Black desire

Enclosed

Clouded, shrouded, 10, 11, need

Chapter 6

Health

MY PRESENT STATE OF HEALTH

‘My monthly periods have just been continuous this month since the new complication of bronchitis and anaemia and something else I do not know.’

You too.

I said I would return all the books you lent me.

All the books you were looking at for your French project.

He says George in the French way.

These books are very advanced. There are films embedded in them.

Mysterious exotica

Mysterious erotica

And a unity of joy.

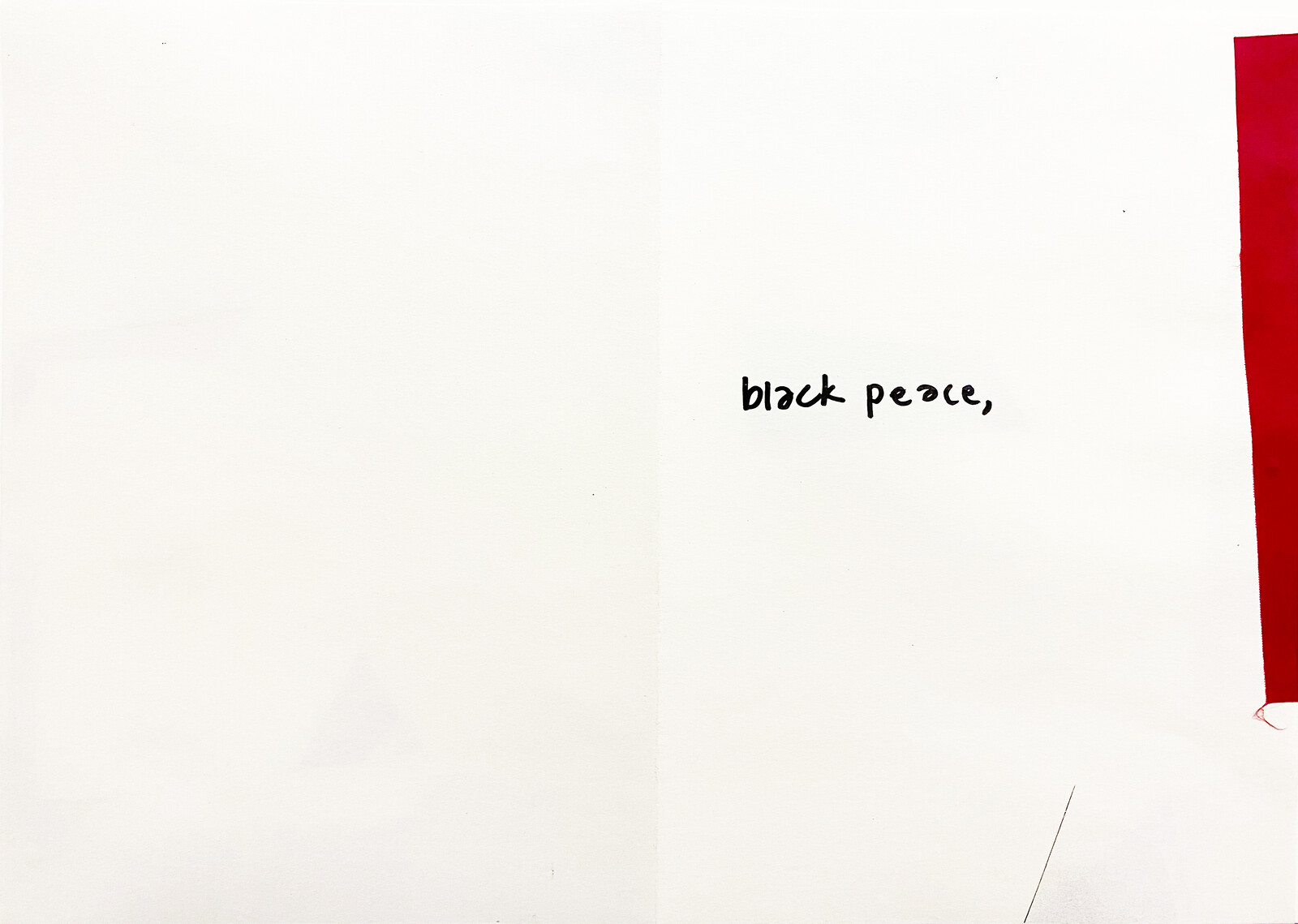

Black peace

on earth

Joy

Where the wind don’t blow

July 15

Kroomen

Krumen, sjoemen, boomen

Sjamen, bogeymen, Bogues

is the one you should talk to about, is the one that writes about

doekom, shaman, obea

obea

Lulu, Vuyo, Lu, Luyolo

Gugu

teacups, teapots, cracked desires at the centre: a pass office. a pass office

a pass

Redness, can the white redden, as the white reddens. Redhill.

July 05

Is sy slams? clearance sale away

Is, is hy slam Is slams clear die way

July 06

his Kruman kiss furnishes the

plain sorrow of the bay of

Black Town

Home. A resting house.

Home. Arresting. Incapable.

Heit my bla.

August 04

I

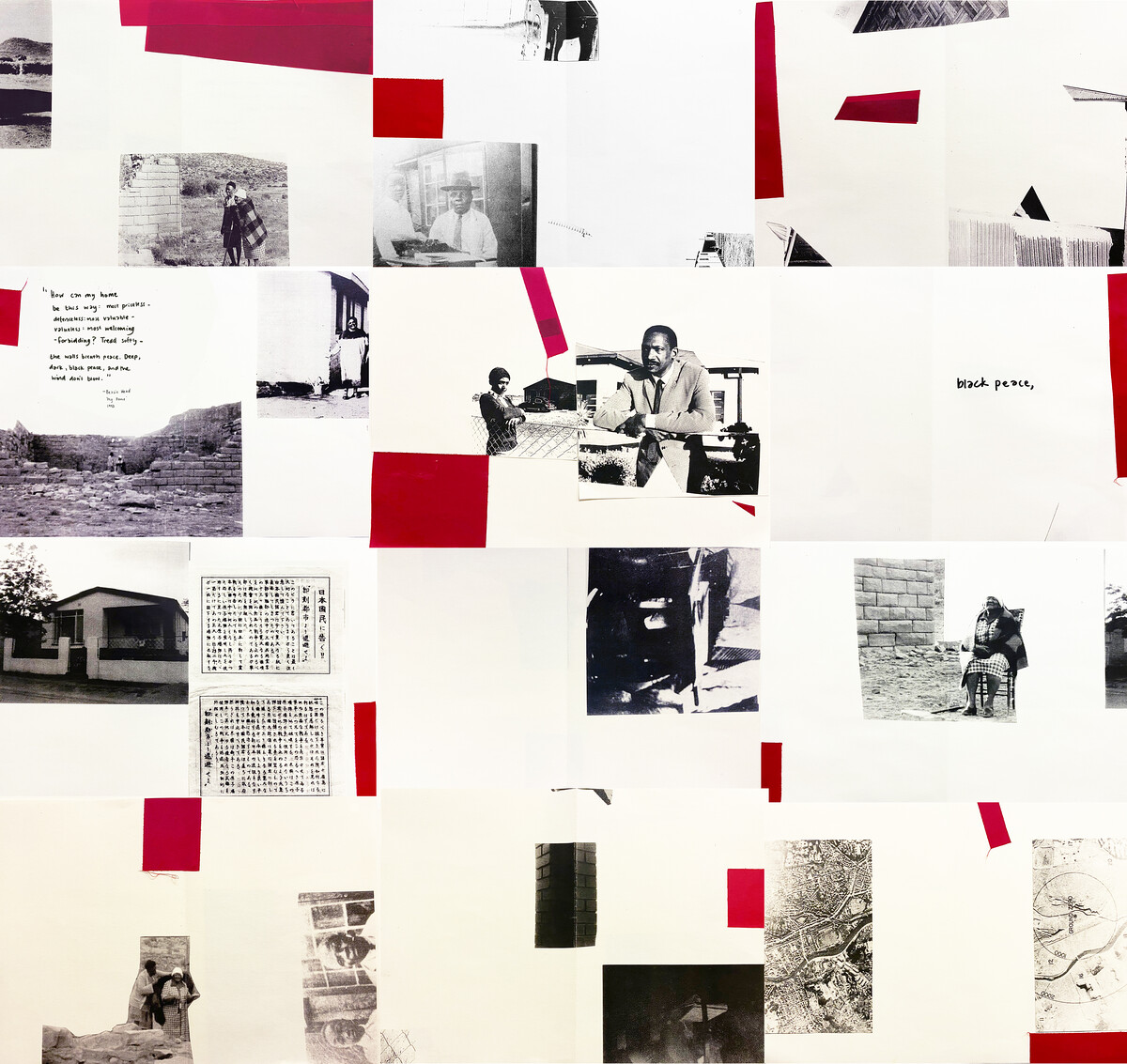

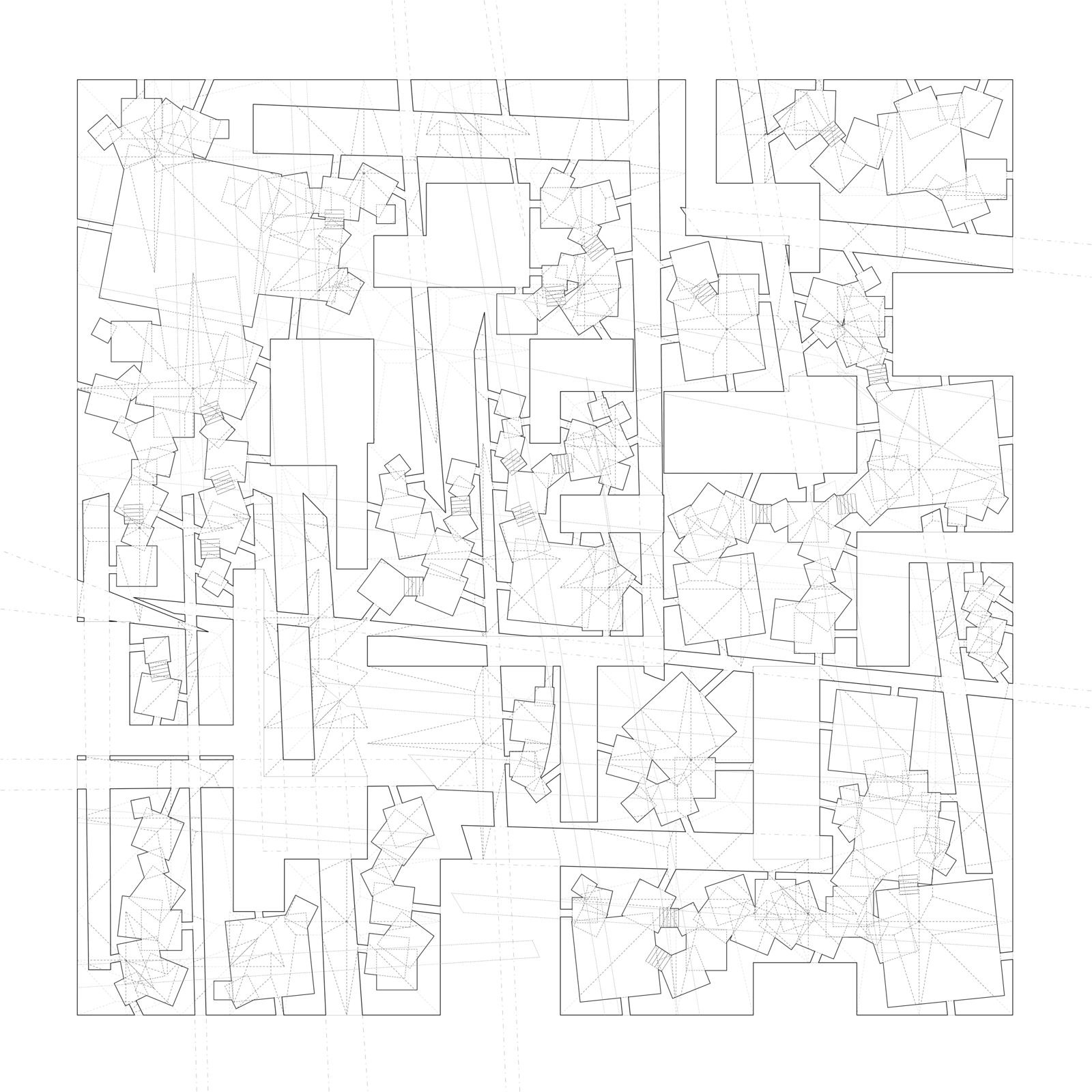

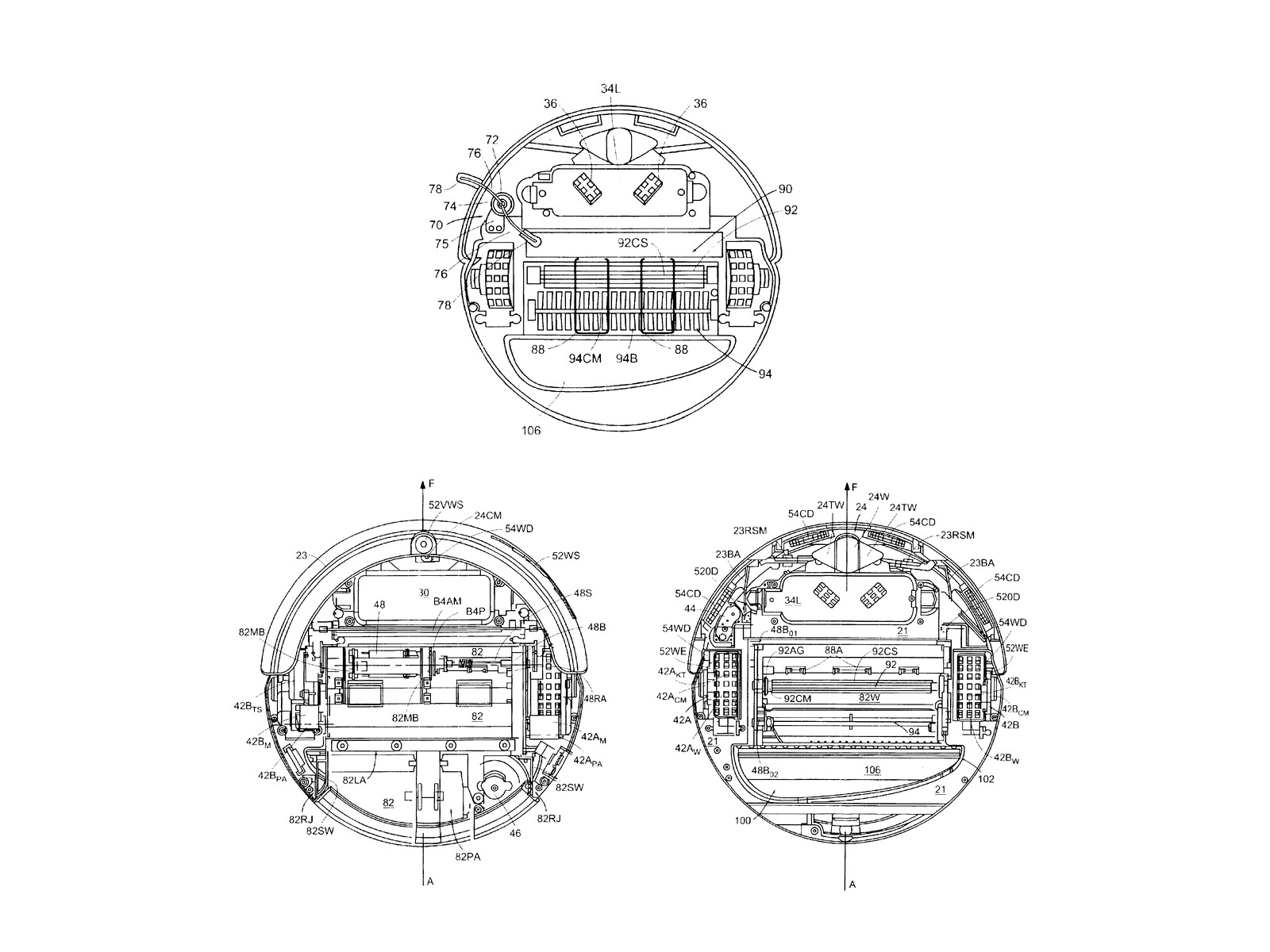

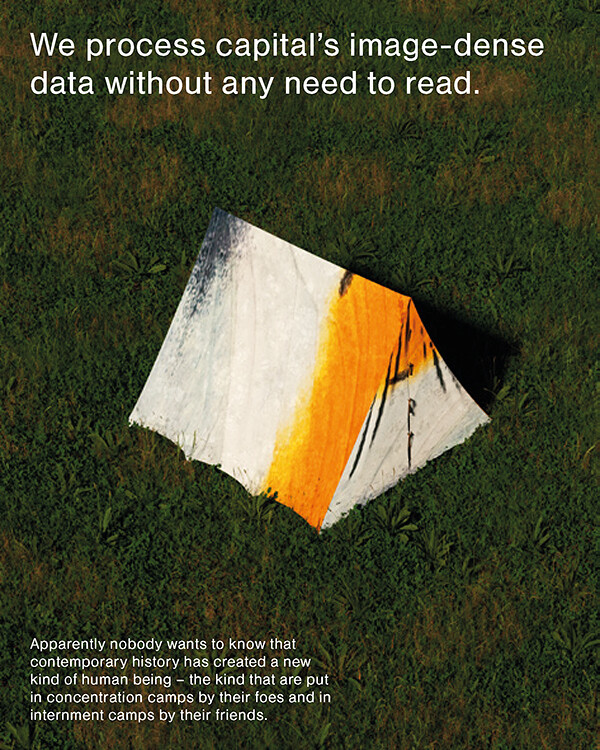

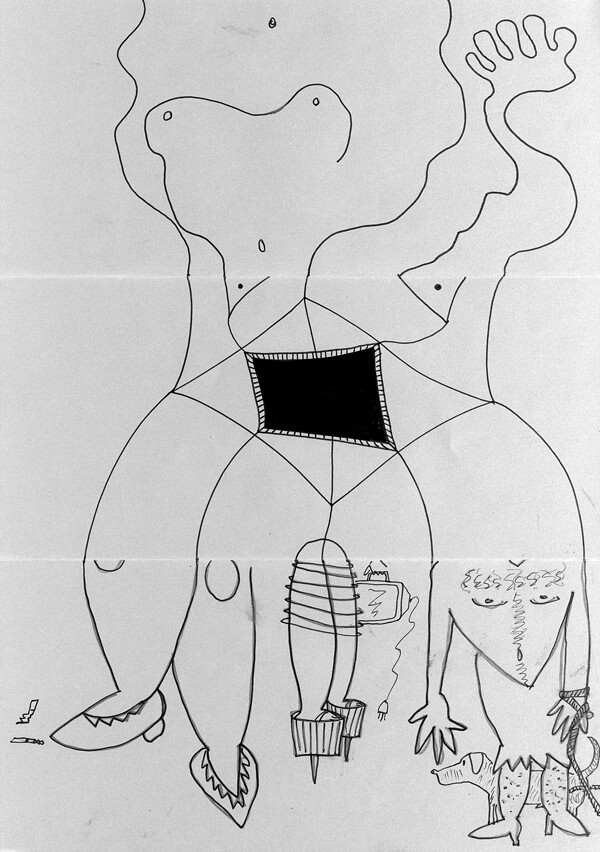

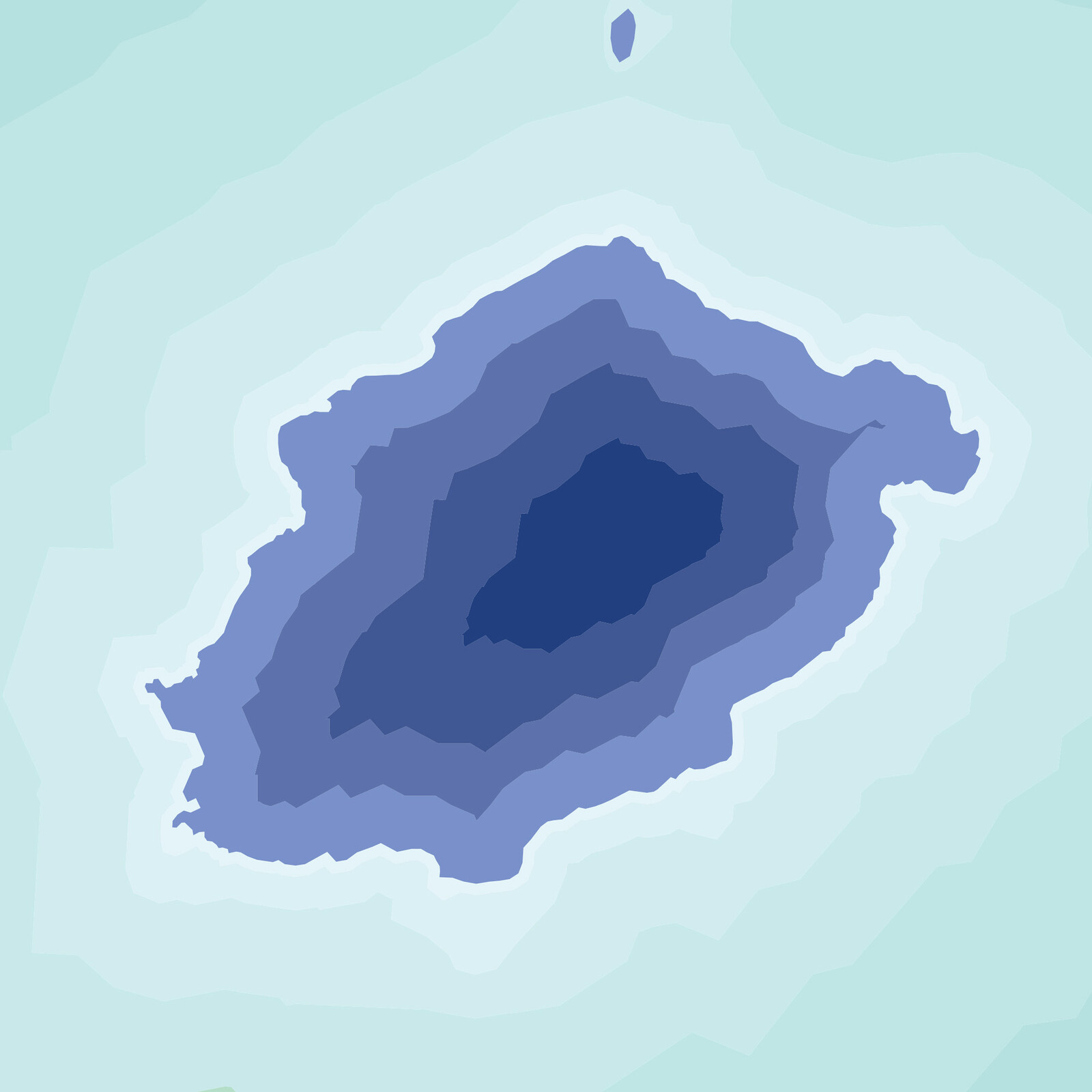

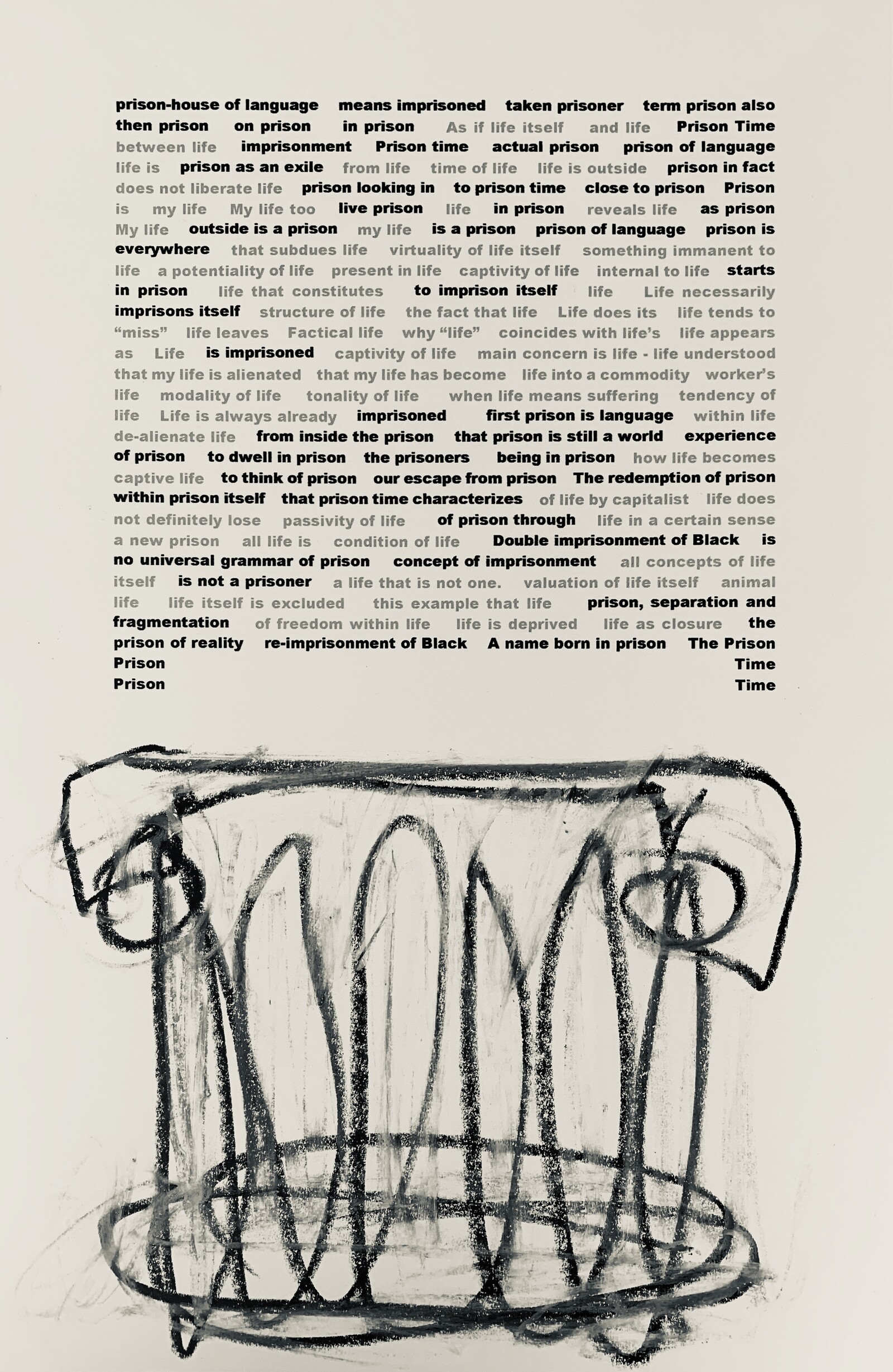

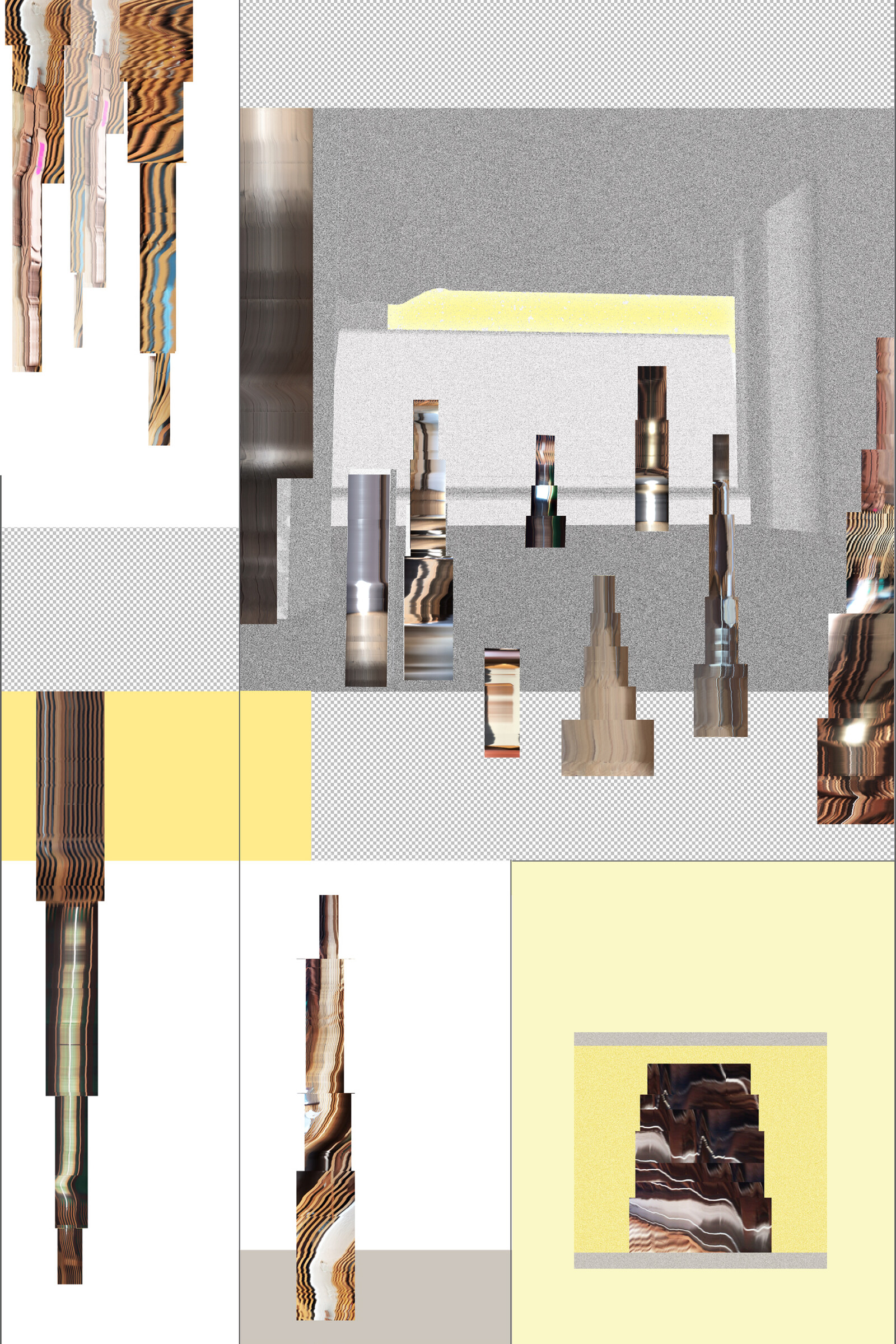

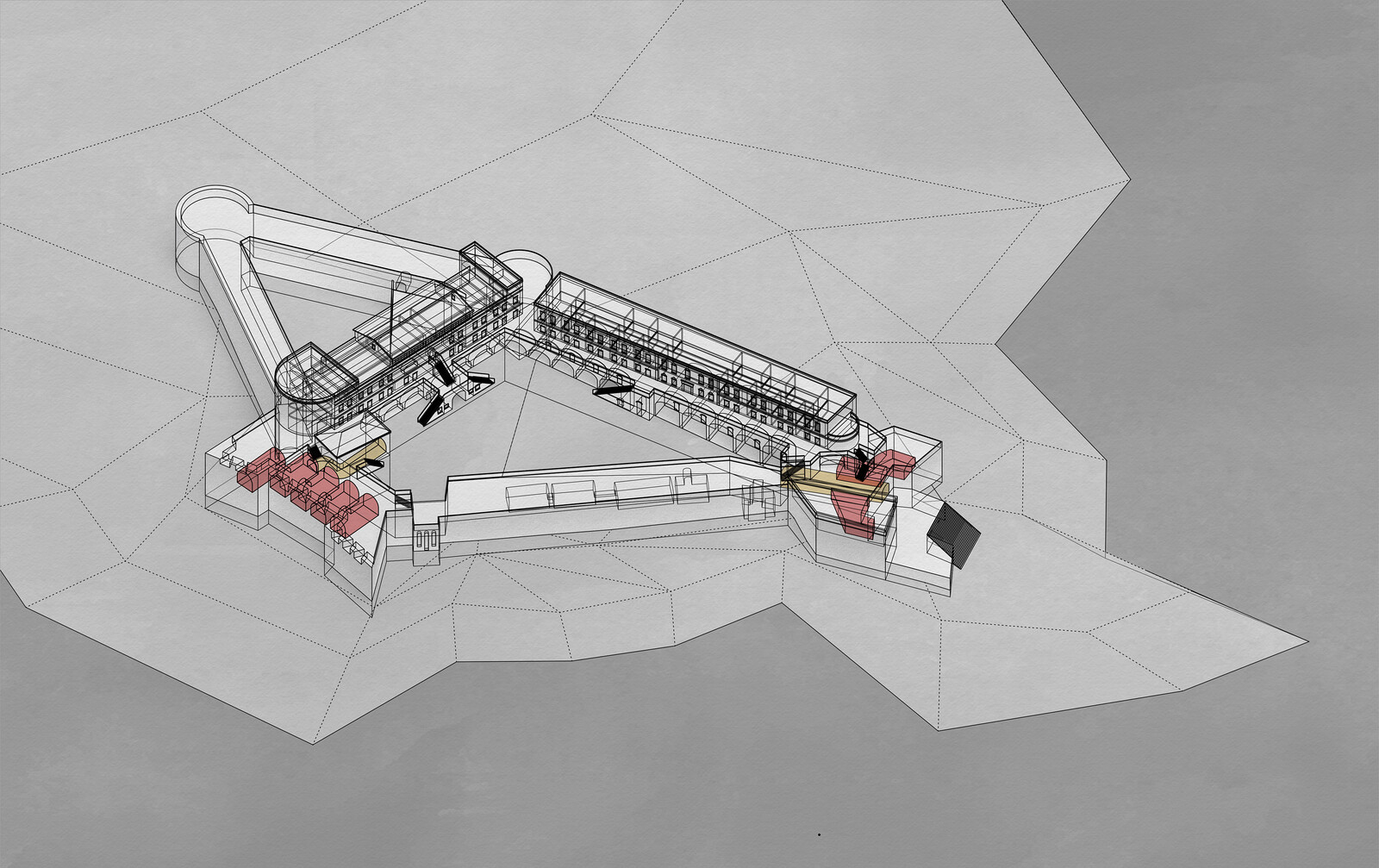

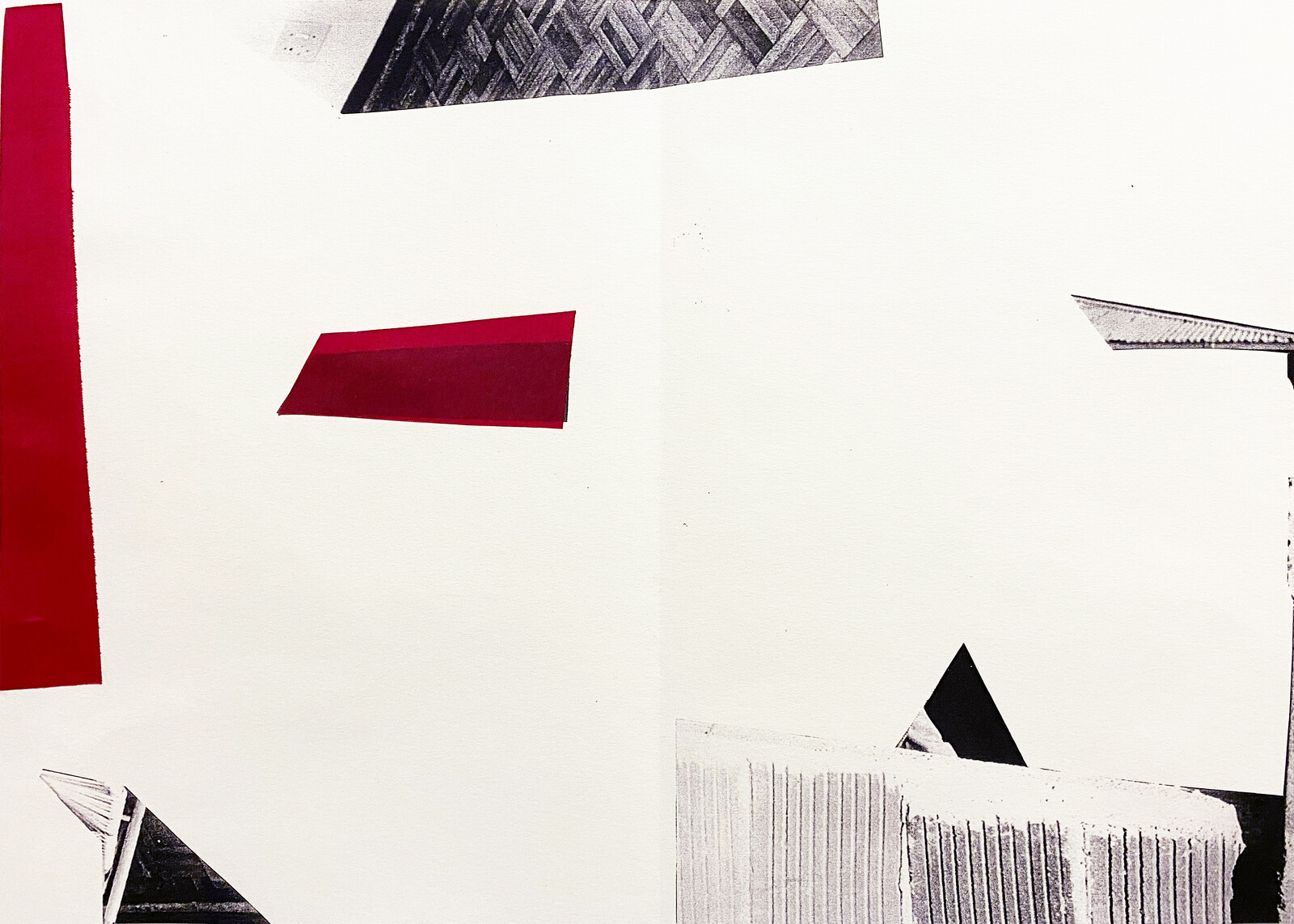

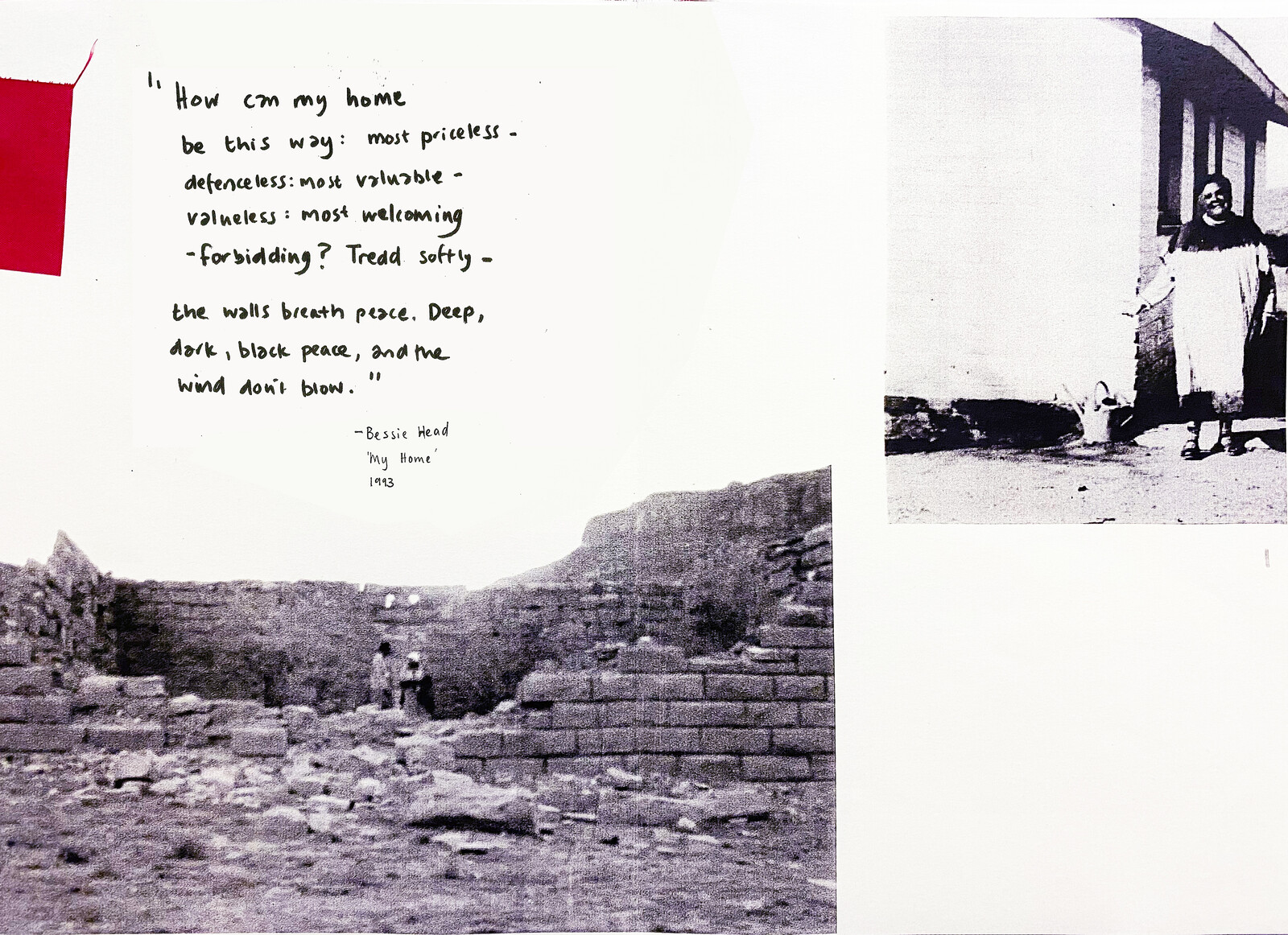

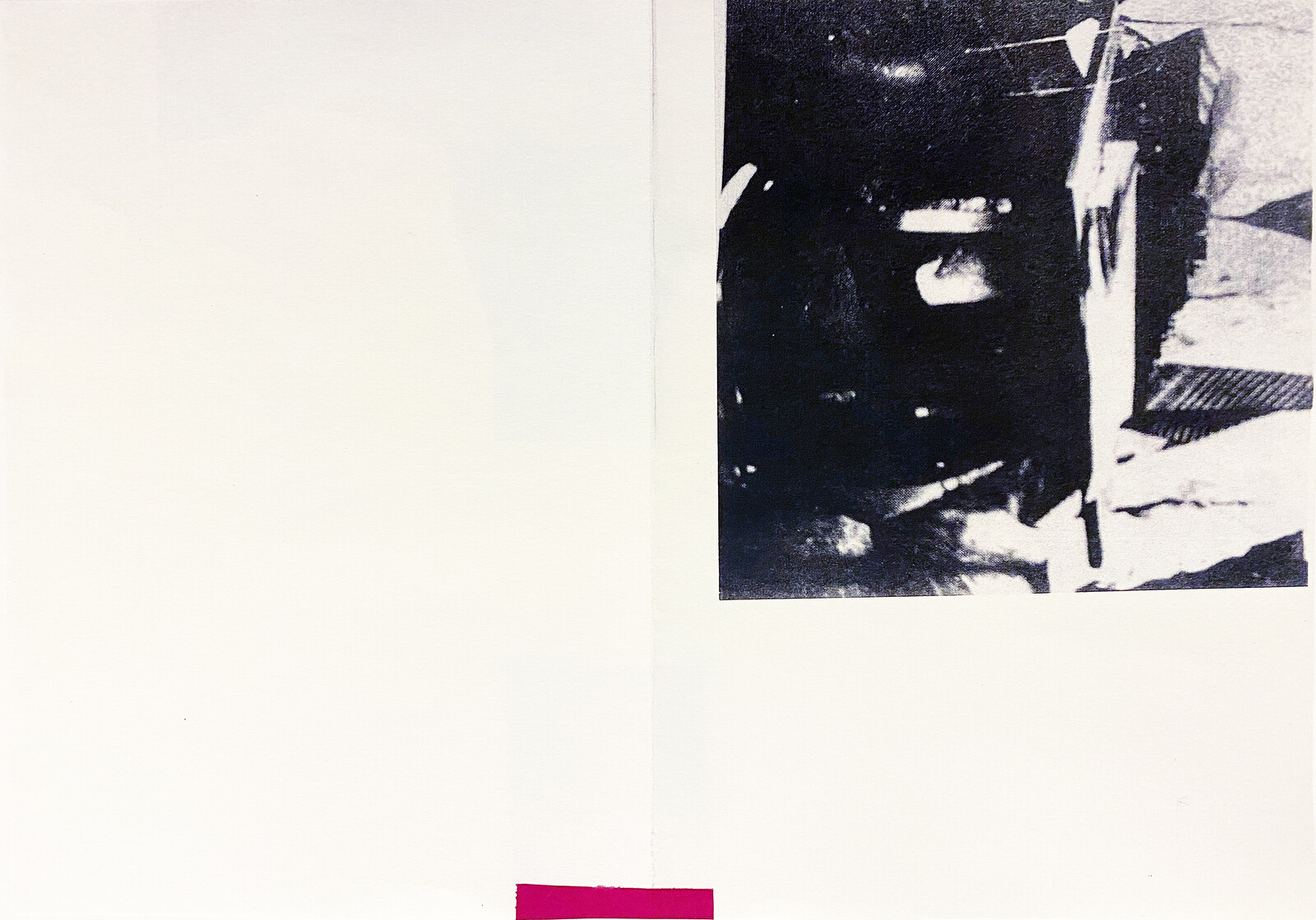

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 1 of 12.

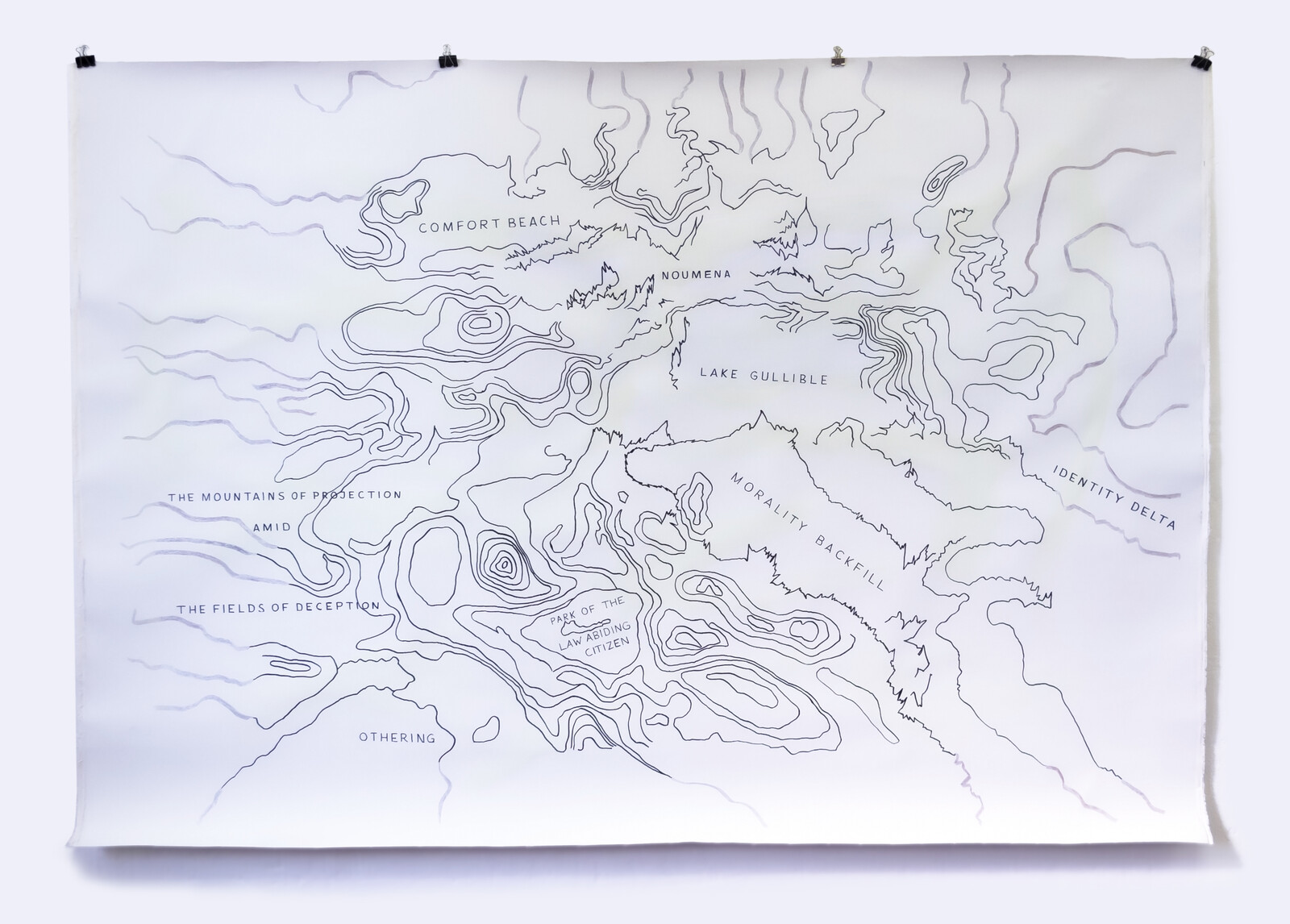

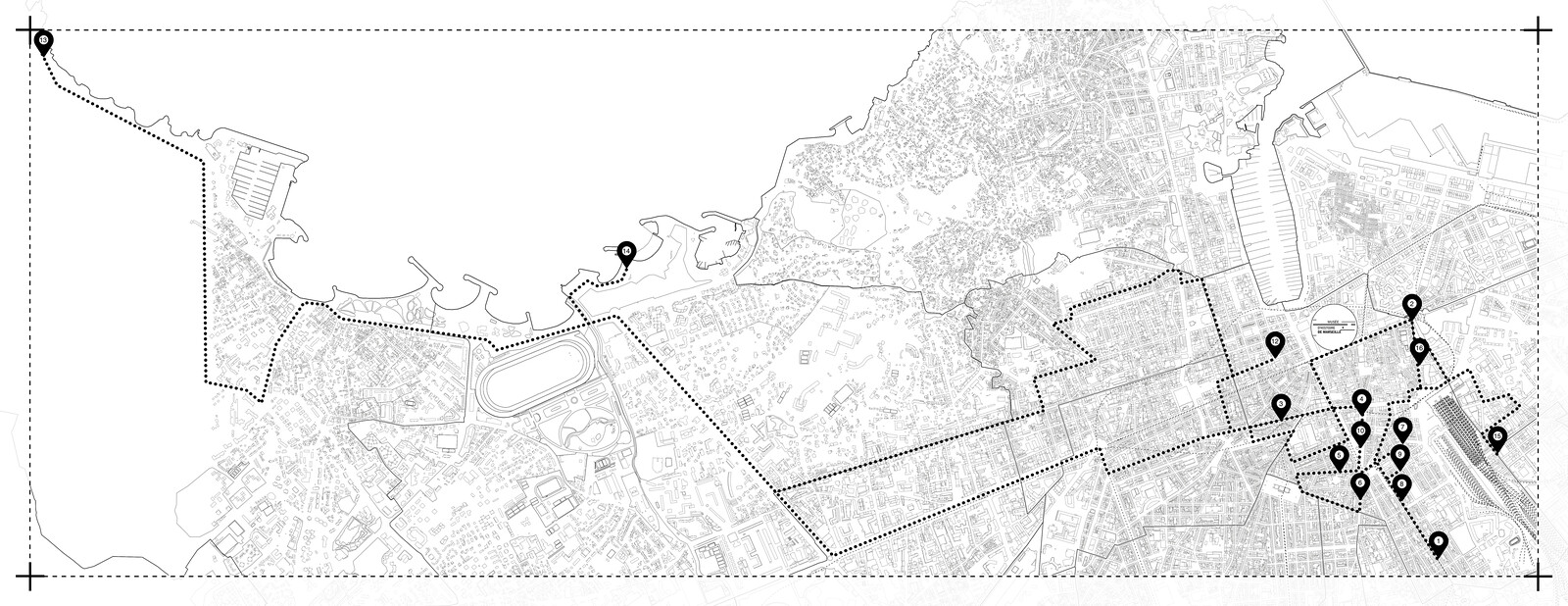

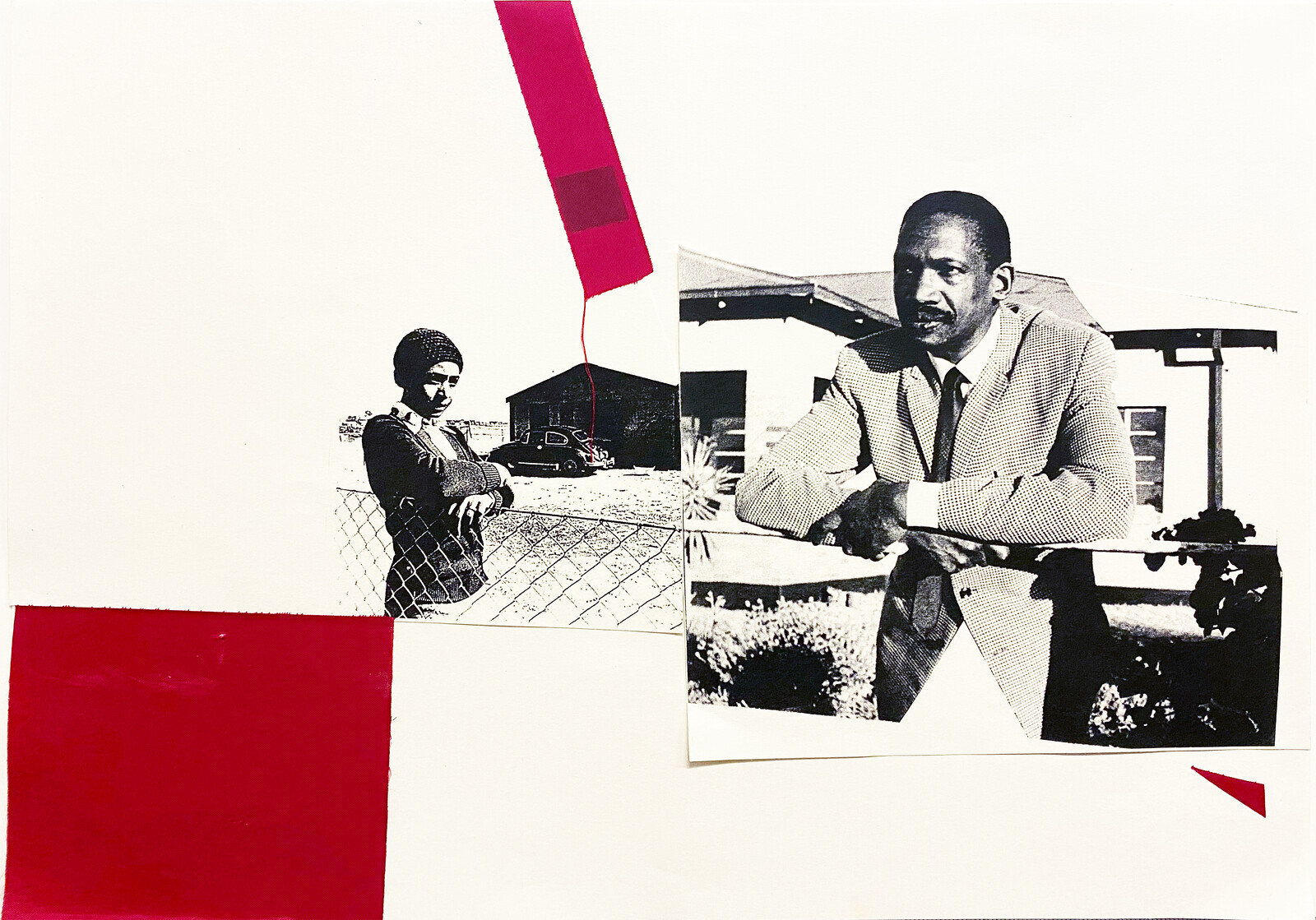

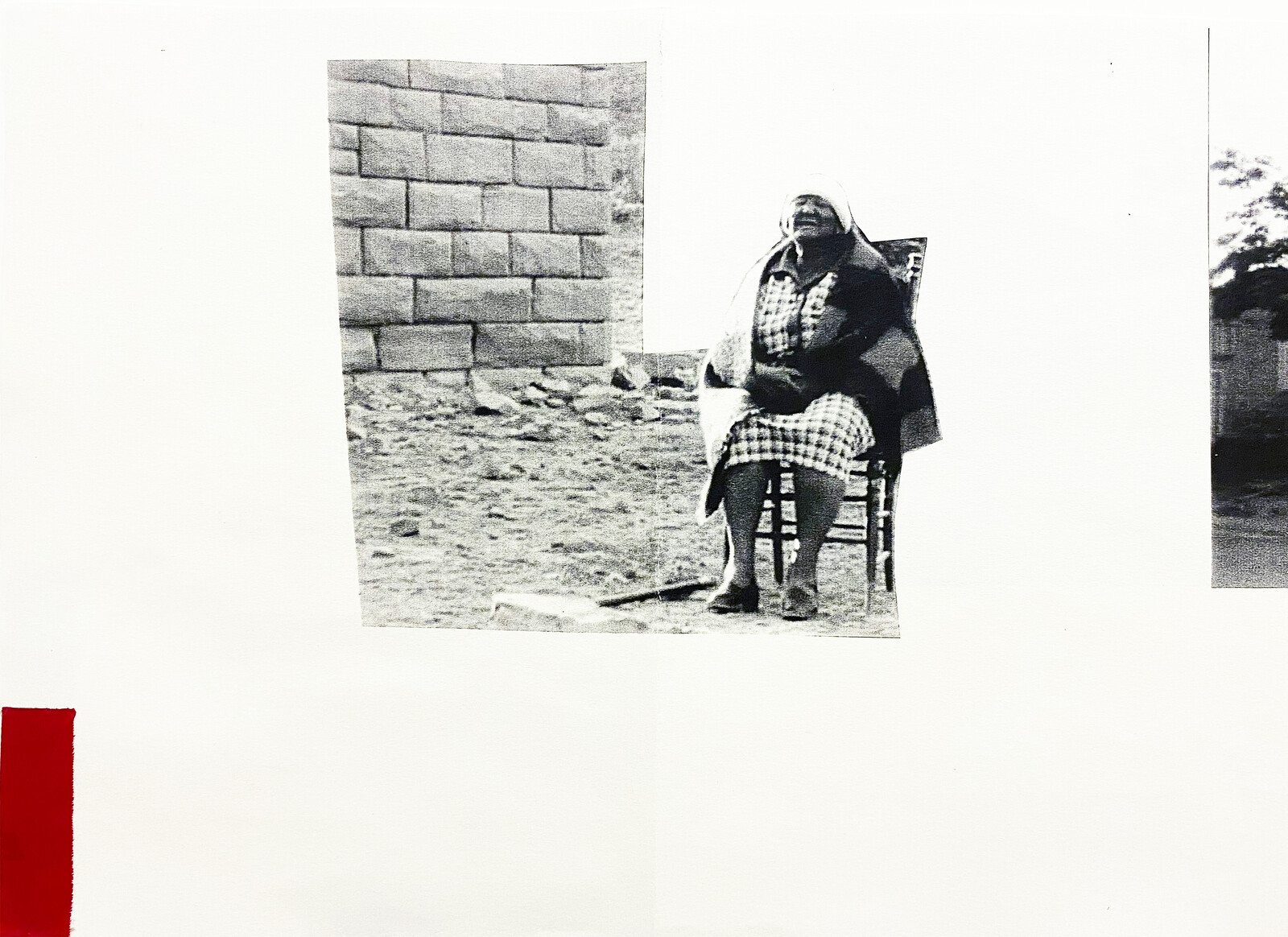

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 2 of 12.

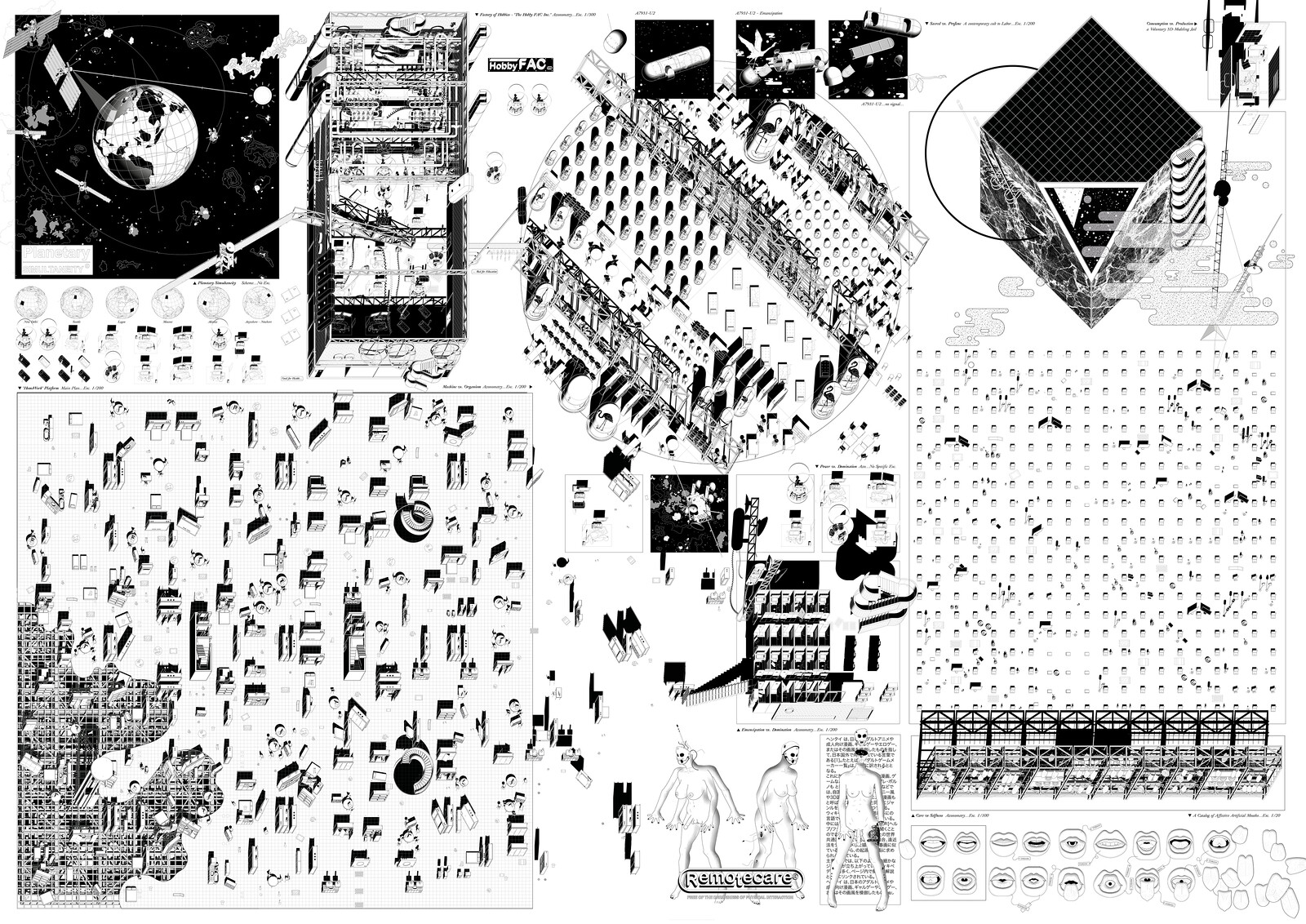

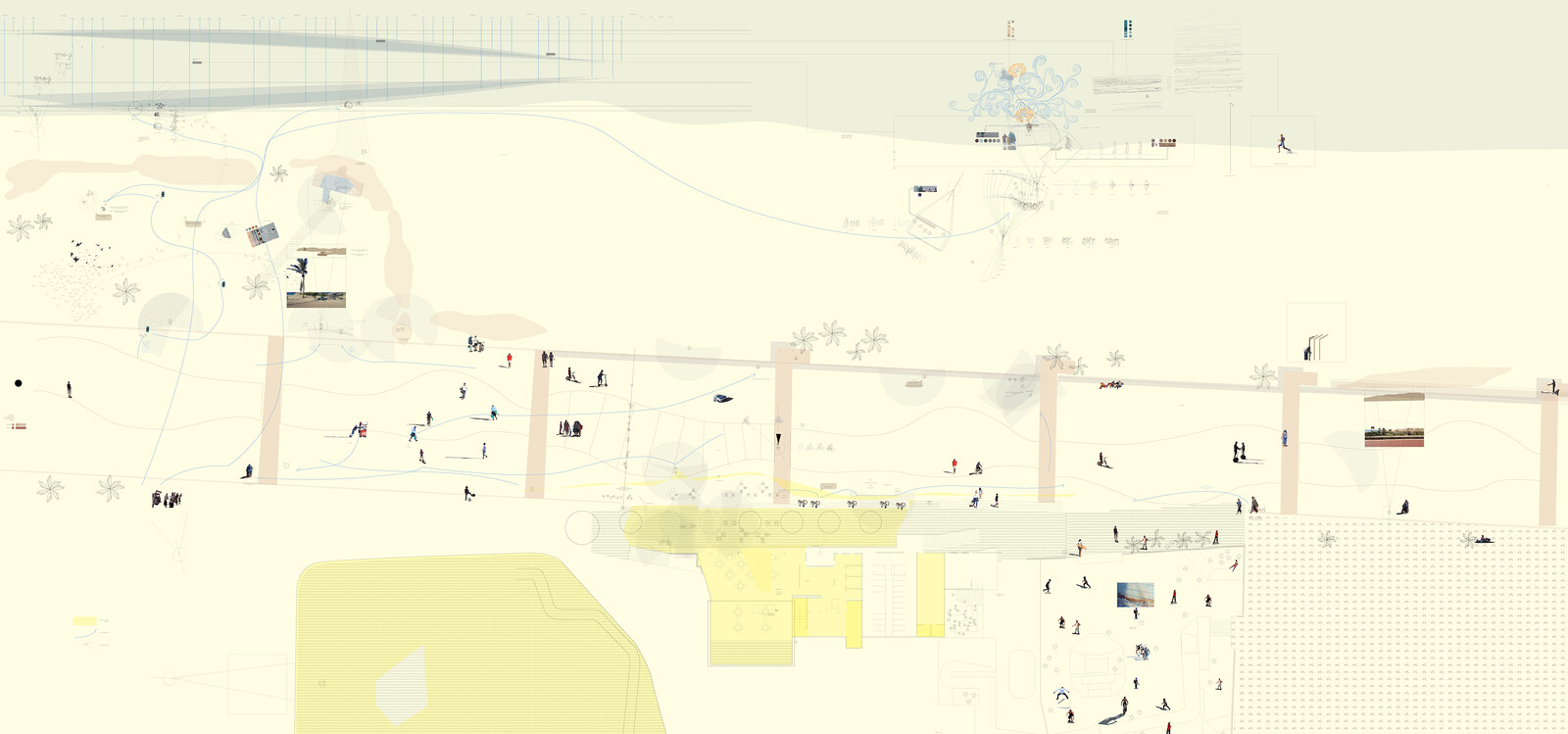

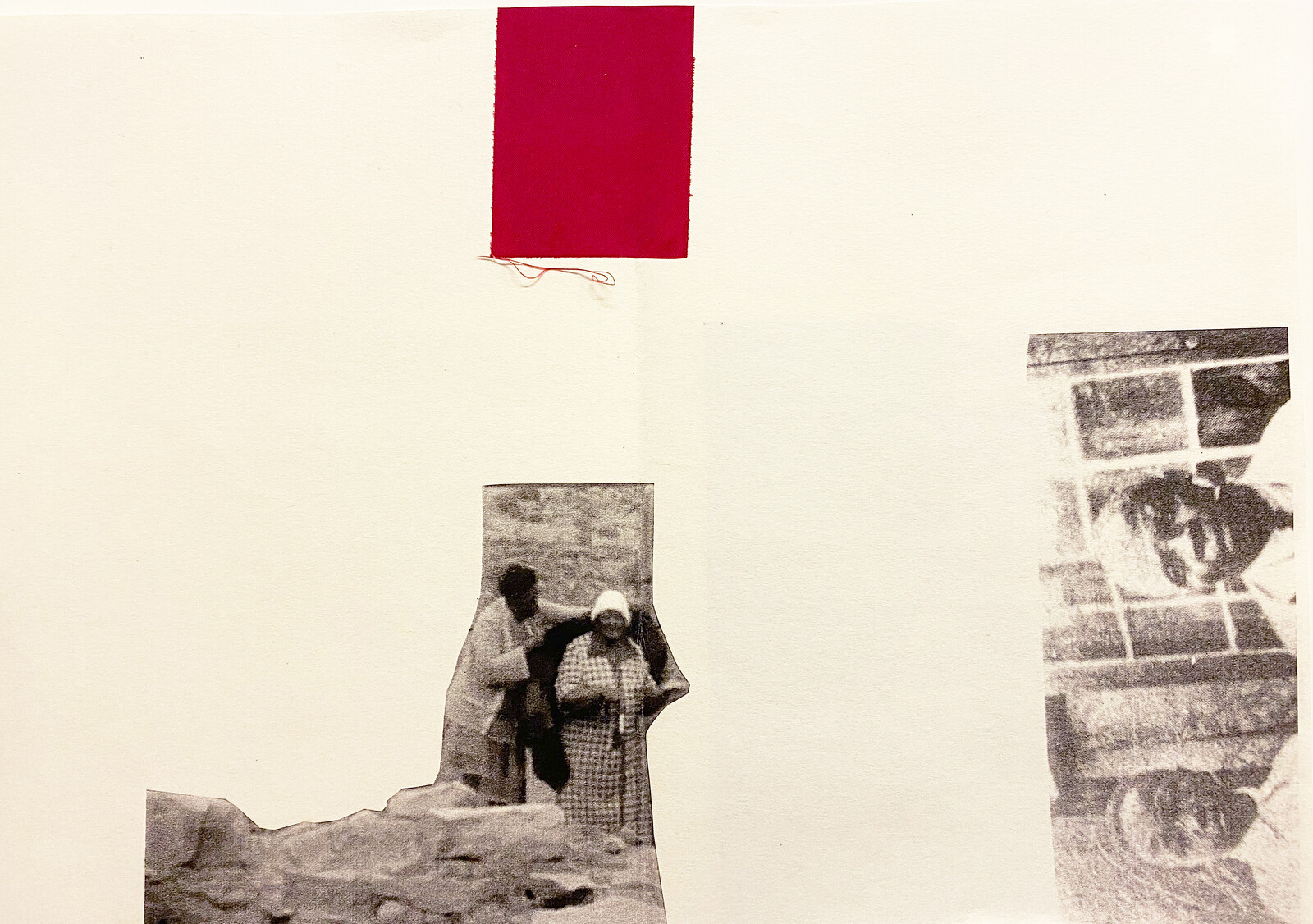

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 3 of 12.

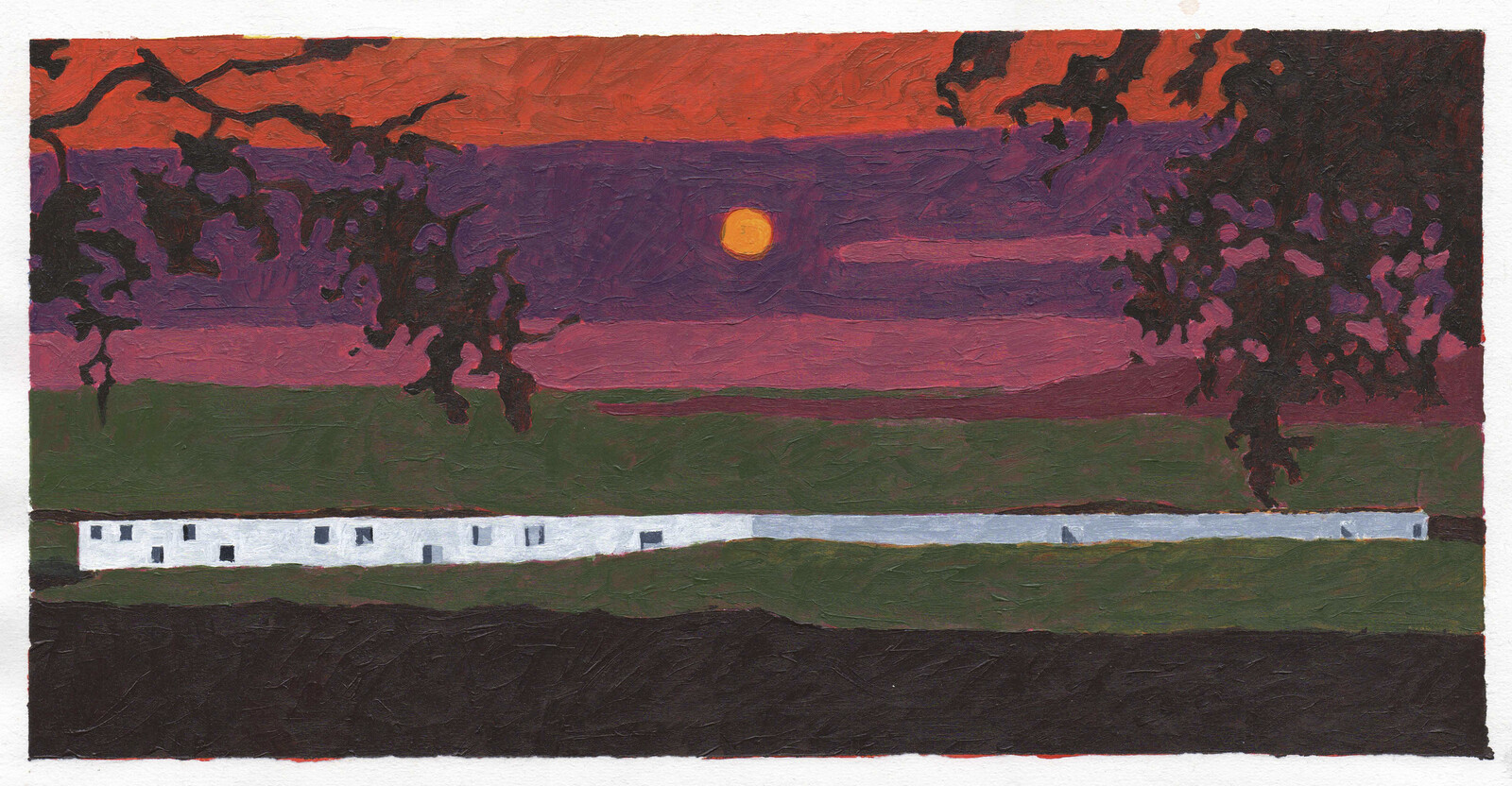

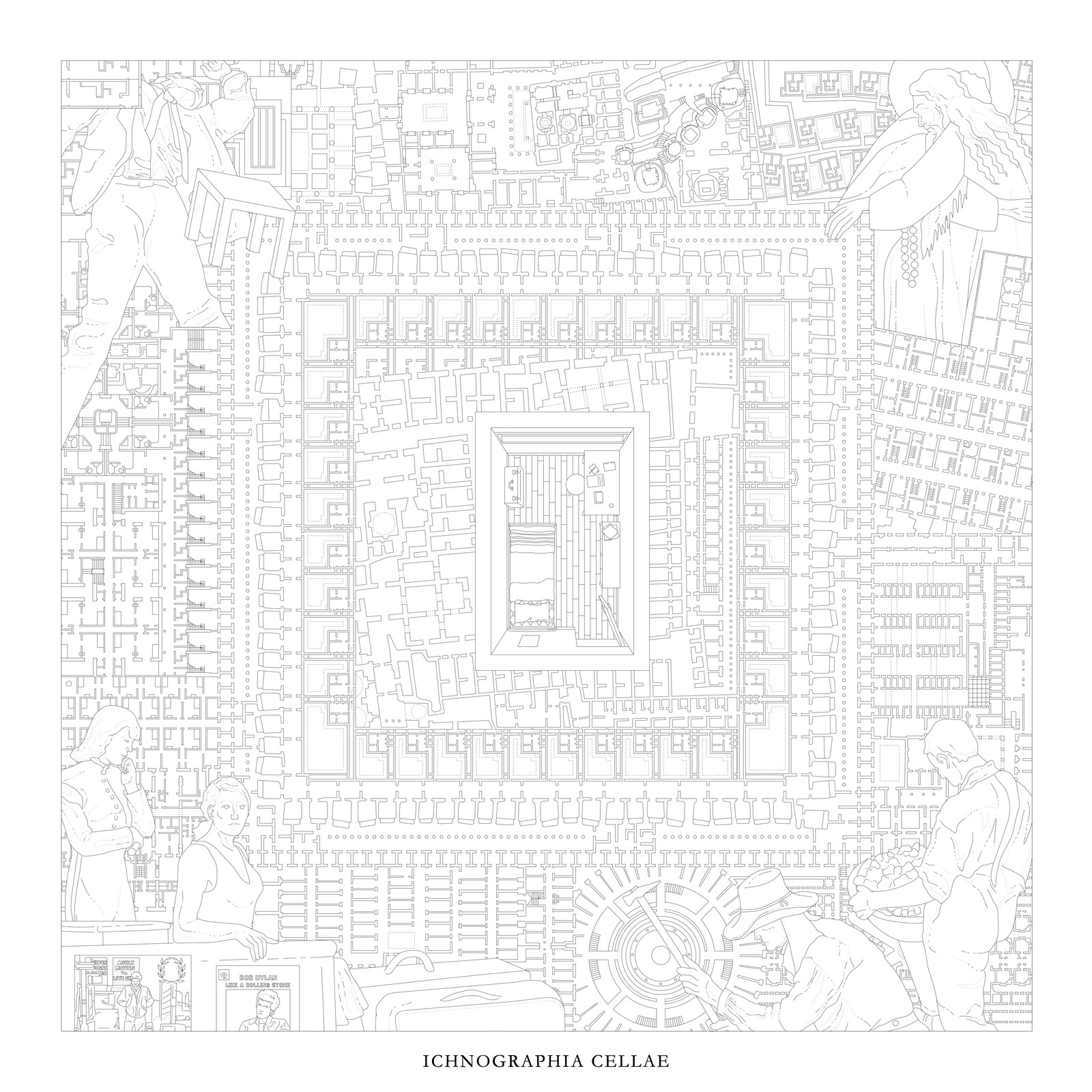

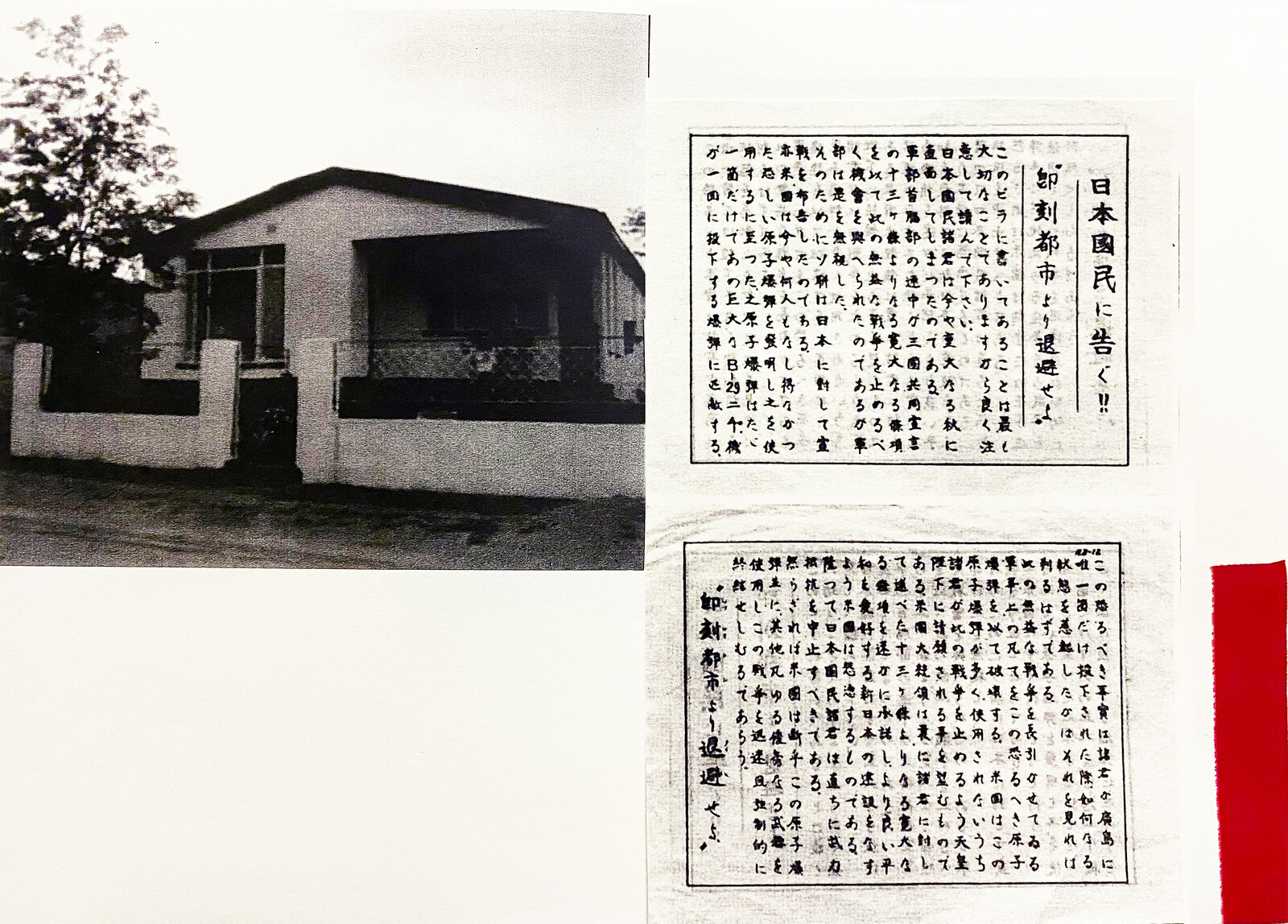

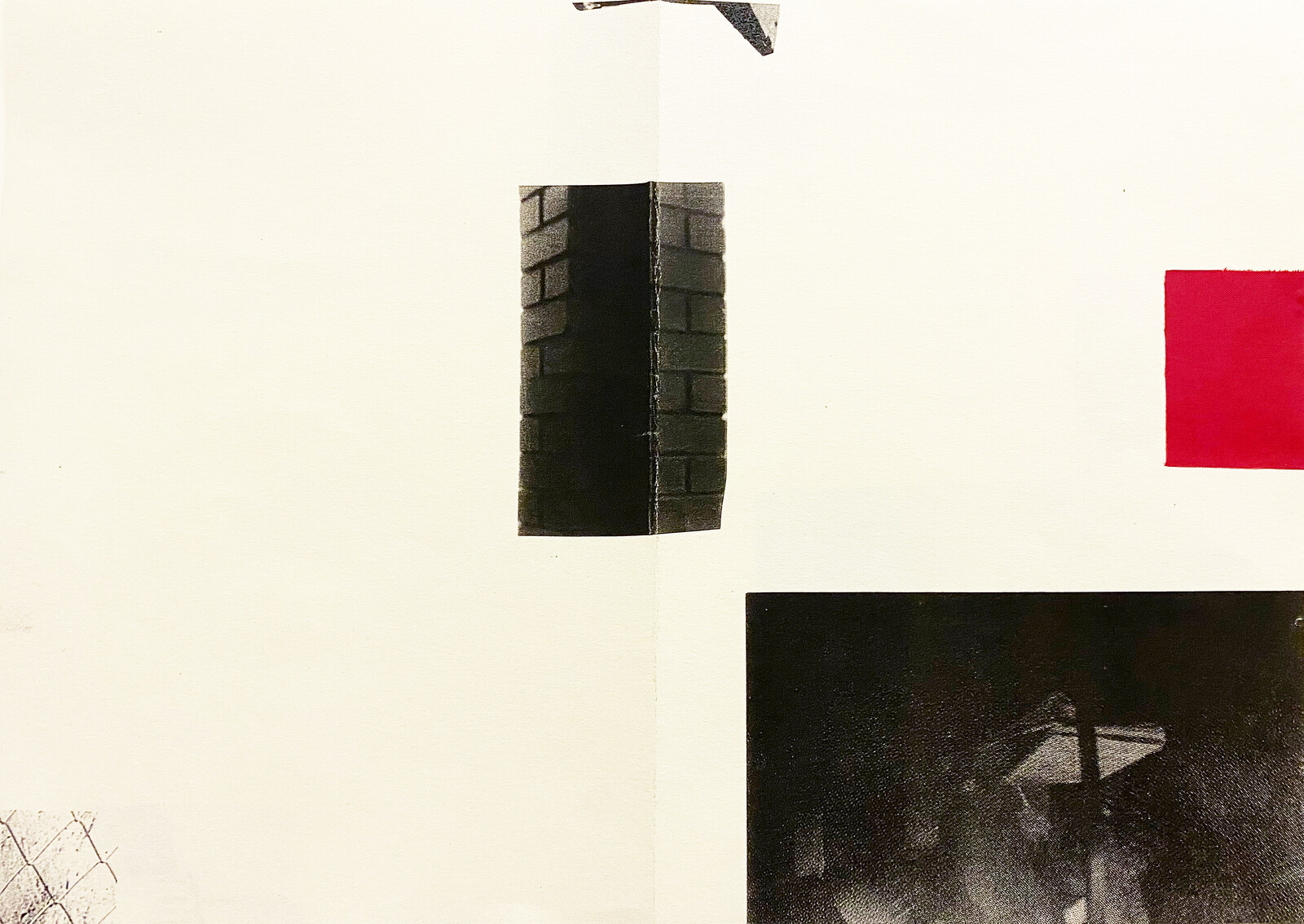

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 4 of 12.

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 5 of 12.

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 6 of 12.

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 7 of 12.

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 8 of 12.

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 9 of 12.

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 10 of 12.

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 11 of 12.

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 12 of 12.

Ilze Wolff, Black Peace on Earth, 2020, sheet 1 of 12.

August 09

To my friend, the poet,

Thank you for your words. I think you have captured in poetic form the landscape of emotion and thought that matches the visuals I have been sending you and the conversations we have been having. I have sent you wordless images and in return you offer your own poetry of images. In addition, may I expand our exchange with a few more thoughts and some more stories?

In an early poem called “My Home,” Bessie Head invites us into her home. She writes: “Come and see my home. It’s anyplace where nobody gives orders.” It is clearly an invitation, but she asks that anyone who accepts the invitation should take a certain responsibility. She asks: “Tread softly—the walls breathe peace… Deep, dark, black peace and the wind don’t blow.”

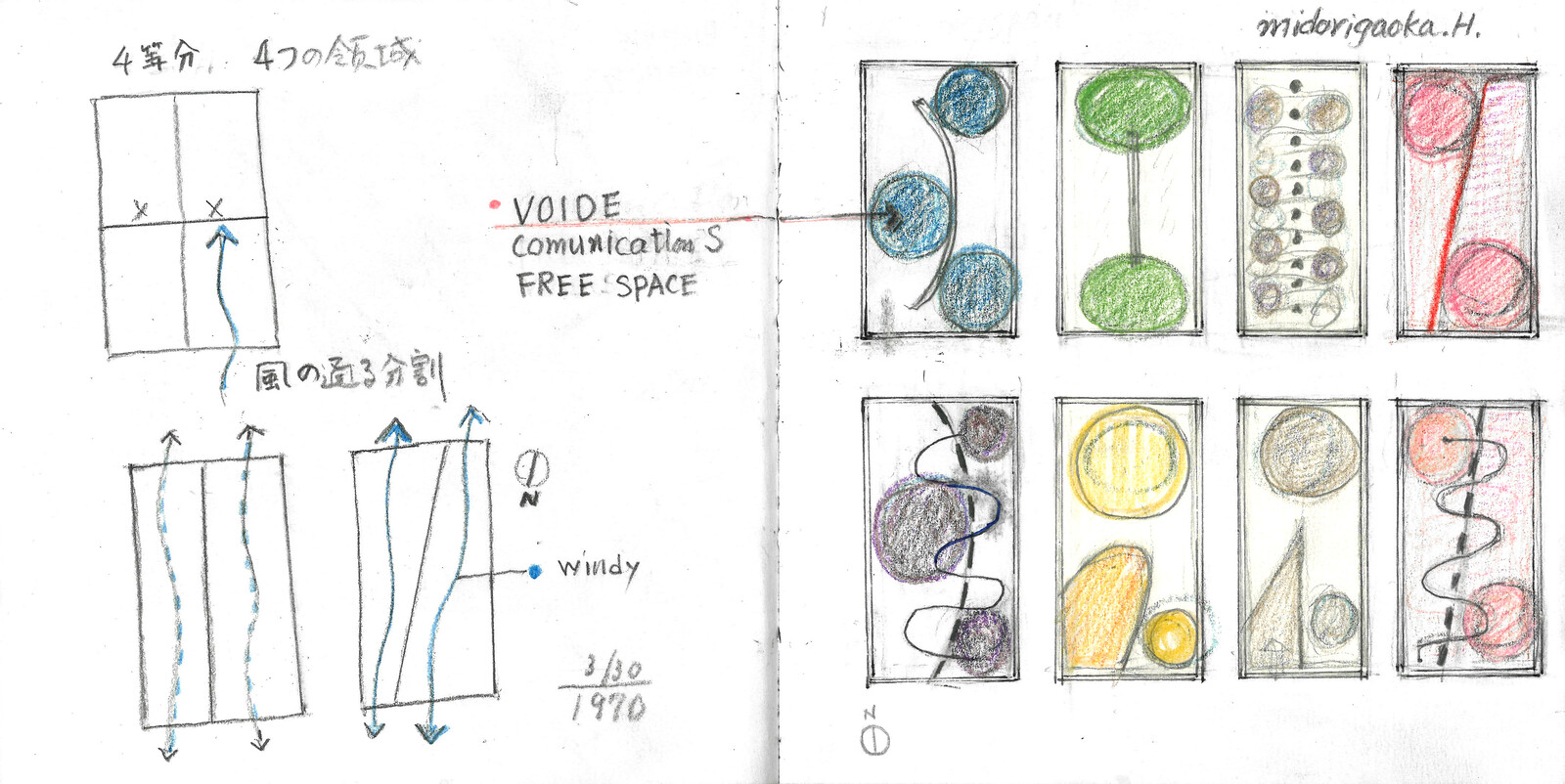

One could imagine that at the time that she wrote this—the early 1960s—John Coltrane heard her voice from Serowe, all the way in New York, where he was composing music like Alabama and A Love Supreme. In 1966, the John Coltrane Quartet toured Japan, twenty-odd years after the devastating atomic bomb attacks in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In Nagasaki, he opened their performance with Peace on Earth. It is a performance considered by many who attended the concert, or who heard about the performance, as a moment of collective healing. I think of this story and it makes me remember, as a child, the sensation of the breath of a beloved parent gently blowing on a wound that was just inflicted by accident while playing. I remember, the acknowledgement and care through the act of blowing is the soothing balm, rather than the application of the salve or even the administering of the bandage.

These two stories are linked: Coltrane blowing Peace on Earth in Nagasaki and Bessie Head’s careful invitation to come to her house and share in the experience of black peace that the house offers and I feel renewed.

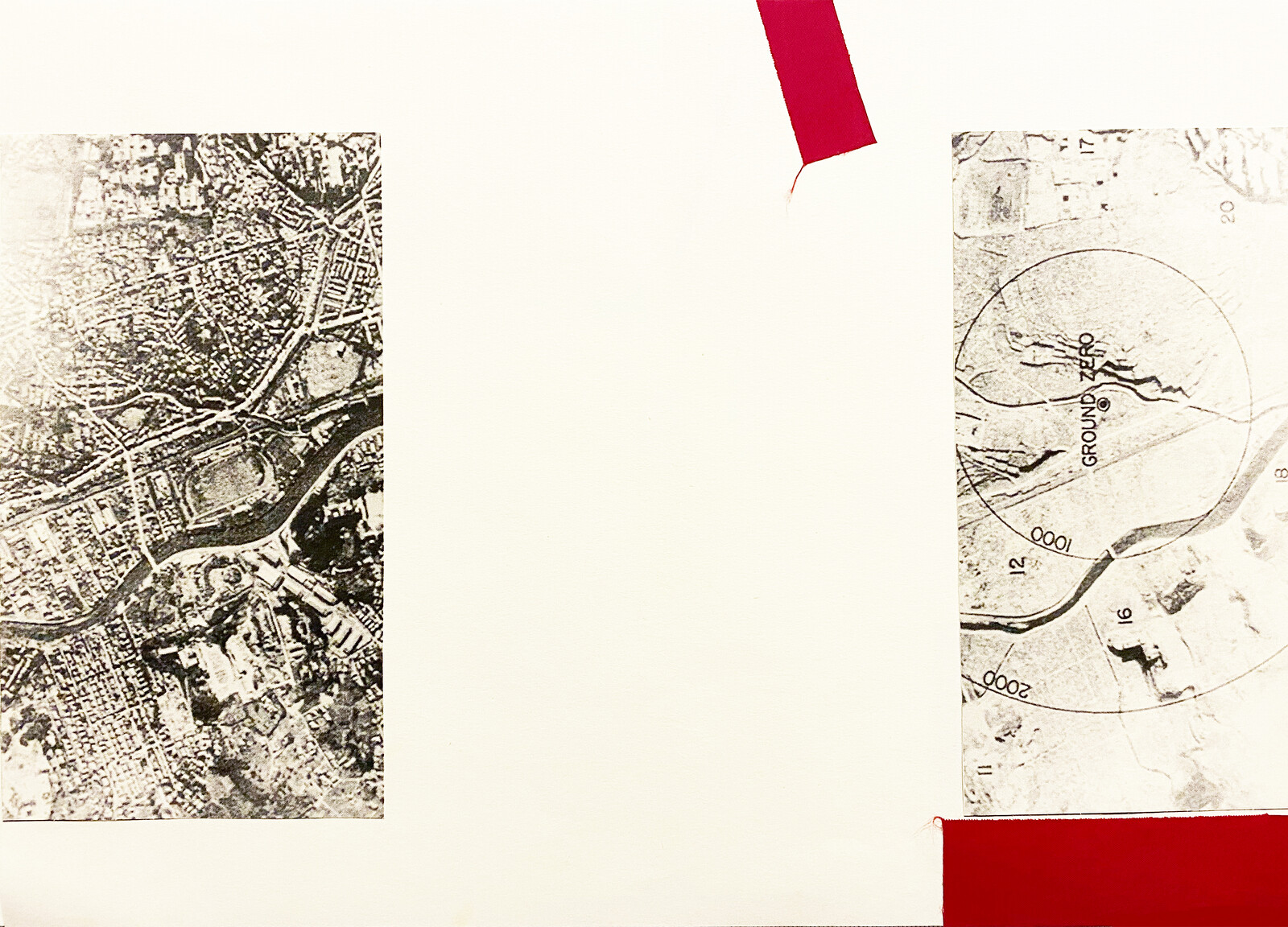

Incidentally, did you know that prior to the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings in 1945, the Allied forces dropped warning leaflets from aircrafts so that civilians could prepare for evacuation? The image of the atomic cloud is imprinted into our collective imagination, less so are images of falling leaflets with this important message pouring downward and blowing into and onto the city, some falling into the hands of the intended receivers, others blowing aimlessly in the street. It reminds me of what a friend once wrote regarding the power of the word. That the drop of the atomic bomb was given through Word. But here, another tension exists where the word, through these leaflets, is able to warn against impending death and destruction. The same technology that is behind issuing death, is also there to warn about impending death.

Personally, I know too little about this history to know if such footage exists, but I was able to track down an image of one such leaflet on Wikipedia for our conversation.

Also in the images I sent you, you will notice a pattern of people in front of their homes. Peter Magubane’s portrait of Winnie Madikezela-Mandela in front of her house to which she was banished to by the apartheid police is iconic, and one can have long conversations just about that picture. Then there are also the ones of Robert Sobukwe in his house to which he was confined to for nine years on Robben island. He looks relaxed and joyful: a kind of composure that belies the indignity that he suffered by being in solitary confinement for so long.

But I also sent you some images of another figure in front of his house: the two of Sol Plaatje and his daughter Violet. Plaatje, in 1926, on his fiftieth birthday, received a house as a gift from his friends and loved ones. Two photographs exist of him in front of this house. In both images he is seated next to his daughter, Violet, and behind a writing desk and typewriter. However, there are two distinct differences in these two photos: in one he is wearing a hat but looking away from the camera, and in the other, he is looking straight at the camera, with no hat, but with a pipe. In both cases, Violet holds the same pose, which is a slight side profile and looking at the camera. Behind them we see the windows and perhaps the entrance to the house. These images are in two separate biographies on Plaatje—one by Brian Willan the other by Seetsele Modiri Molema. Willan chose the hat photograph and Molema chose the pipe. To me, both images seem like drafts of the other, in preparation of a final pose and testing various stances. I would be keen to see a final portrait if such a thing exists.

The screenshots of the film included in my earlier email to you is of the 1984 film Tsiamelo: A Place of Goodness. I am sending you the YouTube link as I write—please have a look if you have not done so yet. The film is narrated by Ellen Kuzwayo, who herself is an important figure in our history, but in this film we learn a little more about Plaatje. Ellen takes us to his hometown where we meet some of the people that knew him. It opens with a song and her walking the streets of London, retracing the steps Plaatje took during the publication of Native Life in South Africa, the famous book about the 1913 Land Act.

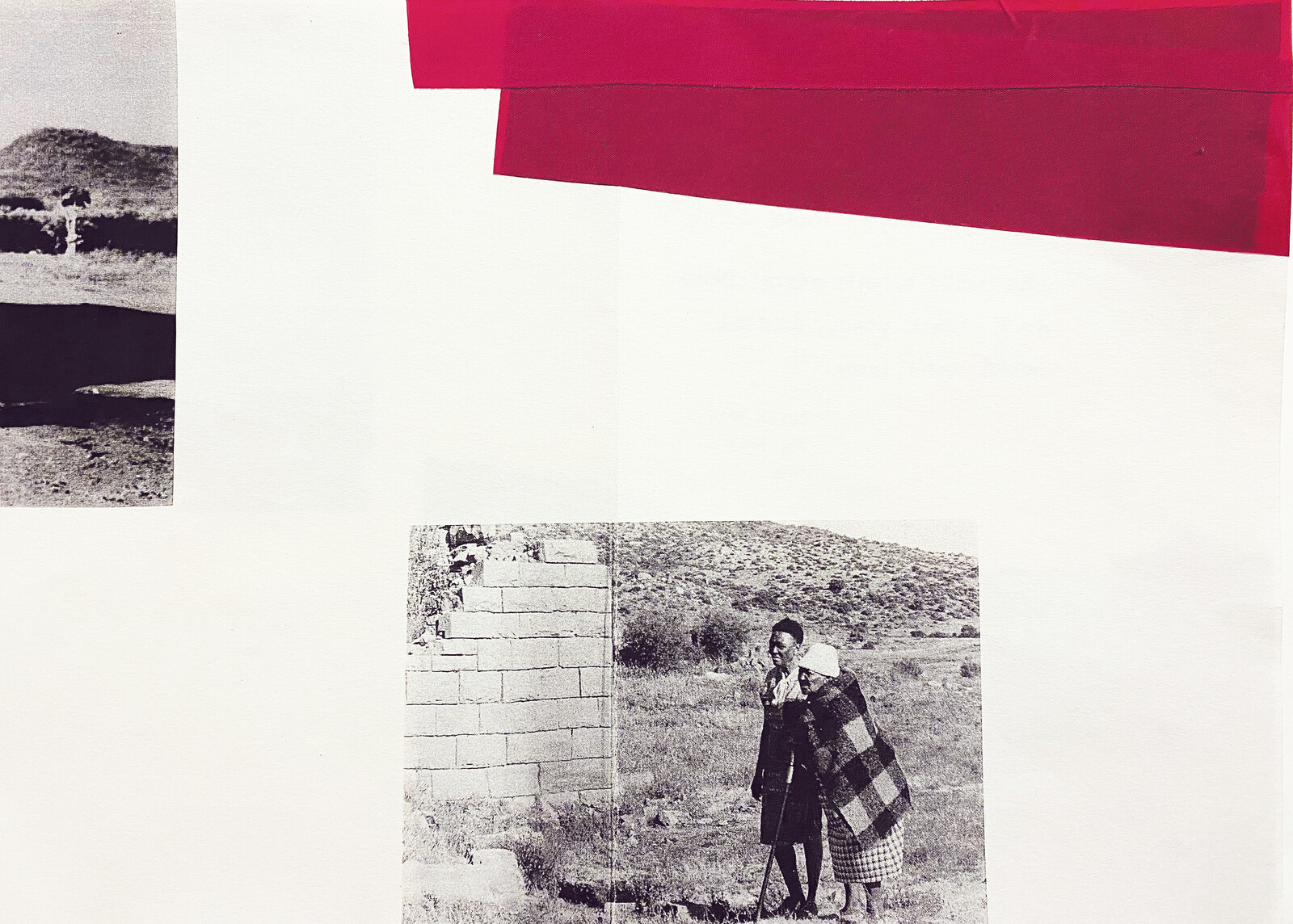

Please have a look at this film if you have time? It is not the easiest film to watch. Aesthetically, it is not creative, yet as an archival object it is highly informative of some important moments in our spatial history. I was particularly moved but the exchange between Ellen Kuzwayo and Blanche Tsimatsima. In that scene, we sit in on a conversation where Blanche describes how she was able to inherit a large farm from her deceased brother. The transfer of property is not without obstacles for Blanche. She finds out that as a woman, she is not allowed to inherit land, yet as the only surviving descendent she was entitled to this land and she fights for her right to the property. She says that she simply put on a pair of trousers, went to the deed’s office, and demanded her inheritance! Of course, we learn later in the film that in 1974 her farm is declared a “black spot” by the apartheid government and she and her family is moved off the farm that she cultivated throughout her life.

In one image, Ellen and Blanche are captured on the threshold of what is the ruins of her homestead. This scene powerfully depicts the hardship so many black families suffered because of the 1960s and 1970s’ forced removals and the consequences of the 1913 Land Act. I am so happy I found this film, this visual document. As you will see, I think that I am particularly drawn to the way in which the story is told: by way of walking in and amongst the ruins, recalling the space from memory, and then the meditation offered for the future. At one point, Ellen puts a blanket over Blanche. The camera pans out and we see more of the remnants of the stone house. The act of shrouding Blanche with this blanket is a beautiful way of enclosing her and this terrible history with a sense of meditation and homage.

So, yes: these images I sent, the words, your poem which we have called “Black Peace on Earth,” is a broad capture of many connections that we both saw in the patterns of forced removal, destruction of homes, and also the act homage.

I thank you for joining me on this. With much appreciation.

Ilze

Confinement is a collaborative exhibition curated by gta exhibitions and e-flux Architecture, supported by the Adrian Weiss Stiftung and the ETH Zürich Foundation.