Survivance is dependent upon negotiating and being-with toxic relations as much as chosen and desired ones. Furthermore, discerning the toxicities from the nourishments within the very same relationship is a familiar task of anguish. This is the practice of being-with the kinships we do not choose—human and more-than-human. This is the practice of living inside of contradiction and contamination.

Book cover detail, Por Intharapalit, Chao Sao Phi Krasue (เจ้าสาวผีกระสือ; Krasue Bride) (Saeng Dao, 2002).

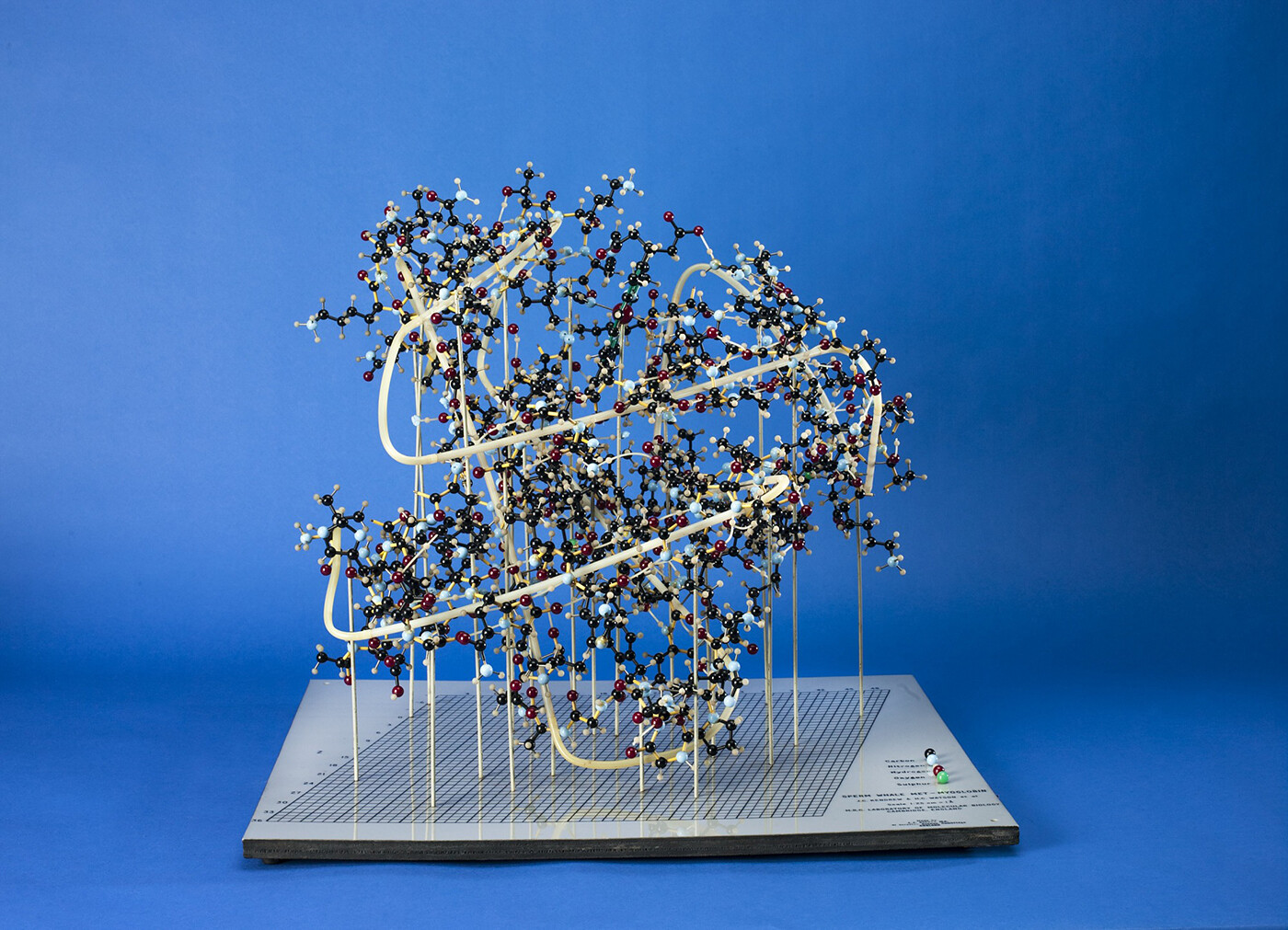

While scientists search the human genome for DNA sequences that set us apart from other species, evidence suggests that we share much of our genetic identity with viruses. Rhizomorphic connections with other creatures, mediated by our viruses, may be happening all the time, along thousands of lines of flight. Infectious agents link humanity with other creatures who live with us in shared multispecies worlds. We are kin with our viral relations.

There are a lot of unknowns in human interactions with viruses, especially when we are facing a newly emerging virus. But the idea of viruses as “things” provides an overall strategy that promises to leave us mainly with known unknowns.

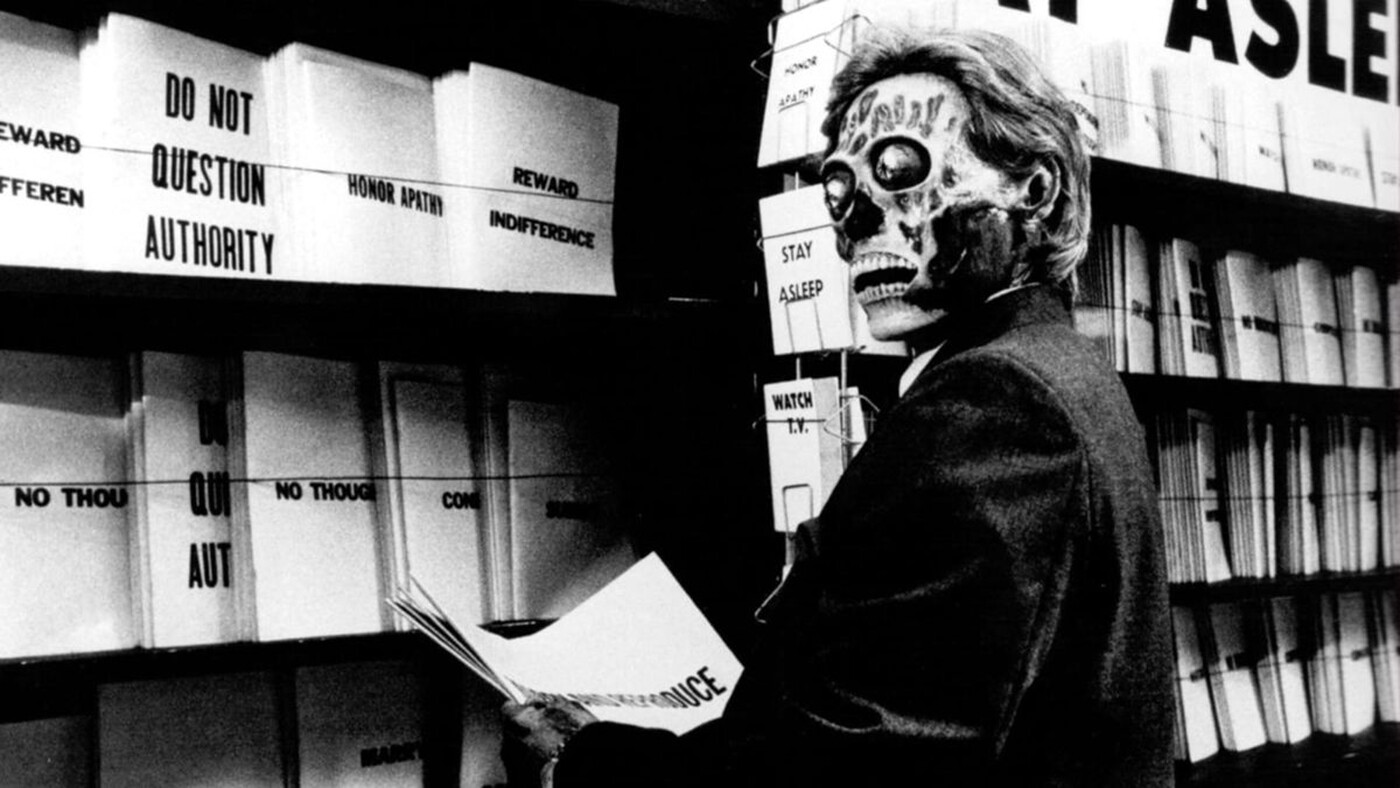

Seeing is a political act. Who has the right to visualize what and how? I am interested not just in the ways that scientists, artists, and people in their everyday lives have made the virus visible but also in what other processes—both historical and contemporary—viruses make visible.

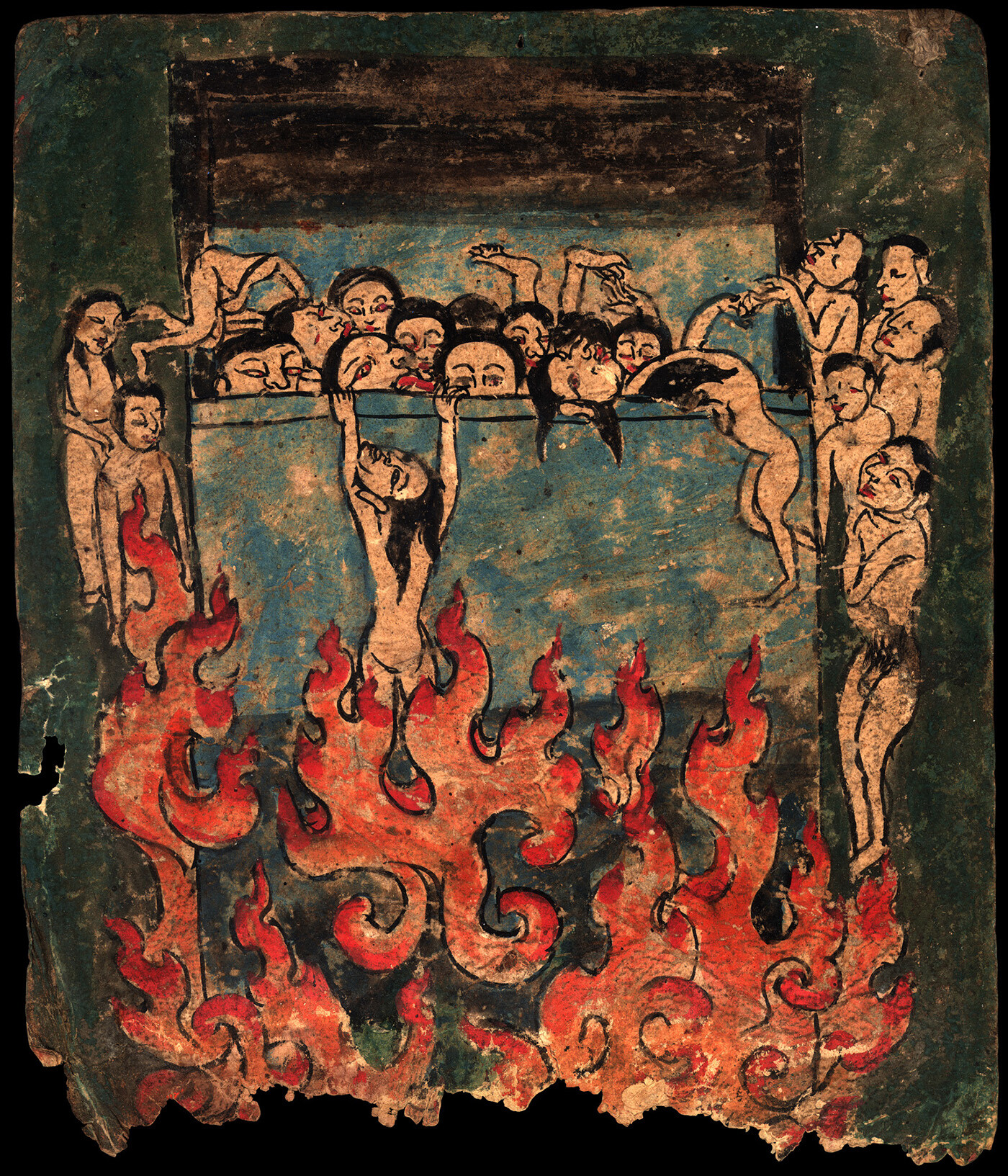

Death by a thousand cuts is the province of relentlessly exposed and/or targeted, otherwise compromised peoples who are wise to their desired or planned termination. It is also the province of thinkers richly equipped with a theoretical imagination toward a species terminus, one that has been rationally preordained by climate change’s inevitabilities, allowing that teleology to predominate all other narratives of vulnerability. But is a species terminus fairly labeled “death”?

You think a dive into Covid conspiracy theory unreality couldn’t happen to you—I’m not so sure. Didn’t many of us not long ago confidently assert in the linguistic turn that the world was created entirely through language and discourse? With enough time to do our “own research” and few boundaries around the vectors critique can take, one might end up joining a “great derangement” rather than exposing hidden truths. Isn’t it awfully easy to lose sight of the real?

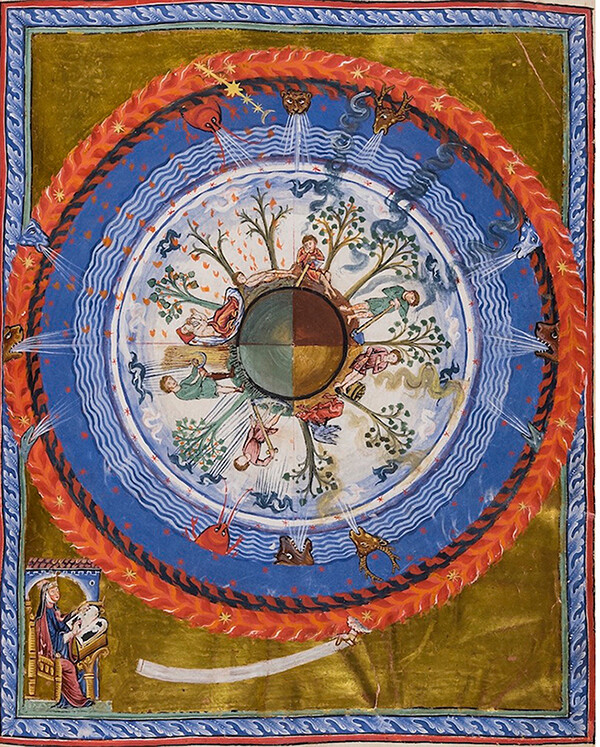

Waste’s hauntology of bodies as ecosystems, and the alterlives created in the wake of harmful or undesirable exposures, help to illuminate viral junk and its pluripotent capacities within genomes. It is a reminder that microbes, viruses included, are us. Ancient viral exposures remaining in the genome may play a continued role in gene expression or viral memory.

We become intimate through the air we share. With SARS-CoV-2, one need mingle no bodily fluids, only breath: the atmosphere is our medium of intimacy. In the biopolitics of respiration, what we are sharing is effectively our insides.

Viruses are not like spaceships, and cells are not just like twentieth-century semitrailer trucks, armored vehicles, or passenger jets whose resources can be plundered and whose operators can be coerced into unwanted journeys. As with many apparently innocuous explanatory tropes, this figure of the viral hijacker perhaps hides as much as it reveals.

It would be easy to react with disgust to this scene. Here we were, in a place that smelled like a dank alleyway in New York, where people were apparently exposing themselves to viruses that had the potential to spawn a new pandemic. Lingering in this multispecies contact zone, we contemplated the ongoing exchanges of viruses between people and other species, while thinking with care about the religious significance of the prayers.