Over the past twelve months, two international initiatives have been closely watched because they appear to set the terms for a new, globally punishable, architectural criminality. The Italian-Jordanian initiative Protecting Cultural Heritage: An imperative for humanity mobilized the UN, Interpol, and UNESCO to stem the looting and smuggling of antiquities out of war-torn Syria by demonstrating that their traffic “finances terrorism” and is “linked to international crime.”1 At the same time, the International Criminal Court of the Hague tried and indicted Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, a Malian citizen who orchestrated the destruction of ten mausoleums and mosques in Timbuktu on behalf of Ansar Dine (an affiliate of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Magrheb, AQIM) in the broadest-ever judicial ruling that architectural destruction is punishable as a war crime.2

These two projects promise to bridge two notions, “heritage” and “humanity,” that have been separated in international law for at least a hundred years.3 Legally, the bifurcation can be traced to the aftermath of World War II. Since the 1954 Hague Convention, heritage laws have protected architecture as a kind of collective property, whereas texts such as the 1948 Human Rights Declaration codified humanity as an attribute of individual personhood. Any reference to cultural heritage was deliberately excluded from the 1948 Genocide Convention, signed that same year.

But historically, the split predates these laws. World War I was the first conflict where modern nation-states competed and collaborated to protect their art and architecture. In fact, these protective measures were so well-publicized that after 1918 Europe’s cultural elite became consumed with debates about whether armies had been more concerned with their art than with their citizens. Fearing that humans and things might have to compete for protection in future wars, international lawyers found themselves split for much of the twentieth century in an apparent opposition: advocate either for culture or for human rights.4

Video stills of prosecutor Fatou Bensouda and accused Mohammad Al Mahdi during the trial.

Fast-forward to September 2016. The ICC’s judgment against Al Mahdi explicitly seeks to move past this split legacy. “Crimes against property are generally of less gravity than crimes against persons,” states the ICC Chamber, but this particular attack was “heightened by the fact that it was relayed in the media”—that is, it was amplified by its consequences for the international community.5

So if protecting heritage has become an “imperative for humanity,” it is by undermining the early-modern and Enlightenment definition of the human as distinct both from things that are less than human (such as barbarians, animals, or inanimate objects) and also those that are more than human (such as gods).6 At the ICC trial, the religious aspects of destruction took a notable back seat, while its technical and material logistics, and the nature of Timbuktu’s mosques and mausoleums as “living” heritage, were emphasized.

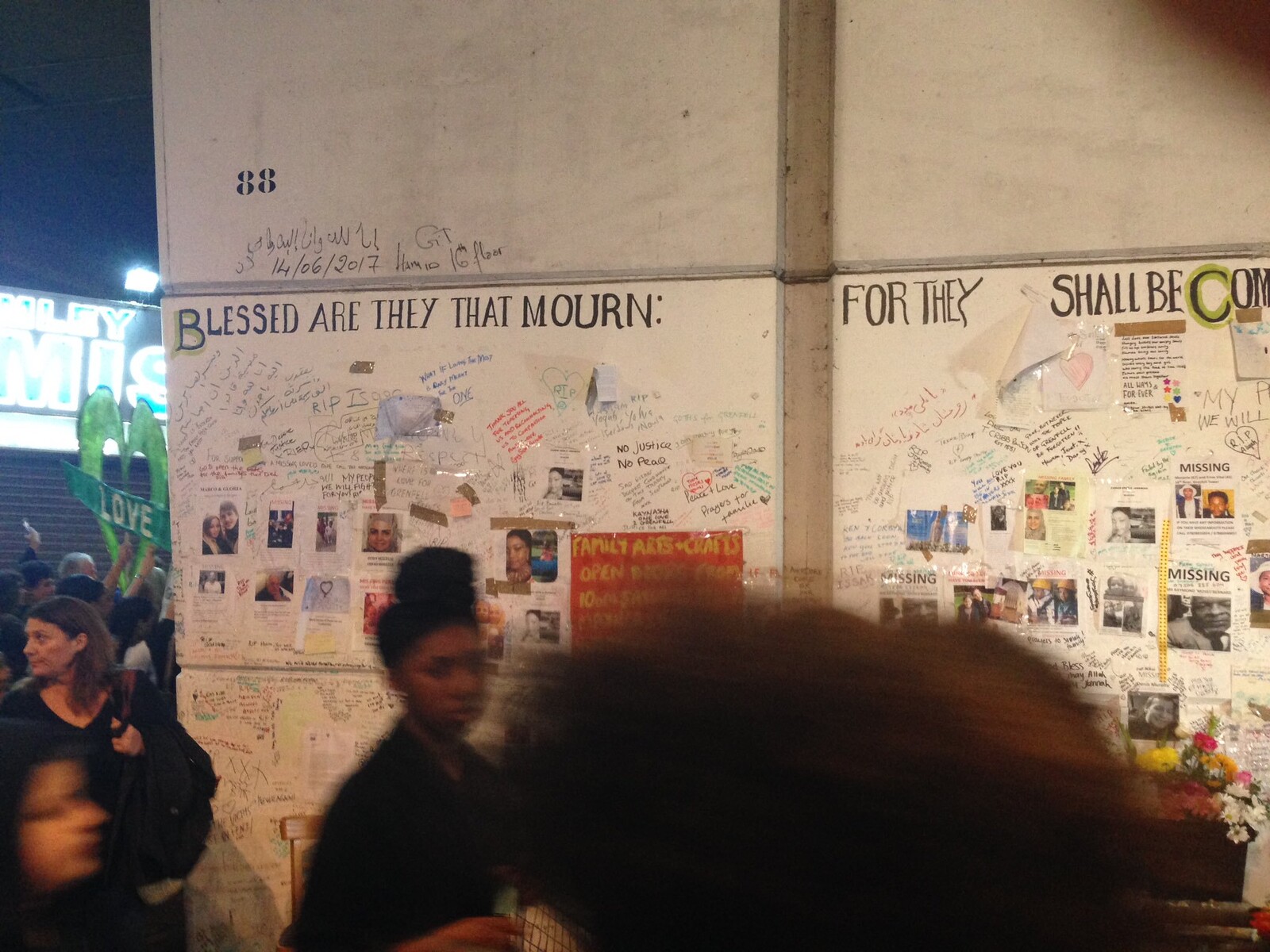

To be sure, tensions lie just beneath the surface of the apparent consensus that the Al Mahdi case is ground-breaking. Critics point out that Al Mahdi’s confession and cooperation with the court means that the case sets no new evidentiary standards.7 Human rights advocates worry that a victory in punishing violence against buildings might obscure crimes against persons, including the widespread sexual violence committed by the very same group, during the very same period and in the same urban spaces of Timbuktu. The Malian association for Human Rights and Amnesty International have both called for “an expansion of the charges” against Al Mahdi.8 The stakes of punishing architectural destruction are therefore clear: is it a proxy for exposing more pervasive but more invisible human rights abuses, ones whose victims are chosen for their collective identity but targeted as individuals, living in a city under siege.

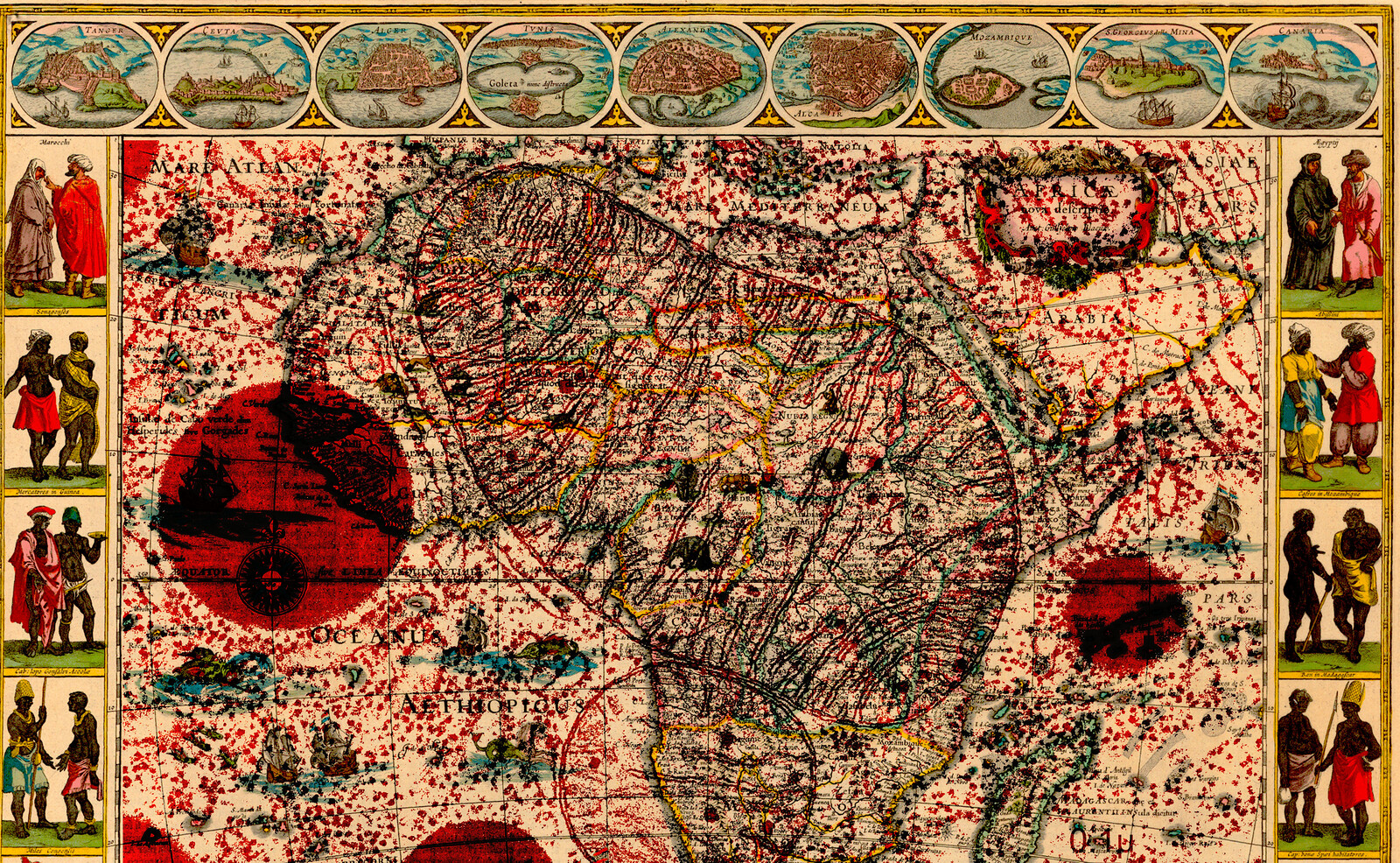

René Caillié, View of the City of Timbuctoo From English Translation of René Caillé, Voyage à Tombouctoo. Translated as Travels Through Central Africa to Timbuctoo, and Across the Great Desert, to Morocco, Performed in the Years 1824-1828. 2 vols. London, 1830. Gift of C. W. McAlpin, Class of 1888. [Rare Books Division]

If the relationship between heritage and humanity has been reconfigured from an opposition to one of proximity, what are the architectural terms of this proximity? What are the operations through which the “expansion,” or “widening” of crime and punishment alike are imagined? In this essay I probe these questions in two parts. First, the accused’s discourse, in court and in abundant video evidence, provides an entry point into the logic of sincerity that motivated the design of the destruction of Timbuktu. Second, an analysis of the practices that authenticate Timbuktu as an international treasure—both in court and in ongoing preservation—reveal the techniques of amplification that are embedded into the built environment to hold together an agreement, on both sides of the law, that the target of this new criminality is humanity itself.

Philippe Desmazes, Photograph of the Minaret of the Great Mosque in Timbujtu, date unknown. Detail. Photo: Getty Images.

Life on the Architectural Surface

Heritage and humanity are becoming proximate notions under the sign of a dialogue, or negative mirroring, between the ideologies of Western humanitarianism and global jihad. In his remarkable book The Terrorist in Search of Humanity, historian Faisal Devji shows the confounding parallels between the structure and functioning of these two movements: both operate through widely distributed networks whose end-game is non-governmental, who claim to occupy a privileged place of morality, and who recruit young and idealistic individuals “in search of humanity.”9

Devji’s work is informed by Hannah Arendt’s 1957 definition of humanity as produced through “negative solidarity, based on the fear or global destruction.”10 Arendt proclaimed that humanity had “become an urgent reality,” but one realized only in the face of the possibility for total extinction. Devji argues that something resembling this negative solidarity animates the suicide bombers of Al Qaeda for whom the “globe” (al-alam) can be unified only at the moment when it is left behind. To be sure, there is a difference in the two sides of Devji’s comparison: the search for empathy leads humanitarian workers to seek out sites of bare life, whereas the jihadist’s path culminates in sacrificial suicide. But two of Devji’s lessons are clear: first, assuming that Western humanitarianism is modern and secular while the Islamic militant project is fundamentalist and anti-modern only obscures the analysis of both, and second, destruction plays a crucial role in humanity’s coalescence.

Because Devji relies on Arendt, he already offers us a way of thinking of humanity and heritage laws as historically proximate. If a new humanity coalesced in the face of mid-century mass-murder, so too was the notion of international heritage worked out in response to massive scenarios of destruction during the tumultuous decades before its codification in the 1972 World Heritage Convention.11

Furthermore, Devji has updated his analysis to encompass the rise of the Islamic State, describing how, against the commonly assumed rift between modern superficiality and traditionalist depth, IS recruits are asked to live what he calls “a life on the surface.”12 “Efforts to explain terrorism tend to be structured as efforts to plumb the movement’s depth,” he writes, but in fact most recruits obey “banal forms of reasoning” that explicitly mirror the actions of the West, to expose its insincerity. Thus “it is not the content of the West’s actions that is put in question” by militant rhetoric, “but simply its hypocrisy.”

Devji invites us to read destruction looking for the “logic of equivalence that marks militancy.” For Al Qaeda, he cites Vyjayanthi Rao’s reading of the Mumbai bombing as an infrastructural counterpart to the smart bombs of the West.13 For ISIS, he diagnoses a “hatred of all historical, sociological and ideological depth” as motivating the architectural destruction “of pre-Islamic monuments, [and] also of all ‘traditional,’ ‘heretical’ or ‘infidel’ sites.”14

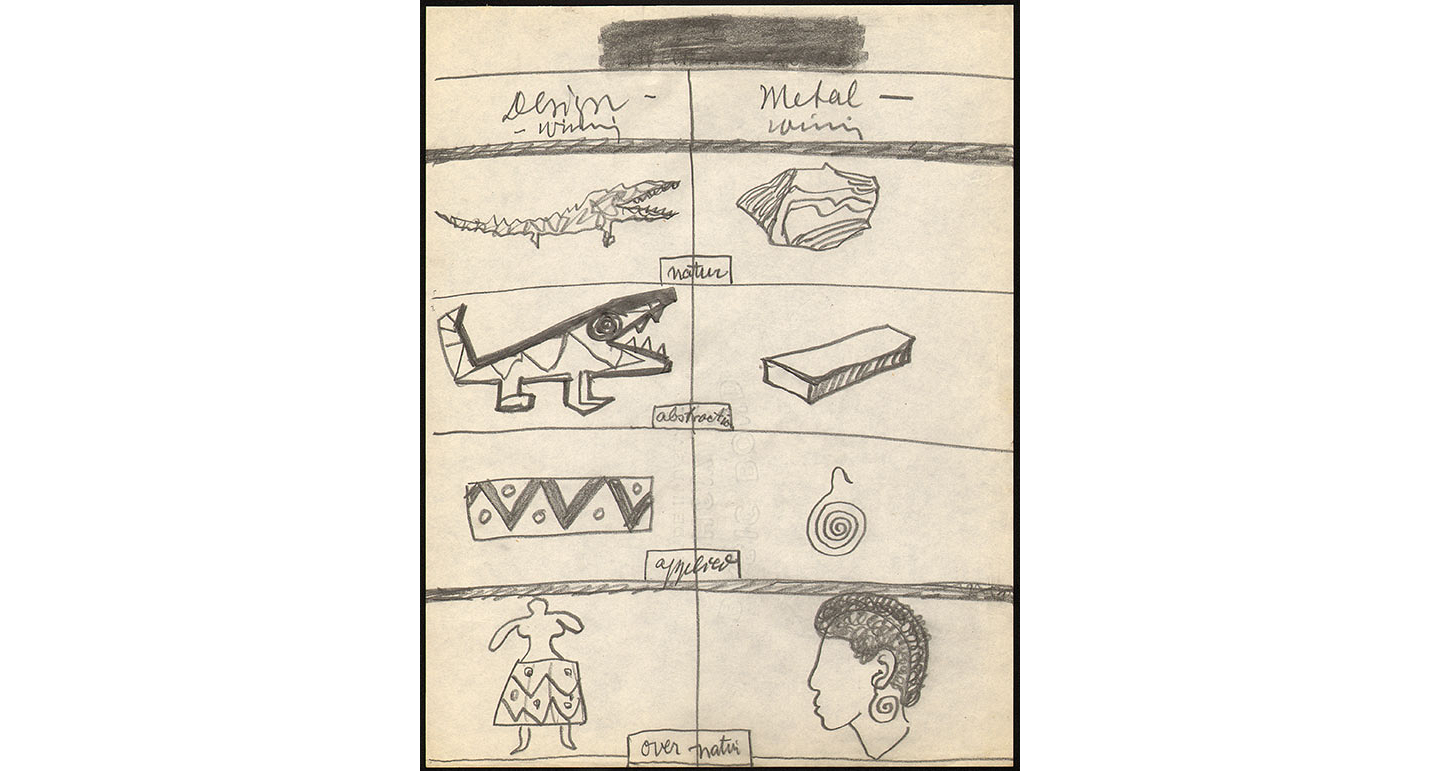

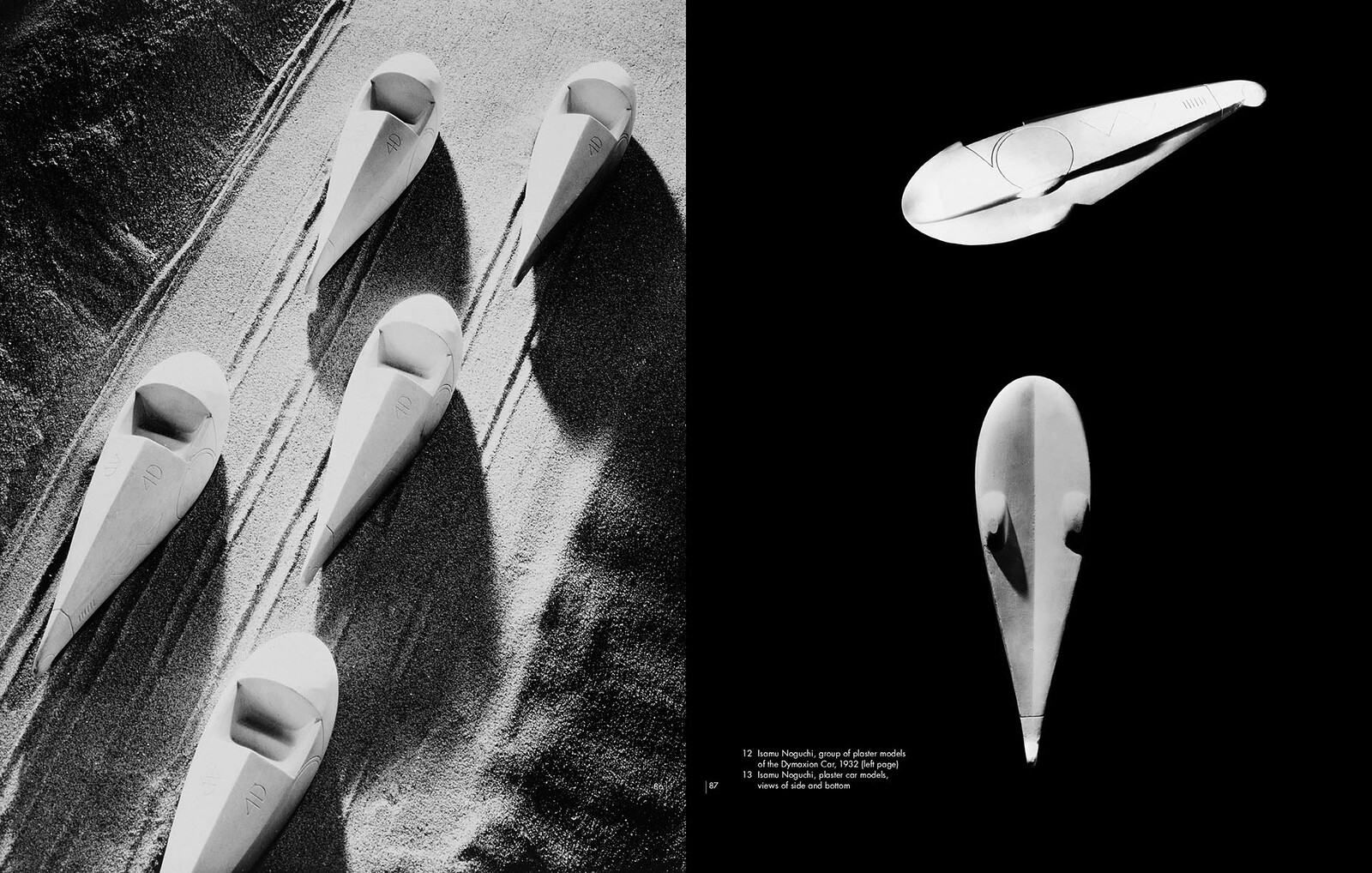

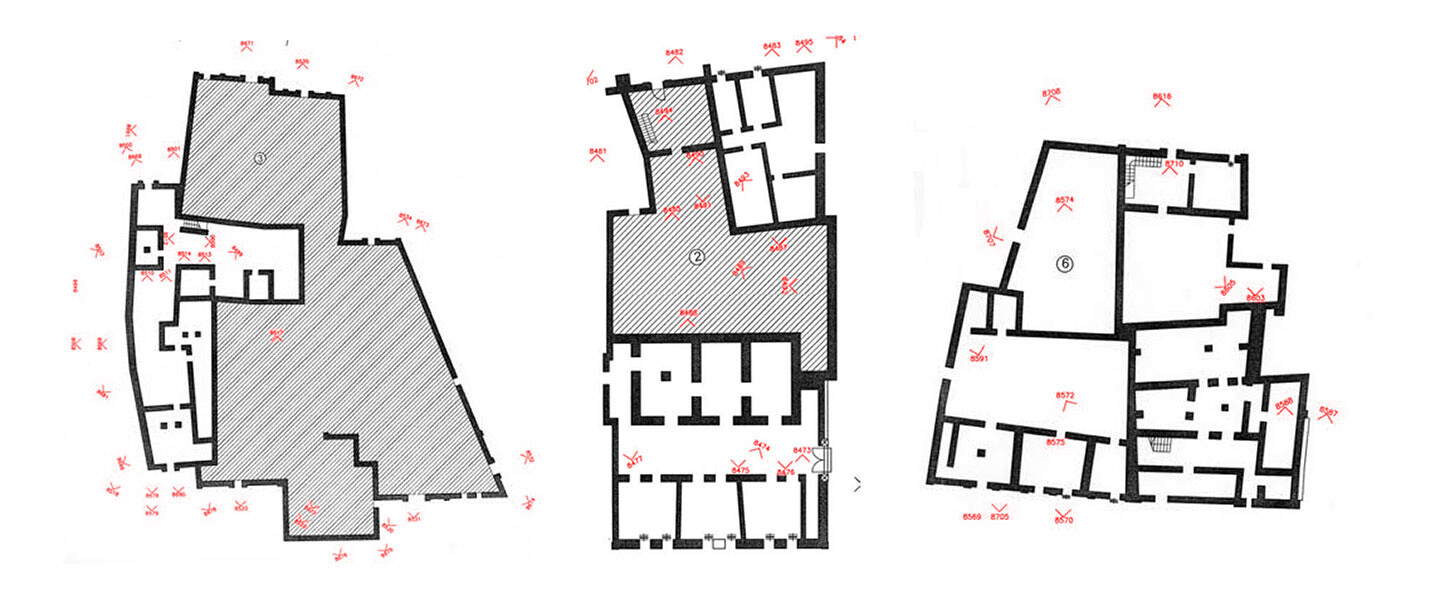

“Relevé de typologies dans le quartier de Sankoré” [Survey of typologies in the Sankoré quarters], published on page 40 of Unesco, Manuel pour la conservation de tombouctou (Unesco: 2014).

Returning to the case of Timbuktu, then, we find destruction that both echoes Al Qaeda’s concerns for global belonging, and constitutes an early example—an experiment, really—of the attacks on funerary structures that the Islamic State would later make systematic, beginning with the invasion of Mosul.15 In Timbuktu, Al Mahdi leveraged both the infrastructural, networked nature of the city, and its nature as a historical root. Additionally, I would like to argue, the attack on the mausoleums and mosques was motivated by an almost superficial reflectivity, a ghostly mirror of the profundity that is assumed to be granted by the West to these locally-revered objects.16

Consider, first, the carefully-timed game of retaliation that motivated the destruction. Ansar Dine monitored the activities of local inhabitants at ten mosques and mausolea for several months, but only ordered their destruction after they were inscribed on UNESCO’s list of heritage under threat in June 2012.17 In October, the group re-started destruction on the eve of an international meeting in Bamako, and in December, it was in response to a UN security resolution to send an occupying force to northern Mali that further “hidden mausoleums in the city” were found and attacked.18 In interviews with the Western press, Ansar Dine spokesperson Sanda Ould Boumama performed this mirroring, asking, “We are Muslims; what is UNESCO?” and continuing, as if to question the moral authority of the West’s cult of monuments, “For us, their indignation is an atonement.”19

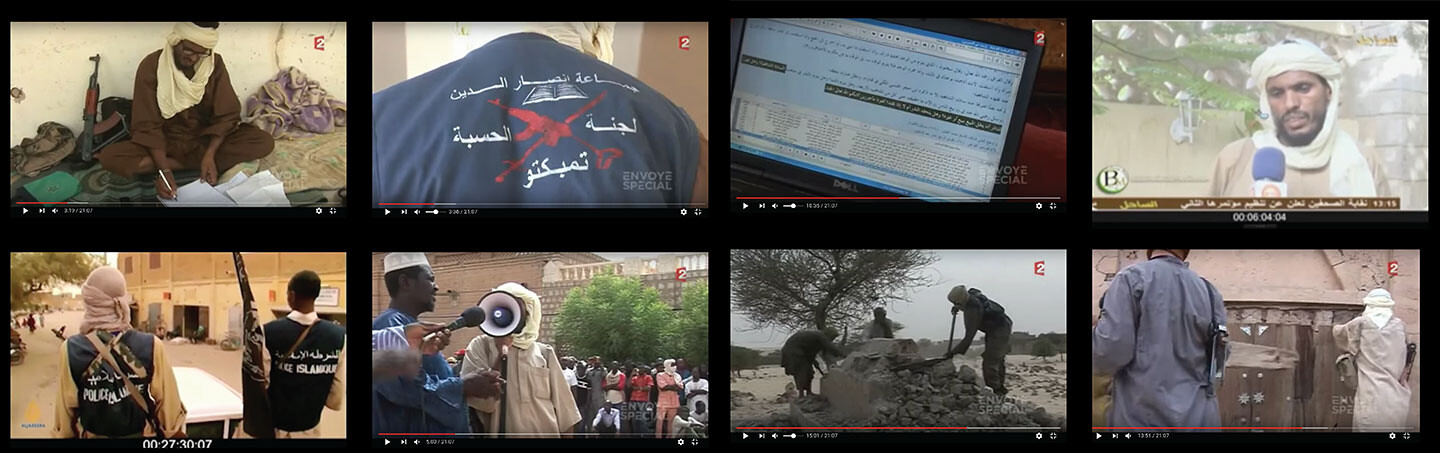

Next, consider Al Mahdi himself. A religiously educated member of a Touareg family, he was a teacher of literary Arabic and a schoolmaster by the time he was recruited into Ansar Dine in April 2012, when he took the name Abu Turab and began travelling as an acolyte of Abu Zadine. When the group returned to Timbuktu to occupy the city, Al Mahdi was enlisted to act as local mediator and, given a choice of positions, became the chief of the “morality police,” al-Hesbah. Video footage from this period (captured by a rare embedded journalist) shows him to be living exactly the kind of life on the surface described by Devji: going from his day job teaching Arabic to a child, to donning a special “vice police” jacket on top of his clothes before he sets off on vice patrol.20 This squad is in charge not of beliefs but of mores; not of the content of the Koran but of its respect; not of the rules but of the sincerity with which they are followed.

Following Al Mahdi on his routine as a morality policeman, the camera catches him alternately conducting online research on Koranic law in a session of the local Islamic court, patrolling the streets with Kalshnikov and megaphone in hand, inflicting the first three of a hundred lashes to an adulterous couple in the public square, assisting in the assassination of one of Ansar Dine’s own and leading a group of men in the destruction, by pick-axe, of a number of buildings.

The architectural destruction fits seamlessly into the joint policing of local morality and global sincerity. “We have destroyed these cemeteries as a preventative measure,” Al Mahdi explains at one point, “in order to make sure the people don’t use them as idols.”21 In fact, Al Mahdi is not originally convinced that the mausolea need destroying. But when he is finally pressured to write a radio sermon calling for their destruction, he finds a Koranic verse forbidding any construction higher than an inch on top of a tomb.22

What ensues is a two-week performance of regulating architectural volumes and surfaces through destruction. At stake is the superficiality of the Western notion of heritage “protection,” to which Ansar Dine counter-proposes that it is the globe and its surface that should be the true object of protection, and not have objects built upon it. Thus tombs are sinful protuberations and their razing “brings protection of Sharia of the unicity of God.”23 Destroying buildings creates a place “upon which the law of Allah can now be applied.”24 Al Mahdi vows to “remove everything that doesn’t belong on the landscape,” as if to prime the surface of the earth for a guest.25 Thinness and superstition are also conflated when the mob arrives at one of Timbuktu’s revered monuments—a sacred door. “There was a legend that if you opened this door it would be the end of the world. We are charged with fighting superstition. This is why we decided to fix the construction of the door.”26 Exposing superficiality, Al Mahdi helps rip out the door by hand to expose a bricked-up, solid wall.27

One of the more remarkable allocutions of Al Mahdi’s destructive rationale comes retroactively, in court, when the presiding judge inquires about the sincerity of his remorse and asks whether he has had to renounce his religious belief to plead guilty. Instead, Al Mahdi notes that this is not his first, but his second change of heart, thereby assuring the court that he had simply learned to live with “the contradiction that the mausoleums represented.”28 To be sure, this represents a betrayal of Al Qaeda’s sacrificial quest, but it also retroactively confirms that this sacrifice was originally demanded in the name not of a historically-grounded tradition but rather to publicize (and destroy) modern hypocrisy.

In court, Al Mahdi himself takes on qualities of an architectural mediator. He is tried not only as the “author” of destruction but as a “media spokesperson,” for his design of a sequence for the destruction. He is charged with “heightening the suffering” of Timbuktu’s population by allowing “armed groups to reach and thus to victimize a broader audience.”29 His choice of destruction techniques (instead of a bulldozer he purchases pick axes, which distribute the destructive tasks) also confers mediatic properties to his mob: they transmit ideology through their actions.30

But if AQIM relies on Al Mahdi as a local connector for implanting itself in Timbuktu, the ICC equally requires him to use his own personhood to depict an expanded field of applicability for international law. The same qualities that Al Mahdi offered to the terrorist network are fully exploited by the ICC: he is a person who can “expand” his identity and belonging concentrically. This is particularly evident in the way Al Mahdi structures his guilty plea, in a statement that repeats atonement in a scalar progression from local brotherhood, to national citizenship, to global humanity:

I am sorry. I am really remorseful and I regret all the damage that my actions have caused to my family. And to my brothers in Timbuktu. And to my home country, the nation of Mali, in general. And to the whole of humanity around the world.31 (al bashariyyati jamaa fi anha’ al alam)

When Al Mahdi uses the word “humanity,” he evokes a ribbon of persons across the globe. But the French and English translations (both in court and in official transcripts) replace this with “international community,” taking advantage of the discursive structure that is shared between humanitarian activism and Islamic jihad.32 Indeed, even if Al Mahdi’s language is far more colorful than its translations, it conveys a struggle with superficiality. He speaks of being “swept up” in an “intense whirlwind,” but argues that despite this destructive force the “deep historical roots (al jothoor al amiqa) of the city of Timbuktu and its inhabitants” cannot be erased. The court translators substitute “root” with “heritage,” and “whirlwind” with “evil wave … of deviant people.” But these substitutions are altogether seamless, because Al Mahdi is one of the few people who can make these linguistic substitutions possible. From an anonymous official, he becomes throughout the trial a crucial operand, who can perform the scalar shift from personal brotherhood to global humanity that is consistent both with the imagined territory of humanitarian law and with the global surface of jihad.

What, then, about heritage practices that were called upon to remediate Al Mahdi’s cultural vandalism? Devji’s concept of “life on the surface” helps to locate the criminalization of architectural destruction within humanitarianism as a privileged vector of moral sincerity in the West, as well as within terrorism and its publicity goals. What is the relationship between this dynamic and the international preservation community, with its well-known preoccupation with integrity and authenticity? Here too the answer lies less in the symbolic weight of Timbuktu’s architecture than in the technologies of protection that have been used to manage its decay, its destruction, and now its reconstruction.

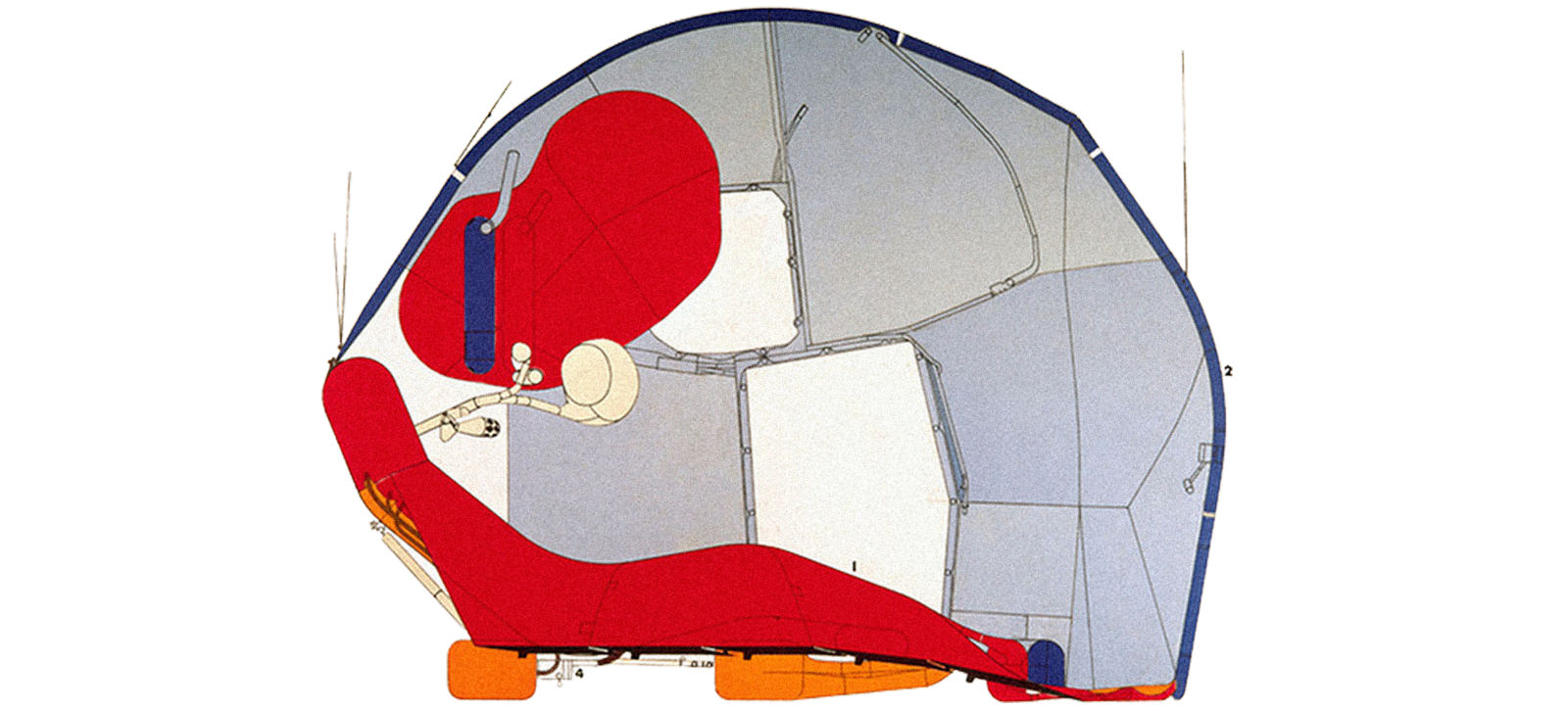

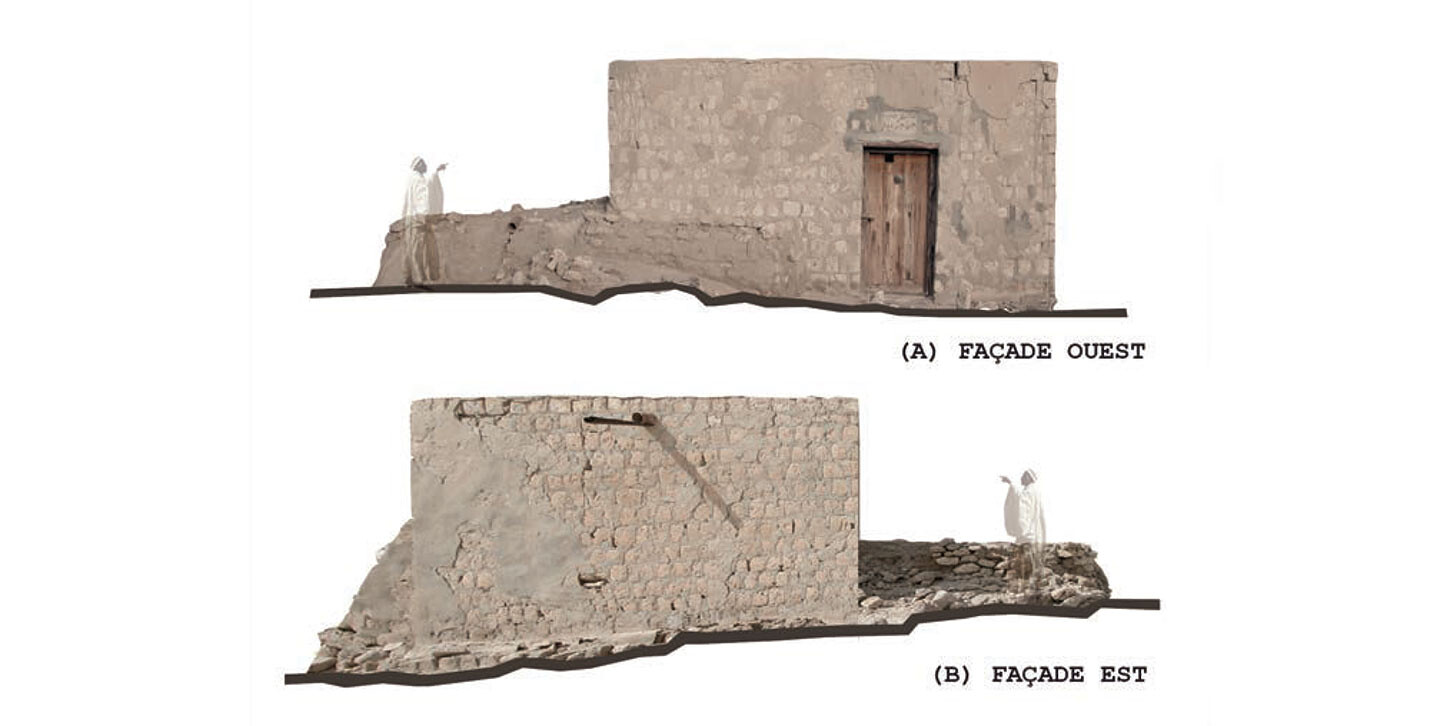

“Facade Ouest” and “Facade Est” for the Cheikh Sidi Ahmed Ben Amar Arragadi, in Pietro M. Apollonj Ghetti Etude sur les Mausolées de Tombouctou (Unesco, 2014).

When Old Ontologies Were New

Two conceptions of heritage were brought to trial in the Hague. The first associates architectural objects with depth and fundament. It offers a vision of heritage as local, situated, and connects the architecture of the buildings to the earth itself. The prosecutor in Al Mahdi’s case, Fatou Bensouda, adopted this view in her opening statement. She invoked the “deep connection between the mausoleums and the inhabitants,” called the destroyed buildings “roots of an entire people” and “important foundational blocks” for the city’s life and recalled their “inherent” or “intrinsic value” which “once destroyed, restoration can never bring back.”33 For her, Timbuktu was targeted as an emblem of cultural diversity, a union of human and material tolerance that was dissolved as soon as “authentic materials [were] destroyed.”34 She further functionalized this architectural ontology in her legal argument, by resorting to the doctrine of military objective (which objectifies the built environment by classifying all buildings as either civilian or military.)35

This argument is entirely in keeping with prevalent international preservation theories that the gap between heritage and humanity can only ever be bridged by a deep essentialism of place. “In order to maintain its authenticity and truthfulness,” Jukka Jokilehto writes, “space must be alive.” Any local community “produces” space through dwelling, and therefore all spatial history (“inheritances,” in this language) is necessarily local, while any contact with a “globalizing world society” provokes an uprooting.36 What is lost in destruction, therefore, is architecture’s inherent sincerity.37

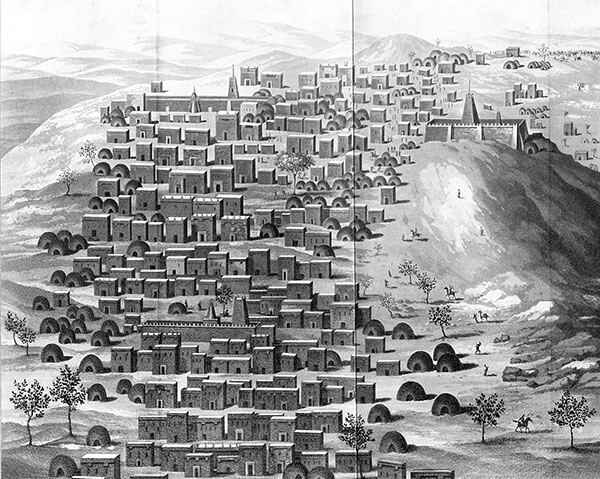

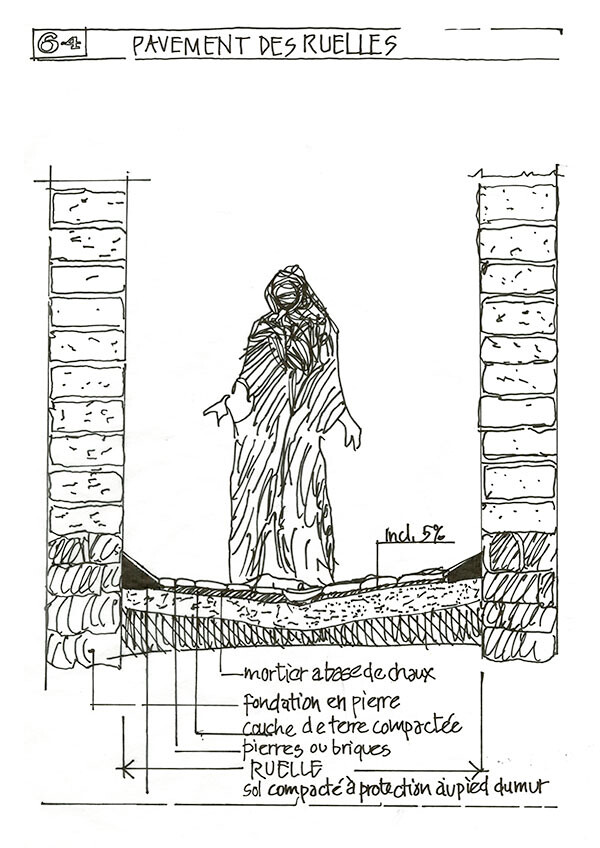

“Paving of alleys” from Mauro Bertagnin et Ali Ould Sidi, Manuel pour la conservation de Tombouctou (Unesco: 2014). Facsimile by François Sabourin

But the material continuities that apparently authenticate these historical lineages are hard to trace. Thus a second view of heritage extends a testimonial power to buildings and affords more room for historical and material ruptures. Here, Bensouda appealed to the continued “memory” of these buildings in several generations, as “living testimony to Timbuktu’s glorious past… a unique testament to the city’s urban settlements.”38 One step removed from ontological dwelling, this chain of communication proceeds through history witness by witness.

In fact, Bensouda also speaks of the mausoleums as media of amplification, and of herself as a transmitter. “It is the voice of the mausoleums, of monuments, which ring out like a bell through my voice … a voice that brings with it echoes for its audience, of hatred or violence or anger.” Bensouda—who has been applauded for her willingness to leverage the “symbolic power” of the ICC—repeats this amplification in her concluding statement giving weight to the judge’s ruling in a scalar concentricity. “Your judgment is awaited from the ancient streets of Timbuktu and throughout Mali to all four corners of the world.”39

It is this media-enabled, amplified humanity (and not a fundamentalist architectural essence) that the judge ultimately designates as the victim of Al Mahdi’s crime. In the final judgment, the court refuses to accept either the “religious nature” or the “high-profile quality” of the attack as an “aggravating circumstance.” Instead, the “far-reaching nature” of the crime is essential to the fact it is aimed at “multiple victims.”40 The gravity of the crime is measured spatially but indirectly, with the idea that international humanity is a mediated, amplified multiple of the local inhabitant.

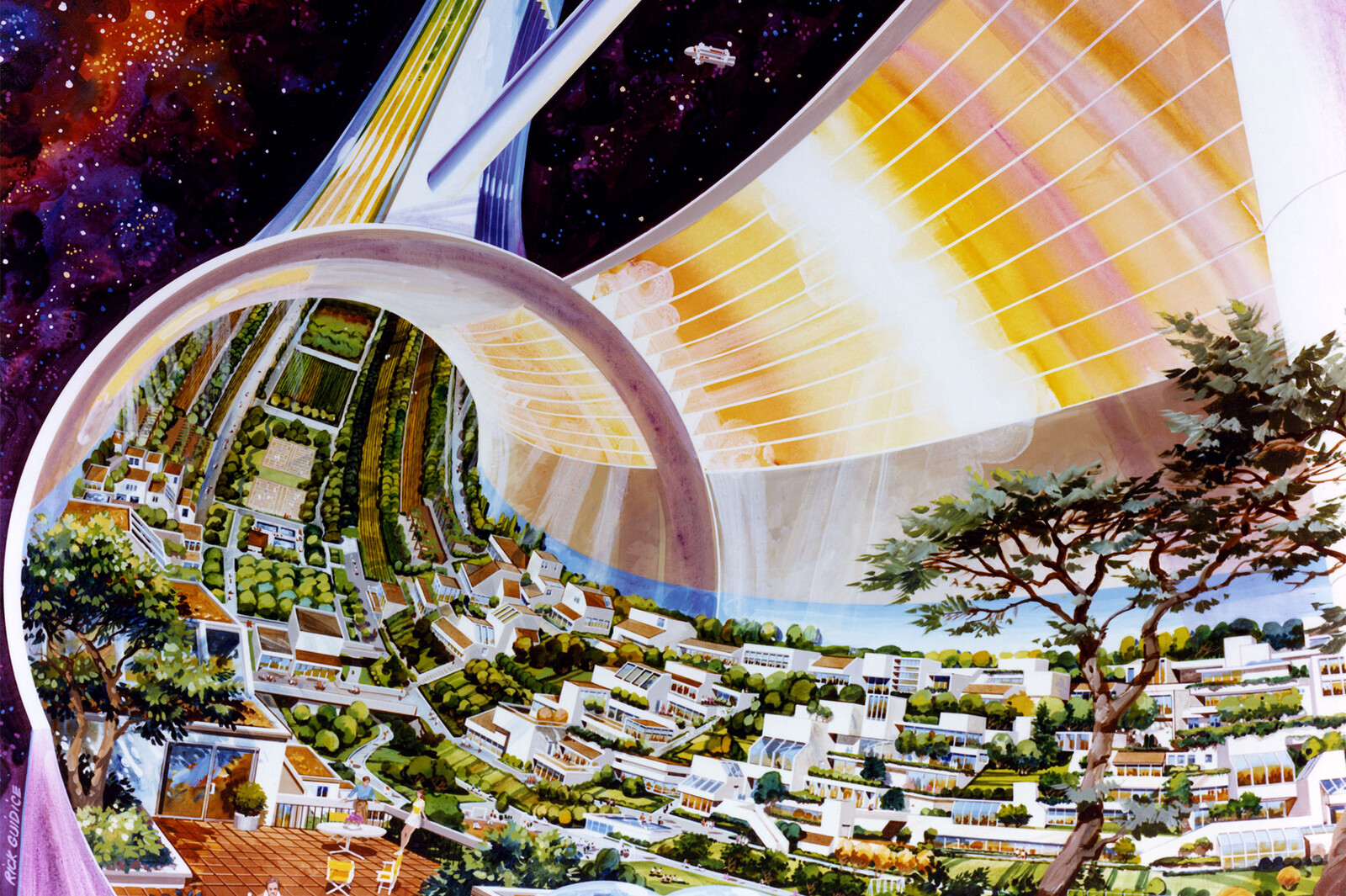

How did the heritage experts who helped rebuild Timbuktu beginning in 2013 take up this challenge of reconciling essentialism and mediality? It was not in fact difficult. Their task was facilitated by pre-existing efforts to bring techno-scientific building practices to bear on a primarily artisanal building tradition. Consider a Manual for the conservation of Timbuktu, published in 2014 to herald the cultural rebirth of the city, but based on research conducted by Italian architects and archaeologists between 2002 and 2006 to protect the city from climate change. The manual depicts the city as a natural product of the “constructive culture of earth.”41 Yet the conservation techniques prescribed in this manual are almost exclusively drainage practices that control the external surfaces of the city’s vernacular construction. One section through a typical city street shows a Touareg scale figure surrounded by meticulously layered, paving and walls. Another shows how to protect the joint between earth and building from water infiltration. Another embeds toilet plumbing inside banco walls. From the care given to these technical images, a casual reader of this manual would be forgiven for thinking that the world-heritage status of Timbuktu pertains only to the thinnest of its outer layers.

But international expertise is concentrated on these surface details for good reason: because the more tectonic aspects of building are delegated to a local community of masons who have for generations, we are told, conserved the city through embodied building know-how.42 They use earth to make either rounded or rectangular earth bricks; they also re-plaster outer walls periodically by hand using sand and water. The material link between these masons and the “earth” out of which they build their architecture is a human, trans-generation apprenticeship, itself designated as intangible heritage under threat.

Implicitly, then, the reasons for this ecological intervention in Timbuktu’s architecture are aesthetic: together climate change and declining know-how have conspired to undermine the objecthood and legibility of Timbuktu. Increased rains mean that water stagnates in the cityscape, and earthen walls are not able to dry through natural evaporation, especially as sand piles surrounding outer walls give water a place to collect and walls rot from within. Masons have responded to the increasing frailty of their architecture by using hybrid building techniques, such as using adding cement to adobe, CMUs and banco bricks, or shoring up failing walls with banco buttresses that jut out into streets. These new practices create an increasingly pile-ridden, formless, ill-defined urban streetscape.43 In other words, the guardians of World Heritage find themselves policing Timbuktu’s masons by constraining their work so that it may only result in sharply outlined, monolithic, objects.

All of these aspects of the thick-thin theory of Timbuktese earthen architecture have made their reappearance in the UNESCO-sponsored reconstruction of Timbuktu’s mausoleums, but the contradiction between depth and surface has now been reconfigured. While ecological disaster seemed to call forth nostalgia for a disappearing tradition, the threat of terrorist destruction makes architecture a medium for the transmitting of a newly construed humanity. In the ICC trial the masons appear as “living human treasures” and, by publishing this manual in 2014, UNESCO makes clear that the goal of reconstruction is in part to give them something to build.44 Through its reconstruction, Timbuktu is now defined as the medial support for the transmission of know-how, not the other way around.

After all, Al Mahdi had intervened in the city’s medial landscape with his megaphone and his laptop as much as with his pick-axe and his Kalashnikov.45 The contest for defining the global “human” continues now, as international institutions continue to publicize their involvement in Timbuktu, keeping its architecture alive by circulating it on networks of communication.46

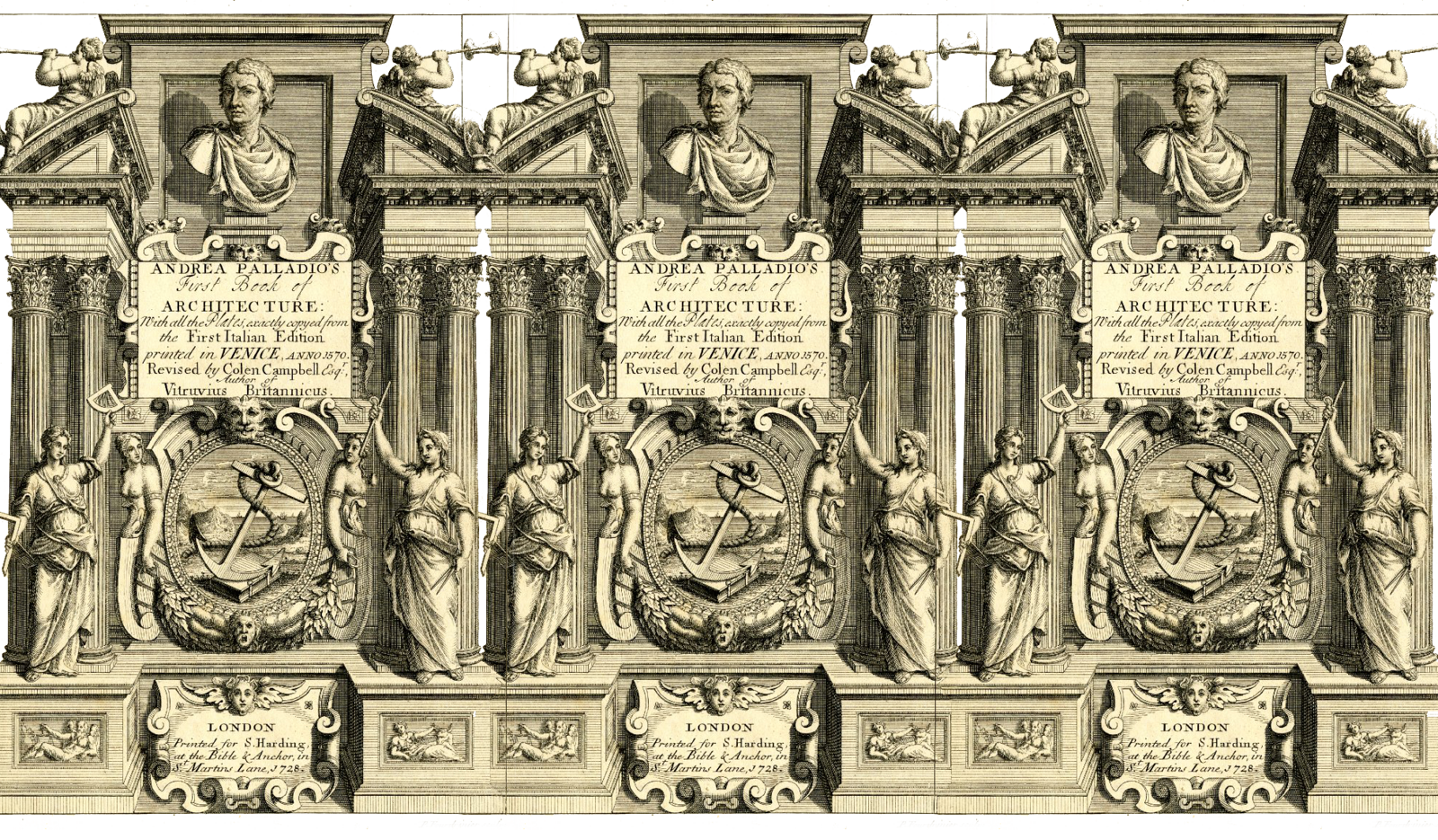

After the destruction and reconstruction of its mausoleums, Timbuktu’s architectural history becomes a media archaeology, one which may help get past the pitfalls of colonialist histories. After all, the inaugural definition of Timbuktu as a place of protuberations was colonial. Robert Caillié’s famous engraving of the “city of 333 saints,” still reproduced in heritage manuals today, saw religious diversification literally materialized in a proliferation of buildings.47 Now, instead, the original context in which Timbuktu will take its architectural significance is that of a network of pilgrimage, commerce, and tourism both real and virtual. In the words of the court, Timbuktu was the “protective heart” of Mali’s heritage because it has been a focal point of cultural mobility since the middle ages.48 And with protection now understood to be the original function of Timbuktu’s destroyed mausoleums, their reconstruction can be seamlessly integrated to their history.49

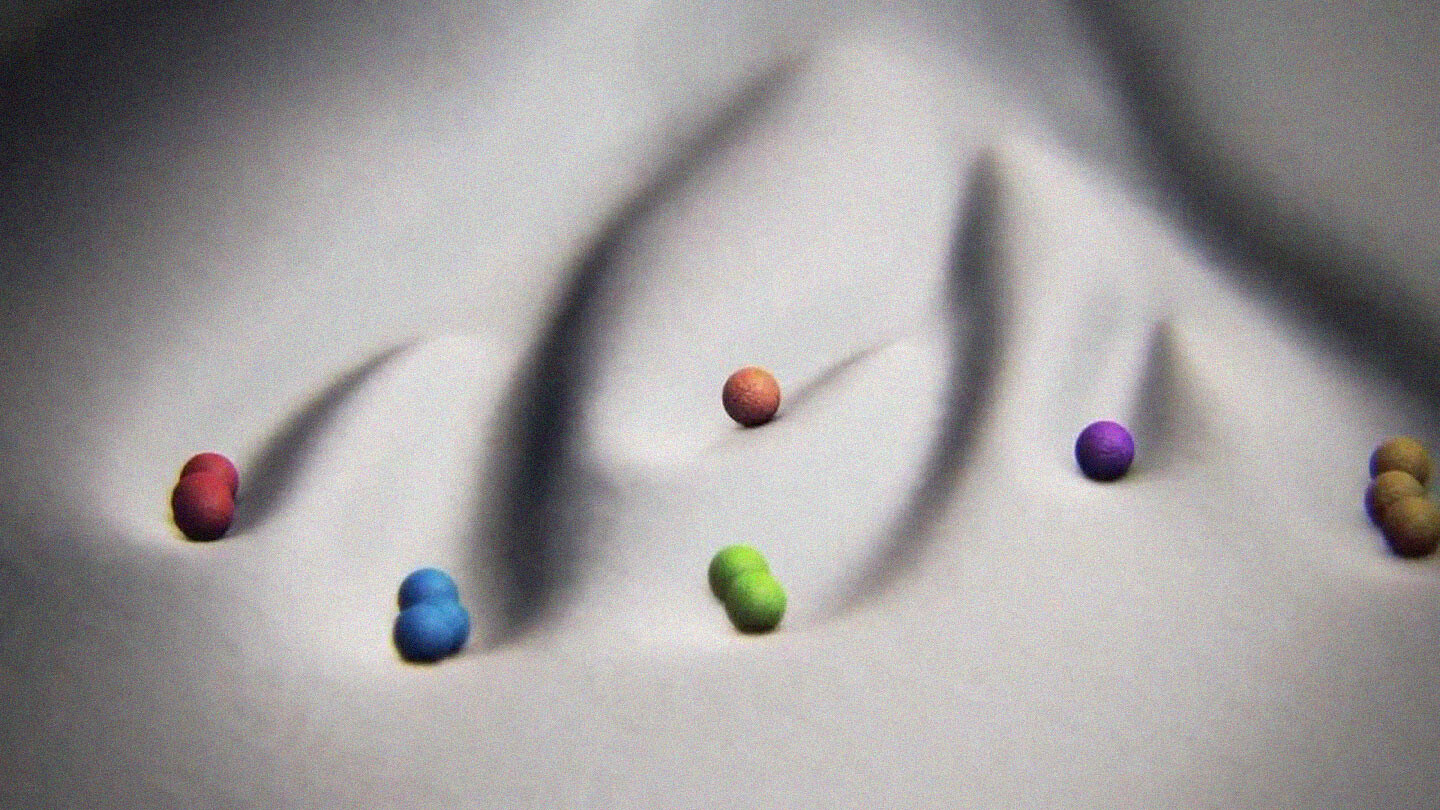

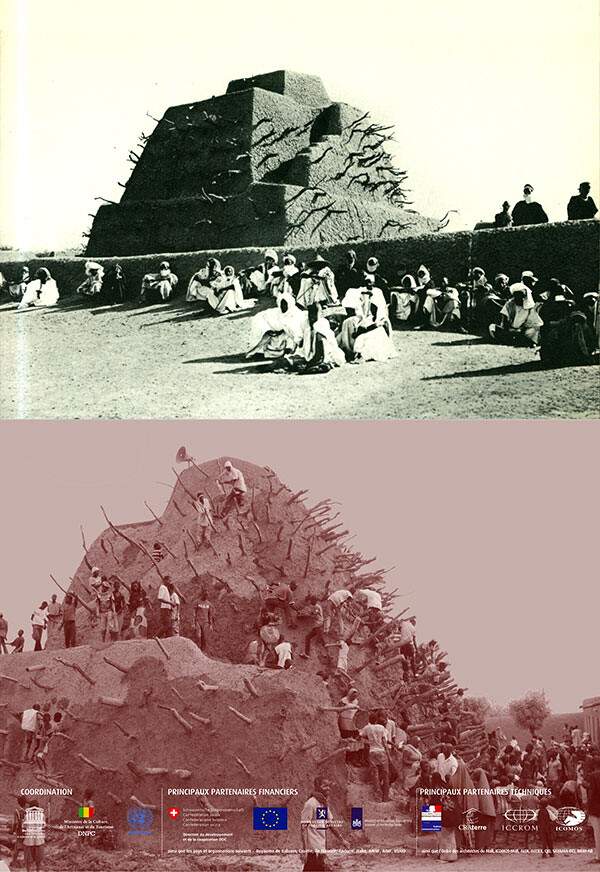

Timbuktu’s architectural history as a protective shield has not been interrupted by the destructions of 2012; rather it has been increasingly materialized. The city was already mediatized when technologies of communication were embedded in its urban architecture and its landmarks.50 In the 1990s, the Djingareiber Mosque was wired and loudspeakers were lodged among its dome’s distinctive wooden stakes. Between 2002 and 2006, Timbuktu’s urban fabric was surveyed through plans that encircled buildings with markers signifying the positions of photographers. After their destruction, the rebuilt mausoleums have been inventoried not through simple photography but with data-rich photogrammetric scans, with a ghostly scale figure digitally added in. UNESCO hopes that reconstruction will reclaim the warscape the city had become under Ansar Dine, through new acts of medial-architectural presencing.51 For example, when masons climb atop mosque towers during their yearly “ritual maintenance event” and pose for a publicity shot, the architectural festival itself is not new, but it is has now become a performance of retracing, reproduction, that takes place on the very surface of what colonial visitors called “a noble pile.”52 Photographic surveying and participatory masonry have created a new standard for authenticity, where geometric exactitude recedes and live approximation triumphs.53

Central structure of Askias Tomb in Gao, Mail, originally built in the 15th Century. Top during a colonial visit in the early 20th Century; Bottom: photographed during a maintenance festival in July 2014, sponsored by a number of international agencies.

The Lure of Evidence

From a place for the multiplication of saints, Timbuktu has become the site for an amplification of humanity. It is undoubtedly this power of amplification that prosecutors and activists are hoping to avail themselves today to activate the proximity of heritage and humanity. When heritage advocates argue, after Raphael Lemkin, that cultural destruction tends to precede human violence; that vandalism must be prosecuted to “signal” that no other violence will be tolerated—it is because violence against heritage and humanity circulate by the same means.54 But even when it occurs in the same place, the broadening of heritage into humanity is mediated. This is why architectural forensics is an urgent issue, and its practitioners are keenly attuned to the evolution of new media.55

Yet when architectural evidence is brought to the Hague, the argument that heritage and humanity are united by collective identity, by dignity cemented through dwelling, is not sufficient. The architects’ cameras that penetrated Timbuktu’s interiors in the 2000s to survey its urban fabric, could not produce evidence of the sexual crimes that those same walls may have witnessed in 2012. On today’s international stage, any ontology will be tested against an evolving definition of humanity as fueled by “negative solidarity.” The architectural criminal mirrors the morality claims of the humanitarian, including those of her evidentiary regimes. After all, when the Court attempted to penetrate Al Mahdi’s internal life, he performed an outward extension of personhood instead.

Protecting Cultural Heritage: An Imperative for Humanity, United Nations Brochure (22 September 2016), produced on the occasion of the “high-level meeting” at the United Nations, 10.

Vandalism on the world stage is nothing new, nor is its prosecution as a violation of international norms. A crucial precedent was set by the International Tribunal established in the aftermath of the Balkan wars, which tried and convicted criminals for “intentional cultural destruction.” But the Dayton Accords this Tribunal enforced pertained only to one conflict, conscribed in space and time. On this, see Andrew Herscher, Violence Taking Place (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010). In contrast, the International Criminal Court prosecuted Al Mahdi for his violation of a prohibition against “intentionally targeting cultural sites” that makes up Article 8 of the Rome Statute, an agreement that originates in a 1998 agreement to establish a permanent international judiciary.

Among those pushing for this bridging are journalists such as Robert Bevan, “Attacks on Culture to be Crimes against Humanity,” The Art Newspaper (27 September 2016) and scholars such as Stener Ekern, William Logan, Birgitte Sauge, and Amund Sinding-Larsen, “Human rights and World Heritage: preserving our common dignity through rights-based approaches to site management” International Journal Of Heritage Studies 18/3 (2012), 214-354. In Africa, the phrase “crime against world heritage” has been circulated; see Slimane Zeghidour, “Crime contre le patrimoine de l’humanité” in TV5 Monde (11 March 2015) →. In Western elite preservation circles, the two terms have also been cross-pollinated, as when Renzo Piano’s addition to a building by Le Corbusier was called a “crime against humanity.” Michael Z. Wise, “Confrontation at Art Museums,” ArtNews (29 October 2014). The film version of Bevan’s book The Destruction of Memory (dir. Tim Slade, 2014) features a number of international figures arguing for new “conjoining” heritage and humanitarian law. Most prominently UNESCO Secretary General Irina Bokova declares “You don’t choose between lives and monuments because it’s about identity.” On the differentiation between humanism and humanitarianism in the construction of international architectural heritage value, see Lucia Allais, “This criterion should preferably be used in conjunction with other criteria,” Grey Room 61 (Fall 2015): 92-101.

Rafael Lemkin, the author of the Genocide Convention, originally included “vandalism” in his definition of genocide but dropped this aspect when it threatened the passage of the convention. See A. Dirk Moses, “Raphael Lemkin, Culture, and the Concept of Genocide,” in Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies (Oxford: University Press, 2012).

International Criminal Court, Summary of the Judgment and Sentence in the case of The Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi (26 September 2016), 10.

This is a distinction reiterated in 1938 by Erwin Panofsky, “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline,” (1938) reprinted in Meaning in the Visual Arts (New York: Doubleday, 1955), 1–2.

The prevalence of video evidence was a factor in the court’s decision to take on the Al Mahdi case for cultural property crime alone, producing what Foreign policy calls “an evidentiary slam-dunk” →. But it was his confession that established the “gravity” of the crime and its punishment.

See Association Malienne des Droits Humains, “Mali: La comparution d’Abou Tourab au CPI est une victoire, mais les charges à son encontre doivent être élargies,” (30 September 2015). To argue for “widening” the charges they wield a combined language of heritage and humanity, see →. Erica Bussey of Amnesty International argued along similar lines in the Guardian →.

Faisal Devji, The Terrorist in Search of Humanity: Militant Islam and Global Politics (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008).

Hannah Arendt, “Karl Jaspers: Citizen of the World?” (1957) in Men in Dark Times (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968).

Far from a tabula rasa, the landscapes of destruction that increasingly patched the globe after the first world war were shaped around architectural objects that had been designated for survival, singled out for reconstruction, or both. This history of monument survival is the subject of my forthcoming book, Designs of Destruction: Monument Survival and internationalism in the 20th Century.

Faisal Devji, “A Life on the Surface,” 21 September 2015, Hurst Publishing →.

Vyjayanthi Rao, “How to read a Bomb: Scenes from Bombay’s Black Friday,” in Public Culture 19, no. 3 (2007): 567-592, cited in Ibid., Devji (2008), 51.

Ibid., Devji (2015).

Like many other groups in the Sahel, Ansar Dine has shifting alliances within global terror networks. At the time of the destruction it was allied with Al Qaeda, but also also hosted recruiters and preachers coming through Timbuktu from a constellation of other groups. ISIS’s cultural targeting became systematic in Mosul in June 2014, when the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Shām issued a “Charter of the City” announcing that “all shrines and mausoleums” would be razed. Cited in Aaron Zelin, “The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria Has a Consumer Protection Office” The Atlantic (13 June 2014).

In “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum Author(s) The Art Bulletin, 84/ No. 4 (Dec., 2002), pp. 641–659, Finbar Barry Flood already critiqued the essentialist view of Muslim iconoclasm as a cultural pathology by inscribing the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddahs within tropes of global modernity, especially as a response to the “hypocrisy of Western institutions.” I wish to thank Byron Hamman for reminding me of this seminal article and for thoughtful comments on a draft of my own text as well.

Ansar Dine’s monitoring and patrolling of the sites was one reason for the UN’s decision to place them on the list of endangered cultural property. United Nations Press release, “Mali site added to List of World Heritage in Danger – UNESCO,” 13 July 2012 →. The ICC also noted that the destruction was a response to the initiatives of the Malian ministry of culture begun in 2013.

“Les Islamistes détruisent les derniers mausolées de Tombouctou” L’express with AFP (23 December 2012) →.

“Les Islamistes poursuivent la destruction des monuments de Tombouctou,” L’express with AFP (1 July 2012). These citations were made to Agence-France-Presse over the phone, reported widely (see for instance “A Tombouctou, les islamistes détruisent les mausolées musulmans,” Le Monde with AFP (30 June 2012) →. This citation is from the ICC’s own “unofficial internal translation” for the video MLI-OTP-0034-0395: “Our reference is not to international law, nor the United Nations, nor UNESCO … These international bodies … don’t concern us, and for us their indignation is an atonement … What is the value of these walls?” See also an interview of Sanda Ould Boumama by Marie-Pierre Olphand of RFI, “Mali: la destruction des mausolées de Tombouctou par Ansar Dine sème la consternation,” (10 November 2013), which became evidence MLI-OTP-0007-0228, and MLI-OTP-0020-0584.

These videos, which serve as the core evidence in the ICC’s case against Al Mahdi, were shown in an elaborate multimedia presentation during trial. Originally they were recorded by a Mauriantian videographer, Ethnam Ag Mohamed Ethman who was embedded with Ansar Dine for months. Ethman periodically broadcast them on Saharamedia (for example, for June 20, 2012). Eventually they were acquired by producers and reporters from France 2, and broadcast in Envoyé Spécial on January 31, 2013 as part of the report Mali: La vie sous le régime islamiste” →. Henceforth Envoyé Spécial.

The Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, Trial Chamber VIII, 24 August 2016: ICC-01/12-01/15/T-6-ENG, 11. Transcript from ICC trial indictment (12 January 2015).

The ICC documents describes this as a rule against building anything measuring over “an inch” while press reports say “building anything that is taller than the span of a hand.”

Envoyé Spécial 15:07—15:30. “Settling the graves” is taswiyat al qoboor. Translation from original Arabic by Leen Katrib

“If a tomb is higher than the others, it must be leveled (…) we are going to rid the landscape of anything that is out of place” Cited in “The prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi,” Public Judgment and Sentence, 27 September 2016, (ICC-01/12-01/15), 20–21. “Un homme remercie Dieu après avoir détruit un tombeau plus protubérant que les autres; un autre qui loue Allah de leur avoir accordé toutes ses victoires et de leur avoir permis d’appliquer Sa Loi sur terre.” “Sahara média accompagne Ançar Edine en train de démolir les mausolées de Tombouctou,” Saharamedia (30 June 2012) →.

See note 19.

Envoyé Spécial 14:00—14:30. Translation from original Arabic by Leen Katrib.

“The door was condemned and bricked up. Over time, a myth took hold, claiming that the Day of Resurrection would begin if the door were opened. We fear that these myths will invade the beliefs of people and the ignorant who, because of their ignorance and their distance from religion, will think that this is the truth. So we decided to open it.” Cited in Trial Chamber VII, Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Public Judgement and Sentence, (ICC-01/12-01/15-171), 22.

In response to the question, “have you changed your religious conviction?”, Al Mahdi replies: “If you review my former statements, you will see that I was not convinced originally with the appropriateness to undertake such actions from the beginning because the decisions I had made were made on the basis of a legal decision. I said that what I did was based on a theory according to which one cannot build anything on tombs, and a tomb, according to the religious beliefs, should not be over 1 inch above the ground, and those mausoleums are far higher than that. (…) But from a legal and political viewpoint one should not undertake actions that will cause damage that is higher or more severe than the usefulness of the action. Such mausoleums I believe are not as harmful as the contradiction they represent as they are built on tombs, but the people who controlled the country at the time considered that such. (…) Thus, I believe that by doing that I do not change my beliefs, I should not undertake action that will cause damage to others. This is a former belief and a present belief of mine, sir.” Trial Chamber VIII, Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, 23 August 2016 (ICC-01/12-01/15-T-4-Red-ENG), 13.

“We are not here to decide on the fate of the author of single act of vandalism, but to render justice to memory and affirm the importance of symbol in the existence of a people.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, 24 August 2016. “His role as media spokesperson in justifying the attack” is from Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Public Judgement and Sentence, 27 September 2016, 39-42.

This choice of tools was also noted by the press. See →.

The English translation and transcription is Prosecution v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, 23 August 2016 (ICC-01/12-01/15-T-4-Red-ENG), 8–9. The French is ICC-01/12-01/15-T-4-Red-FRA. This and following quotations of Al Mahdi’s statement are re-translated by Leen Katrib from the Arabic video, not transcribed but made available by the court as “In the Courtroom Programme.”

Also critical to Al Mahdi’s performance as an international witness was the somewhat belabored procedure of his choosing a language for the trial. Being asked which language he preferred, al Mahdi chose Arabic, indicating his exo-graphic affinity is with global Islam rather than, the State of Mali whose official language is French. When he indicated this choice through his lawyer, however, the presiding judge replied that he should have spoken this choice himself. Once al Mahdi obliged, the judge then ensured an Arabic simultaneous translator, and asked all parties not speaking Arabic to pause periodically to allow this interpreter to keep up with proceedings.

“This is how deep the connection is between the mausoleums and the people of Timbuktu … to erase an element of collective identity.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, 22 August 2016, 21.

Ibid.

“He acted with the requisite degree of knowledge. He knew that the buildings targeted were dedicated to religion and had a historic character and did not constitute military objective” Trial Chamber VIII, Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Confirmation of Charges Hearing, 24 March 2015, (CR2016_02424), 25.

Jukka Jokilehto, “Human rights and cultural heritage,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 18, no. 3 (May 2012): 226–230.

Accordingly, Bensouda cited an elderly man captured on camera, declaiming the loss of the city’s “soul.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Transcript, 22 August 2016, (CR2016_05767), 19.

“These monuments, your Honours, were living testimony to Timbuktu’s glorious past … a unique testament to the city’s urban settlements. But above all they were the embodiment of Malian history, captured in tangible form from an era long gone yet still very much vivid in the memory and pride of the people who so dearly cherished them.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Trial Hearing Transcript, 22 August 2016, (CR2016_05767), 17

Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Transcript, 22 August 2016 (“CR2-16_05757”), 24.

The prosecution argued that the “multiple victims” aggravated the crime, while the chamber countered that it had “already taken into account the far-reaching nature of the crime.” “World Heritage” status means that the crime “not only affects the direct victims of the crimes (namely, the faithful and inhabitants of Timbuktu) but also people throughout Mali and the international community.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Transcript 24 August 2016 (“CR2-16_05730”).

Mauro Bertagnin et Ali Ould Sidi, Manuel pour la Conservation de Tombouctou (Paris: Unesco, 2014).

See “Analyse et constat: Dégradation des bâtiments” and “Les matériaux de la tradition et le rôle des maçons” in Manuel pour la Conservation, pp. 61-70. See also Ali Ould Sidi, “Monuments and traditional know-how: the example of mosques in Timbuktu”, Museum International 58, 1-2, 229-230; “Timbuktu: Mosques face Climate Challenges” World Heritage Review 42 (2006), 12-17, and “Partnership to preserve Timbuktu”, World Heritage Review 29 (2009), 16-17.

Ibid., Manuel pour la Conservation, 61.

For Bensouda, rebuilding and regular architectural maintenance, in an allegory for peacemaking itself, “contributing to the workshop of peaceful coexistence.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Transcript, 22 August 2016, 24.

I take inspiration here from Brian Larkin’s description of the mediality of the loudspeaker in Jos, Nigeria, a city where both daily life and conflict are, as in Timbuktu, mediated through techniques and technologies for attention and inattention. Brian Larkin, “Techniques of Inattention: the Mediality of Loudspeakers in Nigeria,” in Anthropological Quarterly 87(4), 989-1016.

Pietro M. Apollonj Ghetti, Étude sur les mausolées de Tombouctou (Paris: Unesco, 2013).

Robert Caillié, Voyage à Tombouctou, (1830) Facsimile (Paris: La Découverte, 1996).

Francesco Bandarin’s testimony at the ICC notably weaves together three themes of Timbuktu’s architecture to argue for its multivalent historical value: a site of material know-how, of religious aura, and an urban network that is a “focus point for religious life, the region… and focus for pilgrimage” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Transcript, 23 August 2016, 44.

Even Timbuktu’s famous manuscripts, which had been meticulously digitized before 2010, have been re-released into networks of global mobility. Originally housed in new museums on site, they were smuggled to Bamako before Al Mahdi’s group was able to get to them, thanks to a network of globally-trained curators, funded in part by a Ford Foundation grant. These funds had originally been granted in a “multidimensional and integrated United Nations initiative for stabilization” (MIUNIS) to Abdel Kader Haidara, a collector and librarian in Timbuktu, to conserve these manuscripts on site. They were officially diverted to help for the secret removal of these objects to Bamako by boat and car. “Trois Bibliothèques de manuscripts anciens réhabilitées à Tombouctou,” UN Press Release (1 December 2015) →.

On this history see Mary Jo Arnoldi, “Cultural Patrimony and Heritage Management in Mali” in Africa Today 61/1, (Fall 2014), pp. 47-67

On Timbuktu as a warscape see Fiona McLaughlin, “Linguistic warscapes of northern Mali,” in Linguistic Landscapes 1:3 (2015), 213-242.

On the use of these rituals in post-war reconciliation in both Timbuktu and Gao see Thierry Joffroy and Ali Ould Sidi, “Stratégie de reconstruction du Patrimoine Culturel détruit ou endommagé des regions du nord du Mali,” in Mali, post-crise: de nouvelles perpsectives pour le patrimoine (Paris: Riveneuve, 2015), 337-350. “Noble Pile” is from a description of one of the towers of the Djingareiber mosque by Heinrich Barth, Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa 1849-1845 a Vol, III. (London: Frank Cass & Co, 1965), 323.

Daniel Monk and Jacob Mundy have described the post-conflict environment as an ideological construct, a “reification” that helps to realize the interventionist habitus of the liberal international community. Daniel B. Monk and Jacob Mundy, “Conclusion,” in The Post-Conflict Environment (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press,2014), 219. While theirs is a critique primarily of statebuilding practices, it applies equally to softer cultural forms of post-conflict pacification such as the ones operated in Timbuktu, where urban heritage is reified along with the humanity that is produced in its defense.

Bensouda argued during the trial that “attacks on religious property are usually the precursors to the worse outrages against population” and therefore cultural punishment was “an integral part of humanitarian efforts.” Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi Transcript, 22 August 2016, 21. She is a vocal proponent of the use of the ICC to prosecute “sexual violence in conflict.” Esther Addley, “Fatou Bensouda, the woman who hunts tyrants,” The Guardian (5 June 2016) →. The idea of cultural violence “signaling” the presence of other human rights violations, and of the ICC trial “signaling” international policing in return, is articulated by Patty Gerstenblith and Bonnie Burnham in The Destruction of Memory. Raphael Lemkin himself wrote in 1923 that “physical and biological genocide are always preceded by attacks on cultural symbols.” Moses, Op Cit, 41.

See Laura Kurgan’s ongoing work to “document and narrate” the urban damage in the Syrian city of Aleppo, Conflict Urbanism →, and Eyal Weizman’s group’s work, collected in Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014).

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Subject

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.