.

—The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band’s “I won’t hurt you” (1966), heard in Laida Lertxundi’s Vivir para Vivir / Live to Live (2015)

In LA, everyone’s Marlon Brando’s gardener. Cruising through a city sold and resold as a promised land, we’ve nothing to guide us but our passions for prosperity, for fame, for space, for spirit. All of us here somehow find a place in the end, even if it’s only as workers in others’ gardens, Edens owned by those that cast our dreams in moving pictures and the developers that sell or rent us our own smallest bite of paradise.

Made in L.A. 2016 is almost explicitly not about Los Angeles, though the city’s still the set.

Everyone likes to look in the mirror sometimes, and a localist biennial has some vanity for sure, but the city’s self-regard (Los Angeles again playing itself, to riff on gay porn auteur Fred Halsted through cine-essay maker Thom Andersen) has been finally outpaced by others’ regard for it. Such biennials can easily be read as a trend report for …

June 1, 2016 – Review

K.r.m. Mooney’s “Oscine”

Jonathan Griffin

Since it is impossible to say—in the work of K.r.m. Mooney just as in the world—where one thing ends and another begins, it seems appropriate to start by considering the structure that houses this exhibition. An ancient wooden shed, it was once a garage for the large Craftsman home it sits behind, built in 1906. Wide sliding barn-like doors open onto patched timber walls and a cracked concrete floor stained from years of dripping motor oil. Weeds sprout through some of the cracks and papery pink bougainvillea petals blow in from the garden. As a concession to the aesthetic formalities of the white cube, a pristine white rectangle of wall divides the front gallery from the storage area behind.

There are only two artworks on the checklist, though the exhibition—titled “Oscine”—comprises many more parts. A case in point: the first work on the list, Accord, a chord (all works 2016), consists of two small box-like sculptures placed on the floor of the gallery. A diptych, if you like. Their dimensions reminded me of external hard drives or books—dictionaries perhaps. Both allusions are pertinent. As with most of Mooney’s work, each is a combination of modified and crafted elements: in this instance, …

May 4, 2016 – Review

Robert Morris & Kishio Suga

Stuart Munro

Words, like the gray matting in Robert Morris’s Lead and Felt (1969/2016), are woven. Yet, like these felt strips, descriptions shift. In a shared context with Kishio Suga’s Parameters of Space (1978/2016), material and form take on meanings that bend, twist, and track the local climate. The immediate world provides a particular field of reference, the imperfect translation of one language into another. Moving between objects positioned by hand, you can’t help but be aware of their interest in borders and boundaries.

Lead and Felt was originally made for an exhibition at Castelli Gallery in New York, after which it was lost and then remade. Morris came to interpret L-shaped lead and felt strips in later life as an echo of another work created for the show, Scatter Piece (also 1969), that also went missing. Whether exhibited, stored, or thrown into some distant landfill, they became an expression of how transient objects are and how resilient an idea can be. The original Scatter Piece is buried somewhere in New Jersey, casting what Morris describes as a “shadow” over later iterations.

Parameters of Space was made for Kishio Suga’s 1978 solo exhibition at Gallery Saiensu, in Morioka. His interest in borders was laid …

March 8, 2016 – Review

Seth Price’s “Wrok Fmaily Freidns”

Sabrina Tarasoff

To cut to the chase: Seth Price banks on banality. Bides his time building constructs, rather than content; repeating forms overblown by rhetoric. Most famously, his oft-cited essay “Dispersion” (2002) has served as justification for the material choices made in his career, quoting—nay, preaching—redistribution of existing materials as alternative currency to the creation of new form as dictated by the demands of the art market. But, like items made of reclaimed wood at Crate & Barrel, so altruistic and self-aware in offering a way out from buying into all that “new” stuff being made, so too is Price’s art part careful marketing. What’s for sale seems to be the illusion of escape, or capitalism re-branded and snazzily packaged as an “alternate economy”—books readily available to download online, paintings pushing 200k. Quid pro quo. But in the context of post-1990s New York, as long as you’re self-aware and inclined to irony, double standards seem to be okay: after all, participation with the market is measured only in terms of how self-conscious of it you are, or how eloquently you can copywrite that relationship.

Eloquence, at that, can assume many guises and at Los Angeles’s 356 S. Mission Rd. it appears as Price’s …

March 3, 2016 – Review

David Snyder’s “2THNDNL”

Travis Diehl

Happy? Ronaldreagan. Hungry? Ronaldreagan. Afraid? Ronaldreagan. Invoke him often enough and The Gipper’s name passes from rote signification into a malleable abstraction. All too easy—as David Snyder demonstrates in “2THNDNL” with the video Ronald Reagan, Fathers & Sons (all works 2016). Dozens of jaws, clipped from TV’s talking heads, from Paul Ryan to Barack Obama—sometimes comped below the forehead of another to form a rhythmic exquisite corpse—speak, ad nauseam: “Ronald Reagan.” The syllables slur toward pure intonation. On a wall opposite this video is a second: Swansong, a supercut of snarling dogs. The cacophony, and the numbness that follows, figures our present national discourse. Never mind the gulf between that pragmatic movie cowboy and today’s nativist publicity hounds. Love him or hate him, this is a Reagan even apolitical animals can understand.

Debased rhetoric? Snyder’s got shovelfuls. In a small screening room at the gallery’s center plays The Guano, a lucidly manic pitch to “retrofit” our nation’s thousands of derelict Blockbuster Video outlets as bat colonies—and thus, per Snyder’s voiceover, “fundamentally rebrand and rebuild a Blockbuster empire and comfortably dominate the bat shit industry.” Great news for business. And for the left? It’s true, as Snyder points out, that runoff from …

February 8, 2016 – Review

"Jean Baudrillard’s photography: Ultimate Paradox"

Jennifer Piejko

In “Ultimate Paradox,” swaths of rich, saturated color hang across each of 20 framed photographs. Rust-hued powdery tree trunks overshadow a flittering, out-of-focus leafy green background (Alentejo, 1993), an angle which would have required the photographer to climb several meters into the tree’s branches; the acid-azure knotted tree trunk shot in Vaucluse (1992) matches an overstuffed pillowcase in Paris (1985) and a taut plastic tarp ceiling installed in Rio (1996); the dripping crimsons of two lone cafe chairs planted outside in late-afternoon Luxembourg (2003) mirror the sanguine velvet regally draping an armchair in Sainte Beuve (1987); and the reflection of an orange car buoys upside-down on an inky pond camouflaged by celadon and electric chartreuse lily pads in the gorgeous Brugges (1997), whose delicate floating leaves’ green is picked up in a pair of ragged concrete posts on the shore caked with moss streaks of the same shade in Amsterdam (1992). Titled after the city in which it was taken, each giclée print, screened on pure cotton paper, is empirically visually pleasing, a tasteful selection of aspirational-lifestyle and global-traveler snaps.

Sainte Beuve also covers The Conspiracy of Art, Jean Baudrillard’s 2005 limb-from-limb dismantling of the global contemporary art system. Perhaps his …

February 1, 2016 – Review

Art Los Angeles Contemporary and Paramount Ranch

Myriam Ben Salah

At the risk of immediately doing away with any probity or intellectual credibility whatsoever, I have to confess that the last thing I watched on my computer before landing in Los Angeles was an old episode of “Keeping up with the Kardashians” featuring the over-the-top wedding of Kim Kardashian and Kanye West. Upon arrival at LAX airport, the first thing I saw while leaving the Tom Bradley Terminal was Kanye West himself, tucked in a 400,000-dollar white Rolls Royce blasting tracks from his soon-to-be-released and eagerly awaited album WAVES.

This instant of serendipity reminded me of how Los Angeles is, in the words of Jean Baudrillard, hyperreal—a place that doesn’t allow consciousness to distinguish reality from its simulation. Not by coincidence, and confirming the relevance of the French theorist’s thought to a city such as LA, Chateau Shatto is currently exhibiting “Jean Baudrillard’s photography: Ultimate Paradox,” an exhibition of his own photographic works. The city’s hyperreality seemed to be the overarching theme of both the handful of art fairs taking place around town as well as that of the art itself. Art Los Angeles Contemporary (ALAC), the big-ticket stalwart located in a repurposed hangar of Santa Monica Airport, might be the …

December 21, 2015 – Review

Simone Forti’s "On An Iron Post"

Andrew Berardini

Dear Simone,

Your performances are the jump and splash of a brook, the color of a found leaf, a painted flag wrapping a woman as the river dances around her. At 80, your nimble movements inspire. When I stop to read back about your lifetime of accomplishments and confluences, I can’t help but admire you all the more: learning improvisation with Anna Halprin in San Francisco in the 1950s; trying and moving into your own through the techniques of Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, and Trisha Brown; your presence at the birth of Judson Church; your collaborations with Yoko Ono, La Monte Young, and Terry Riley. Just a few flickers from an enduring and illustrious career. I see all those layers and life here in your videos, objects, performances, deepening the grace of your movements and the susurrus of your words, knowing that such simplicity is not easily won.

In the long, high gallery at The Box, I watched the water crash and shiver over the stones on the monitor in Northeast Kingdom (2015), the headphones sounding a dinner conversation between two men about geography and Vermont. Plucking the headphones off (always like wearing an insect when looking at art), I turned to …

October 30, 2015 – Review

Mike Kelley

Kim Levin

Astute observers in the art world were puzzled by Mike Kelley’s move from Metro Pictures to Gagosian in 2005. It seemed as if he had left a warm and supportive family concern for the cold new world of unfettered late capitalism. In the wake of the artist’s 2012 suicide, there was further bewilderment when his estate moved to a different mega-gallery, Hauser & Wirth. Why on earth, wondered my editor when she commissioned this review, would they move from one international blue chip gallery to another?

This posthumous exhibition at Hauser & Wirth provides one answer. Organized in cooperation with the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts and former MOCA curator Paul Schimmel, now director of Hauser & Wirth’s new Los Angeles branch, the show is revelatory: smartly put together with love, insight, and admiration. They knew exactly what to show, how to show it, and how to give it context and sense. They even tried to cast a hopeful light on Kelley’s dark vision. Speaking at the press view, Schimmel said Kelley was dealing with an “epic otherworldly pursuit and the surrealist tradition.” His “sculptures of the unconscious” were “recycling the sense of monumental failure,” seeking “a place to go …

October 16, 2015 – Review

“The Avant-Garde Won’t Give Up: Cobra and Its Legacy”

Rachel Wetzler

Cobra, a short-lived association of artists based in Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam who published an eponymous journal from 1948 to 1951, has the dubious honor of being frequently invoked as a locus of postwar avant-garde activity in Europe, while its works remain all but invisible outside of the group’s native northern Europe. The two-part exhibition “The Avant-Garde Won’t Give Up: Cobra and Its Legacy,” split between Blum & Poe’s New York and Los Angeles locations, aims to be a corrective to this invisibility, as well as to the dominant understandings of Cobra as merely a Situationist precursor or, worse, a minor regional variant on Abstract Expressionist and Informel painting.

The first half of the exhibition, in New York, is a historical survey primarily comprising works from the 1940s and ’50s. It opens with Cobra member Asger Jorn’s painting L’avant-garde ne se rend pas, from which the exhibition takes its title. Part of his 1962 series “New Disfigurations,” found flea-market canvases overlain with childlike doodles and gestural marks, it is a vulgarized portrait of a young girl, redolent of Biedermeier kitsch, to which Jorn has added slightly menacing stick figures and, in a pastiche of Duchamp, a moustache. The titular slogan, scrawled …

July 31, 2015 – Review

Willem de Rooij’s “Legal Noses”

Jennifer Piejko

Brown is a composite color, made by combining complementary hues—a warm neutral. It’s only itself when contrasted with a brighter shade; fuschia or aqua always appear so, while brown is brown only in comparison to another color; its visibility is dependent on the color next to it. Over centuries, brown’s association has changed from one with poverty and drab rusticity to virtue and wholesomeness—softly wrinkled brown paper bags for simple school lunches; the conscientious consumer opting for brown rice or sugar or toast over white; unrefined, unbleached napkins.

Beige. Elegant and dispassionate, beige has the warmth of brown and the coolness of white, and, like brown, is often dull—a background shade. Another chameleon, its perception is mediated by what’s adjacent; its temperature is unstable.

The seven wall works in Willem de Rooij’s new exhibition are each one part of a tangram, a simple Chinese puzzle in which this family of shapes come together to form a rectangle, or one of 6,500 other possible outcomes. First marketed in Germany in the late nineteenth century, they were often carved from stones or imitation earthenware, similar to the color scheme here. Each piece, or tan, is a shape of stretched fabric enlarged to several feet …

July 24, 2015 – Review

Sojourner Truth Parsons’ “I Got Allergies”

Andrew Berardini

The soothing whispers of the song drift beneath the shift and chatter of the opening party like a lavender mist, velvety fingers. The next door gallery was open but not opening. Empty, its harsh white lights beam like a drugstore. But here, the light is softer. Everything is softer.

Ooh baby / yes ooh baby / When we’re out in the moonlight / Looking up on the stars above / Feels so good when I’m near you / Holding hands and making love.

“Baby” by Donnie and Joe Emerson isn’t officially part of Sojourner Truth Parsons’ first solo exhibition in Los Angeles (itself only the second show at the newly-opened Phil Gallery). But, hearing it on repeat during the opening, its sad longing and gentle desires reveal her aesthetic too perfectly to ignore, soundly shaping the various collage paintings, the ebbing video, and curious sculptures. Written and recorded by the teenage Emerson brothers on a farm in 1979, their record sold only a few copies, and its expense almost bankrupted their family. A collector purchased a thrift store copy in 2008 and, thirty years later, Dreamin’ Wild (1979) became an underground sensation covered by LA cult hero Ariel Pink, who described “Baby” …

February 2, 2015 – Review

Art Los Angeles Contemporary, LA Art Book Fair, and Paramount Ranch Los Angeles

Andrew Berardini

No one intended it to begin with assfucking and passed out hippies. But there it was.