Eyes set on a village in the distance, a man stands in the midst of a peaceful landscape. Two crutches support his posture. His hands rest firmly on the wooden bars. His right foot is set on the ground. The man misses his left lower leg. Crutches counteract this absence. This image by Dutch painter Louis Raemeker appears in British landscape architect Thomas Mawson’s book An Imperial Obligation: Industrial Villages for Partially Disabled Soldiers & Sailors. Dedicated to his son Private James Radcliffe Mawson, who died in the battle of Ypres in August 1917, An Imperial Obligation proposed to create special surroundings for “the partially disabled soldier; for the new and strange conditions under which he must, from the nature of his infirmity, live and work in the future.”1 New surroundings would give the man, according to Mawson, “with eyes more troubled than when he looked over the stricken fields of France,” a new perspective on his future.2 The adapted built environment could restore “peace of mind where we are unable to rebuild the shattered body.” Normality was a structuring force in Mawson’s writings. It was central to the village’s design. For those whose bodies and lives were irreversibly transfigured by war, the village aimed for nothing more than a “normal” environment.

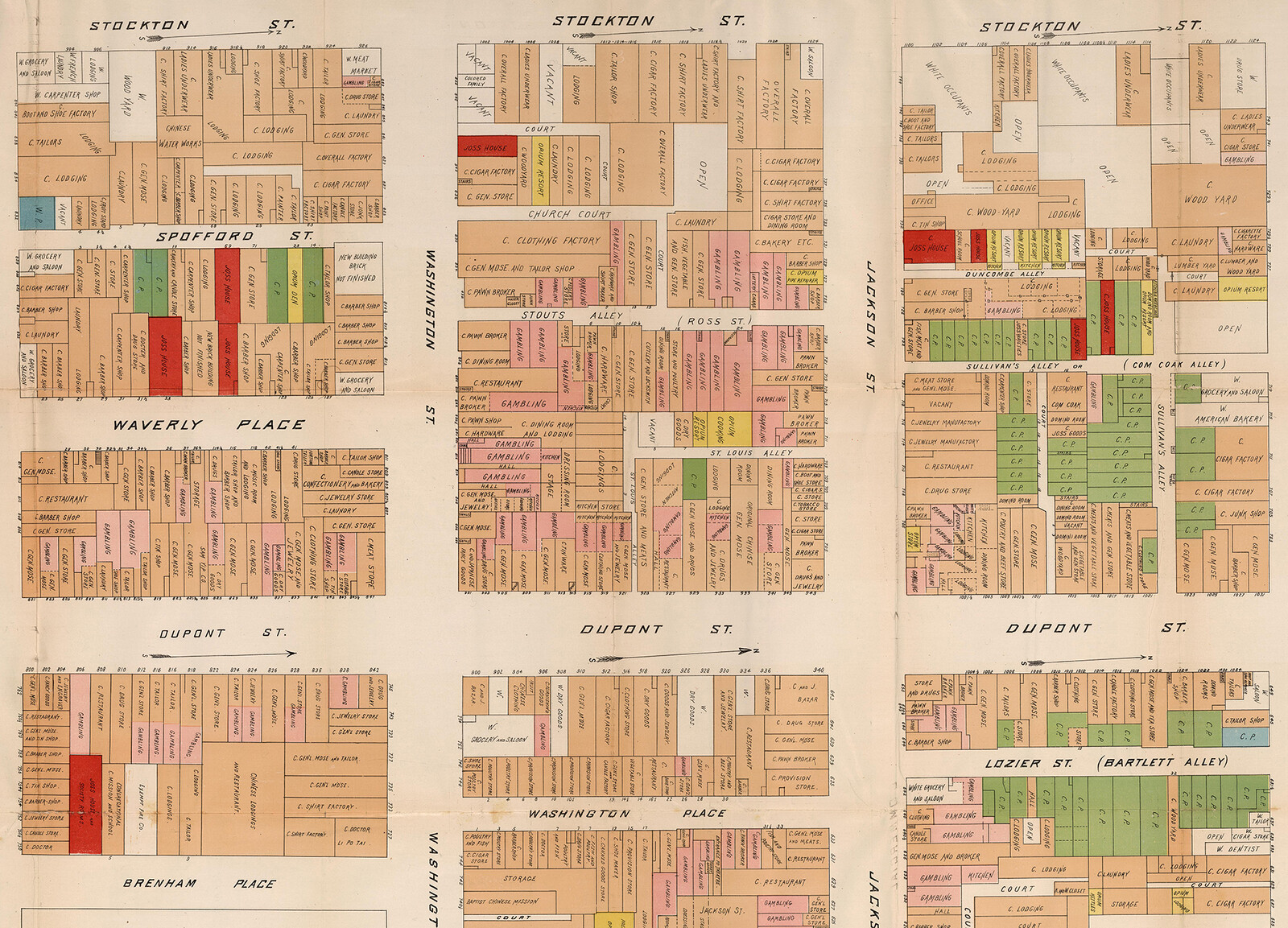

The physical legacies of World War I had a dramatic impact on the collective European psyche and landscape. They also affected its cities and architecture greatly. The Great War left “more than 750,000 ex-servicemen permanently disabled” in Britain alone, and specialized institutions arose to accommodate them.3 If, as historian Annette Becker concludes, the Great War was “a laboratory for the twentieth century: a field experiment or test site where violence could be carried out,” this war laboratory also produced architectural experiments when the battle was supposedly over.4 Architecture was enlisted in Britain’s post-war reconstruction effort. Mawson’s plans became part of this collective endeavor. One year after the publication of Imperial Obligation, the residents of Lancashire county acknowledged their “obligation” (as the architect termed it) and undertook the creation of two memorials: one conceived to be a commemorative stone monument, and the other an entire village.

The official unveiling of the Westfield War Memorial, 1924. Photo courtesy of Westfield Memorial Village.

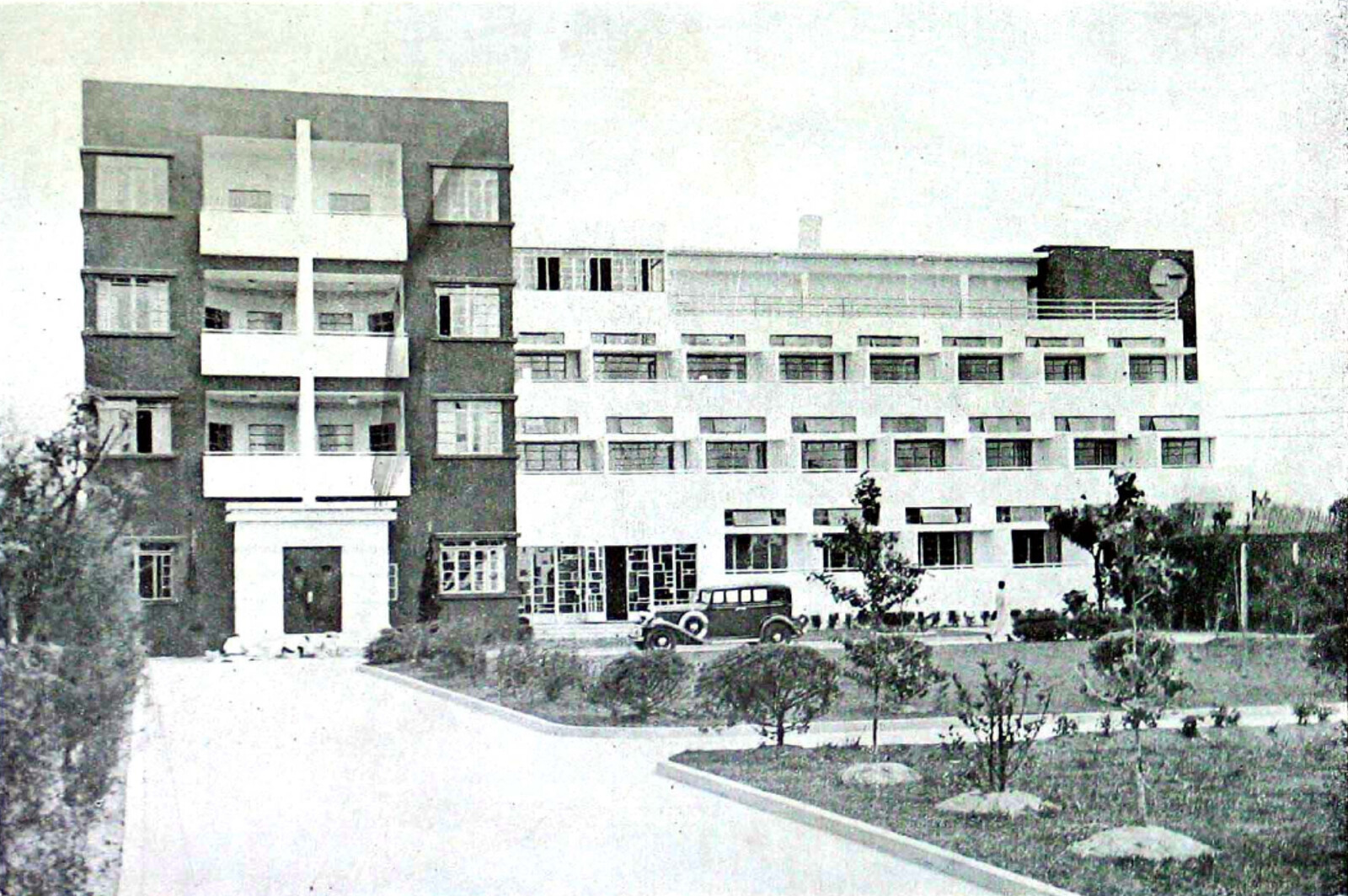

Westfield Memorial Village was to accommodate disabled war veterans and recognize their service in battle. Designed by Mawson and supported by local industrialist Herbert Lushington Storey, the foundation stone of the village was unveiled in 1919.5 By then Mawson’s project had acclaimed wide fame. In 1918, politician Sir Alfred Hopkinson praised philanthropist Storey’s action and called “the development of industrial villages … one of the most hopeful things to look forward to in the rebuilding of Britain.”6 American journals equally lauded Mawson’s sketches.7 The project also elicited critical reactions. In the Interallied Conference on the Aftercare of Disabled Men of 1918, Mawson recalled views that found his scheme “impractical and uneconomical.”8 The Director of the Red Cross Institute for Crippled and Disabled Men in New York, Douglas McMurtrie, criticized that these villages would nourish “a segregation of the disabled.”9

Westfield was founded at a time when, as Stefanos Geroulanos and Todd Meyers point out, new kinds of injuries reshaped the thinking of soldiers, doctors, theorists, and policy makers alike, leading to “the rise of a new conceptual architecture that offered a new epistemology of the body, a new ontology, notably of patienthood.”10 This “puzzle of wounds” left its imprint not only on concepts held by actors from the medical and political community, but also architecture.11 Five years after discussions on Mawson’s designs saw print between 1918 and 1919 in the European and American press, the first veterans—primarily men that had served with the city’s local regiment (the King’s Own Royal Lancasters) and Lancastrians who had been left with a lasting disability—arrived at the twenty-six completed cottages.

The village’s architecture was based on Mawson’s original sketches. Components of the original plan that were part of Imperial Obligation became central aspects of the built environment in Lancashire. The presence of banks, shops, a cinema, schools, churches, hotels, libraries, and a post office recalls the structure of a “normal” village. A factory, warehouses, and workshops remind of the village’s industrial character. Extensive space left for gardens, fields, greens, and orderly cottages concretize Mawson’s aim of maintaining a rural character for the soldiers’ village. These individual components—the cottages, the factory, the gardens—contribute to our understanding of the post-war reconstruction processes.

The memorial monument at the village’s center raises questions on the adapted nature of Mawson’s village and the normalizing (re)construction processes that reacted to the lasting imprint of World War One. Storey, the project’s main donor, commissioned the local sculptor Jennie Delahunt to create a model that represented a soldier handing water to his wounded comrade. “[Gracing] the small formal garden with its bright-hued flowers occupying the middle of the Town Square,” the sculpture was placed on top of two platform-like steps and a plinth.12 To those for whom Westfield was built, Delahunt’s sculpture was only meant to be looked at from a distance; a constant “reminder to passers-by of those who have gone west during these fateful years.”13 Westfield’s cottage structure, the garden’s emplacement, as well as the conception of the factory only furthered this distance.

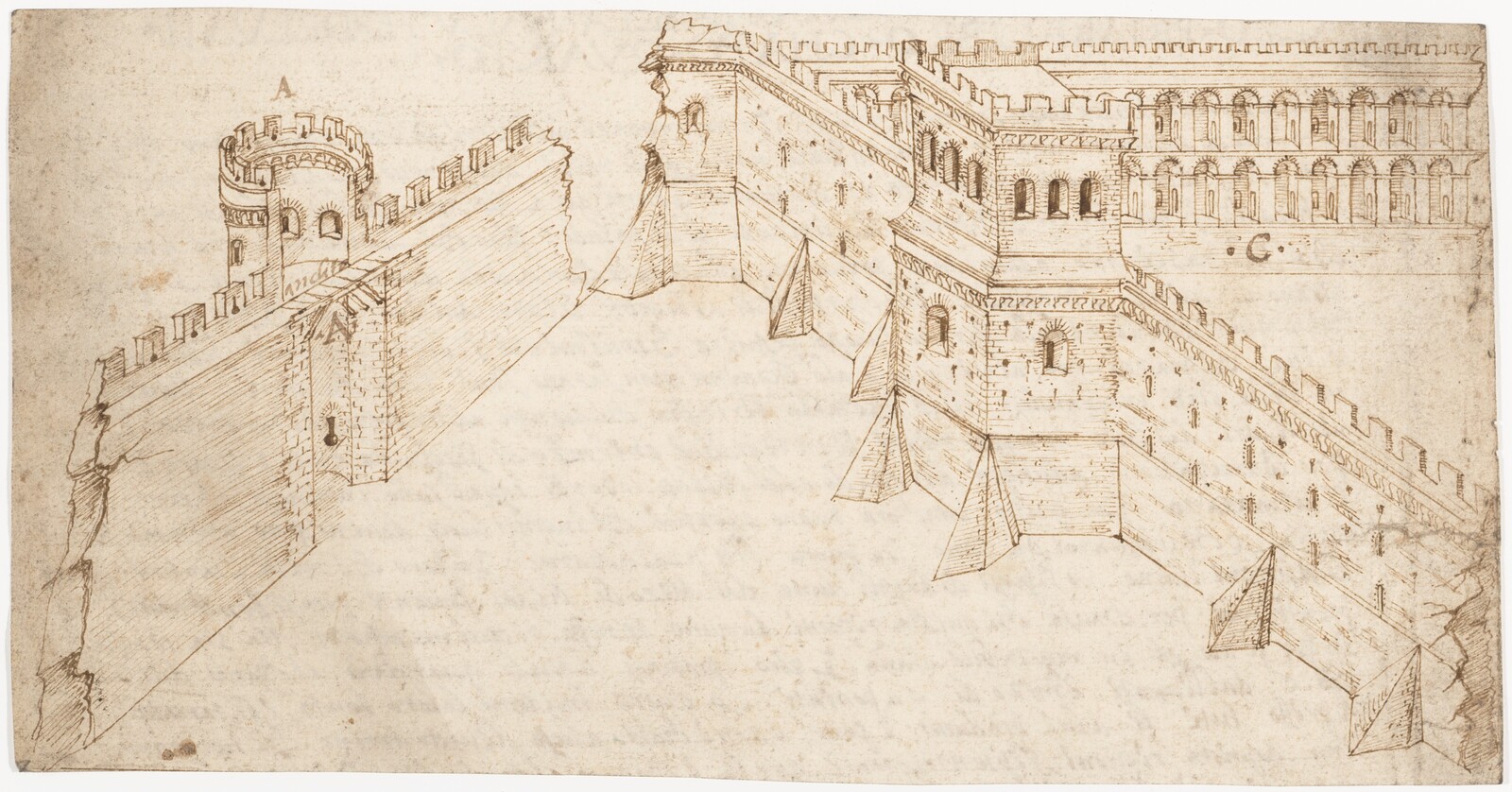

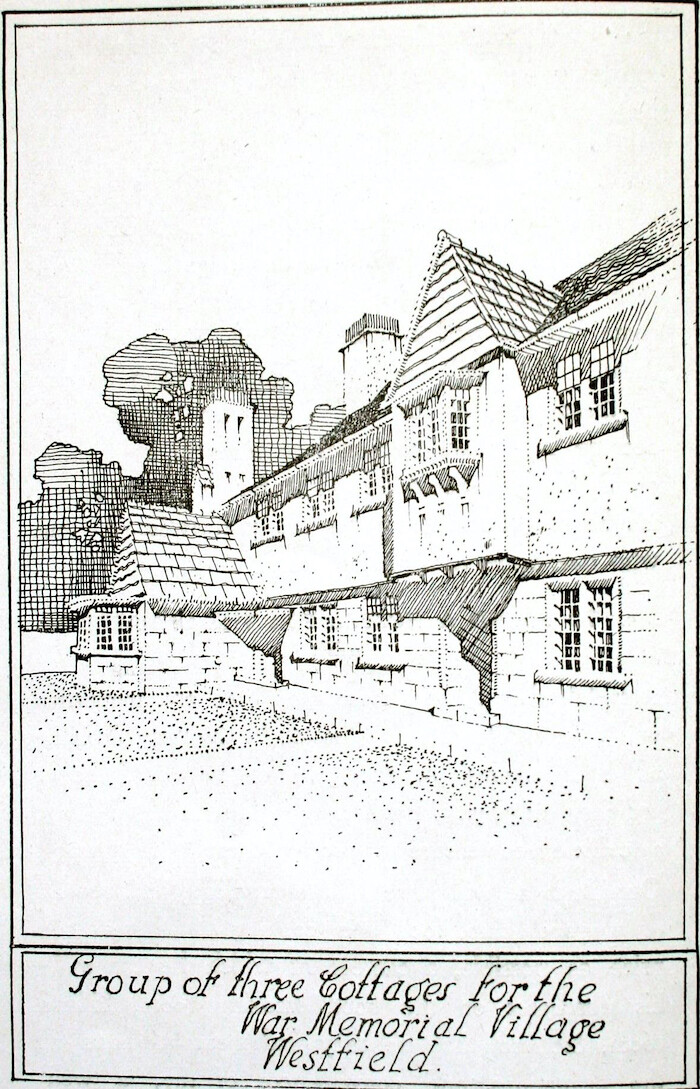

Perspective drawing of cottages planned for Westfield by Thomas Mawson, included in the first Westfield promotional booklet, published in 1919. Source: Martin Purdy, “Westfield War Memorial Village: Disability, Paternalism and Philanthropy, 1915–2015” (PhD diss., University of Lancaster, 2017).

The Cottages

Mawson considered “self-contained cottages” to be key in creating a sense of normality.14 “Our dream is to consist of a village and not a barracks,” Mawson wrote.15 As “the majority of the initial intake of Westfield tenants were men who lost lower limbs,” Mawson sketched out “broadened doorways, aisles, and gangways for the accommodation of bath-chairs and wheeled litters.”16 Many of these “normalizing” measures, however, were not implemented upon construction. Twenty-two of the original twenty-six houses were built as two-story cottages, presenting an obstacle to anyone with a movement impairment condition.17

This idea of “normality” not only influenced the design of the cottages, but also impacted the criteria for who could ultimately live there. The “26 families made up of 72 adults and 51 children” who would be given a house needed to be disabled by the war, have a local background, be married, and generally clean and respectable.18 Some of the first tenants included Mr. T. Cragg, “a father of two, whose left leg had been amputated, Mr. J. Rumley, another father of two who had a 100 per cent disablement (paralysis) as the result of several ‘severe’ wounds, and Mr. C. Howse, a father of five with a severe leg injury.”19

Photograph of war veteran Herbert Billington, “who had lost an arm and a leg to a German shell, lived in the front parlor of a two-story house as there were not enough bungalows.” Photo courtesy of Billigton family. Source: Purdy, “Westfield War Memorial Village,” 2017.

The disabled veterans, often fathers, lived with their unwounded families in these cottages. As Mawson’s plan illustrates, a “working-man’s hotel” was further installed near the recreation ground to house relatives.20 While interactions between disabled ex-soldiers and unwounded residents were part of life in Westfield, the landscape architect located the village’s success particularly in creating a context that allowed the veterans to share experiences of disability with each other. Arguing against criticisms of a possible segregation, “of herding together” the disabled, Mawson insisted on the village’s communal character.

He found that the “crippled hero” was “most painfully reminded of his disablement when “surrounded by and competing with the able-bodied and struggling all the time in competition with them.”21 As Westfield offered a space for both veterans and unwounded residents, Mawson emphasized the possibility of creating an environment that enabled a collective experience of disability. Westfield thus created a framework that familiarized its unwounded residents with problems that arose through wounds carried away from the fighting of World War I. The surprising cottage structure that privileged multi-storied houses, makes us wonder, however, to what extent disability stood at the center of this environment.

The Factory

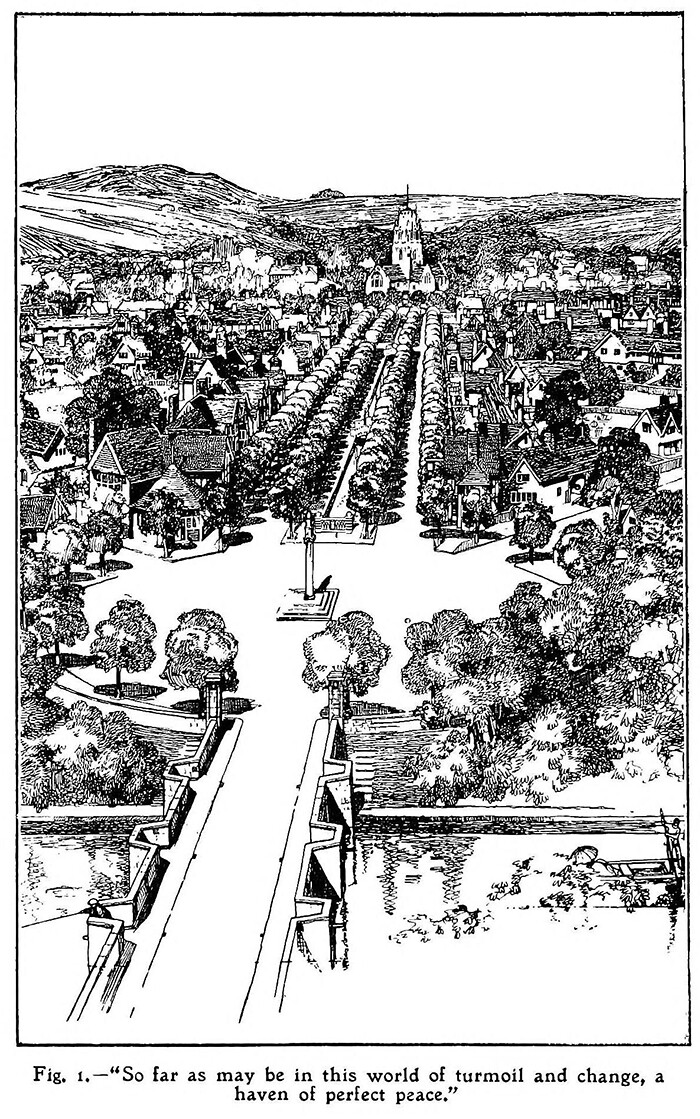

Conceived to nourish a shared experience of disability and interactions with unwounded residents, Westfield Memorial Village was designed to “chase away … the veil which shrouds a future overcast by the burden of a lifelong physical disability.”22 Mawson’s “real villages” were to lead to a new future, one “grow[ing] from their own root, in which the children of [the] protégés would grow up and take place in factory, office, shop, or husbandry.” Towards these ends, Mawson’s plan for Westfield included “elementary and high schools,” as well as a factory.23 Mawson was interested in recovering the disabled body’s productivity, and evoked the idea of the worker as “a machine capable of infinite productivity” common to late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century discourses around energy.24 Mawson argued that the post-war country could not afford to let “all the energy remaining to the partially disabled run to waste or be used inefficiently.”25 He considered “the creation of an exceptionally favorable environment” essential to the efficient use of this energy, thereby preserving “a spirit of sterling independence and self-helpfulness.”26

This idea of energy efficiency ran from Mawson’s treatment of the individual body to the environment he positioned it in. As early as 1901, Mawson argued for the need to group buildings “economically and practically to ensure the smallest amount of unremunerative labor and running to and fro.”27 In Westfield, units were “part of a larger composition embracing everything within sight,” all surrounding a square, “the administrative center of the village, that holds banks, the post office, largest shops, a cinematograph theatre, and the offices of the committee.”28 Only one “electric generating station supplies the village with light for public and private uses and power for its various industries.”29 Mawson placed industries “in relation to railway facilities” to speed the arrival of raw materials and the dispatch of finished products.30

Centralization, in this sense, would increase efficiency and ensure rentability, and further allow for “the arrangement of special conditions of work to meet special needs.”31 Spaces that were adaptable to veterans’ individual skills would further encourage efficiency and self-sufficiency. Mawson warned that “every man must be seen following the occupation he is best fitted for mentally, temperamentally, and physically.”32 This reflected the wider views of The Disabled Soldier’s Handbook, published by the Ministry of Pensions in 1918, which claimed that “the first thing to do” as a disabled veteran “is to get as well and to keep as well as you can. The next thing is to get back to work of a kind that you can stick to.”33

Factory workers, craftsmen, writers, composers, agriculturists, and shopkeepers all interacted at Westfield. Alongside the main avenue, Mawson designed buildings “containing shops on the ground floor with flats behind and over,” with workshops placed on the top floor. Goods produced on the upper floors could thus be “sold or dealt on the ground floor.” An elevator was also provided within these buildings, “for the easier conveyance of materials and articles of trade, but also for the use by those employees too crippled for the safe or easy climbing of stairs.”34

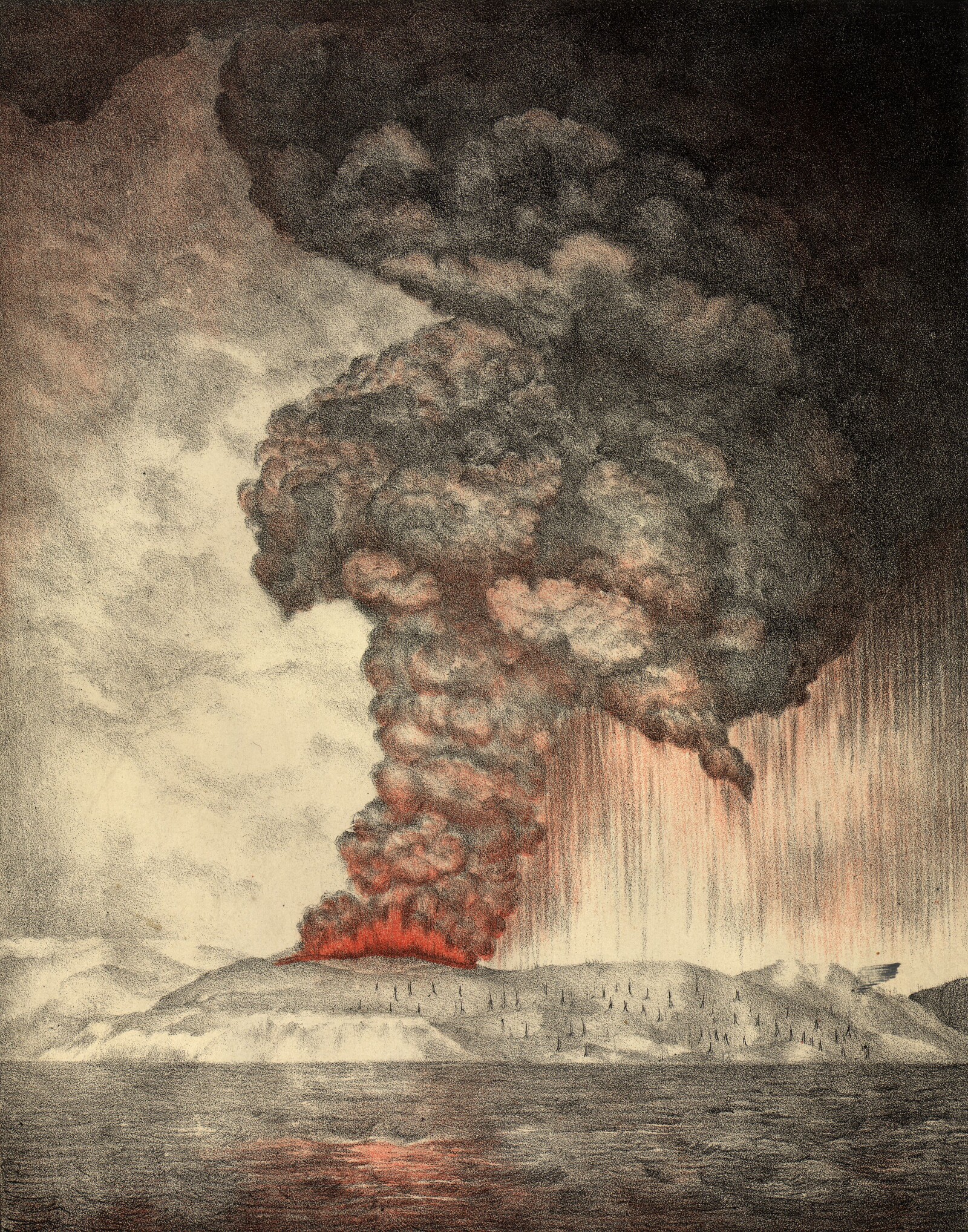

“So far as may be in this world of turmoil and change a haven of perfect peace,” 1917. Drawing from Mawson, An Imperial Obligation, 2.

The Gardens

As Mawson’s original plan illustrates, alongside workshops and warehouses, much space was left to gardens. “It is among God’s creations in His country that we place our crippled soldier,” Mawson wrote in An Imperial Obligation.35 Influenced by Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City concept and the Arts and Craft Movement, the soldiers’ village was to be a “product of English rural life.”36 His plans called for “more open-air life” through the installation of market gardens, bulb farms, agriculture, and animal husbandry at the outskirts of the village.37 Echoing Raymond Unwin’s and Richard Parker’s focus on the union of craft and intellectual work through cottage homes, the village was to be as “artistic as it is practical,” and bound together by “present activities and surroundings, all working together in happy collaboration.”38

Mawson considered gardens an essential element of creating a “normal” environment. Each property was meant to have a large garden. Westfield’s committee members, however, focused on their maintenance, and chose tenants according to their capacity to garden.39 Worries about the effects “on the wider aesthetic,” on “the community’s natural façade” even led to the introduction of a tenancy condition to keep one’s house and gardens “clean and tidy,” and those who failed were threatened with eviction. This echoed the conclusions of the 1918 National Conference on Housing after the War, which recommended that “when such garden land is provided, town planning schemes should include adequate power for the responsible authority to enforce upon the occupier its use for the purpose.”40

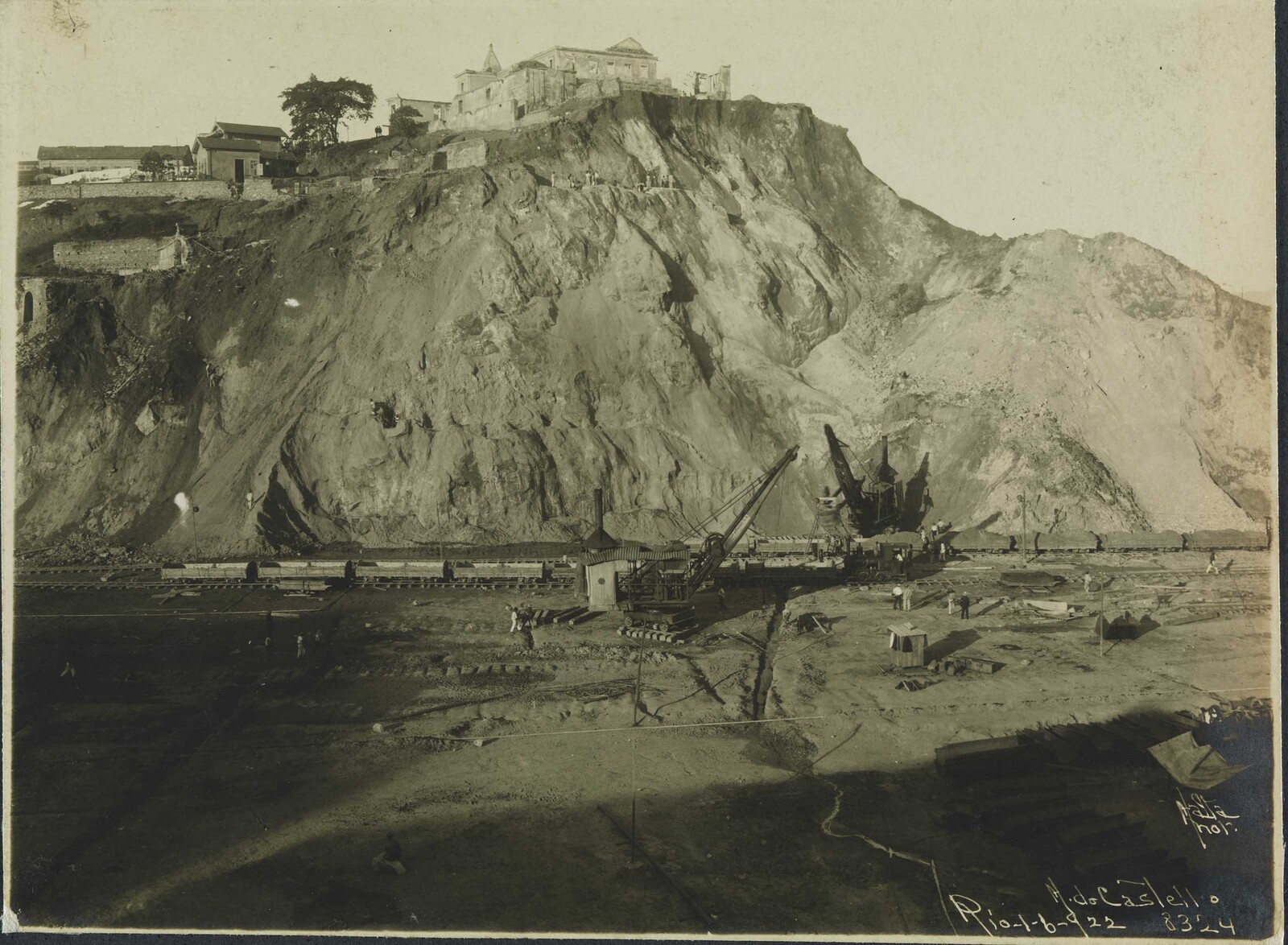

Westfield’s main driveway as seen in a promotional booklet for new World War II housing, 1943. Courtesy of War Memorial Village Lancaster. Source: Purdy, “Westfield War Memorial Village,” 2017.

The gardens of Mawson’s village enforced a neat appearance and were part of an architecture that, though conceived to respond to the disabled body, continued to evoke “normality.” The village’s Playing Field was designed “on simple and harmonious, but nevertheless dignified lines.”41 And the workshops, which were designed with “strongly marked horizontal lines, leading the eye forward to the more ordered architecture of important buildings surrounding the Town Square,” further contributed to the tidy appearance of Westfield.42 Even the village hospital “is facing pleasantly across the open field.”43 A general effect of one of these “vistas” turns around impressions of pleasantness, dignity, and harmony. The conception of the gardens and green spaces in Westfield place notions of harmony or pleasantness at the fore. A preoccupation with practicalities, such as the veterans’ ability to carry out garden work, was almost absent.

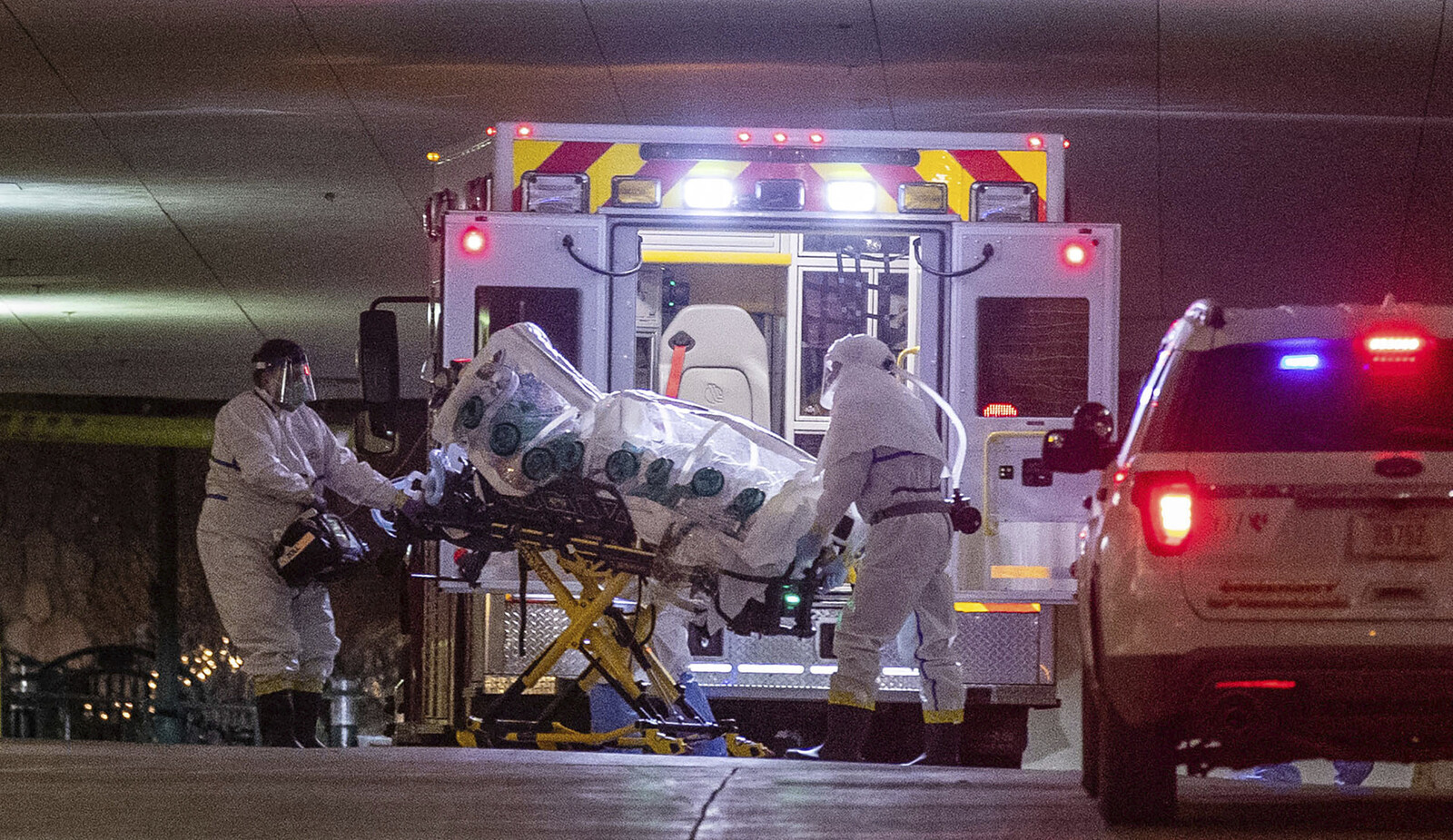

War Memorial, Westfield Village, Lancaster. Photo by Graham Hibbert, 1974.

Crutch or Prosthesis?

Looking at these individual components makes it seem as if Mawson sought to use architecture to break with the past of the Napoleonic wars. “Then,” he writes, “the maimed soldier was stumping the country from village to village … a sight too humiliating alike to our self-respect and our sense of fitness.”44 In the face of this memory, An Imperial Obligation forewarned those who might imagine themselves meeting “draggled, haggard, and miserable objects, painfully conscious and even ashamed of a disablement which cannot be hid,” upon entering the memorial village. 45 Westfield was “a real village … far from a village of cripples, as we will be able to clothe it with a general air of well-being and industrious contentment.”46 Architecture was conceived to clothe at Westfield. The village helped to shroud and veil the war veteran’s disability.

Lennard Davis argues that “we live in a world of norms.”47 This world structured the cottages, the central space, the ordered gardens of Lancaster’s memorial village. The seemingly neat, stable lines of its architecture break apart, however, when one ceases to perceive the disabled war veteran as a given entity. Behind the veil of neat gardens and orderly cottages stand dismembered bodies, bodies taken apart by designers and the committee’s selection process, bodies reconstituted to a wholeness in a “pleasant” rurality, re-membered in a memorial space.48 As disability shaped Westfield’s architecture, the built environment shaped the disabled body. Lines between the veterans’ torn war body and design were blurred. The environment became prosthetic, but it is ultimately unclear who wore Westfield.

Thomas Mawson, An Imperial Obligation: Industrial Villages for Partially Disabled Soldiers, (London: Grant Richards Limited, 1917).

Ibid., 5.

For overviews of these institutions, see: Deborah Cohen, The War Come Home: Disabled Veterans in Britain and Germany, 1914–1939, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 2; Julie Anderson, War, Disability and Rehabilitation in Britain: “The Soul of a Nation” (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011).

Annette Becker, “The Great War: World War, Total War,” International Review of the Red Cross 97, no. 900 (2015): 1029–1045, 1032.

Martin Purdy’s doctoral thesis on Westfield has nurtured this paper through his discussions of archival sources. See Martin Purdy, “Westfield War Memorial Village: Disability, Paternalism and Philanthropy, 1915–2015” (PhD diss., University of Lancaster, 2017), 14.

Alfred Hopkinson, Rebuilding Britain: A Survey of Problems of Reconstruction After the World War (London: Cassell, 1918), 145.

A book review of the American Architect and Architecture found “Mr. Mawson’s dream well worth our serious conservation ‘over here,’” while an editorial in Landscape Architecture, the magazine of the American Society of Landscape Architects, considered it “fortunate that Mr. Mawson’s plans will be given an opportunity to prove their practicability.” See: T. K., “Industrial Villages for Disabled Soldiers,” Landscape Architecture 9, no. 1 (1918): 32–34. Mawson’s project also appears in Theodora Kimball, “Our British Allies and Reconstruction,” Landscape Architecture 8, no. 4 (1918): 169–174. An Imperial Obligation further made its way into a range of American libraries and organizations, such as the National Housing Association, the Department of Labor, and the U.S. Army War College. It continued to be filed in bibliographies under section titles, such as “Refitting Men into Normal Family and Community Life.” See, for example, Strayer Paul Moore and Committee, Outline Studies on the Problems of the Reconstruction Period (New York: Association Press, 1918), 16.

Interallied Conference on the Aftercare of Disabled Men London, John Galsworthy, The Inter-allied conference on the Aftercare of Disabled Men. Second Annual Meeting held in London, May 20 to 25, 1918. Reports Presented to the Conference (London: H.M. Stationery Off., 1918), 83.

T. K., “Industrial Villages for Disabled Soldiers.”

Stefanos Geroulanos and Todd Meyers, The Human Body in the Age of Catastrophe: Brittleness, Integration, Science, and the Great War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 318.

Ibid., 34.

Mawson, An Imperial Obligation, 43.

Lancaster Corporation, Minutes of the Members of the Council in Committee, February 12, 1919, 181, as quoted in Purdy, “Westfield War Memorial Village,” 137.

Mawson, An Imperial Obligation, 19.

Ibid., 8.

See Purdy, “Westfield War Memorial Village,” 103; Mawson, An Imperial Obligation, 103.

Purdy, “Westfield War Memorial Village,” 105.

See: “The Early Years,” Westfield Memorial Village, 2020, ➝; Purdy, “Westfield War Memorial Village,” 164.

Ibid., 98.

Mawson, An Imperial Obligation, 46.

Ibid., 83.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 89, 43.

Anson Rabinbach, The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity (New York: Basic Books, 1990), 2.

Mawson, An Imperial Obligation, 89.

Ibid., xxi, 49.

Thomas Mawson, The Art & Craft of Garden Making, (New York: Charles Scribner’s & Sons, 1926), 29.

Mawson, An Imperial Obligation, 38.

Ibid., 46.

Ibid., 36.

Ibid., 102.

Ibid., 8.

Ministry of Pensions, The Disabled Soldier’s Handbook (Marlborough: Adam Matthew, 1918), 3.

Ibid., 37.

Mawson, An Imperial Obligation, 6.

Mawson cites the promoters of the Garden City and Garden Suburb schemes once. See Mawson, An Imperial Obligation, 25, 47, 49.

Ibid., 46.

Ibid., 11.

Purdy, “Westfield War Memorial Village,” 117.

The National Conference on Housing after the War, Report of the Organizing Committee (Manchester: Kirkham and Pratt, 1918), 78.

Mawson, An Imperial Obligation, 44.

Ibid., 38.

Ibid., 44.

Ibid., 70.

Ibid., 81.

Ibid., 83.

Lennard Davis, The Disability Studies Reader (New York: Routledge, 2013), 1.

On the connection between dis- and re-membered bodies, see: Joanne Bourke, Dismembering the Male: Men’s Bodies, Britain and the Great War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 210.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.