Dream House

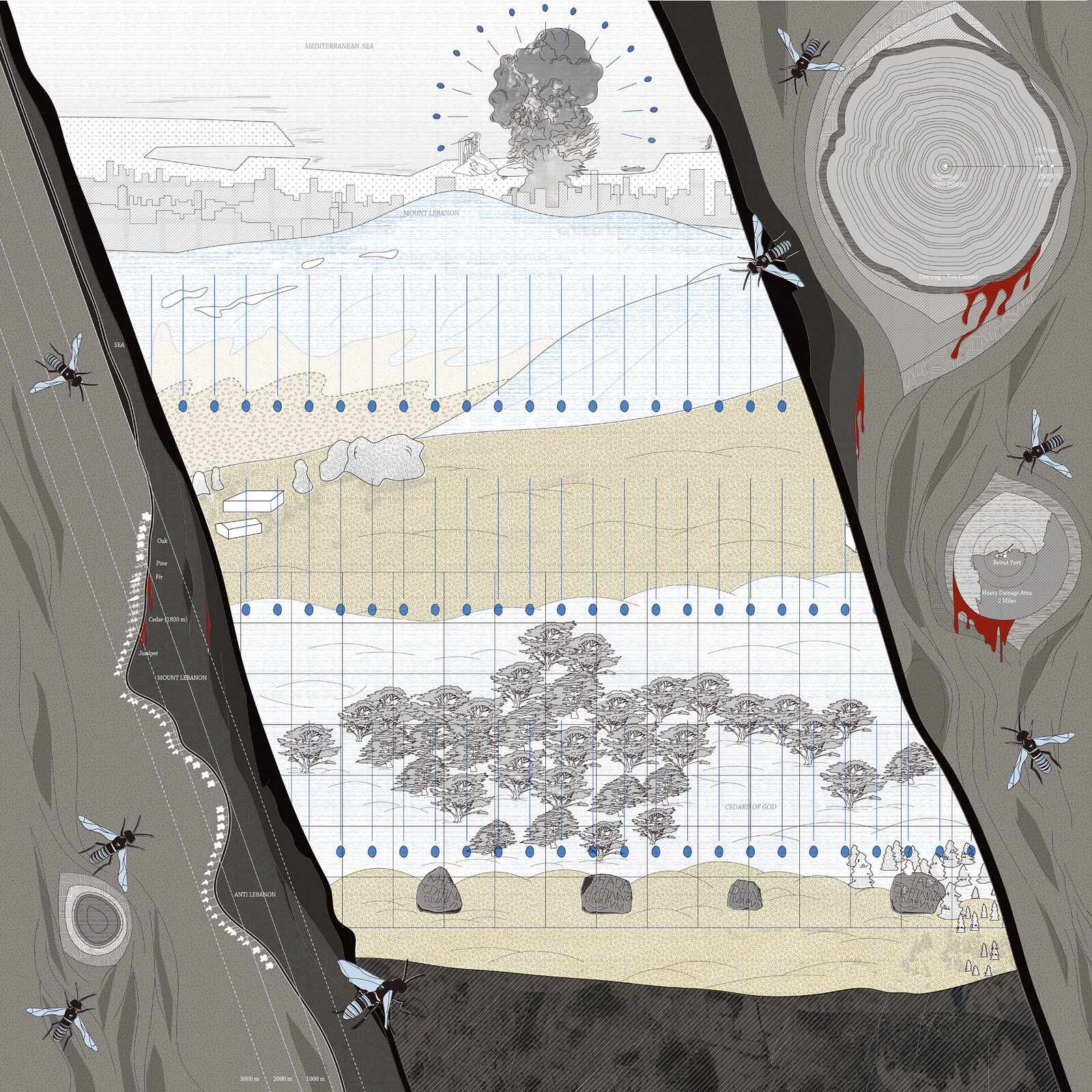

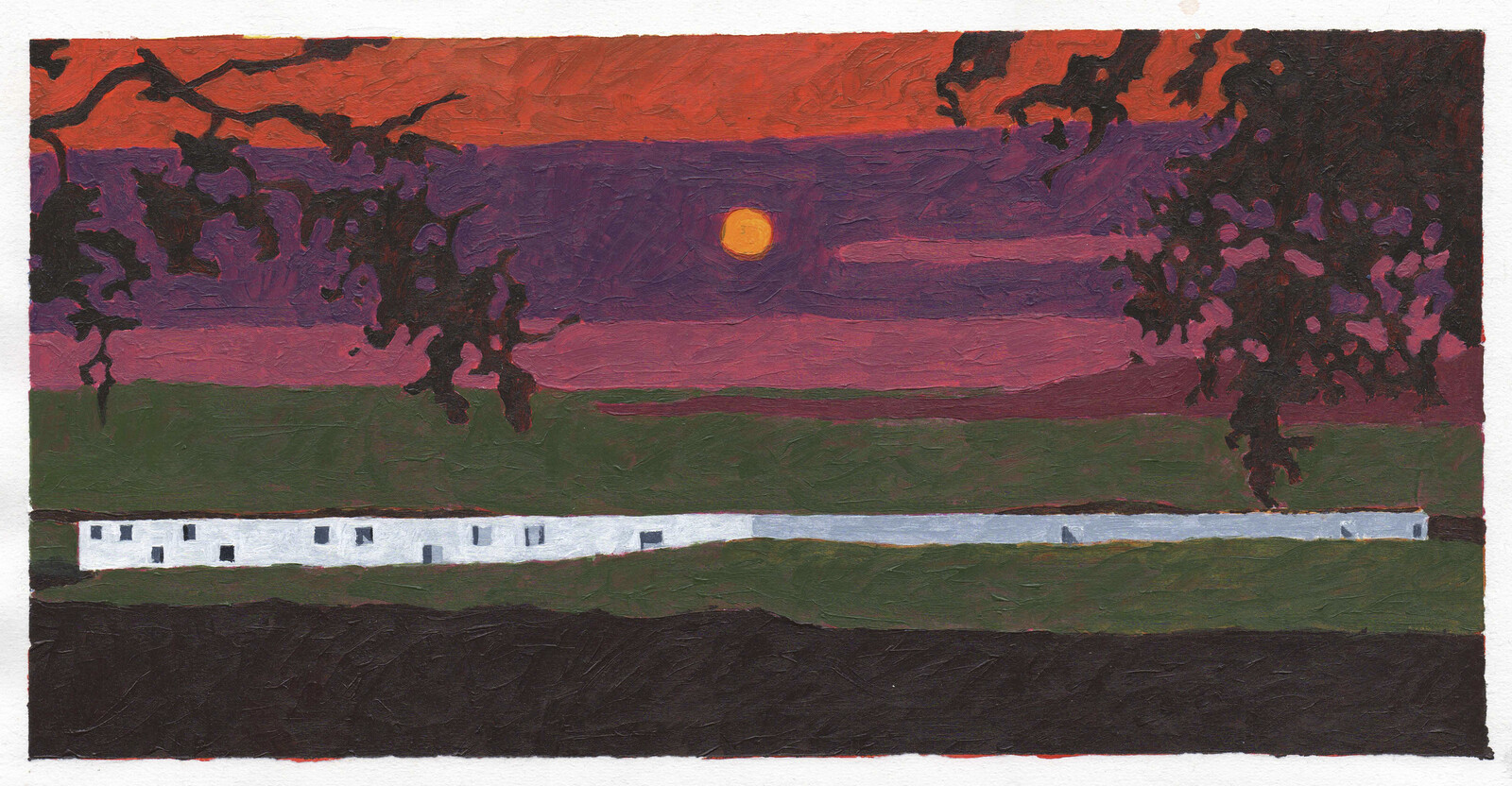

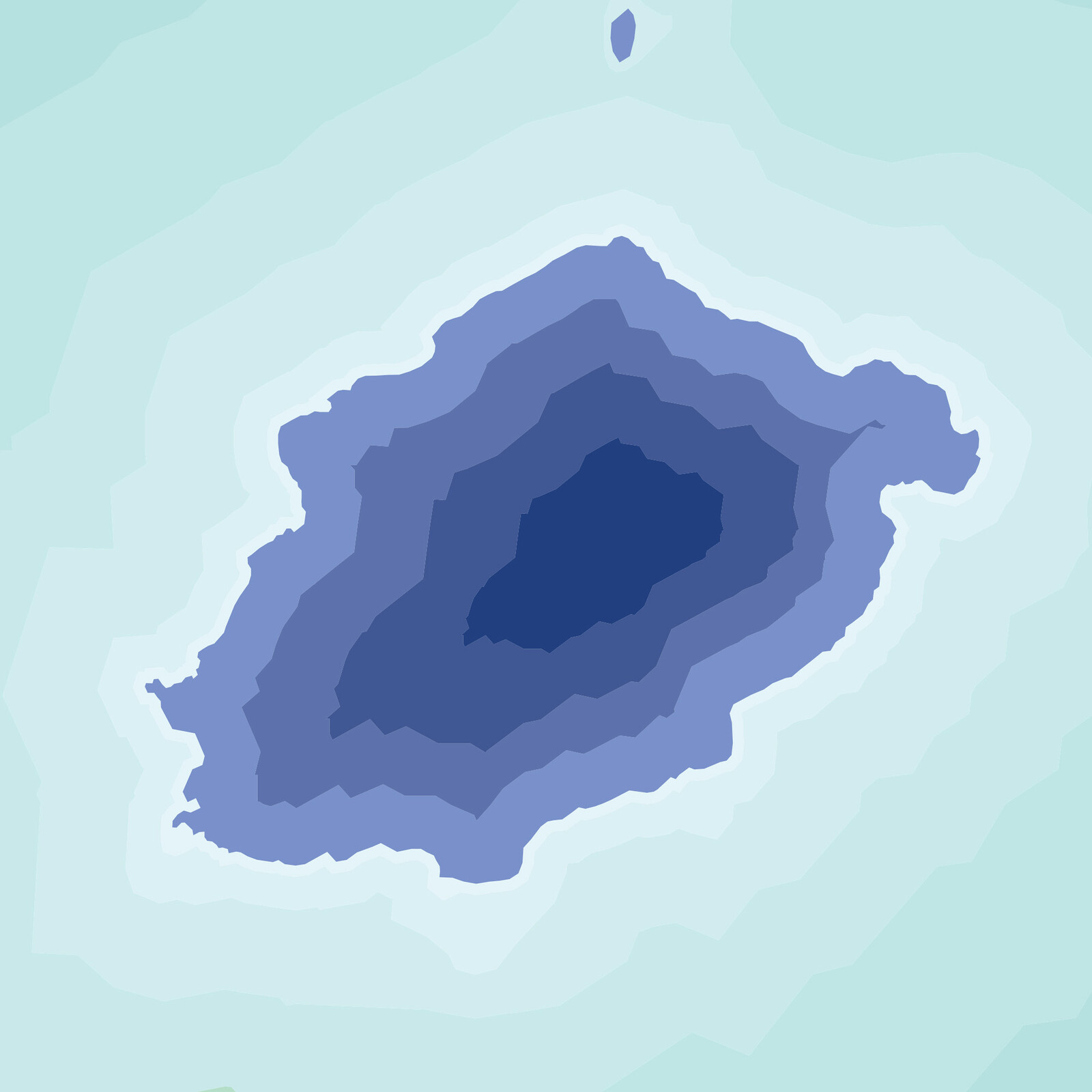

The Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh tells a story of the journey to the Cedar Forest. On each day of the six-day journey, King Gilgamesh has admonitory dreams. On the third night, Gilgamesh dreams of a volcano erupting:

The skies roared with thunder and the earth heaved,

Then came darkness and a stillness like death.

Lightning smashed the ground and fires blazed out;

Death flooded from the skies.

When the heat died and the fires went out,

The plains had turned to ash.

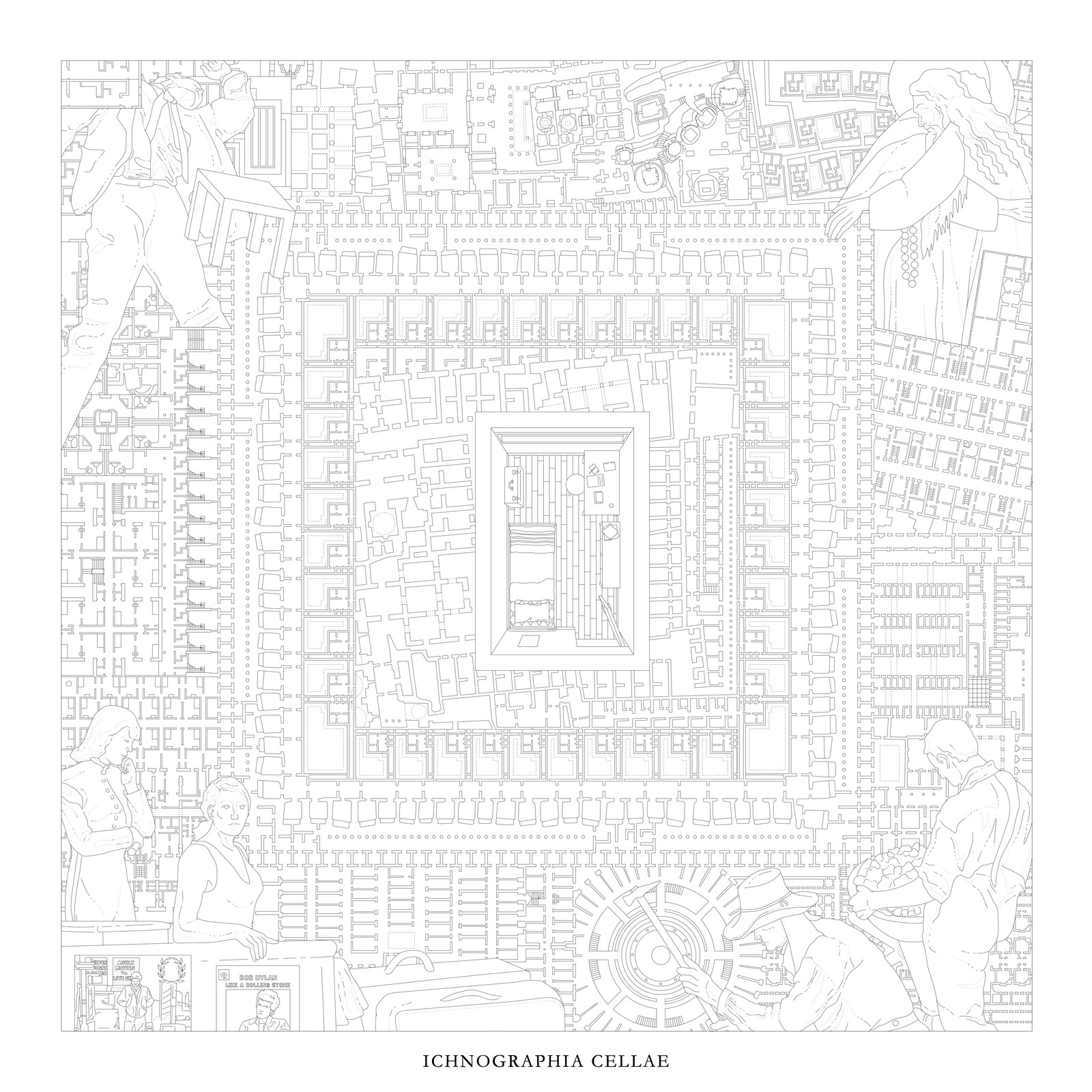

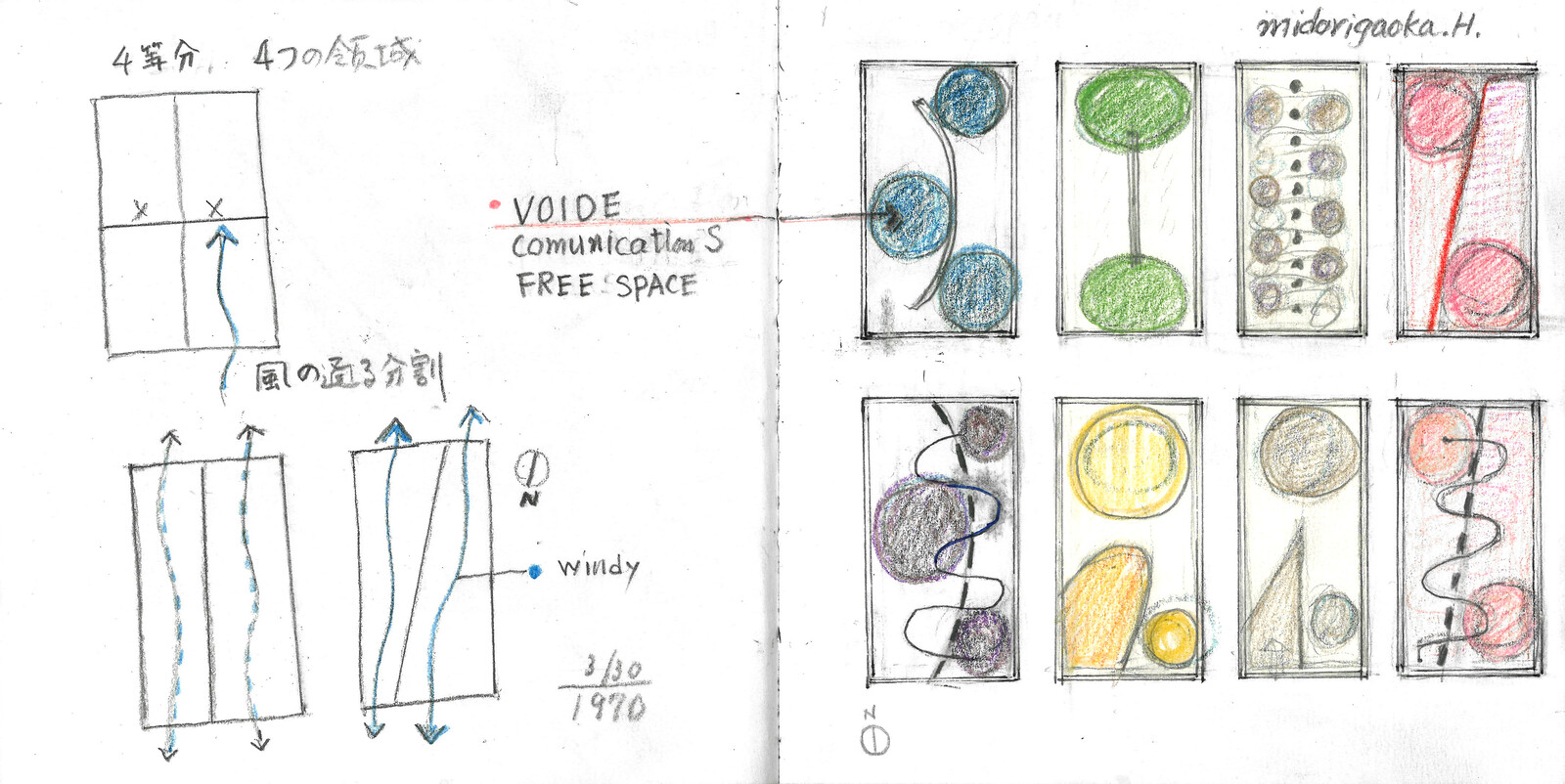

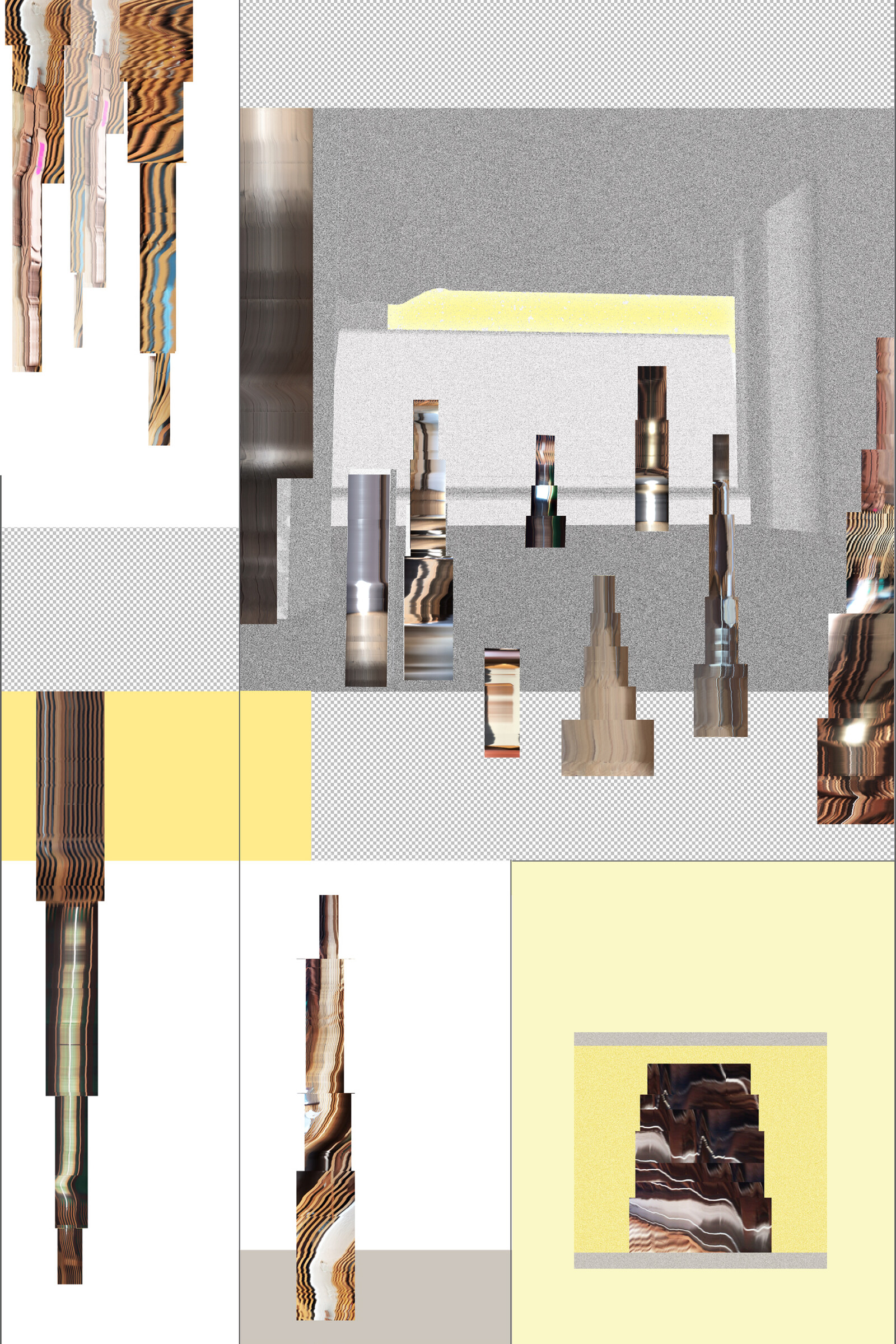

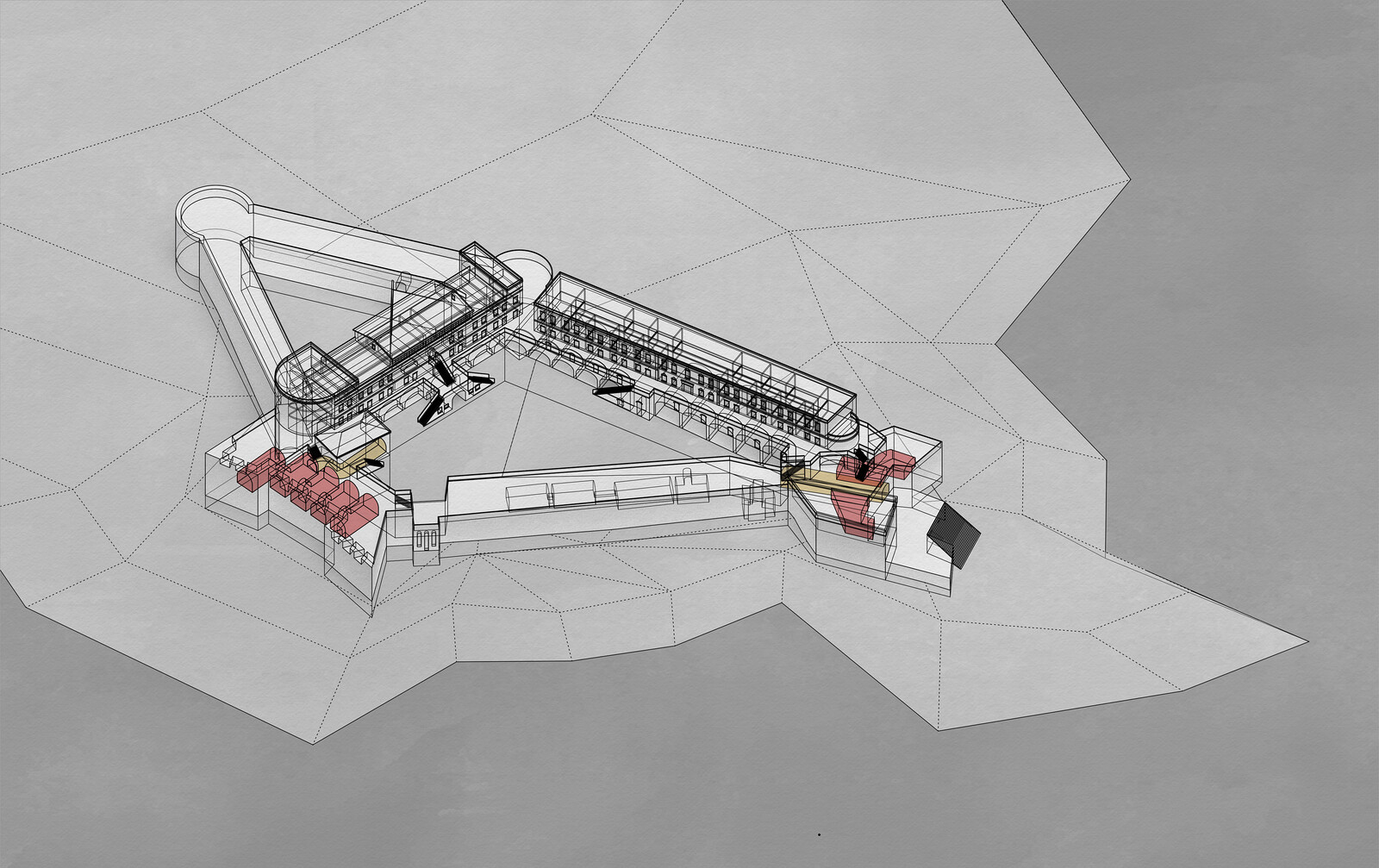

The dreamscape is hostile and profoundly stark: violent winds through deep mountain gorges, choking clouds of dust from the ground split asunder, wild beasts, oppressive weight of earth, panic and tremors, blast of lightning, blaze of fire, thick rain of profuse, deadly ash. These are dreams whose vastness is only amplified by contrast with the smaller, humbler, and implicitly more fragile space that would contain them—that of the Dream House. Gilgamesh sleeps inside the circle on the floor. Around Gilgamesh are his travel murals—the encounter with his sidekick Enkidu and the anticipation of his upcoming confrontation with Humbaba, the guardian of the Forest, who interprets the death and terror of the volcanic dream as a symbol of victory over mortality and monsters.

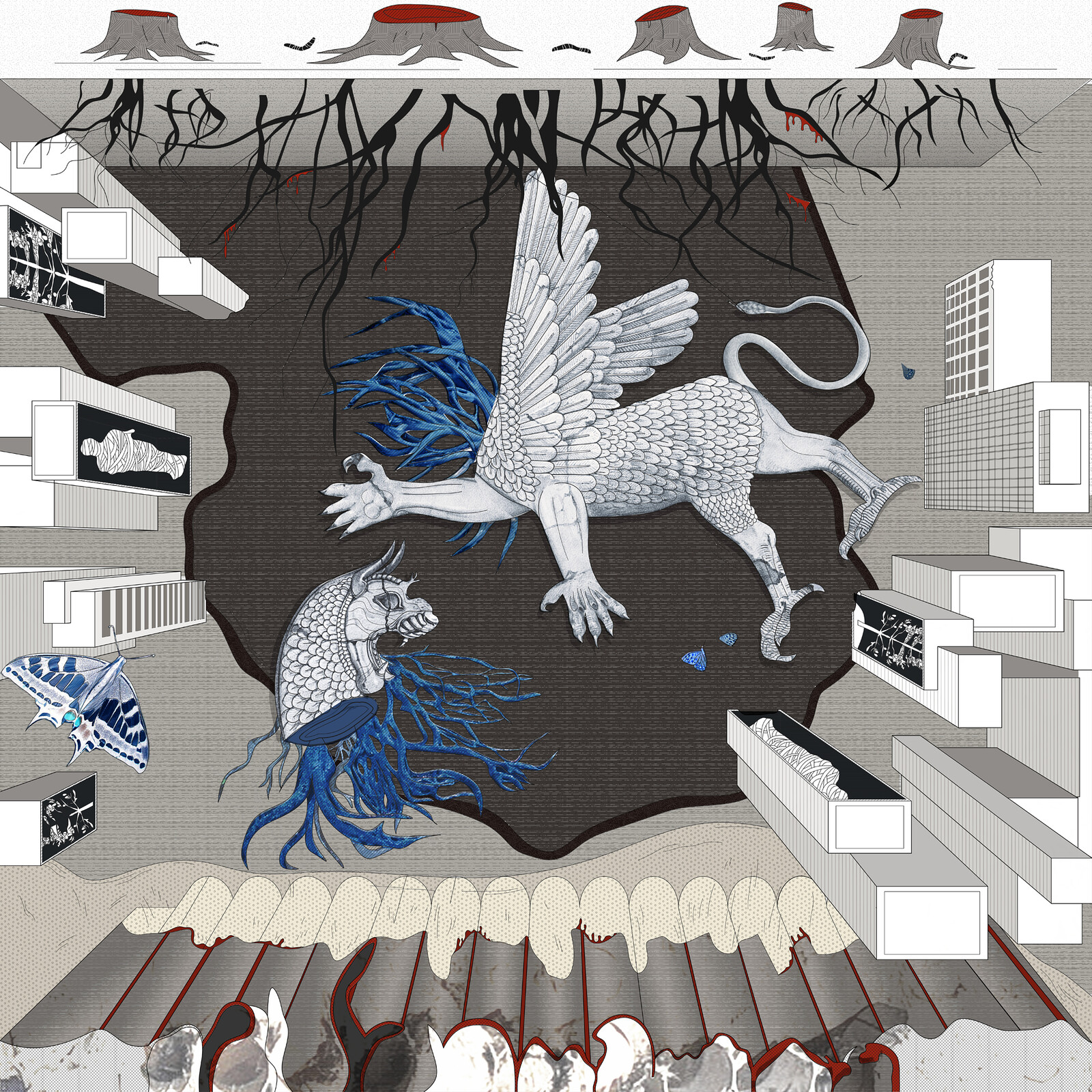

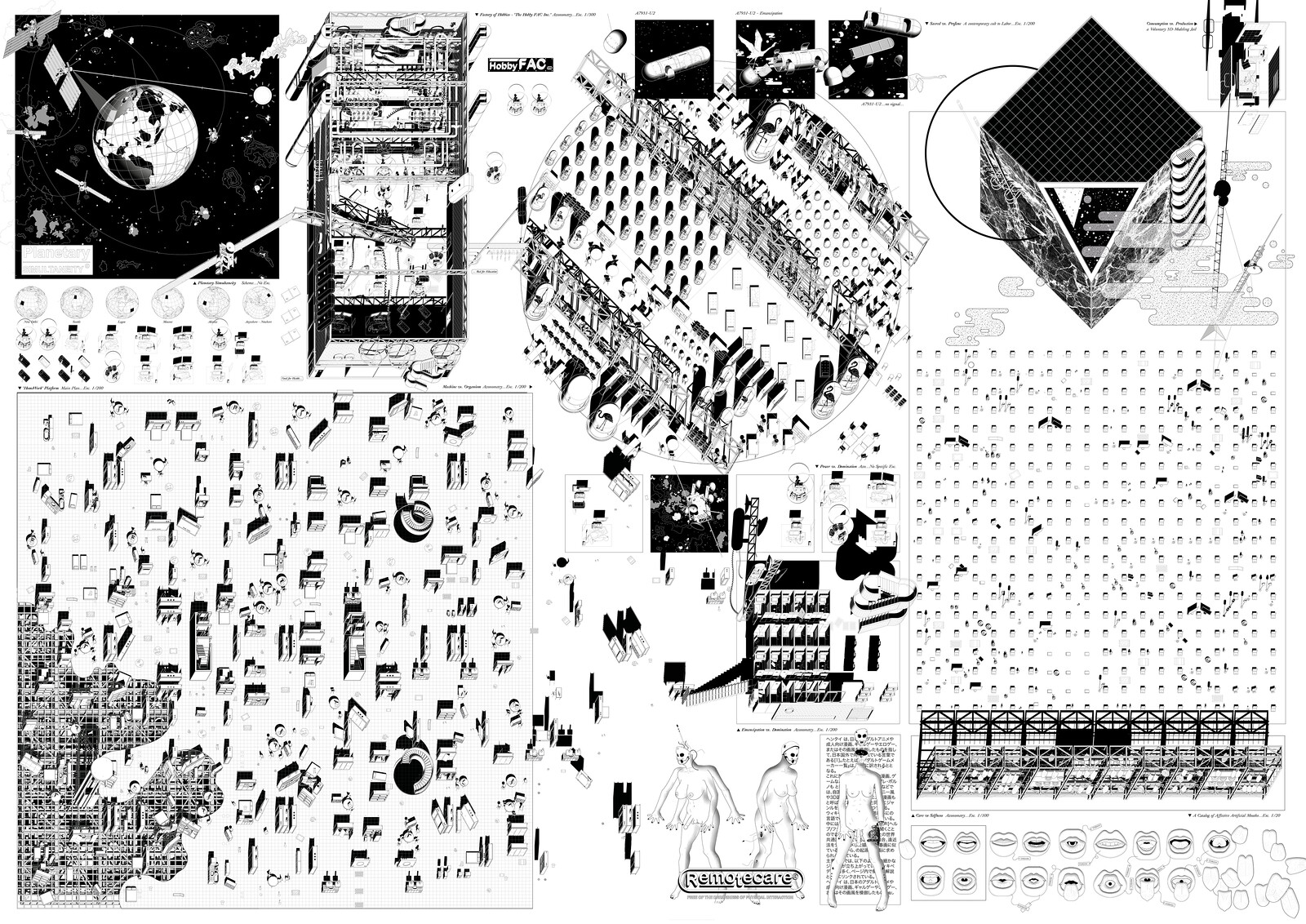

The Silent Demise of Humbaba

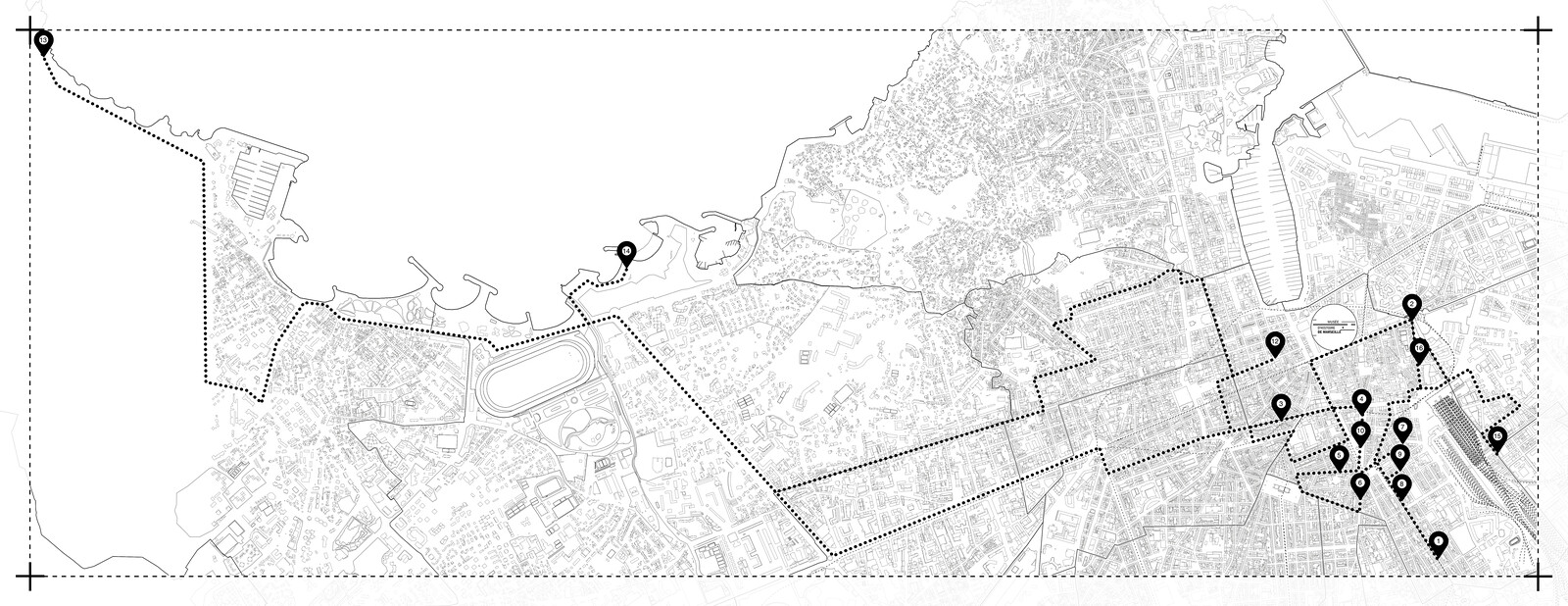

Humbaba, surnamed the Terrible, was a monstrous giant with staring eyes and the face of a lion. Gilgamesh severs the head of the guardian of the forest and chops down many of its trees, turning them into fine wood for the doors of the great Mesopotamian temples. Yet the dream continues to haunt Gilgamesh. He marvels at the cedar trees’ height and breathes in their incense, but all he can think and feel is the earth is shaking amidst the noise of thunder and lightning, with fire and ashes fall from the sky. He hears some sort of eruption, like a volcano, and glimpses the mangled Beirut grain silos. Maybe it was Ishtar’s fury burning inside her immortal heart. After all, Gilgamesh had turned down the goddess’s advances to become her lover. Her furor unleashes the Bull of Heaven to wreak vengeance on Gilgamesh and his city.

Father, let me have the Bull of Heaven

To kill Gilgamesh and his city.

For if you do not grant me the Bull of Heaven,

I will pull down the Gates of Hell itself,

Crush the doorposts and flatten the door,

And I will let the dead leave

And let the dead roam the earth

And they shall eat the living.

The dead will overwhelm all the living!

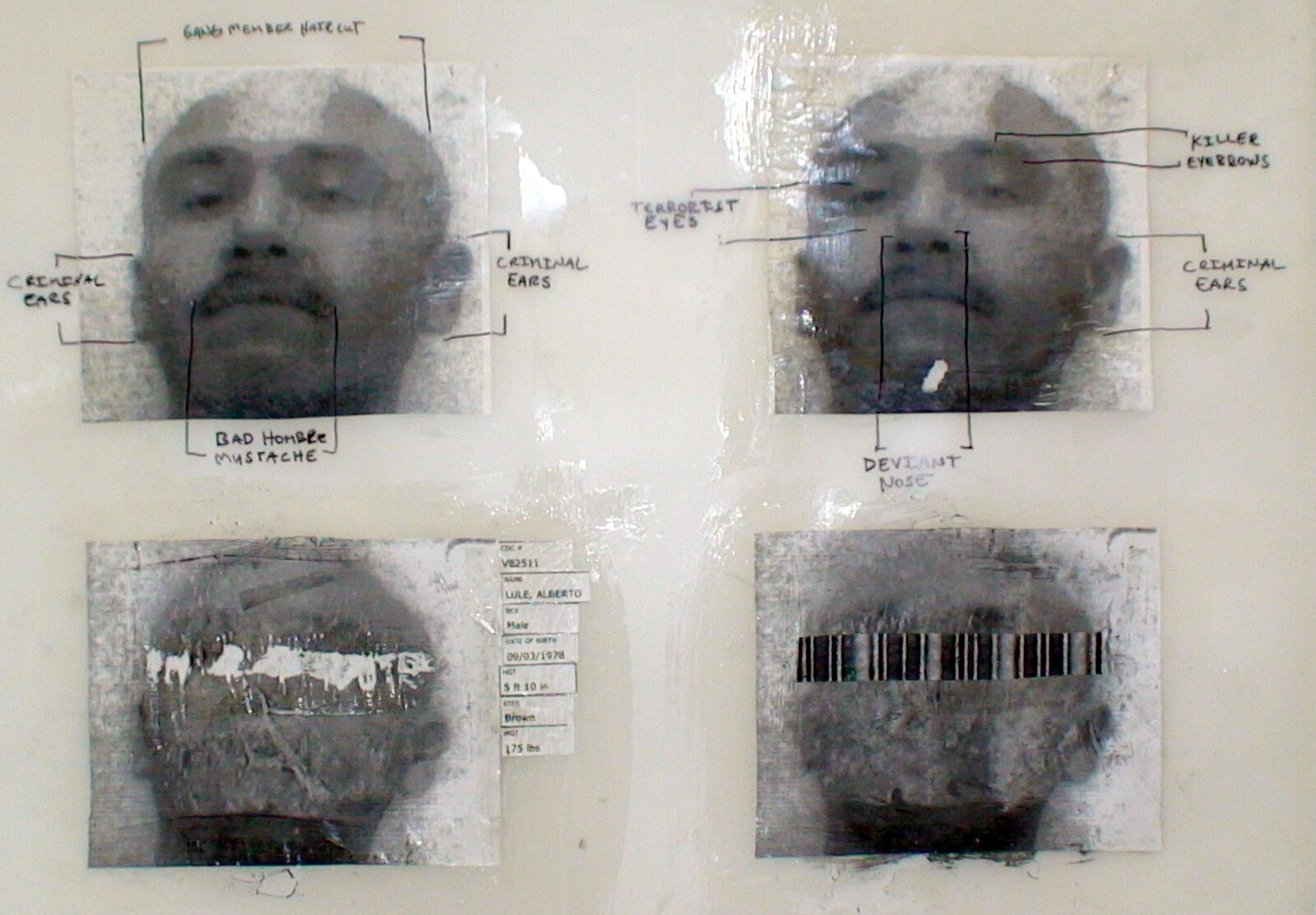

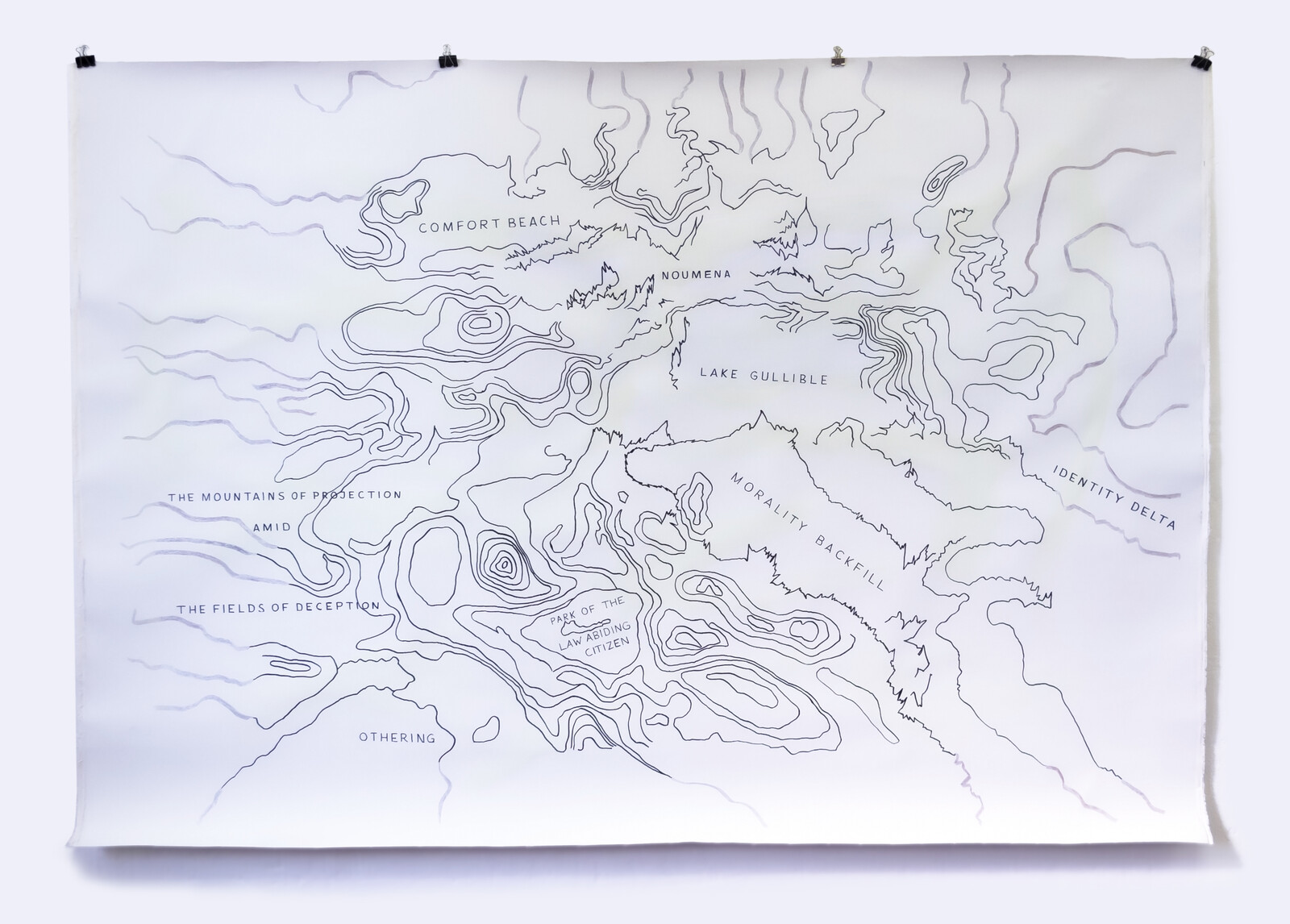

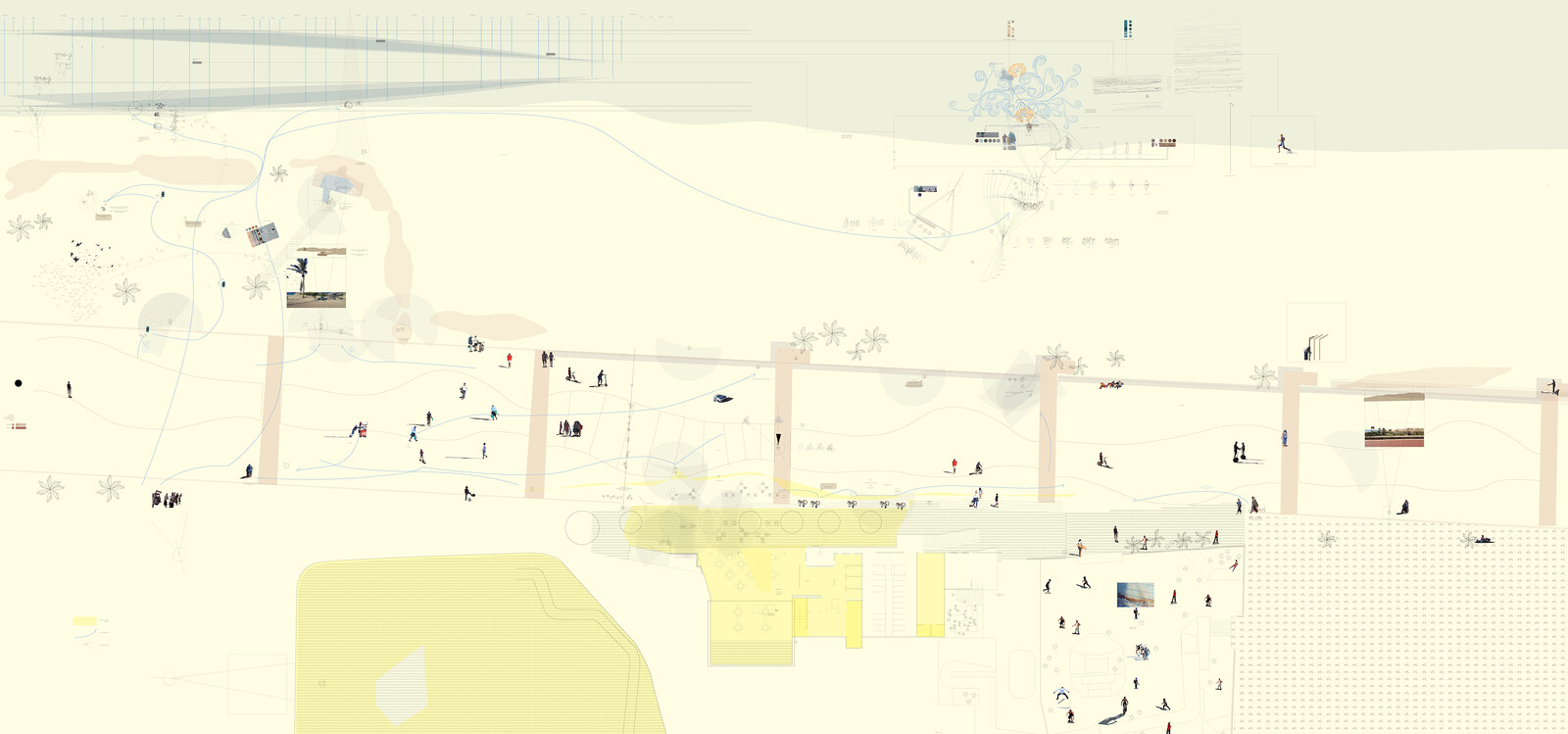

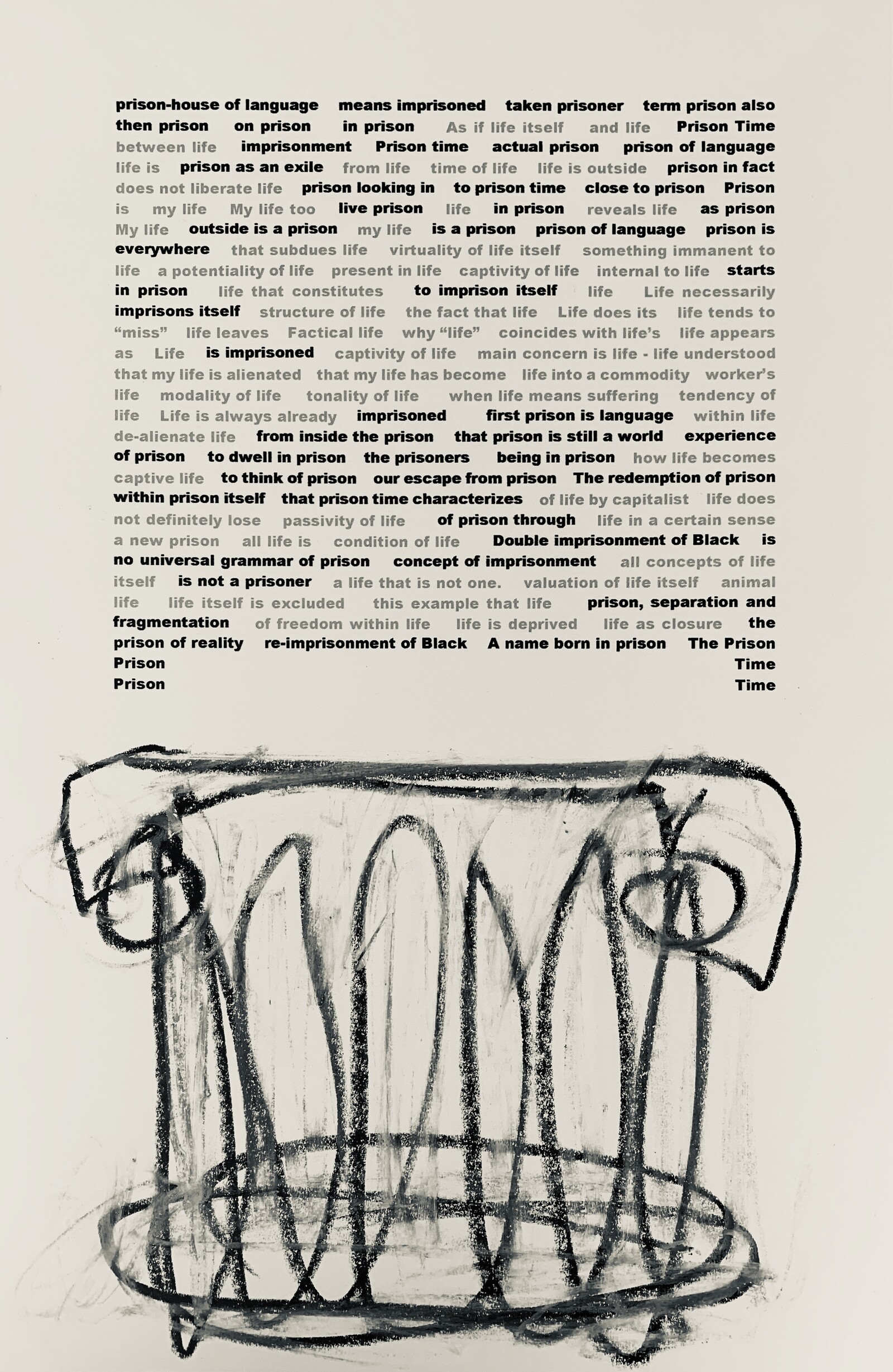

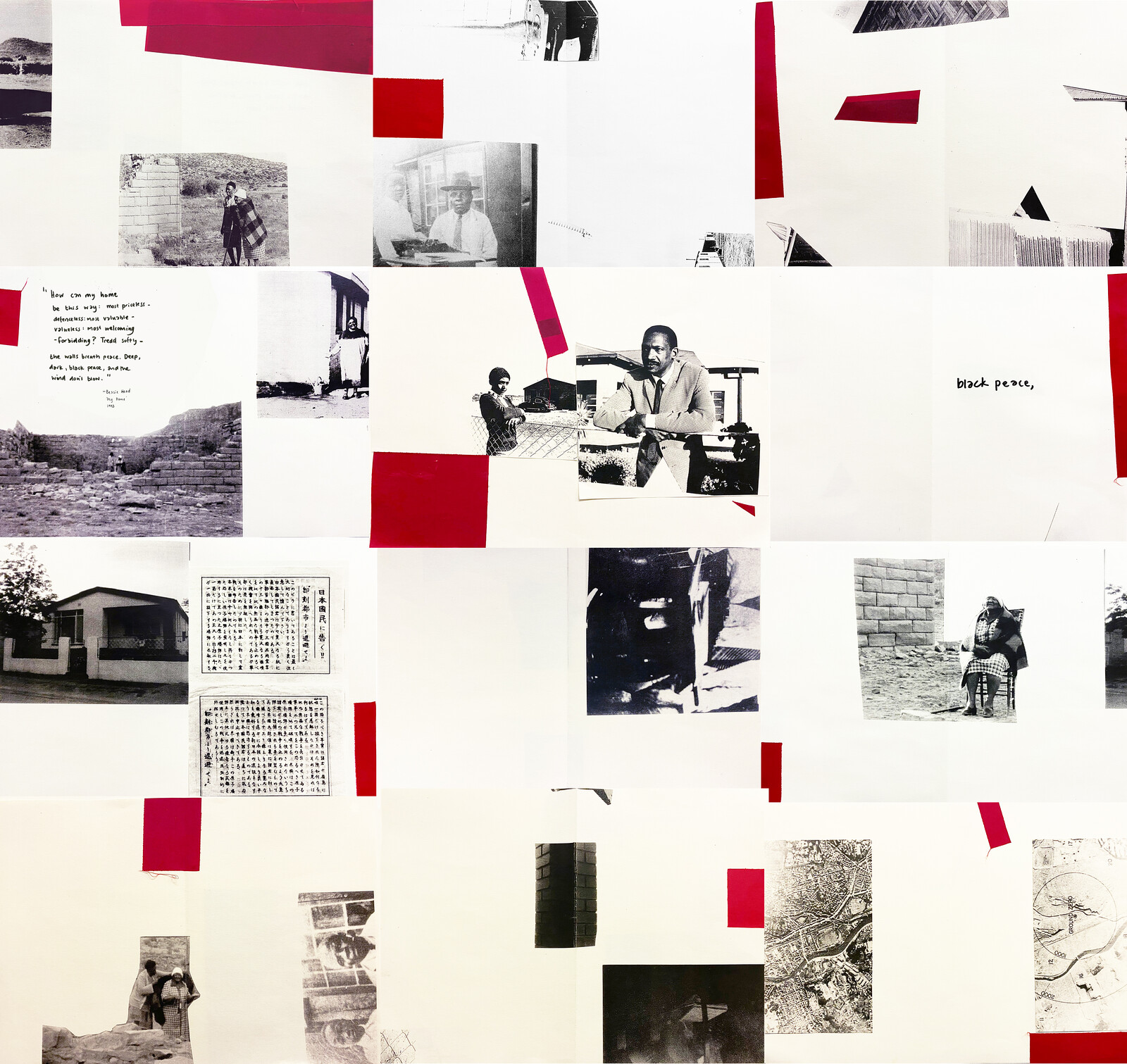

Bleeding Sap

When you see a tree bleeding sap, you know there is a problem. And in such raw spaces as the Land of the Cedars, things survive within the strong ritual boundaries that myth erects. In the eyes of those who meet Gilgamesh, his appearance is an index of the toils of the journey—how long he has wandered, amidst what emissions and debris, through what sights, and with what suffering. Gilgamesh admits that he is afraid of death, although it may be a fear of early or tragic death. His life narrative unfolds within the space between two trees. Seeing the impermanence of life, he discovers the blue grain seedings falling from the sky. Ammonium nitrate is, after all, a chemical high-nitrogen fertilizer used in agriculture. The right to kill metamorphoses into a plant of life. The tree sap wraps around a wounded human heart, and feral honey bee colonies swarm all around hollow cedar trees.

[why are your] cheeks [so hollow,] your face so sunken,

[your mood so wretched,] your visage [so] wasted?

[Why] in your heart [does sorrow reside,]

and your face resemble one [come from afar?]

Why are your fingers burnt [by frost and by sunshine,]

[and why do] you wander the wild [in lion’s garb?]

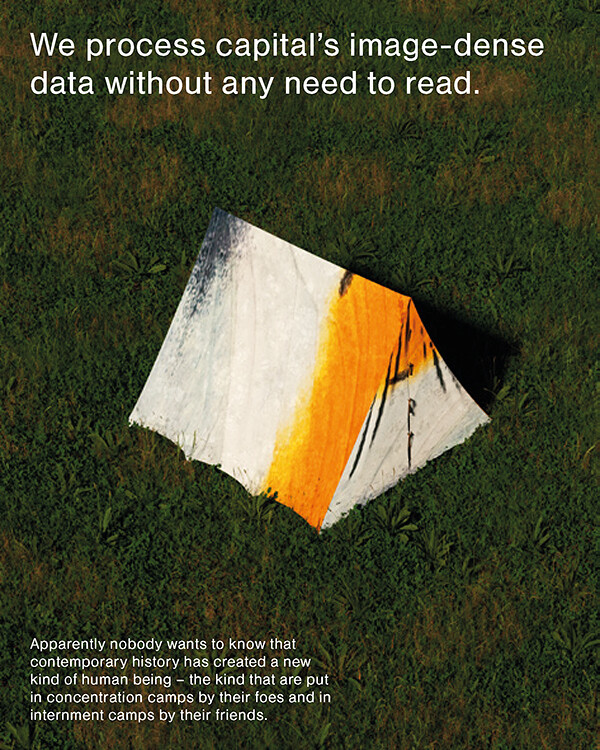

Confinement is a collaborative exhibition curated by gta exhibitions and e-flux Architecture, supported by the Adrian Weiss Stiftung and the ETH Zürich Foundation.