My childhood playspace was in the basement of a condominium in suburban Connecticut. The room was allowed to be messy, disorganized, and filled with loud noises. This bounded tolerance for chaos came from my mom’s need, as a stereotypical Virgo (perfectionist), to keep childish clutter out of sight. Once I outgrew Barbie and stopped leaving her dream home, car, and clothing accessories all over the floor, the basement was converted into a man cave for my mom’s fiancé and his La-Z-Boy, hammer, pint glass, and football jersey. Both the playroom and man cave are spaces for items associated with one’s identity that don’t belong in the rest of the house. Not just childhood imagination but also exaggerated masculinity—a social product itself wrapped in displays of aggression, competition, and leisure—must be enclosed in a space hidden from the gaze of the domestic sphere.

Over the years, I began to realize that my distaste for suburban homes was related to my identity as a white, queer, and cisgender woman. Suburban and white traditional heteronormative gender roles work together to enforce “proper” binary expression and labor tasks scripted by the patriarchal American society.1 As a queer bachelorette, I was eager to leave for the city in search of a lesbianic version of Playboy’s Bachelor Pad. Simultaneously, the heterosexual family men that settle in the suburbs then protest their nuclear family structure by constructing aggrandized manly identities within its interiors surrounded by white picket fences, decorative window shutters, and perfectly groomed gardens.

My flee to the city and the space carved out by my mom’s fiancé share the same motivation—to evade the confines of the feminine. In the latter case, however, the family man seeks escape from within the limits of the domestic, that traditionally feminine space, by colonizing the forgotten, the transitional, the leftover spaces in a house like the garage, basement, or attic.2 Tied to the marriage script of the American dream, the family man instrumentalizes the suburban domestic as a form of domination even as it threatens his identity. Man caves cannot be understood outside of their relation to the totality of the adjacent interior spaces devoted to the construction of femininity.3

From Utilitarian Space to Masculine Sanctuary

Man caves frequently play key narrative roles in US sitcoms. Roseanne (1988–1997), for instance, portrayed a supposedly typical white working-class American family—husband and wife and three children—living in the suburbs of Illinois. The show was centered on Roseanne, the dry-humored matriarch, and plotlines featured parenting struggles as well as family members holding down various blue-collared jobs. When arguments broke out, Dan, the husband, would withdraw to the garage.

Married… with Children (1987–1997) depicts another suburban Chicago white middle-class family consisting of a husband, wife, and two kids. Most of the show’s humor revolves around the husband, Al, and his bad luck, unrewarding career as a shoe salesman, and constant annoyance towards his wife, Peggy. When she discovers she is pregnant with their third child in the sixth season (1991), Al wants only to escape.4 Trying to flee the responsibilities of the family man, he converts his garage into a second family room, complete with its own toilet, but for men only.

In the garage, both Dan and Al claim a territory segregated from the rest of the house as their retreat from family chaos. Dan’s space contains his “man chair,” a refrigerator stocked with beer, a dartboard (the classic bar game), and space to work on his motorcycle. Al’s space is set up more like a living room, with wood paneling and carpet, but shares certain elements with Dan’s room, including a seating area, TV, and a supply of beer. Al’s language is coarser than Dan’s, showing the extent that toxic masculinity can manifest inside these rooms of retreat:

Peggy Al, you’re not really thinking about moving away from me and the baby?

Al Thinking of it? I did it! Be gone, jackals!

Al pushes the family out of the man cave and secures the door with an excessive number of locks. He is soon visited by another husband, Jefferson, who expresses his disgust towards his wife, who is also pregnant.

Jefferson Having sex with your pregnant wife is like putting gas in the tank of a car you’ve already wrecked.5

In the movie The Watch (2012), a group of neighbors forms a local neighborhood watch group. The film’s premise is that this brotherhood of white men comes together to save the world from an outer space alien take-over, but the real reason for the group’s formation is that the members were looking for male camaraderie from their typical nuclear family structure. In particular, the character Bob, played by Vince Vaughn, invites the team over to show off his man cave. Bob’s man cave quickly becomes the main meeting space for the Neighborhood Watch and the site of shared rowdy masculine expression.

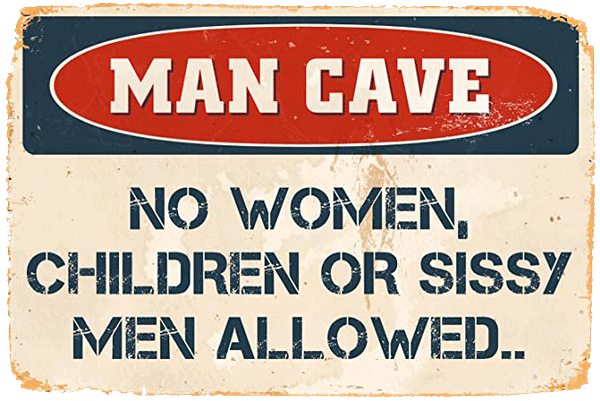

Source: amazon.com/StickerPirate.

Much like communities, the home is built around various experiences where each room represents different associations to family, marriage, and domestic labor.6 The homosocial life inside the man cave is a withdrawal from the feminized domestic space. Still, it is a domestic space in its own right with a kind of domesticity of men with it and constructed with ostensible feminine methods. The man cave mimics a house within a house, forming a counter-domesticity that impersonates all the required elements of a house with components of storing food and drinks, entertainment, sleeping, and sometimes even its own private toilet. The clubhouse or the community incubator is a kind of anti-feminine domesticity made with supposedly feminine methods.

The push for the suburban built environment moralized the family structure and, according to Margaret Marsh in American Quarterly, “discourages excessive attention to one’s individual wants.”7 Around the mid-1800s, middle-class domestic architecture produced homes designed for separation.8 But starting in the early 1900s, the suburban houses shifted their design to a less segregated division. Concepts of “family togetherness” were expressed through new notions of living rooms, and open floor plans began to replace spaces such as the parlor and what was idealized as the male refuge, the study.9

From Tim Allen’s Home Improvement and other sitcoms to DIY shows on HGTV, the portrayal of suburban white husbands and their man caves continues to spread across the televised spectrum as a model for inhabiting the suburban landscape. And today, online platforms and social media perpetuate the script of the traditional white middle-class family man seeking to claim a territory inside the home defined in opposition to feminine gender or labor roles.

Referred to as America’s first interior decorator, author Elsie de Wolfe observed in 1913 that “it is the personality of the mistress that the home expresses. Men are forever guests in our homes, no matter how much happiness they may find there.”10 And in 2016, when sociologist Tristan Bridges interviewed straight men about the meaning of their man cave in the context of their relationship, the most frequent response was, “I feel like the whole house is hers. And this is a space for me.”11 Bridges followed up by asking them which spaces in the house are “hers,” and in an echo of Betty Friedan’s 1963 The Feminine Mystique, the men would “list off rooms associated with domestic labor, not with leisure — the kitchen, the laundry room, the nursery, etc.” The garage, the attic, or the basement that are made into man caves are seen to not be owned by anyone.

The divide between public and private spheres was institutionalized in the twentieth century American landscape through an economic structure that privileged middle-class white families, which financially allowed for a one-person salary to support a household unit.12 This separation also gendered the built environment, contrasting the private domestic mother against the public working father, whose remaining domestic labor functions were relegated to extra-domestic spaces.13 The man cave demarcates a domestic space within the home, yet one where labor or care-work cannot be compelled. For men dwelling as husbands in the home—a space socially assigned to femininity—architecture and spatial arrangements work as exaggerated representations of identity. The man cave, then, is more than a retreat. It is both canvas and symptom of toxic masculinity.

The Museum of Macho Expression

The magazine Man Caves describes its namesake spaces as inviting fantasies “all dreamed up by guys and for guys,” and offers a “How To” guide to personalizing one’s man space through the collection of perfectly themed elements in that space. A specific personalized theme—the sports bar, the pub, rock’n’roll, the tool shop, the hunting shed, etc.—is key to achieving a theatrical impression of coherence among a curated selection of more or less standard essentials: recliners, TV/entertainment systems, bar and fridge, pool table, dartboard, poker table, sports memorabilia, pin-up posters, and bar stools/extra seating. Man caves often hint at sensations of violence and aggression that have been excluded from the masculine/feminine gender binary framework.

Walter Benjamin claims that the real potential of the interior space can only be attained through the identity of the collector:

The collector makes his concern the transfiguration of things. To him falls the Sisyphean task of divesting things of their commodity character by taking possession of them. But he bestows on them only connoisseur value, rather than use-value.14

Like the collector creating a fantasy of object culture, the creator of the man cave conceives a fantasy of masculine culture. Bridges connects the man cave to the lineage of the “bachelor pad,” a concept fashioned by Playboy in the 1960s to groom men into excessive consumers of goods and women by appealing to their teenage instincts.15 According to Paul B. Preciado, “the important thing about teenagers was not his age, but his ability to consume without moral restrictions… The young, white heterosexual teenager was the focus of a new cultural market structured around university life, jazz and rock and roll, movies, sports, cars, and girls…The teenager who was not yet tied down by marriage.”16 The man cave is, similarly, a macho archive of hyper-masculinity nostalgia that can only exist through the validation of other men.

In the interviews conducted by Bridges, most of the men revealed that they don’t actually have time for friends, and that their man caves are unfinished. When Bridges asked the men who they expected to use the space in the future, they did not have a clear response. In general, both the physical materiality and the social camaraderie of the man cave exists more in the realm of aspiration than in constructed reality. Jack Halberstam defines masculinity as the performative, social connection between maleness and power.17 With fantasy unable to become reality, then, the need to express one’s masculinity can spill over into the virtual spaces of forums, community boards, social media, and Zoom calls.18

In 2008, retired US Army intelligence officer Mike Yost founded The Official Man Cave Site LLC, ManCaveSite.org. Man cave dreamers who pay a yearly membership fee receive a certificate and hat, access to the online forums, and exclusive discounts on other Man Cave Site LLC merchandise. Forums serve as a platform for men to show off their man cave and look for validation as others seek ideas. The exchange of ideas and comments are curated in specific discussion groups from sports, cigars, and even “over-the-top” sandwich recipes. The site also gives out yearly awards for the best man cave in the United States and sports the tagline, “Taking back the world, one Man Cave at a time!”

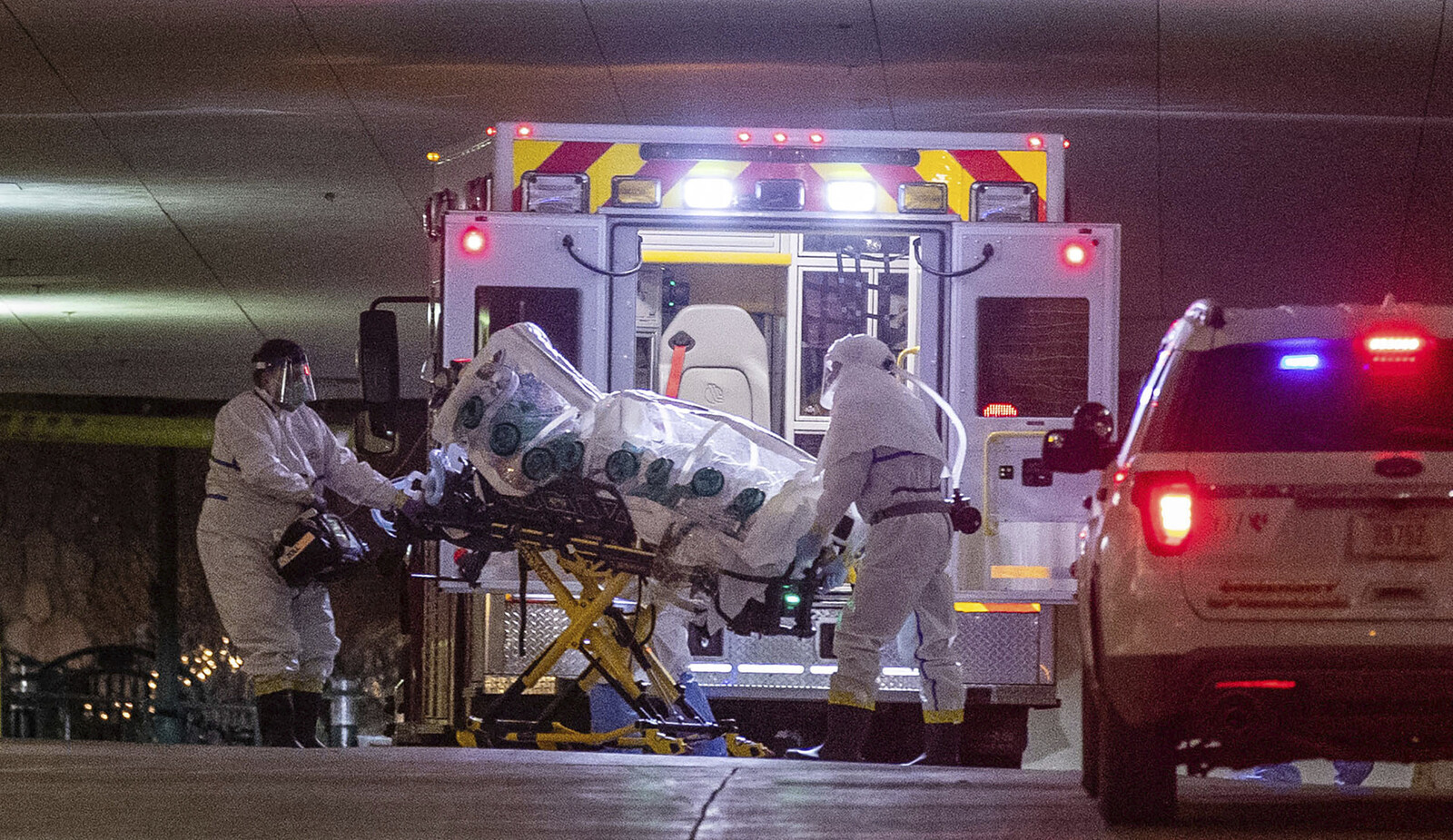

An Epidemic of Toxic Masculinity

The man cave is less as an inevitable consequence of suburban gender binaries than it is the designed outcome of the repeated choice to draw on this strict binary. After all, many converted basements, attics, and garages engage nuanced gender dynamics through different spatial typologies. The built environment cultivates community moments and becomes the stage for the cultural identity. But the hoarding of masculinity for social validation that takes place inside a man cave establishes a noxious codependency with the feminine domestic.

Whether the man cave is a physical or virtual expression, it stays in the gray space of fantasy between the binary of private and public realms. It lives in a scapegoat utopia that allows these family men to ignore work and a family’s daily responsibilities. Its purgatory location—a clubhouse within a house—asserts the belief that men dilute their toxic behaviors and manly alter-ego identities in the presence of women.

After the domestic’s material territorialization, with men staking a claim with hyper-masculine expression, the bounded physical environment forms a barricade against the panopticon of post-war family values. Here we see the synthesis of interiorized domesticity and the concept of shelter construction that creates “an almost literal attempt to control, reprivatize, render invisible, and bury not only domesticity but also women’s sexuality.”19 The man cave is a place where caustic dynamics become endemic to the relationship between gender identity, material culture, and architecture. Understanding the built environment as a mechanism for gender politics reveals a contemporary social epidemic of toxic masculinity.

According to Dolores Hayden in Redesigning The American Dream, homes in American still follow the Victorian script of the home outside the city as being defined as “woman’s place” and places within the city are labeled as a “man’s world.” See Dolores Hayden, Redesigning the American Dream: The Future of Housing, Work and Family Life (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002).

Interior Design and Identity, eds. Susie McKellar and Penny Sparke (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004).

Abby Ferber, “Keeping Sex in Bounds: Sexuality and the (De) Construction of Race and Gender,” in Gender, Sex, & Sexuality: An Anthology, eds. Abby Ferber, Kimberly Holcomb, and Tre Wentling (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 136–141.

The pregnancy is later revealed to be an invention from Al’s nightmare (due to the real-life miscarriage of the actress). See Andreas Carl, “Some Frequently Asked Questions,” Bundyology, May 31, 2009, ➝.

Married with Children, episode 6.0, “If Al Had a Hammer,” directed by Gerry Cohen, written by Kevin Curran, aired September 22, 1991, on FOX.

Toon Dreessen, “How Architecture Can Bring Communities Together,” HuffPost Contributor, May 8, 2015, ➝.

Margaret Marsh, “Suburban Men and Masculine Domesticity, 1870–1915,” American Quarterly 40, no. 2 (1988): 165–86.

See Gwendolyn Wright, Building the Dream (New York: Pantheon Books, 1981), 109–11; Gwendolyn Wright, Moralism and the Model Home (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 9–46.

Marsh, “Suburban Men and Masculine Domesticity.”

Elsie De Wolfe, The House in Good Taste (New York: The Century Co., 1913).

C. Brian Smith, “This Guy Studies Man Caves For a Living; Here’s What He’s Learned,” MEL Magazine, August 29, 2016, ➝.

Raia Prokhovnik, “Public and Private Citizenship: From Gender Invisibility to Feminist Inclusiveness,” Feminist Review 60, no. 1 (Autumn 1998): 84, 87.

Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard and Laura Heston, Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, 2017), ➝.

Walter Benjamin, “Paris, Capital of the 19th Century,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings 3: 1935–1938, eds. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2006), 39.

Kaitlyn Tiffany, “What Happened to the Man Cave?” Vox, March 4, 2019, ➝.

Paul B. Preciado, Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics (New York: Zone Books, 2014), 48.

Jack Halberstam, Female Masculinity (Raleigh: Duke University Press, 1998).

See the ManCaves website, ➝.

Preciado, Pornotopia, 74.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.