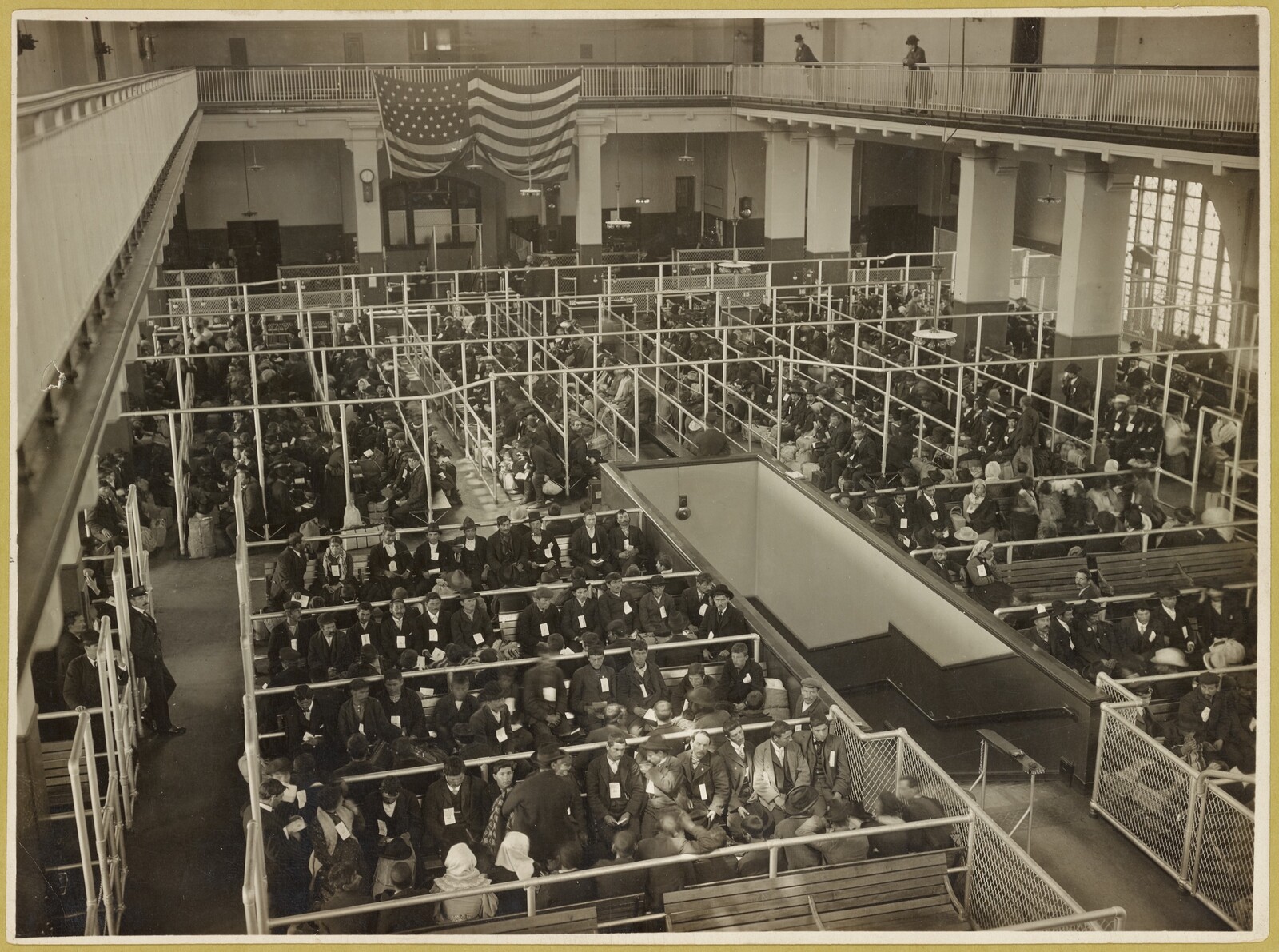

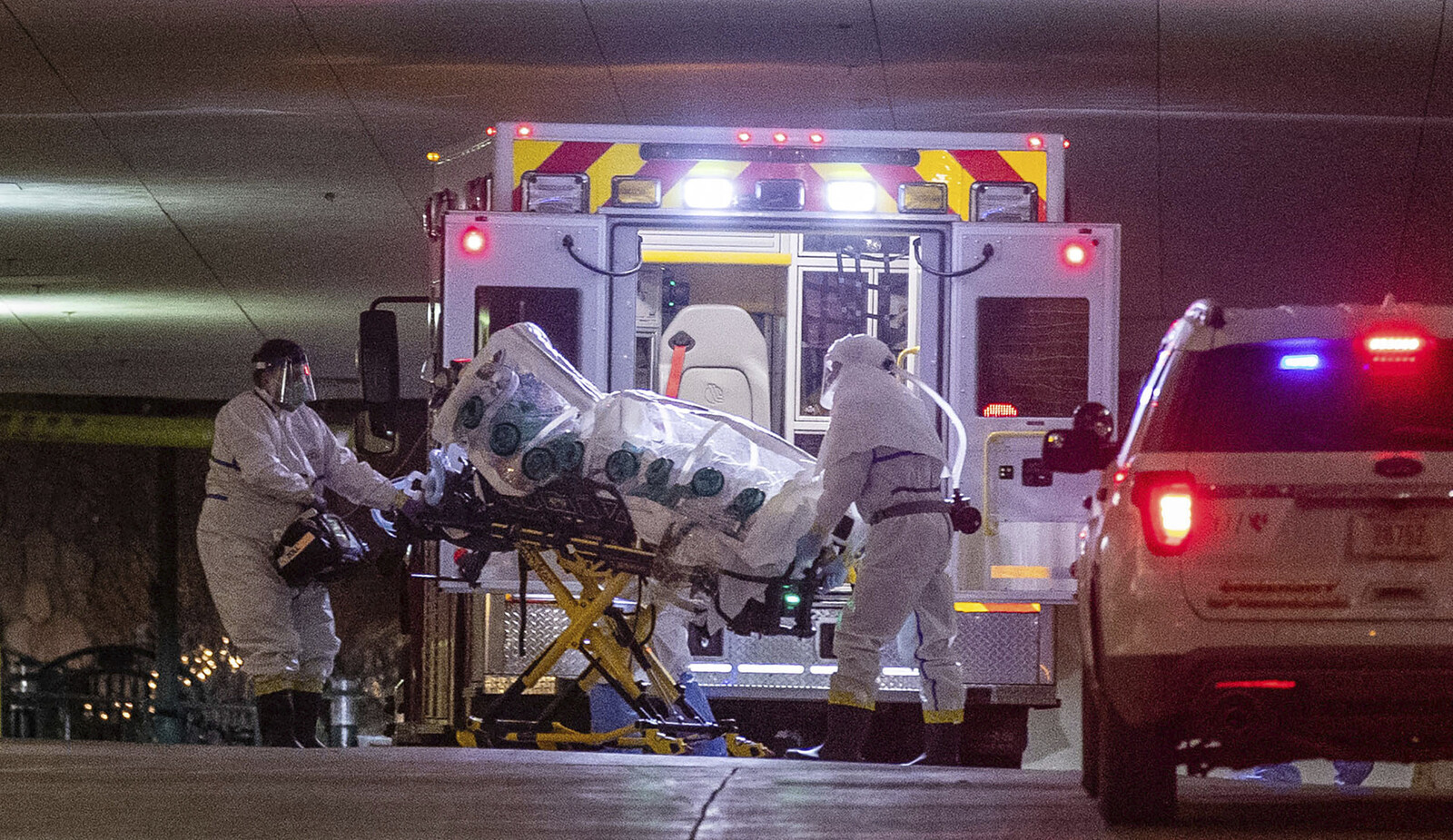

With the early twentieth century development of a series of immigration stations, quarantine facilities, and hospitals at the main ports of entry to the United States, the architecture of the border became medicalized. Between 1900 and 1950, New York was the main destination for working-class immigrants entering the United States, with over twelve million people being inspected at Ellis Island.1 Although Ellis Island is only a single site in the vastly distributed border apparatus, it embodies the complexity of the entire immigration system, and is a space where ideas of modernity, health, race, and class became simultaneously juxtaposed. At the Ellis Island Immigration Station, architecture enabled an immigration process based on racialized and classed ideas of the healthy body.

Through a mediatized spectacle, Ellis Island shaped the way the US public came to view immigration. Written press of the time carried out significant coverage of the Immigration Station, and the Island itself was open to visitors, even being called an “amphitheater” by the New York Times.2 The medical processes that took place on Ellis Island were particularly publicized, given certain prejudices of the time that certain immigrants were more likely to import contagious disease or have a weaker physical and mental condition than others.3

The medical process also dictated Ellis Island’s architecture. The Island’s screening routines created dehumanized, impersonal, and industrial spatial regimes of circulation that allowed unhealthy and undesirable working-class immigrant bodies to be identified and segregated from the healthy and desirable ones.4 Within the expanse of two decades (1900–1920), the immigration inspection center of Ellis Island became an assembly line of medical assessments, entangling the social construct of the healthy, productive, and morally pure body, while the process of screening became part of the definition of the US citizen.

The Creation of the Ellis Island Immigration Station

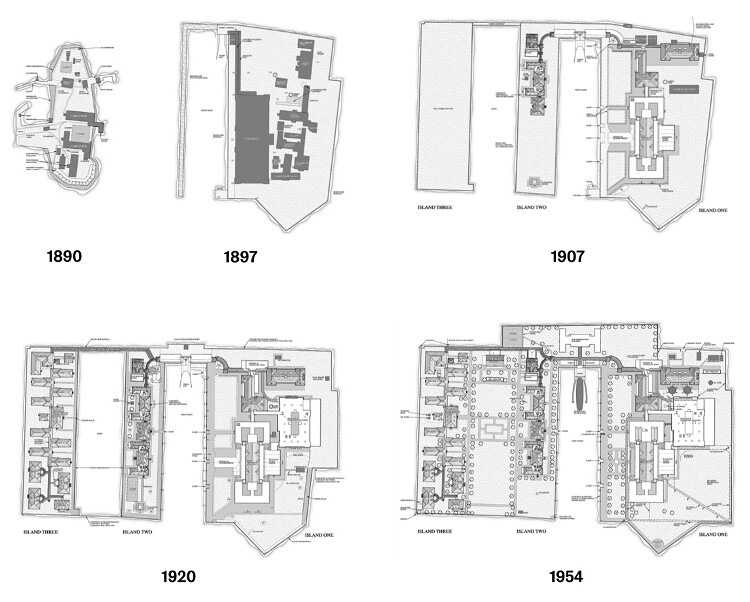

For many years, Ellis Island was a natural island, its only manmade intervention being a small naval powder magazine from the Civil War. In 1892, an immigration station was built, only to be destroyed by a fire in 1897.5 Following this, the Federal Government released funds for a newly designed building that involved the enlargement of the Island’s land mass—from an islet to a man-made, squared-off island able to accommodate the new immigration station, a hospital, a kitchen, and a dining hall.6 The New York-based architectural office Boring & Tilton won the federal competition with a design that integrated a beaux-arts historicistic style with modern space-integrating industrial materials. Ellis Island grew exponentially over the following decades, together with new immigration laws and procedures.

The process of design and construction of the new Ellis Island Immigration Station took two years. During the peak immigration period to the United States, between the 1890s and 1920s, the US Public Health Service was concerned with the spread of contagious diseases during the process of immigration, which often brought many bodies from different places in close proximity to one another.7 Architecture was therefore used as a means of guaranteeing proper airflow, social distance, and other hygienic measures. The Great Hall—the central space where new arrivals were inspected and sometimes held for hours—for instance, could fully renovate the hall’s air in fifteen minutes, using a combination of mechanical air extraction and gear-operated windows. Railings throughout the Station “[formed a] network of the aisles, in which the immigrants are placed in alphabetical order, according to nationality.”8

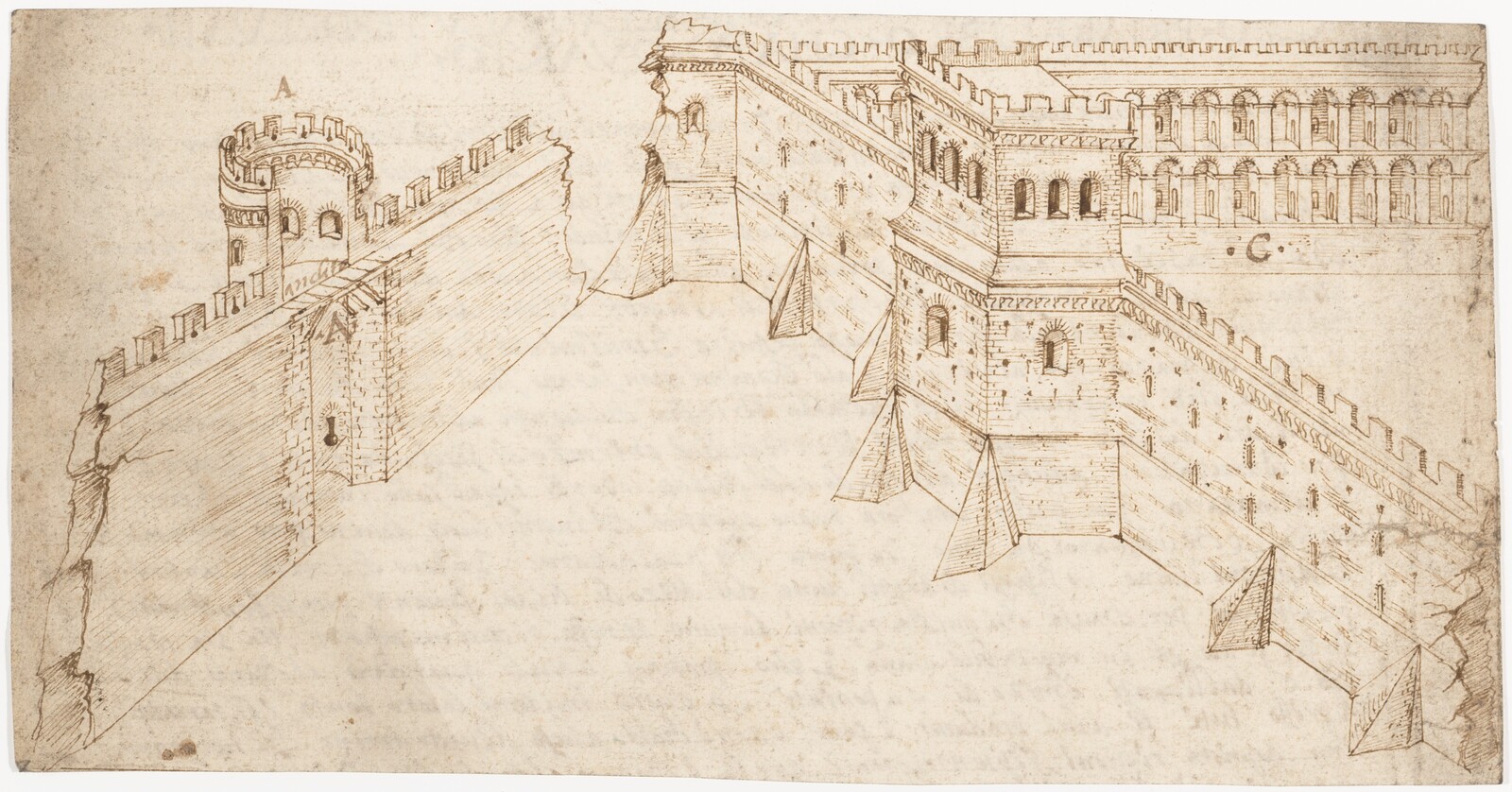

Historical development of Ellis Island as an immigration station. Source: Library of Congress.

Hygiene was not only an element of the architectural design, however; it was also part of the function. A bathing house was designed, “where 200 immigrants can be bathed at a time, 8,000 being about the number that can be thus refreshed during an ordinary day.”9 An Assistant Commissioner of Ellis Island was quoted to have said: “We expect to wash them once a day, and they will land on American soil clean, if nothing more.”

Arrival

For the majority of Ellis Island’s new arrivals, the immigration process, its structures, and systems began many weeks before and many miles away from the new Immigration Station. In the 1900s, private steamship companies performed their own medical checks on travelers at the ports of their origin to avoid carrying sick individuals, and to prevent being held liable for the cost of passengers’ return journeys if they were deported for medical reasons. The immigrant’s steamboats had also first and second-class cabin passages reserved for US citizens and other travelers already admitted to the US. Once the boats arrived in New York, they were initially anchored in the New York Lower Bay, where Public Health Service (PHS) physicians examined the first- and second-class passengers for possible contagious diseases such as cholera, plague, smallpox, typhoid fever, yellow fever, scarlet fever, mealies, and diphtheria. US citizens that used these steamboats for transatlantic passage were excluded from this check, and very few passengers from the first and second classes were sent to further inspection when they arrived on Ellis Island.10

After PHS medical inspectors finished their examinations, the steamships moved towards Ellis Island. Once they arrived, the first- and second-class passengers, previously processed on-board, could head to the Ferry station in Ellis Island and purchase their ticket to New York. Meanwhile third-class passengers were taken for medical examinations at the Immigration Station. After stepping ashore, third-class immigrants passed through an “imposing private entrance, made as nearly as possible free from the observation of the curious” and poured into a waiting area in a pergola connected to the Station. Here, the first medical examination was carried out, in which doctors used a metal hook to flip open the immigrant’s eyelid in order to look for traces of trachoma, a highly contagious eye disease.11 If any evidence of this disease was found, the doctor used a piece of chalk to mark the immigrant with a “T” on the front of the right shoulder.12

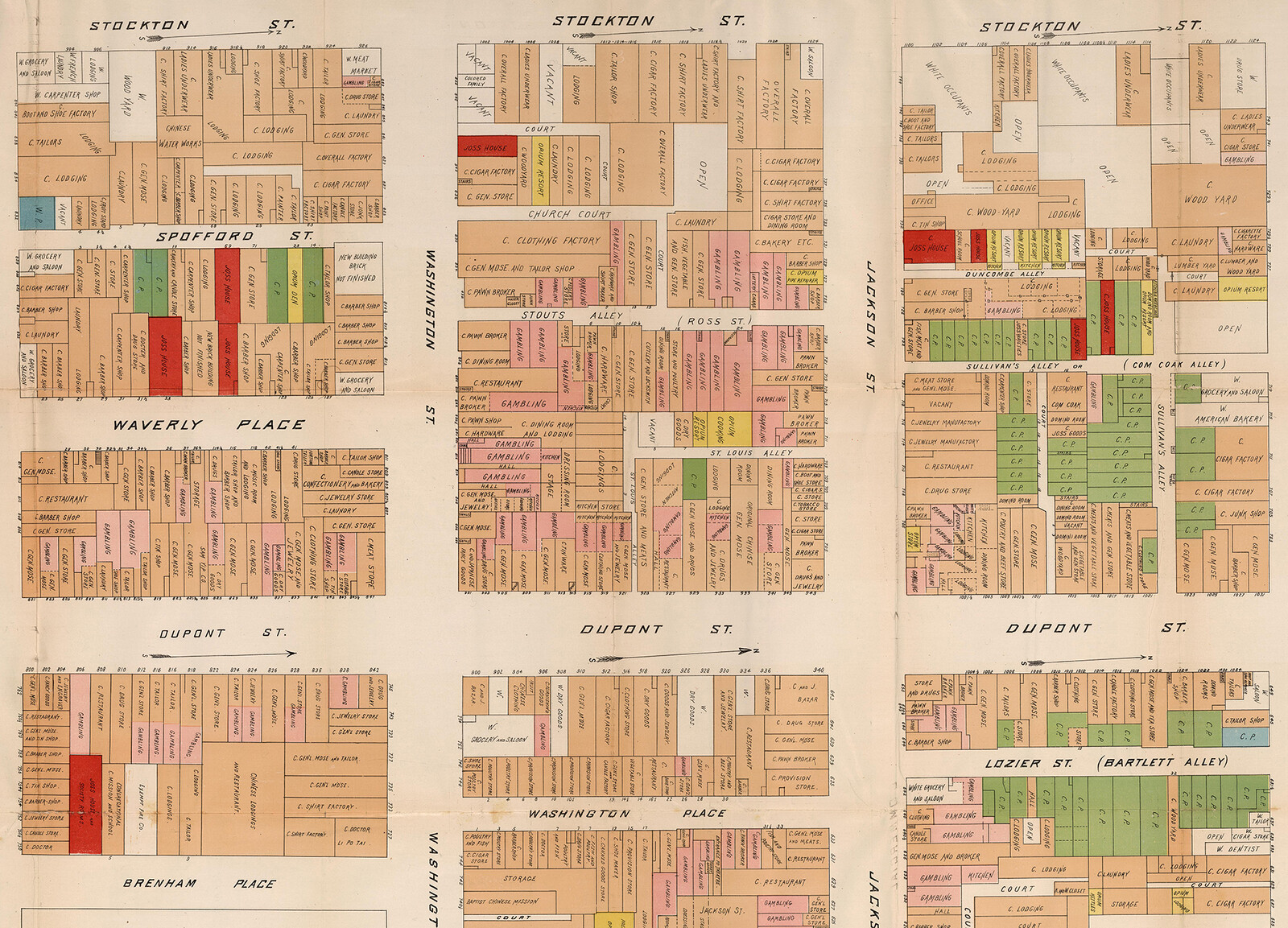

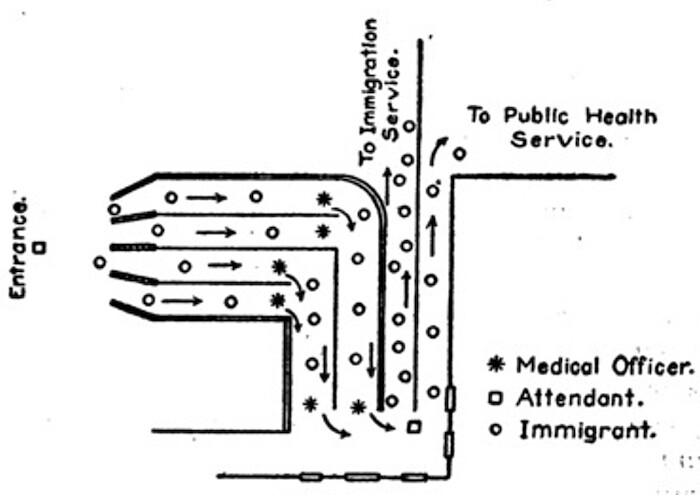

Spatial diagram of the medical inspection at Ellis Island by E.H. Mullan, Surgeon, United States Public Health Service.

Source: E.H. Mullan, “Mental examination of immigrants: Administration and Line Inspection at Ellis Island,” Public Health Reports 32, no. 20 (1917): 734.

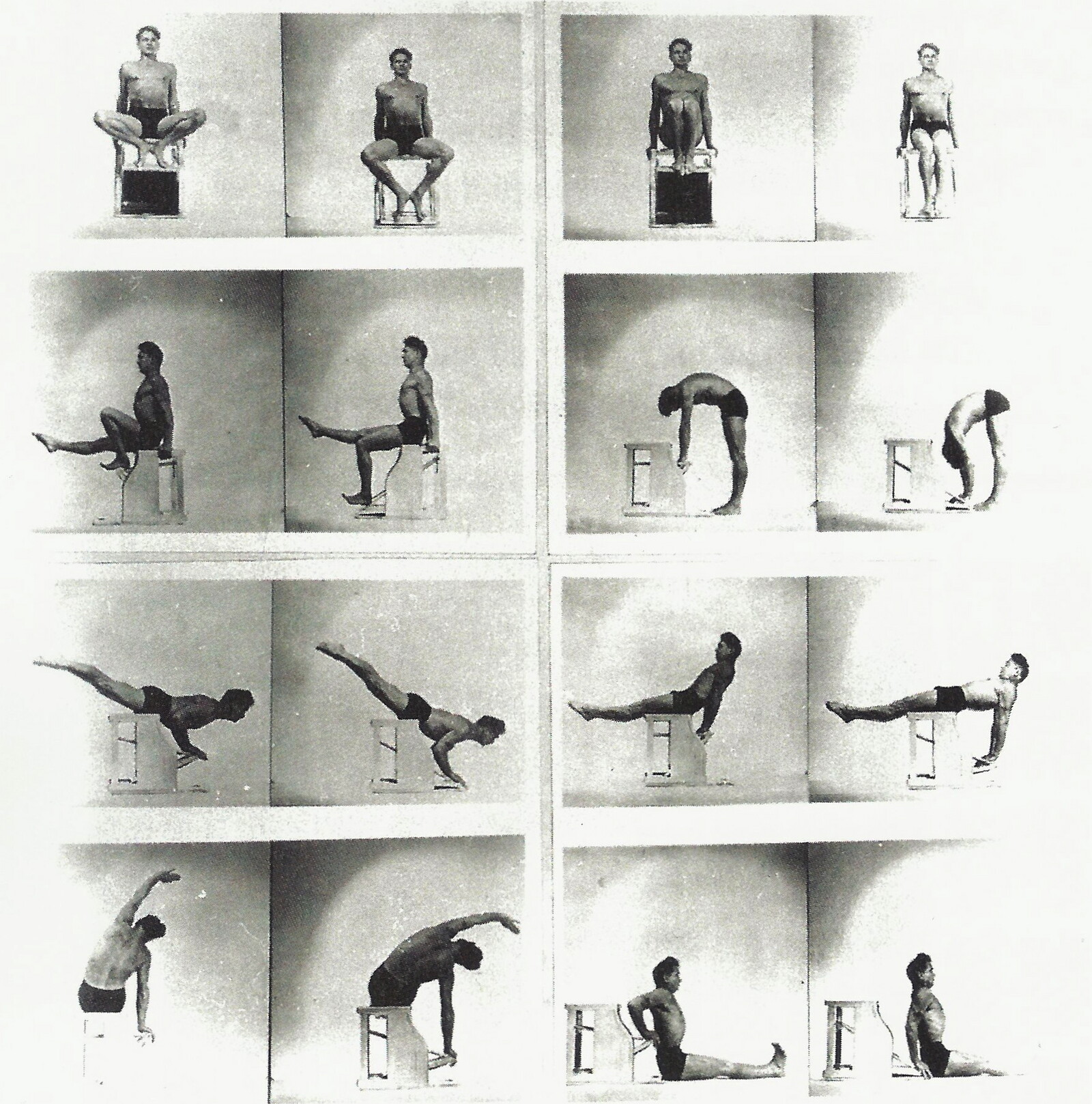

After the trachoma check, the flow of immigrants was bifurcated into two aisles as they moved into the Station: those with trachoma traces would take the right-hand lane, and those without would take the left-hand one. Those suspected of having the disease would then be led towards the Station for further medical checks, and would ultimately either be sent to the Contagious Disease Hospital—if they could afford it—or deported.13 The immigrants considered free of trachoma took a route towards the Great Hall (also known as the Examination Room), which involved climbing from the dark and low ground floor up a steep stairway into the Hall’s voluminous bright space. Although they did not realize it, upon climbing up the stairs, a second medical test was being performed, with a doctor standing at their top watching for signs of lameness, or heavy breathing that might indicate a heart condition.14

Emigrants in “pens” at Ellis Island (probably on or near Christmas, given the decorations). Photograph by Underwood & Underwood, ca. 1906. Library of Congress (Control No. 2012646352).

Entering the Great Hall

The Great Hall was the most important space in the immigration screening process. It was also the most modern room in the whole complex. Large and centrally located in the building, industrial metal trusses and pillars, similar to the ones that were used in railway stations at the time, liberated the brick façade from any load and allowed thirty-six-foot-high windows to be placed on all four sides of the room. This structural operation also liberated the floor plan to operate as a multifunctional space where the immigrants’ paths of circulation and segregation could be recombined and reshaped depending on medical and immigration requirements, as well as the number of people to be examined.

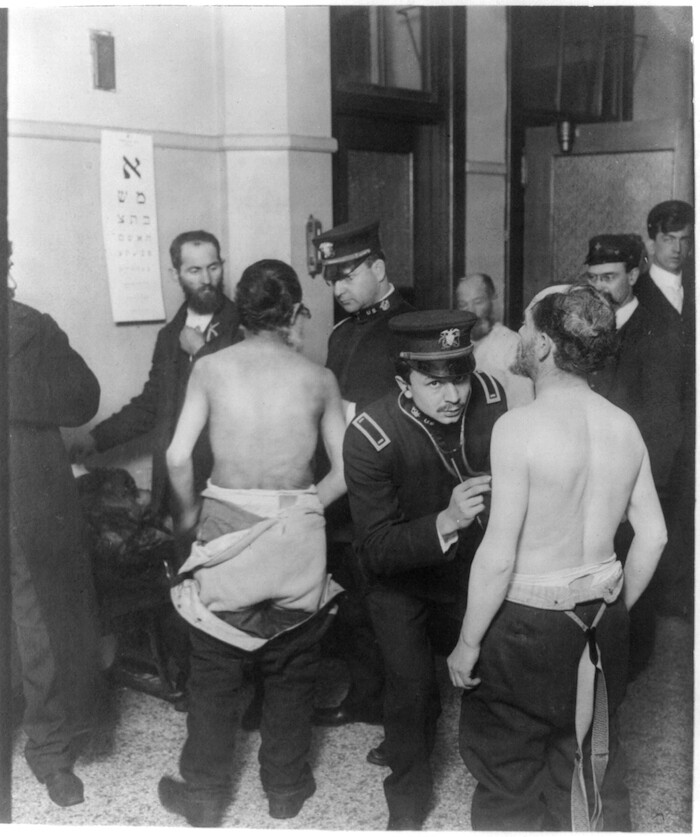

As they entered the Great Hall, the immigrants were segregated by nationality into different aisles. In contrast with the heavy-looking Beaux-Arts exterior, the aisles in the Great Hall were built with lightweight metal pipes and chicken-wire.15 The metal aisles were easy to change and reshape and could be adapted to fit segregation rules as they changed over the years. Here, immigrants waited, sometimes for many hours, seated in cage-like conditions for further medical examinations. The protocol to segregate the new arrivals by nationality emphasized the PHS’s belief that disease was linked to specific immigrants’ origins.16 When called for inspection, populations of certain places of origin—such as the Mediterranean or Eastern European, which were not perceived to be part of white America at the time—profiled to be more likely contagious, or feeble-minded, and thus subjected to more exhaustive inspections.17

As with the previous medical examination processes in the pergola, the ones that took place in the Great Hall were enabled and normalized by the Immigration Station’s interior architecture. As immigrants were called to be examined, they walked through aisles that zig-zagged across the Hall in a way that facilitated the physicians’ work. As the 1907 Book For Instructions recommended, the aisles made two right-hand turns to enable the PHS officers to check both sides of an immigrant’s face and body and facilitate the detection of deformities or disease.18 As the weary immigrants marched forward, a doctor examined their face, hair, neck, and hands.19 Following the same protocol as the trachoma check, should an immigrant be suspected of mental defects, the doctors marked an “X” on their shoulder with chalk, and an “X” within a circle meant some definite mental symptom had been detected. A “B” indicated possible back problems, while “Pg” stood for pregnancy, and “Sc,” a scalp infection. If an immigrant received a mark, they were directed to rooms set aside in the Great Hall for further examination.

Approximately 20% of the immigrants passing through the lines of inspection were held for further examination.20 Some of the detained immigrants were then released, and some kept at Ellis Island Hospital if they could be determined as “curable” or not, and if they could afford the cost of treatment.21 Those who were free of disease traces could, however, still be given the label of “likely to become a public charge” if they were considered not able to work and make a living by the Immigration Officials during the medical screening.22 They could, for example, be categorized as having a “poor physique” or “deformities,” both of which could be deemed reason enough for them to be deported.23 Intersecting with eugenicist, racist, and classist ideals of the time, this evaluation of who was fit for work or not allowed some immigrants to be forbidden from entering the US simply due to their race, sexuality, or physical condition.24

Michel Foucault argues that biopower, governance, and cultivation of bodies and populations, is fundamental to modern Western states.25 Part of biopower is to protect the citizens against supposed “abnormalities,” especially those who “pose a threat to the biological heritage.”26 Immigration processes dictated by ideas of race and sovereignty could, therefore, be better understood “through death-function in the economy of biopower,” or what Achille Mbembé called necropower, which more than a right to kill refers to the state’s right to expose people to (social) death, systemic abandonment or other forms of political violence.27 The screening carried out at Ellis Island was therefore never simply about letting certain people in and excluding others on the basis of perceived health, but part of a racialized system that renders many of those admitted, and those already inside, as permanently “unhealthy” and hence a risk to the white citizen body that of citizenship.28

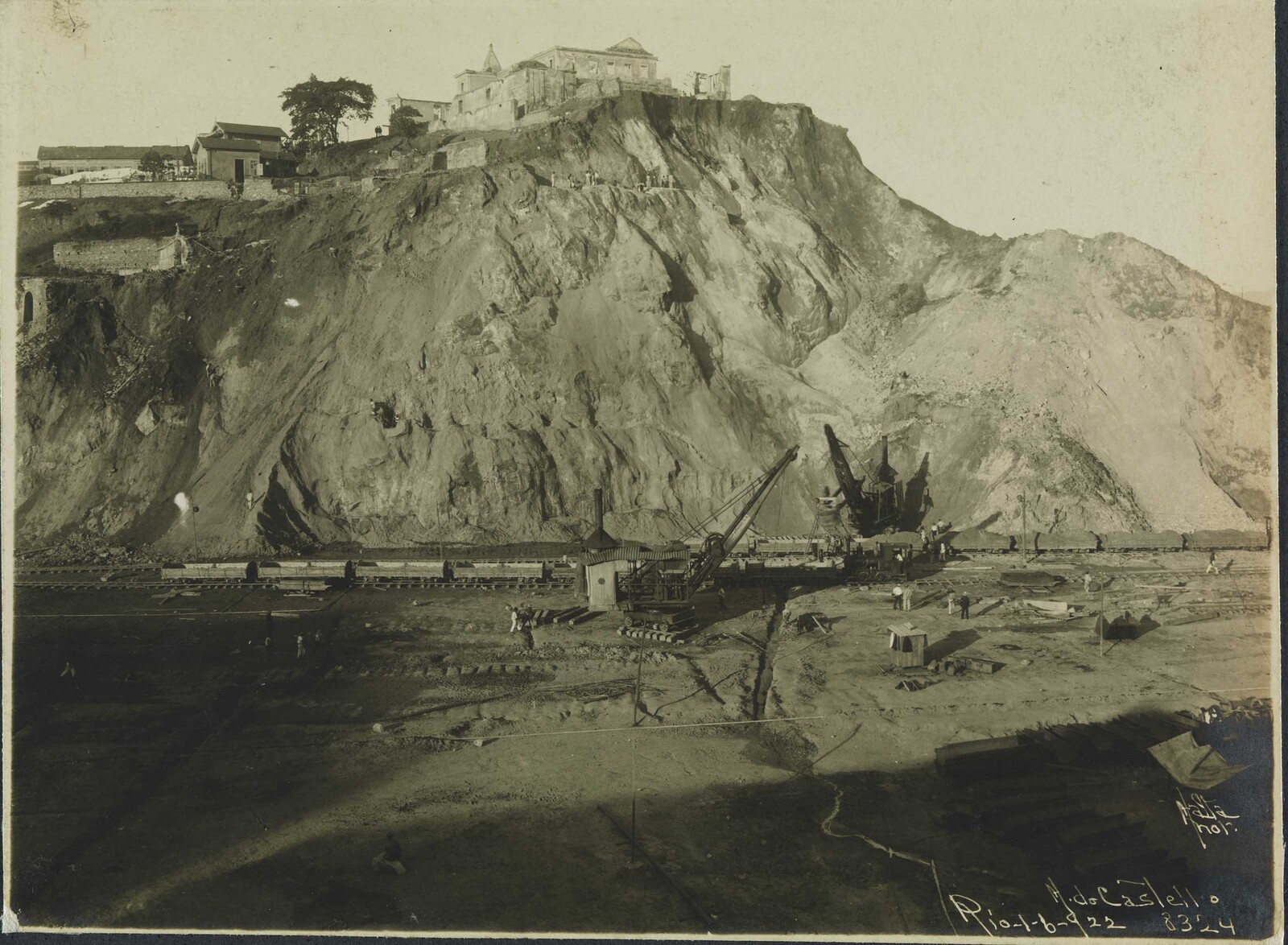

Physicians examining a group of Jewish immigrants; an eye chart using Hebrew characters hangs on the wall. Photograph by Underwood & Underwood, ca. 1907. Library of Congress (Control No. 2012646350).

Divide and Conquer

In 1907, the Treasury department of the USA published the Book of Instructions for the Medical Inspection of Immigrants. This book aimed to categorize immigrants denied entry to the United States on the basis of medical reasons into two groups. “Group A” was described as “Aliens excluded from admission in the country because of disease or abnormal condition,” and was subdivided into “(1) Persons suffering from dangerous contagious disease, (2) Persons suffering from loathsome disease, (3) Insane persons, (4) Idiots.” “Group B” was described as “Aliens, who present some disease or defect, physical or mental, that be regarded as conclusive as an alien ‘likely to become a public charge.’” These “disease or deflect(s)” were subdivided into “(1) Hernia, (2) Valvular heart disease, (3) Pregnancy, (4) Poor physique, (5) Chronic Rheumatism, (6) Nervous diseases, (7) Malignant disease, (8) Deformities, (9) Senility and debility, (10) Varicose veins.”29 The book also provided design instruction, largely informed by that of Ellis Island, on the spatial qualities of inspection rooms and guidelines on how to medically perform the categorization and examination, specifying the desirability of the abundance of light, even surfaces, equally spaced areas, right angles, and systematic plans.

Ellis Island was chiefly formed by physical and organizational structures designed to shape the movements and exclusion of immigrants within these buildings—a materialization of the immigration laws and social constructs that surrounded immigration and disease. The way the land on Ellis Island was specifically shaped and planned for this purpose over the years demonstrates the development of a complex mechanism of control informed by the calculated inspection processes. The Island was transformed into a new, modern environment—one that, in its sublime spaciousness, normalized the medical assessments that took place there.

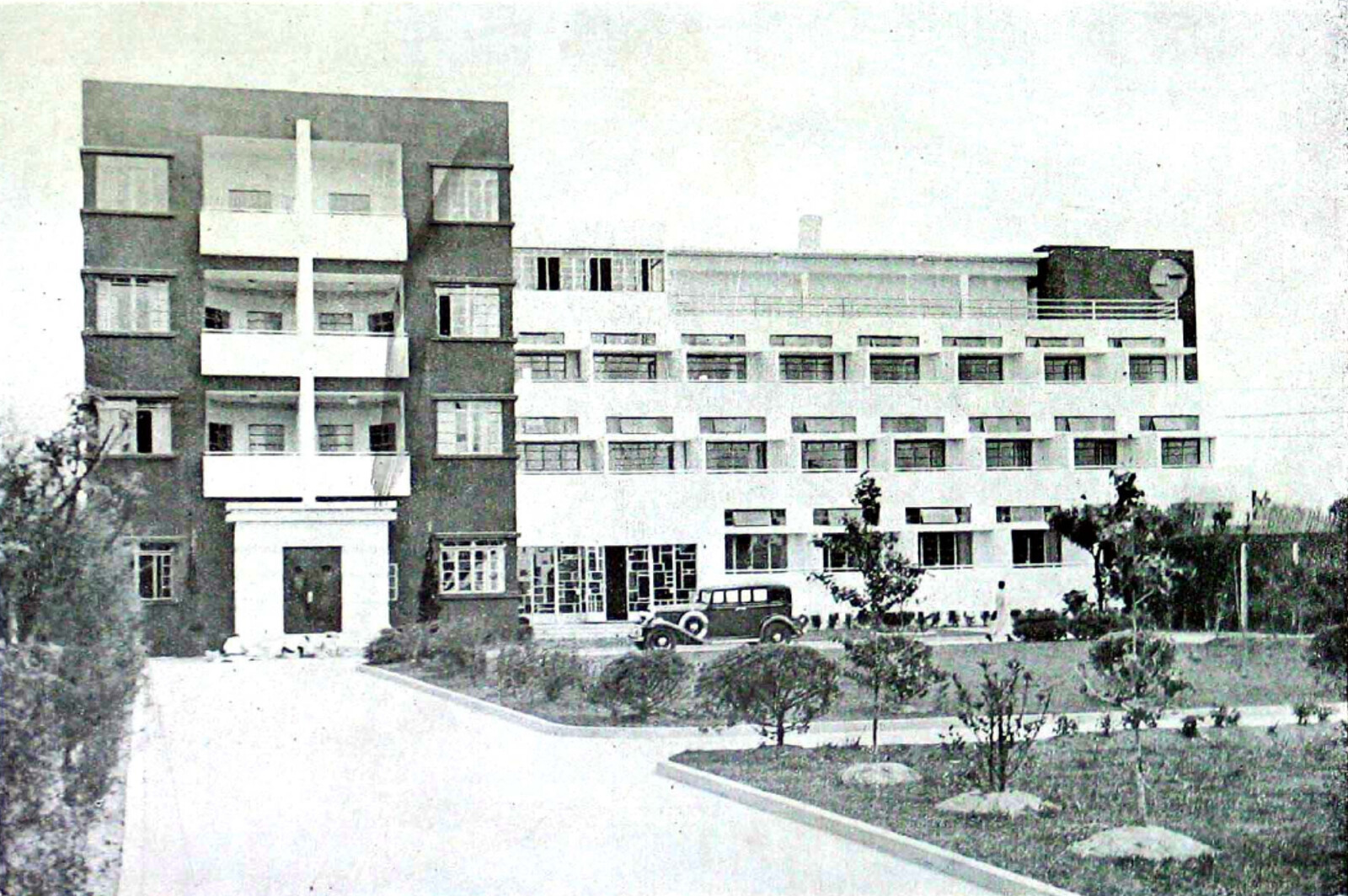

Front façade of the Ellis Island Immigration Station after completion in 1900. Photograph by Edwin Levick, 1902–1913. New York Public Library.

Although the national border had to deal with many underlying racial, colonial and socio-economic conditions, and cannot be reduced to an immigration checkpoint, Ellis Island exposes how architecture facilitated the checking and selection of new American citizens. As a result, the Ellis Island Immigration Station became a place where “examination for disease” was used as a way to screen undesirable from desirable bodies and to project this imagination to the public as an idea of a proper citizen. Architecture not only provided the material space for segregation and classification during the medical screening of immigrants. By exposing the process of medical examination to a wider public, it also served as an amphitheater for broadcasting a particular ideology of immigration.

Today, Ellis Island functions as a Museum of Immigration, where the voyeuristic practices of the early 1900s visitors continue in a new context and in a contemporary, romanticized vocabulary. Meanwhile, the contemporary border regimes of exclusion have moved elsewhere, but remain, in most instances, facilitated by architectural and dehumanizing processes of segregation.

Harlan D. Unrau, Ellis Island, Statue of Liberty National Monument, New York-New Jersey (Denver: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984), XIX.

“New Immigrant Station,” New York Times, December 3, 1900.

For instance, in 1912, The Popular Science Monthly published an article titled “The Medical side of Immigration.” The article, written on pseudo-medical evidence, describes how some immigrant races are more desirable than others from a medical point of view, taking as example some of the immigrants arriving to Ellis Island: “According to the law, the feeble-minded, as well as idiots and imbeciles, are absolutely excluded. It is of vast import that the feeble-minded be detected, not alone because they are predisposed to become public charges, but because they and their offspring contribute so largely to the criminal element.” (389) It continues, “In general, it may be said that the best class is drawn from northern and western Europe and the poorest from the Mediterranean countries and western Asia. Among the worst are the Greeks, South Italians, and the Syrians, who emigrate in large numbers. The Greeks offer a sad contrast to their ancient progenitors, as poor physical development is the rule among those who reach Ellis Island, and they have above their share of other defects.” (390) On European immigration into the US and whiteness, see: David R. Roediger, “New Immigrants, Race, and ‘Ethnicity’ in the Long Early Twentieth Century,” in Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs (New York: Basic Books, 2018).

On Ellis Island and the industrialized inspection process, see: Jay Dolmage, “Ellis Island and the Inventions of Race and Disability,” in Disabled upon Arrival: Eugenics, Immigration, and the Construction of Race and Disability (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2018), 14.

Unrau, Ellis Island, 3.

Ibid., 35.

On the American peak of immigration, see: Alan M. Kraut, Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the “Immigrant Menace” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 4.

“New Immigrant Station.”

“New Immigrant Station” elaborates: “The plans and specifications for the new structure were selected from the designs submitted by the architectural firm of Boring & Tilton of this city…The style is a conglomeration of several styles of architecture, the predominating style being that of the French Renaissance. The material used in the construction is brick, with light stone trimmings, harmonized so as to make the general effect as attractive in appearance as possible…But the interior arrangements are what, after all, make the station a model of completeness. Every detail of the exacting and confusing service to which its uses are to be dedicated were considered in perfecting the interior plans. The transportation, examining, medical, inquiry, and various other departments of the service being assigned quarters that, while they are practically separate in every detail, yet are so arranged as to follow one after the other, according to its proper place in the department…Every inch of space on this floor is utilized. The railings forming the network of the aisles, in which the immigrants are placed in alphabetical order, according to nationality, gives the great amphitheatre the appearance of an immense spider web…Surrounding this room, from the third floor, is the observation gallery, where visitors can watch the Inspectors at work…One of the greatest of the improvements will be the. bathing house, where 200 immigrants can be bathed at a time, 8,000 being about the number that can be thus refreshed during an ordinary day. ‘We expect to wash them once a day, and they will land on American soil clean, if nothing more,’’ said Assistant Commissioner McSweeney a few days ago…The floors are of concrete and slate, the railings. of iron, while the beds are combinations of iron and wire netting…The spending of the million and a half dollars by the Government on Ellis Island will be, according to those best fitted to judge, the beginning of a new era in the complicated system of the immigration service.”

On first-class tickets, and immigrant regulation, see: Unrau, Ellis Island, 226. Specifically: “Notice Concerning Sale of First Class Transportation to Immigrants at Ellis Island,” November 24, 1911, William Williams, Commissioner, Taft Papers, Library of Congress.

Already, the architecture of the Island facilitated the medical examinations (indeed, in 1911, the Unites States Health Service published a diagram for the trachoma checks, that literally translated them into a floorplan). The Trachoma protocol outside the Immigration Building at Ellis Island was introduced in 1911, after some structural reforms in the building. Previously this check was performed indoors, at the Great Hall.

Howard Markel, When Germs Travel: Six Major Epidemics That Have Invaded America and the Fears They Have Unleashed (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 83.

Interestingly, there is a clear circulation connection in plan (see images) between the holding medical examination rooms, the detection center, and the exit to the quarantine and infectious disease hospital on the other side of the Island.

Kraut, Silent Travelers.

On the origin-related differences in inspection procedures at Ellis Island, see: Alison Bateman-House, “Medical Examination of Immigrants at Ellis Island,” AMA Journal of Ethics 10, no. 4 (April 1, 2008): 235–41.

Markel, When Germs Travel, 83.

David Roediger has written how these populations were perceived as separate ethnic groups not belonging to the “white America”, and were later whitened in the United States. See Roediger, “New Immigrants, Race, and ‘Ethnicity,’” in Working Toward Whiteness.

See: Lorie Conway, Forgotten Ellis Island: The Extraordinary Story of America’s Immigrant Hospital (New York: Smithsonian Books /Collins, 2007); The United States Public Health Service, Book of Instructions for the Medical Inspection of Immigrants (G.P.O., 1903).

This preliminary inspection, from what can be deducted from the photographs, was performed at the same time and in the same space for both men and women, segregated in groups by nationalities. However, those with calk-marks were detained in holding areas and separated by the suspected medical affection and by gender.

Conway, Forgotten Ellis Island, 34.

As Allan M. Kraut describes, in many cases, the payment of the hospitalization was covered by immigrants’ societies based on nationalities or ethnic groups. Kraut, Silent Travelers, 56.

Within the eugenics rhetoric, the categories of race and physical and mental disabilities were created in service of racism. See Dolmage, “Ellis Island,” Disabled upon Arrival, 23.

During the first half of the 20th century, there are several archives examples of deportation at Ellis Island of Immigrants qualified by the Medical Inspectors at Ellis Island as “Likely to become a public charge.” One archived document report shows the interview and findings for the status of Giuseppe Giorni, a 27-year old male immigrant from Italy. The inquiry determined Giorni was to be deported because of his varicose veins which would lead to him likely becoming a public charge. See: “Report of a Special Inquiry Held at Ellis Island Regarding the Deportation of Italian Immigrants, 6/5/1915,” European War—German Refugees—Deportation of Italians—Alien Deportations, Subject and Policy Files 1906–1957, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service 1787–2004, National Archives, Washington, D.C. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/12013855

The topics of the eugenics nation and the design implications exceed the scope of this essay, but open an exciting research possibility, already developed in: Alexandra Minna Stern, Eugenic Nation : Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005); Howard Markel and Alexandra Minna Stern, “Which Face? Whose Nation?: Immigration, Public Health, and the Construction of Disease at America’s Ports and Borders, 1891–1928,” American Behavioral Scientist 42, no. 9 (June 1, 1999): 1314–31.

Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended: Lecture Series at the Collège de France, 1975–76, eds. Mauro Bertani and Alessandro Fontana, trans. David Macey (New York: Picador, 2003).

Foucault, Society Must Be Defended, 61.

Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” trans. Libby Meintjes, Public Culture 15, no. 1 (2003): 11–40.

See Michel Foucault, “Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College de France, 1977–78,” Choice Reviews Online 45, no. 4 (December 1, 2007): 45–1971.

US Public Health Service, Book of Instructions.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.