Studentship

This collection of essays reframes studentship as a liminal state of transformation. Students hold the grim distinction of simultaneously being the consumers, byproducts, and sine qua non of education. Why are we treated as passive bodies filling enrollment quotas when we play an active role in shaping the institution and generating social change? Our transitory position has been refracted and exacerbated by the pandemic’s effect on higher education. To be a student is to represent uncertainty, potentiality, futurity, a time to come when inequity is rectified. We want to do that work together.

I don’t believe that there is any other aesthetic premise than freedom, as much personal as collective. As this is also an ethical premise, I don’t believe that one can detach aesthetic premises from pedagogical methodologies. In reference to art, leaving aside any precise definition, I understand that it should be a universal form of expression, since every action should be aesthetic and everything should be creative. The opposite is neutral and stagnant. I understand that there is no “anti-art” but, if anything, there is an “other-art” with the same rights and validity.

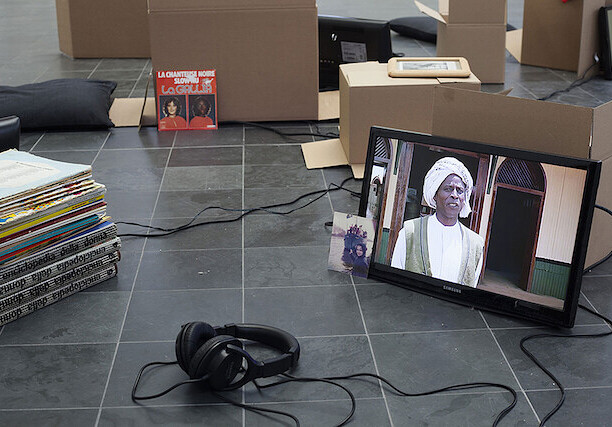

“Who keeps the cube white?” is a crucial question asked by activists at Goldsmiths who are currently protesting for better working conditions and pay for cleaners at the school. For the generation of art professionals coming up now, the activism of groups such as Decolonize this Place and Gulf Labour Artist Coalition is of immense importance. The art organization Khiasma, based in the town of Les Lilas in the suburbs of Paris, aims to decolonize social relations through art by presenting challenging exhibitions and programs that pose questions about what and who produces space. Today, with neofascism acquiring greater visibility and power, intersectionality is a crucial framework for dismantling the power structures of race and gender within institutions. Practices of accountability, care, and mutual respect across hierarchical departments and job positions should be at the forefront of art institutional discourse today. At the same time, we must be wary of the appropriation of intersectional methodology by the very power structures it is intended to combat; as sociologist Sirma Bilge has written of the academic appropriation of intersectionality in the US, it can easily fall prey to the neoliberal “management of neutralized difference in our postracial times.”

WEB.jpg,1600)