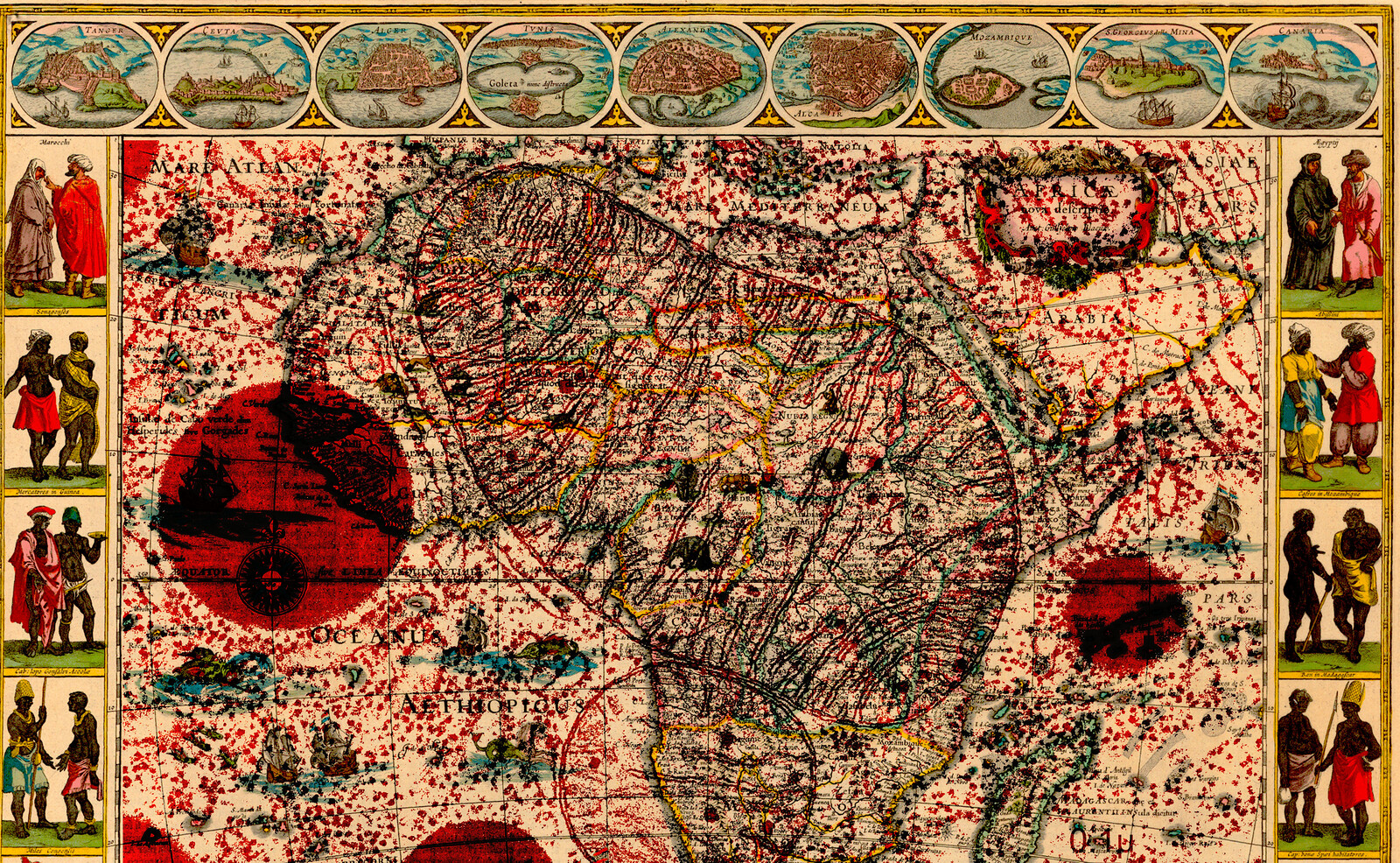

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—the period when the conceptual framework of the “state of nature” reshaped moral, legal and political philosophy —European forests, new technologies for extracting carbon traces from arctic ice reveal, were taken down at the fastest rate to date.1 The great forests largely turned into cropland and fuel prior to wood’s replacement with coal as Europe’s main source of energy, and the colonial economy’s appetite for ships finished off the rest, with merchant ships and gun boats requiring between 4–6,000 mature oaks—several hectares of forest—each.

While some pockets of woodland did survive, primarily in the less densely populated terrain of the Alps, the Pyrenees, parts of the Balkans, and other areas of southeastern Europe, the line separating field from forest was shifting at an unprecedented speed, retreating north well past the Baltics to southern Scandinavia, Scotland and northern Siberia, and south into the northern Balkans. Abraham Bosse’s etching for the 1651 frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan depicts the figure of the sovereign rising over deforested hills. This is not a coincidence: in the European imagination of the time, the forest line still marked the limit of sovereignty, the areas of productive economy and thus also the threshold of the law. Sovereignty could only rise over cultivated nature—that is, over a destroyed ecosystem.2 By the end of the eighteenth century, the forest line has ebbed miles north of Edinburgh. With the exception of David Hume, who was settled there, European philosophers using the concept of the “state of nature” to describe an era prior to law and the social contract experienced nothing more than tamed local woodlands, stranded within an ocean of fields.

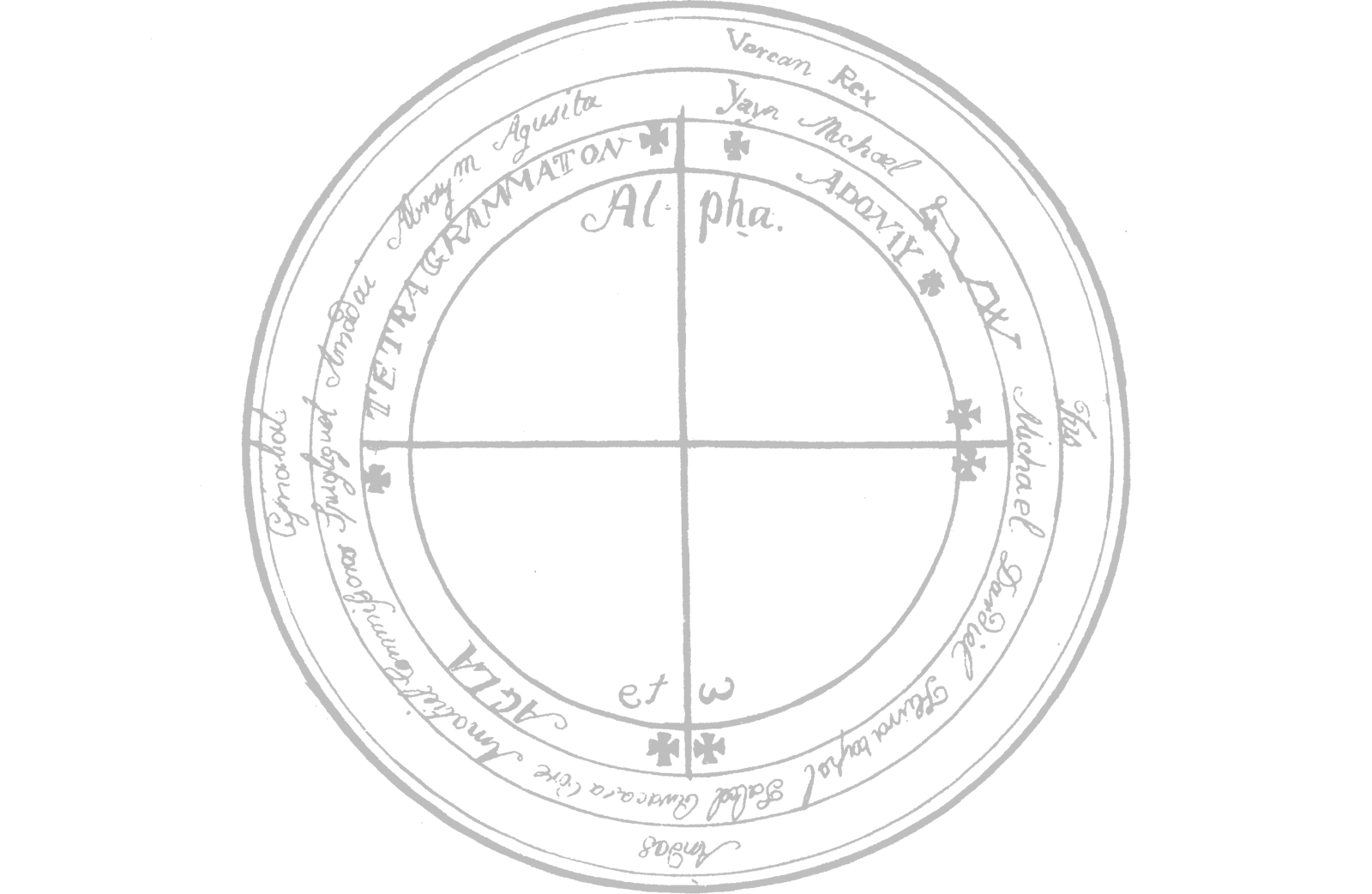

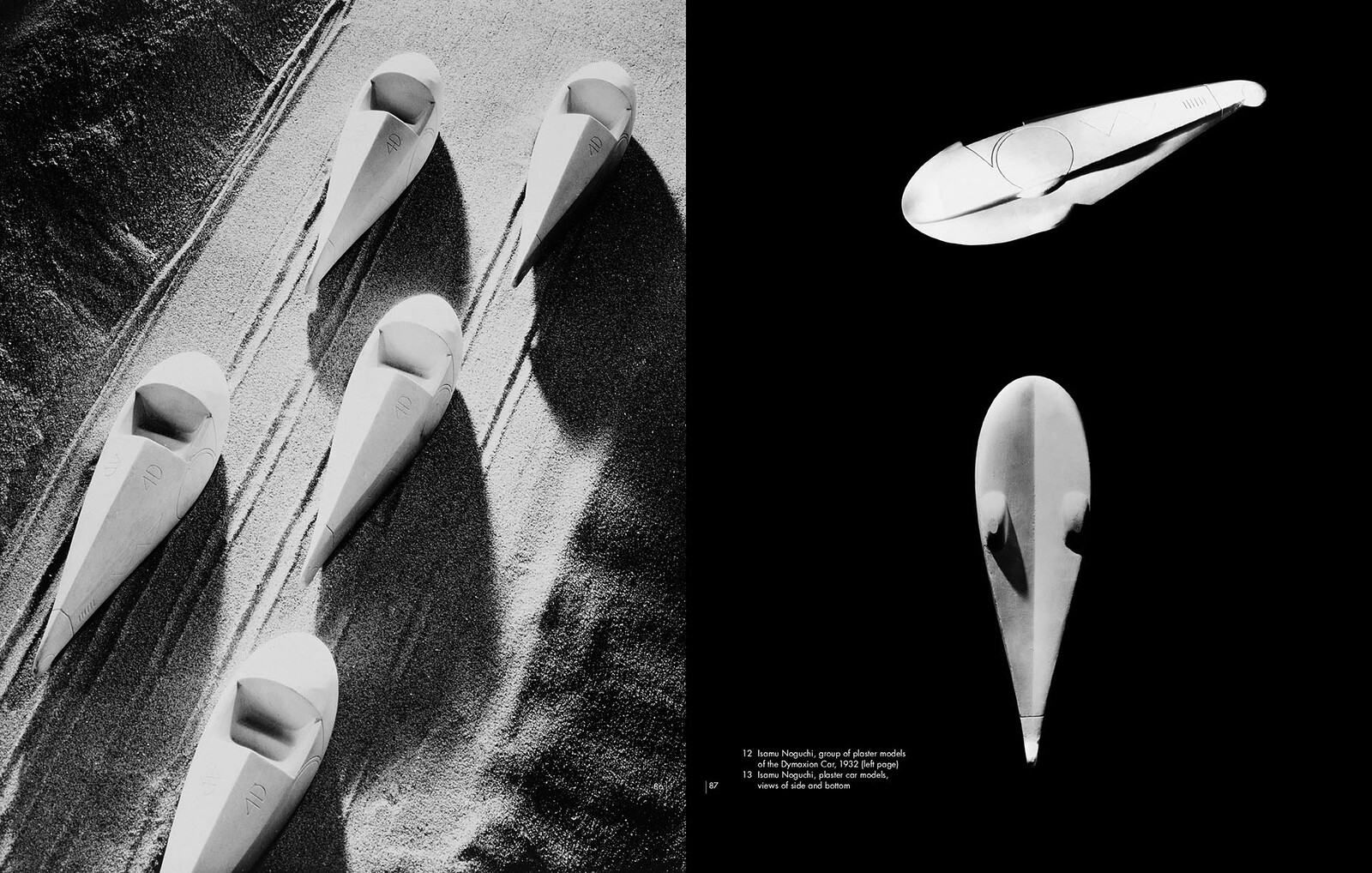

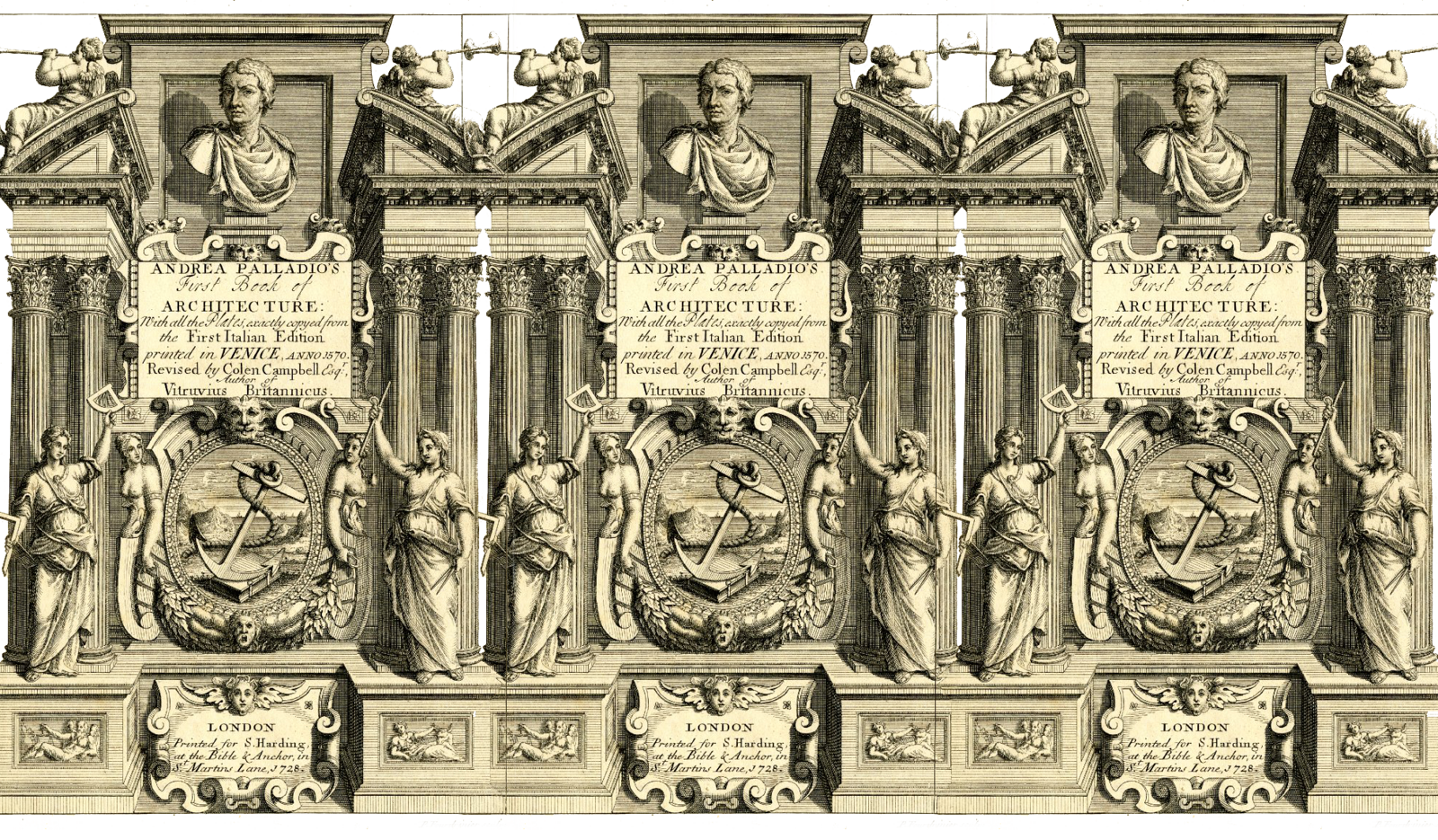

The Master of Deforestation: A detail from the frontpiece of Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651) illustrated by Abraham Bosse.

The hypothetical forest of the “state of nature” was a vast pre-judicial zone, the mythic limit to culture and law. The outlaw and the werewolf, and later the indigenous residents, were humanlike creatures that could be killed without the slaying being considered a murder. With the conversion of European forests into fields, cities, and ships, other forests were discovered beyond the oceans Europeans crossed by floating on their own decimated ones. Those that most captured the European imaginary of the state of nature were found along the equatorial belt in the tropics: Central Africa, South East Asia and Central America. Today we know, from such works as that of Paulo Tavares’ and others, that these forests, in contrast to their Western perception at the time, were environments cultivated by human civilizations and imbued with their own conceptions of politics and law.3

Accounts of these impenetrable forests reached seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe by colonial travelers, settlers, traders, and cartographers who had penetrated their dense biomass, unbearable heat and disease. This second encounter with the forest provoked European philosophers to think about the origins of society, savagery and human nature. From the perspective of these early moderns, the “state of nature” was now no longer separated from civilization in time—that is, a condition prior to the foundation of society and legal order—but rather coincided with it in space. Existing beyond this shifting boundary was an extra-territorial space, conceived under the imperial and racist framework of terra nullius which ignored the social structures and forms of ownership of indigenous people and regarded them as “part of the natural environment.”

Of the most challenging things Europeans recorded beyond the receding thresholds of the forests were great apes. Perceived as “intermediate animals,” these creatures embodied the ethical uncertainty that plagued the imperial process of colonization. From then on, as Donna Haraway explained in her groundbreaking Primate Vision, apes inhabited the blurry and murky border both between animals and humans and nature and culture.4 During early Enlightenment three limit conditions were thus brought into relation with each other: the threshold of the forest—a shifting environmental condition together with its unique climate; the threshold of the law—the political limit of territory and sovereignty; and the threshold of the human—a blurry limit to the human species. Each of the three of these then became, and continue to be, entangled frontiers; shifts made in one challenge all others.

First Encounters

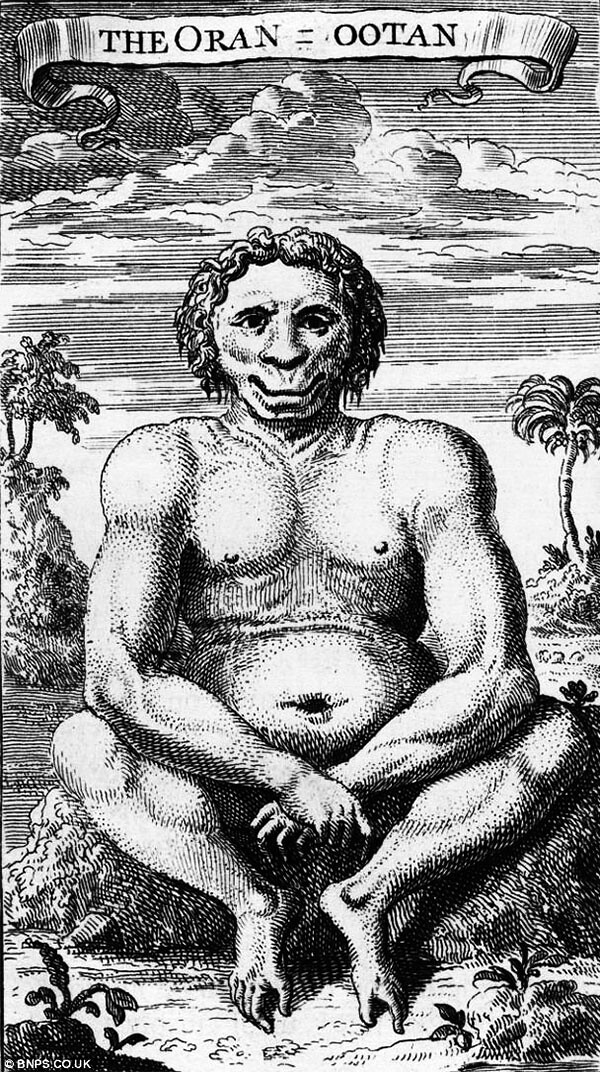

Apes were first described as strange animals, monsters or satyrs, which were, following medieval iconography, a reflection of man’s drives, lust and sins. Gradually, however, their difference from monkeys started to be appreciated. Apes, like humans, have no tails, and questions regarding their potential humanity started to emerge. Robert Cribb, Helen Gilbert and Helen Tiffin’s masterful Cultural History of the Orangutan is full of accounts of confused first encounters between Europeans and tropical apes.5 The first European description of an orangutan (which in its original Malay means “man of the forest”) was recorded by Nicolaes Tulp, a Dutch physician and eventual four-term mayor of Amsterdam, in 1641, and accompanied by an etching of a friendly and embarrassed looking female orangutan. The drawing emphasized her more human features, such as her smile and modest posture in covering her sexual organs with the palms of her hands. Along similarly blurry lines, Jacobus Bontius suggested that the “ourang outangs” were the result of intercourse between humans and beasts. And what the Scottish sea captain Alexander Hamilton actually saw when he described an orangutan that “blows his Nose, and throws away the Snot with his Fingers, can kindle a Fire, and blow it with his Mouth. And I saw one broyl a Fish to eat with his boyled Rice,” is ultimately unclear.6 Some travelers thought orang-utans to be one of the strangest and most exotic forest people of Southeast Asia. Others thought, that despite all these points of resemblance, just like other animals, orangutans were essentially different from humans in that they lacked a soul.7

Illustration of an “oran·ootan” by Daniel Beeckman in A Voyage to and from the Island of Borneo (1718), 37. Beeckman describes a young Orangutan he bought in Borneo (Kalimantan): “[he] loved strong Liquor; for if our Backs were turned, he would be at the Punch-bowl, and very often would open the Brandy Case, take out a Bottle, drink plentifully, and put it very carefully into its place again … If at any time I was angry with him, he would sigh, sob, and cry, till he found that I was reconciled to him.”

Though scientists now differentiate between four genera of great apes or hominids, in the eighteenth century the lines of differentiation were erratic.8 On the one hand, all of the more hairy, human-like creatures were referred to as “orangutans” regardless of whether they originated in Africa or Southeast Asia, and on the other, their relation to humans—this time being prior to the theory of evolution—was uncertain. Apes inhabited the thickness of the line between nature and culture, yet less often closer to human than beast than vice versa.

All that argued for the orangutan’s humanity had to concede that at the very least, compared to the human, the orangutan was imperfect. In the words of American primatologist Robert Yerkes, by being “almost human,” apes were perceived to be less than human.9 There were, of course, other groups considered by Europeans to be imperfectly human as well, like indigenous people and slaves. The interplay of the ape’s human proximity and imperfectness extenuated the philosophical, scientific and juridical problems of the time. Could apes be “perfected”? Taken out of the forest, could they be made to work in fields and cities, even introduced into civilized life? Could they become the subject of laws and rights?

These questions started a debate that ebbed and flowed over the next 300 years. Contemporary attempts by animal rights activists to extend a form of human-like rights to apes—some of which have been spectacularly successful—are argued on the basis of similarity between the species; on apes’ anatomical, genetic and mental proximity to humans.10 In recent years, primatologists have successfully mapped traits and proven characteristics as complex as mental and emotional consciousness, self-awareness, compassion, causal and logical reasoning—previously thought to be uniquely human—as existing in these “almost human” creatures. Such similarity has allowed activists to use the vocabulary originally conceived to refer to violence inflicted by humans to humans, such as genocide, incarceration, concentration camps and torture, to describe the human treatment of animals. Within the animal rights debate apes were not the only target of activists, yet they functioned as emissaries in crossing the nature/culture divide; once awarded to apes—based on their proximity to humans— rights could be extended to mammals and other sentient beings—based on their proximity to apes.

Climate Change as Human Change

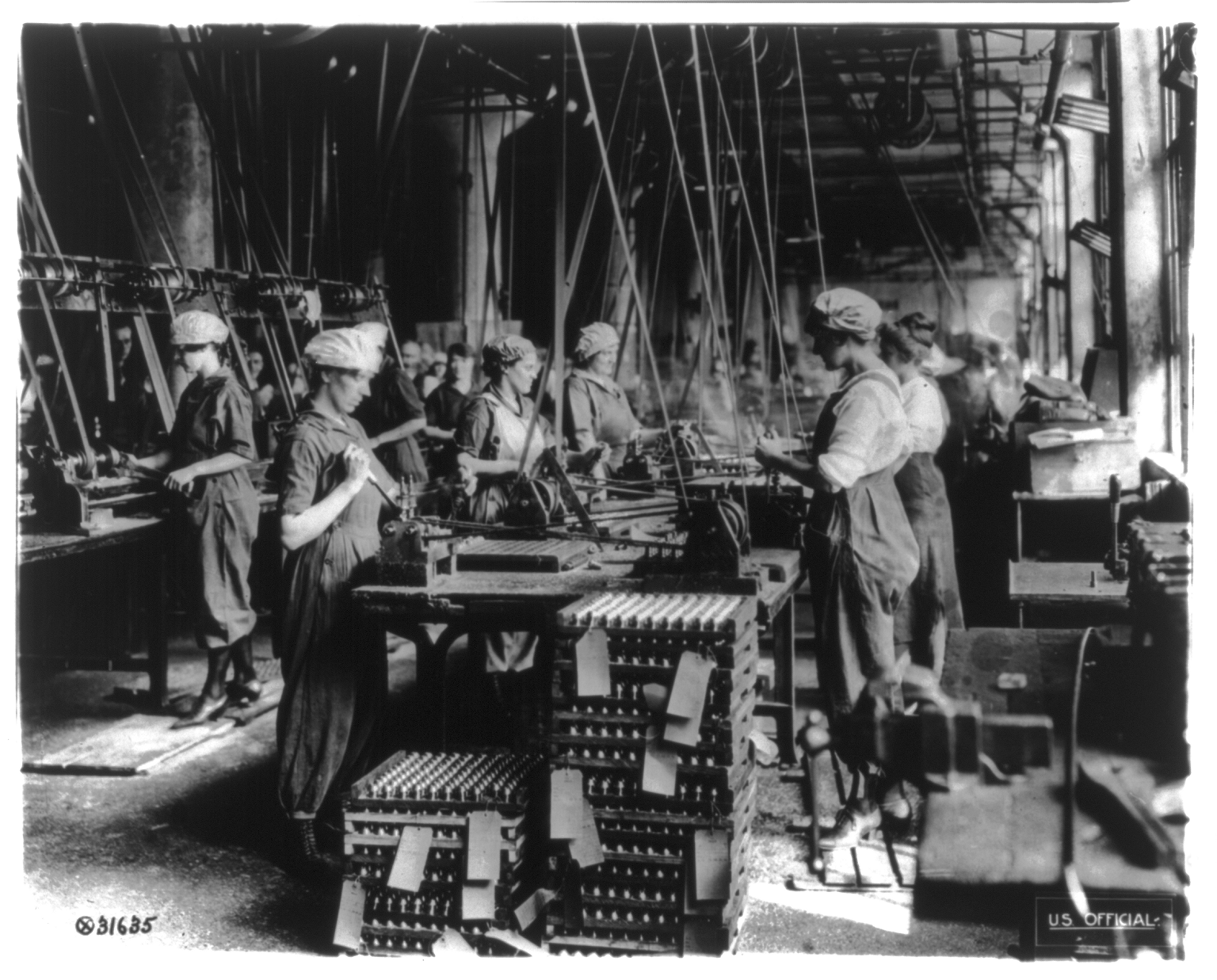

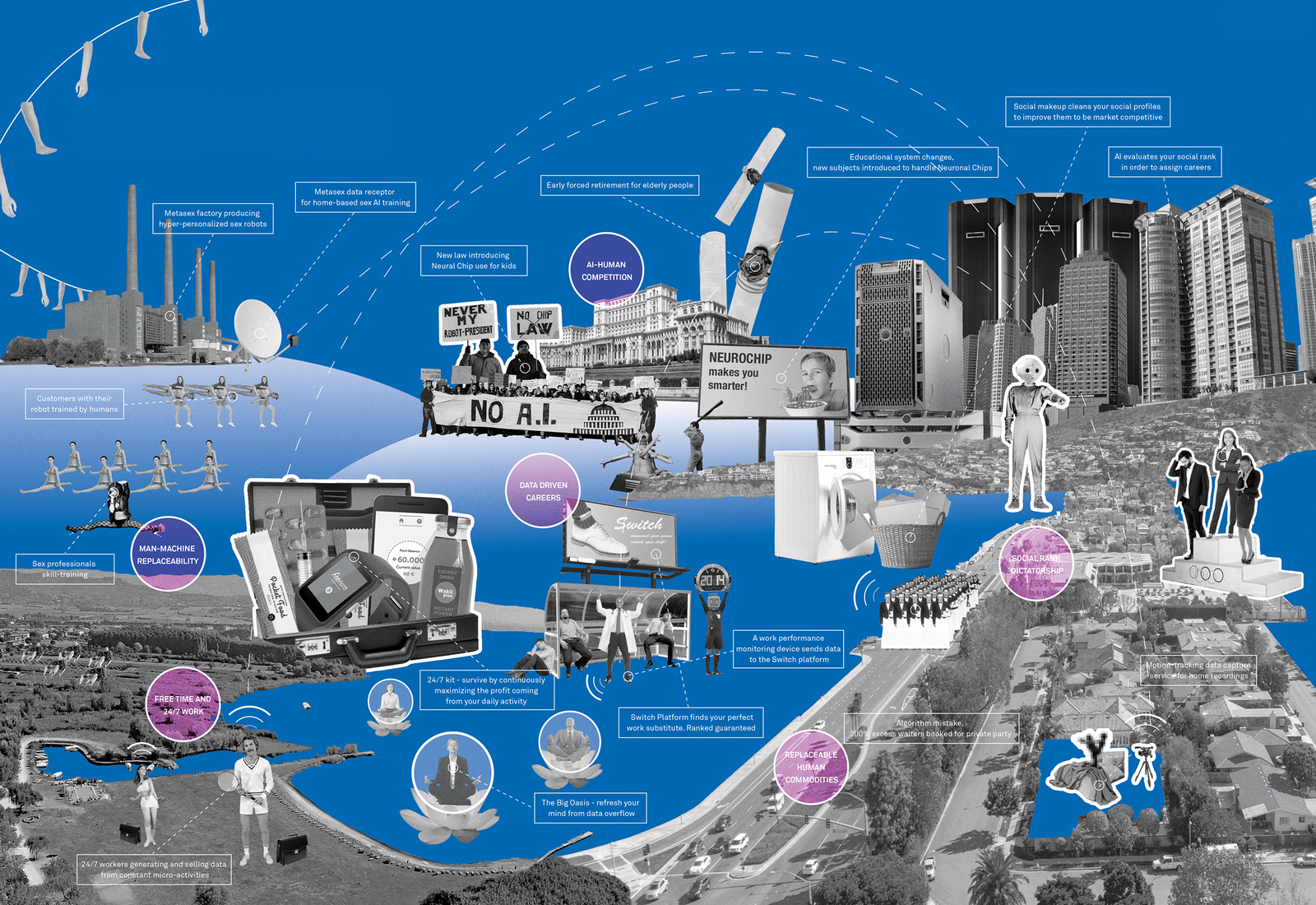

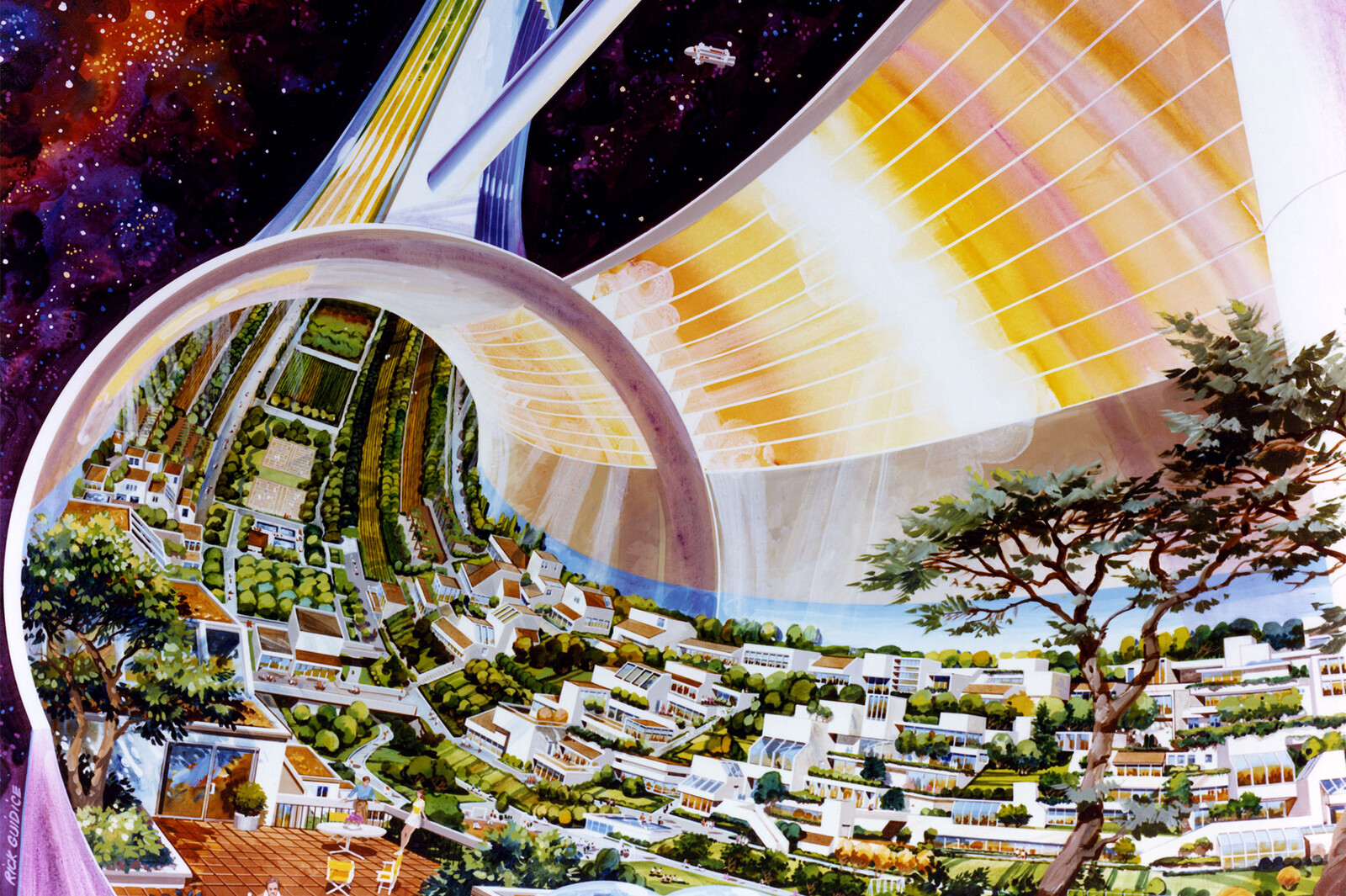

Even the most militant of today’s environmentalists and climate activists tend to hold a form of perception that has already been largely discarded in other contexts such as human rights and anti-war activism: climate change is regarded as the “collateral damage” of history, such as the unintended by-product of industrialization. Seen from the point of view of eighteenth century colonial history, however, climate change is an intentional project: colonial administrators did not only seek to take control, tame and mast the physical reality of newly discovered lands, but to engineer and change the environments, including their cyclical climate patterns. The aim was to, on the one hand, increase precipitation and cool environments in places too hot and dry such as the American west, Australia, and later, after WWI, in “the Orient,” and on the other, to reduce humidity in inhospitable tropical environments. The term “climate change” was born not with the recent discovery of the devastating effects of global warming but in the late eighteenth century as a potentially positive, and thus potentially positive, consequence to the human husbandry of nature. David Hume, Hugh Williamson, Thomas Jefferson and Noah Webster all held differing views about the human capacity—and the relative advantages—to effecting climate patterns across the expanding colonial frontier.11 While there were various techniques for affecting climate change such as draining of swamps, digging canals and constructing towns and cities, trees, practices of a- and de- forestation were most common. The American meteorologist James Espy, nicknamed the “Storm King,” for instance, believed that burning forests would create artificial clouds and irrigate deserts. Planting along desert thresholds, such as the twentieth century Zionist campaign to “make the desert bloom,” was conversely believed to reduce temperature and increase humidity. Despite the fact that an understanding of climate at the scale of the planet did not yet exist, small-scale changes were thought to be capable of causing not just local but long term change in climate cycle patterns. Once climate change was understood as a potential outcome of human action, the climate—like eventually the planet itself—came to be approached from a managerial, technocratic, and profit-oriented perspective as a design object; as a form of government over nature and man.

Some eighteenth-century thinkers not only believed in the capacity of man to induce changes in the climate, but also the inverse; in the power of the climate to determine changes in humans and their social and political structures. As Thomas Jefferson wrote in one of his more overtly racist paragraphs (as did many other contemporary writers), while the frequent variation of seasonal weather in more northern latitudes gave the necessity for constant adaptation, and thus more developed societies with a stronger work ethic, the tropical climate, in which he thought seasons were less distinct. encouraged laziness, promiscuity and was degenerative to society.12 From such a perspective, salvation—of both people and environments—was offered only by the redeeming force of labor. Idle forests had to turn into productive fields in the same way that “primitive peoples trapped in ape-like indolence” would find a route to civilization in the forced labor of slavery. Changes in the climate were believed to lead to changes in the human and vice versa: anthropogenic “climate change” meant environmental “human change.” Where the climate was to change, so was man.

Rousseau and the Orangutan

In a long footnote to his 1754 Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men Jean-Jacques Rousseau unexpectedly turns his attention to the orangutan. His hilarious descriptions of the ape are clearly influenced by travelers’ accounts from late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, in that they “fall upon elephants who come to graze in the places where they live and make them so uncomfortable with punches or blows with sticks that they force them to run away screaming.” While they are evidently cunning, Rousseau’s orangutans also perform all of the other things Europeans attributed to them at the time, including enjoying fire, cooking and burying their dead. Rousseau also mentions that the orangutan erects in the trees “a kind of roof which keeps them covered from the rain.”13 The perceived sense of discomfort—evidenced by this architecture—reveals a gap, an imperfect connection between the ape and its indigenous environment. Such a gap is typical of humans, but in the perception of the eighteenth century, an animals’ relation to its environment must be immediate and perfect. The orangutans were, for Rousseau, human beings at the beginning of the process of civilization, and while never explicitly interpreted as such, the architecture of the orangutan could be seen as one of the first steps in such a process (or, in fact, the first slip on a slippery slope towards it, considering Rousseau’s well known ambivalence to civilization).

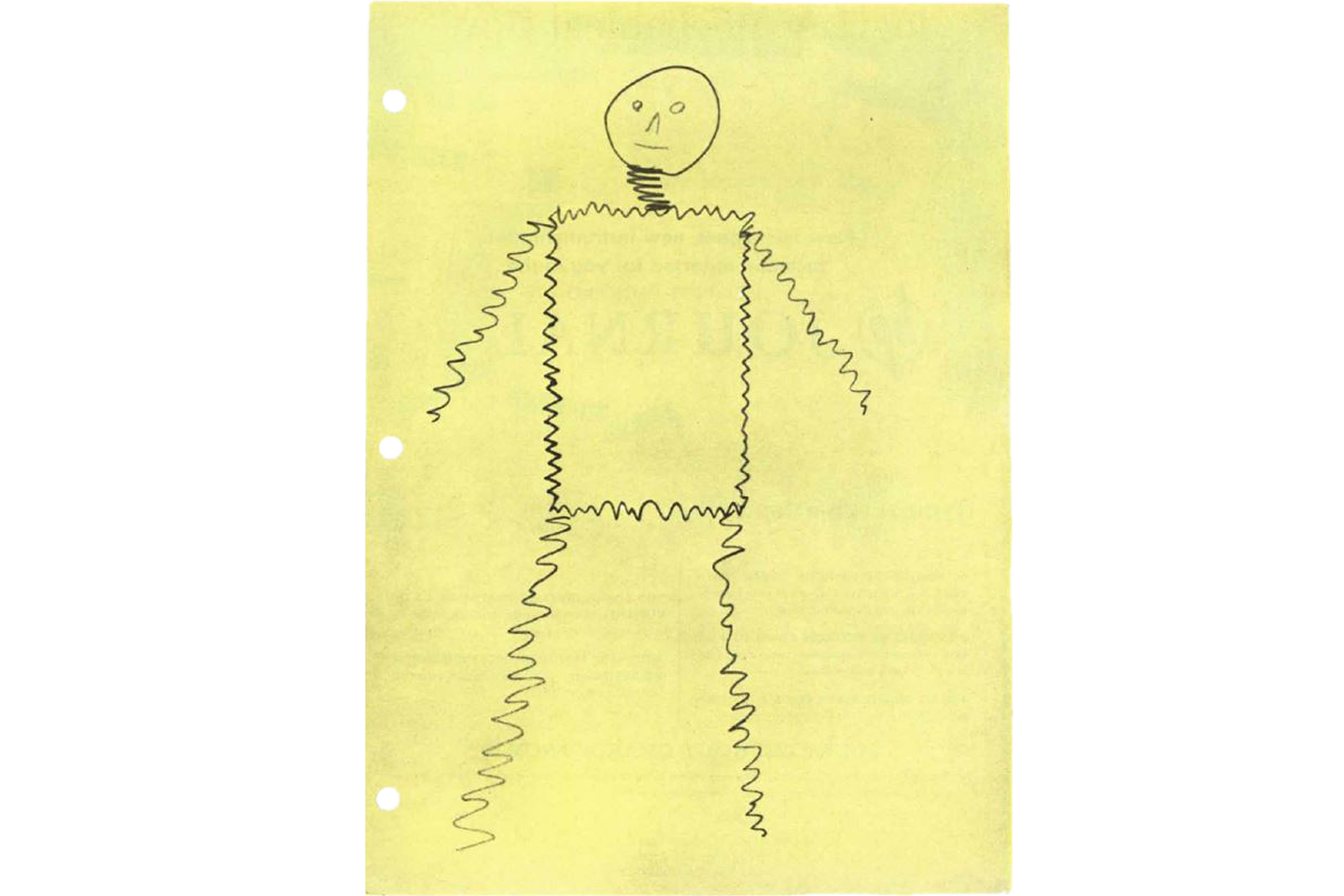

Unlike most of his contemporary writers, Rousseau’s argument for the humanity of the orangutan was not based on physical and behavioral resemblance, and he did not celebrate the orangutan as an archetypical “noble savage,” but rather that the ape shared a certain elasticity with humans; the capacity to learn, improve and perfect one’s self to make a “civil man above his original state.”14 Yet if the threshold of the human is indeed elastic, it is elastic in all directions: once you can “become human” you could also, depending on conditions, possibility, and of course value system, slide back across the border again and “become animal.” 15 The model Rousseau found for crossing back over the line of the human were several reports of “wild childrens,” abandoned in the forest beyond the outlying villages of Europe who managed to survive by “becoming animals.” Rousseau mentioned a report about one such enfant sauvage found in 1694 in particular: the child “did not give any sign of reason, walked on this hands and legs, had no language, and formed sounds which bore no resemblance to those of a man,” yet was reportedly taught to speak quickly and readied “to (re)enter human society.” 16

The Dehumanization of Nature

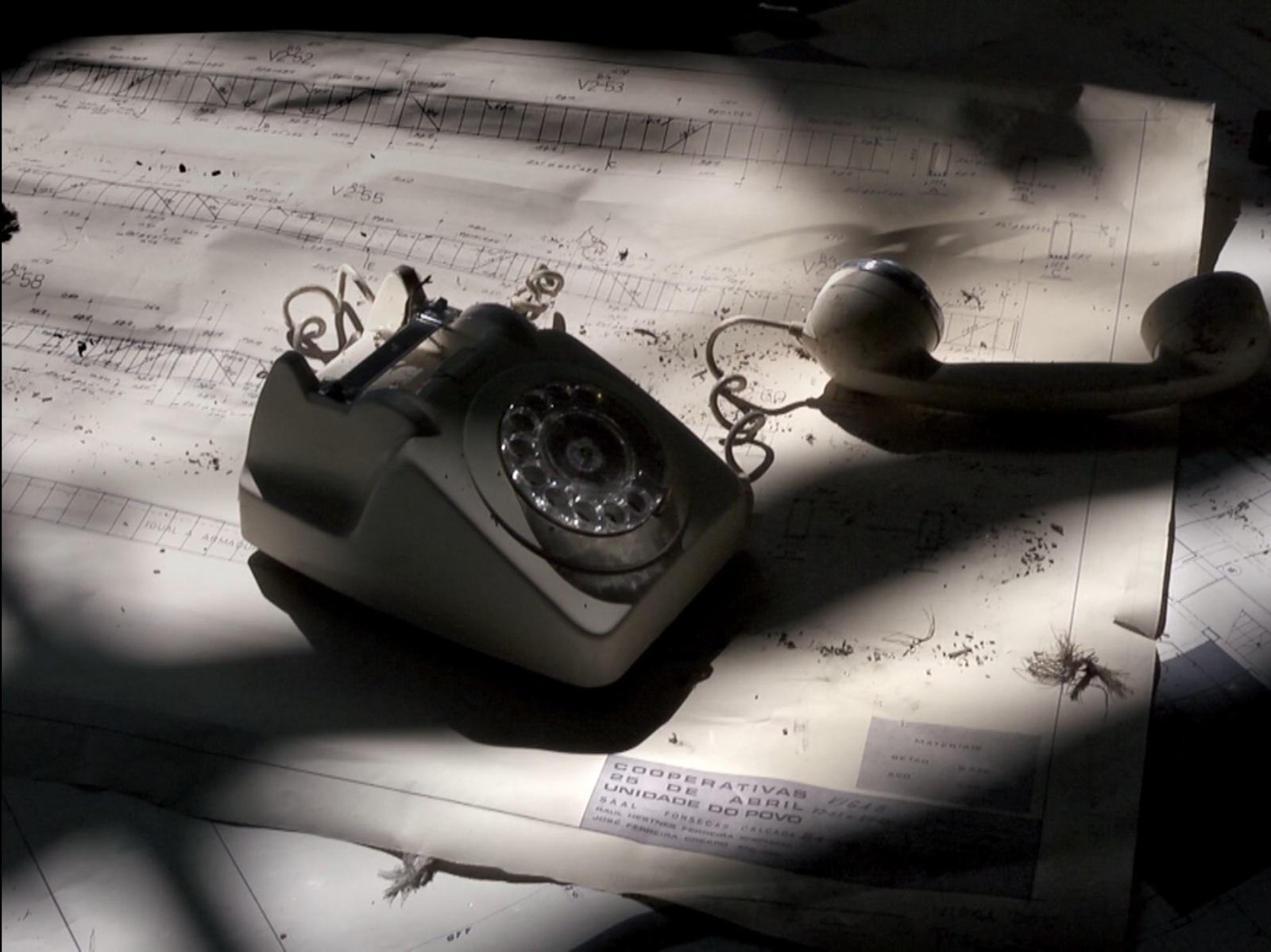

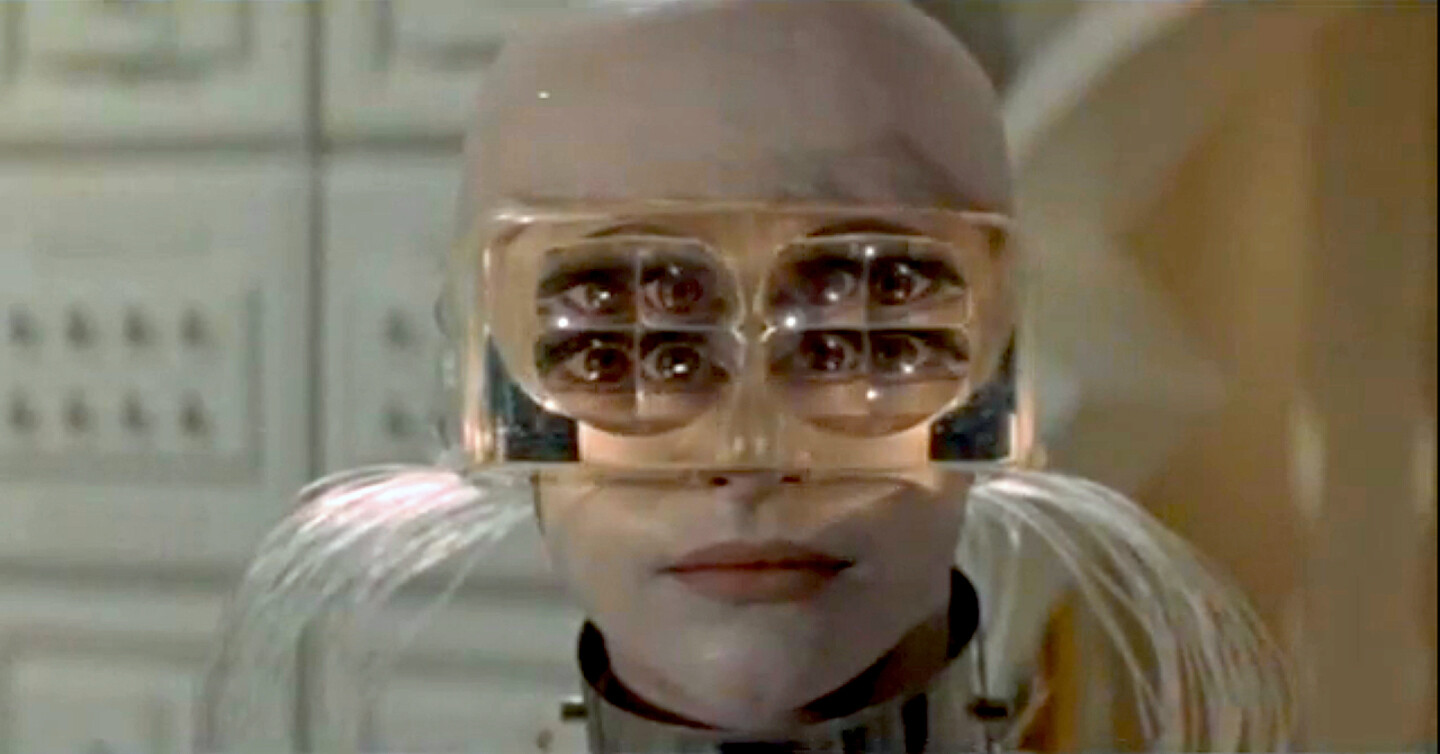

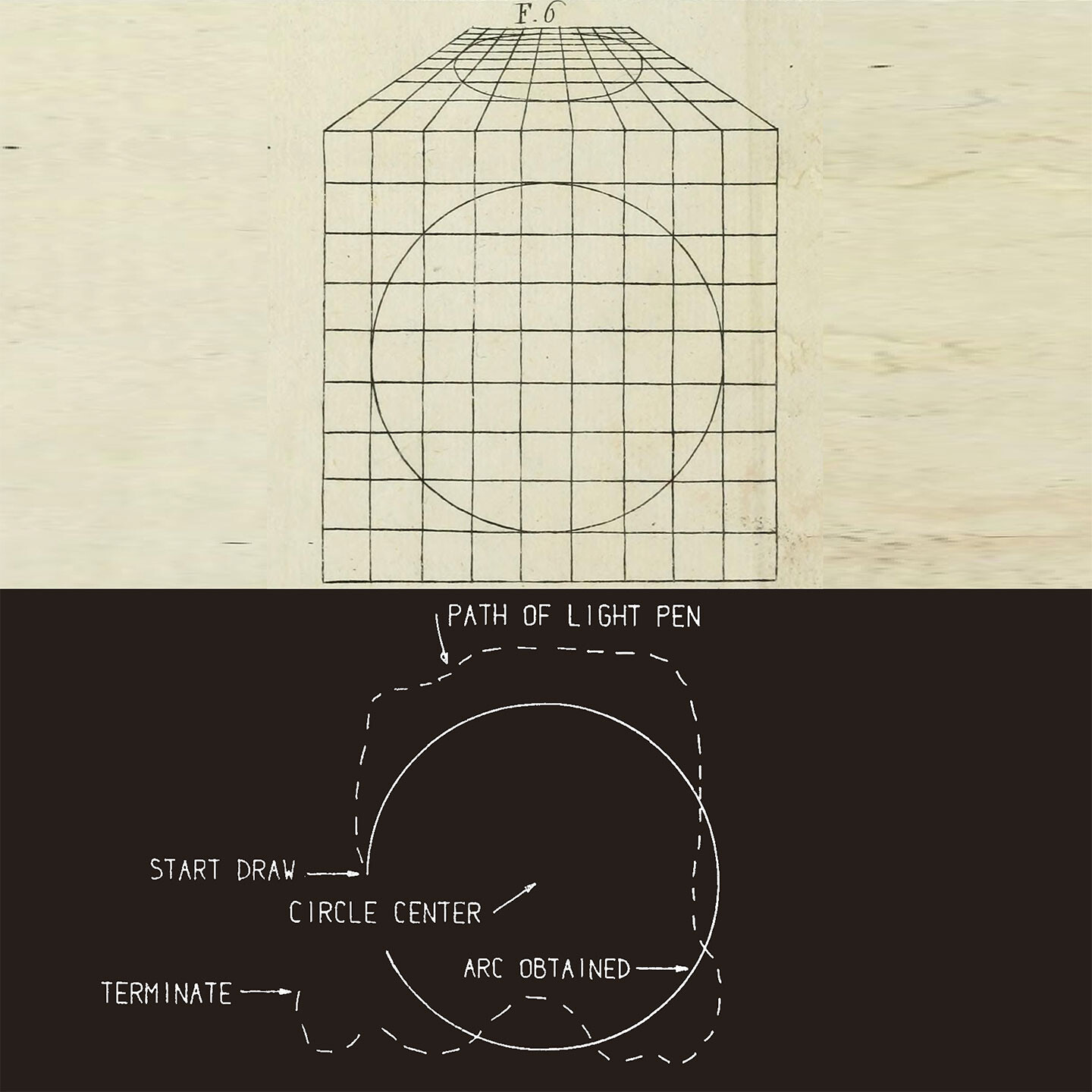

Rousseau wrote at a time when barely half a dozen great apes had been scientifically examined. In 1777, two decades after Rousseau’s Discourse was published, a so called “orangutan war” erupted in the Netherlands. It started when a young ape brought from Borneo died. “War” is perhaps an overstatement, but the incident did involve a sharp exchange between two groups rallying around opposing figures: a taxidermist named Arnout Vosmaer, who had begun to prepare the body of the dead orangutan for display (in an upright position), and anatomist Petrus Camper, who wanted to dissect it for scientific purposes. After Camper’s better connections in the Dutch court were sufficient to get hold of the remains—which were already partly prepared for stuffing—his skeletal analysis identified that, contrary to contemporary pictorial representations, walking upright was anatomically impossible.

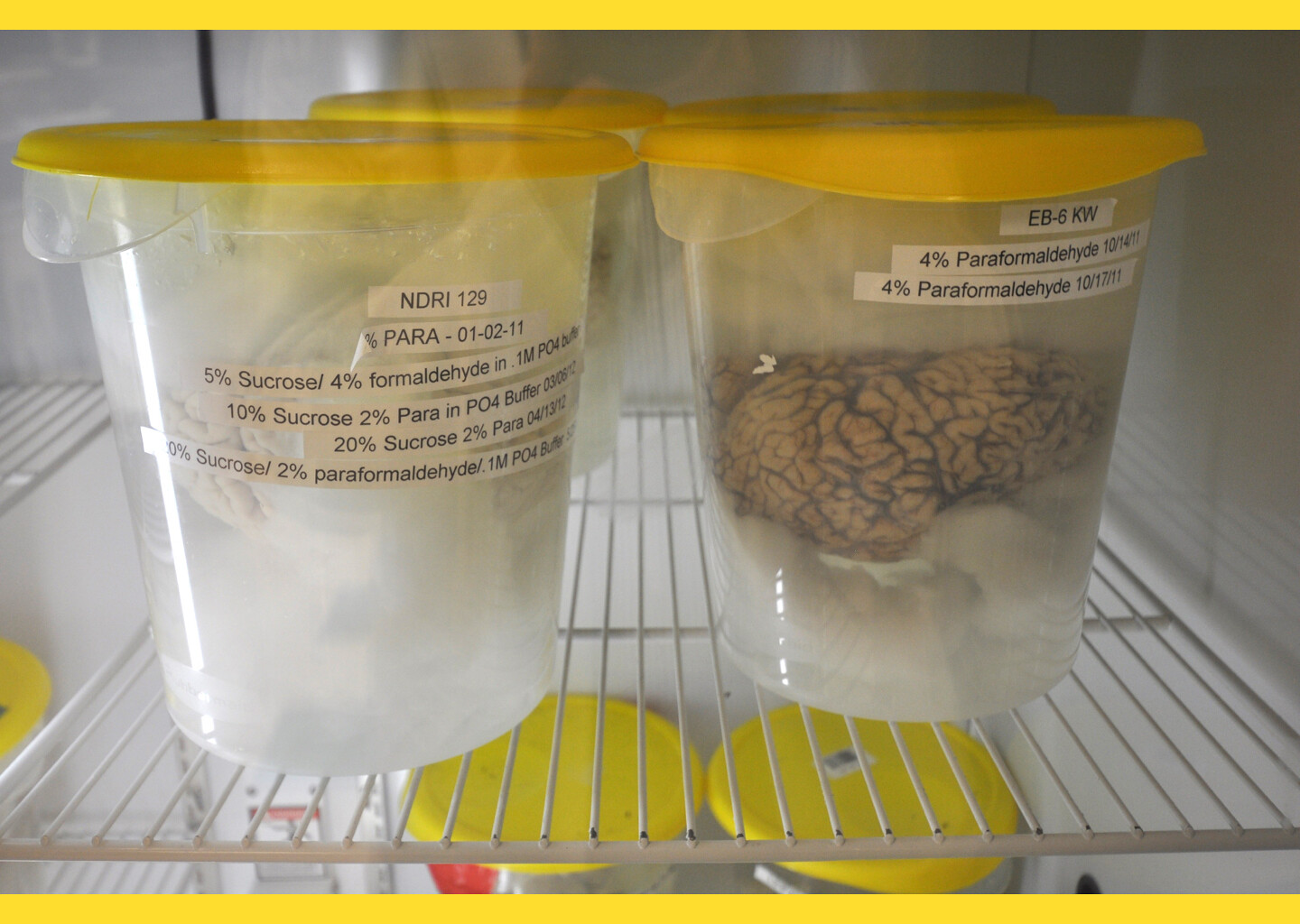

Yet beyond posture, the crucial element Camper searched for was the human source of language, which in the eighteenth century was thought to be the voice.17 Camper dissected, opened up and carefully documented the ape’s throat, and finally proclaimed the orangutan’s larynx—the organ housing the vocal cords essential for sound production and phonation—foreclosed to the possibility of anything resembling human speech.18 Without a humanlike larynx, he concluded that the orangutan could not become human. The threshold between man and animal, previously blurry and elastic, had thus become fixed in a position it stood for the following centuries. The dehumanization of the ape was one step taken among many during the turn of the nineteenth century away from the anthropocentric perspective of nature.

The issue Camper believed to have settled still haunts debates around animal rights. In the second half of the 20th century, the orangutan, like other apes, started speaking in human language (again!) using non-vocal sign, hand, and pictorial languages. The wealth of mental expression that sprung out supported right claims based on orangutans’ proximity to humans. The orang-utan has in the forest, of course, its own non-human language.

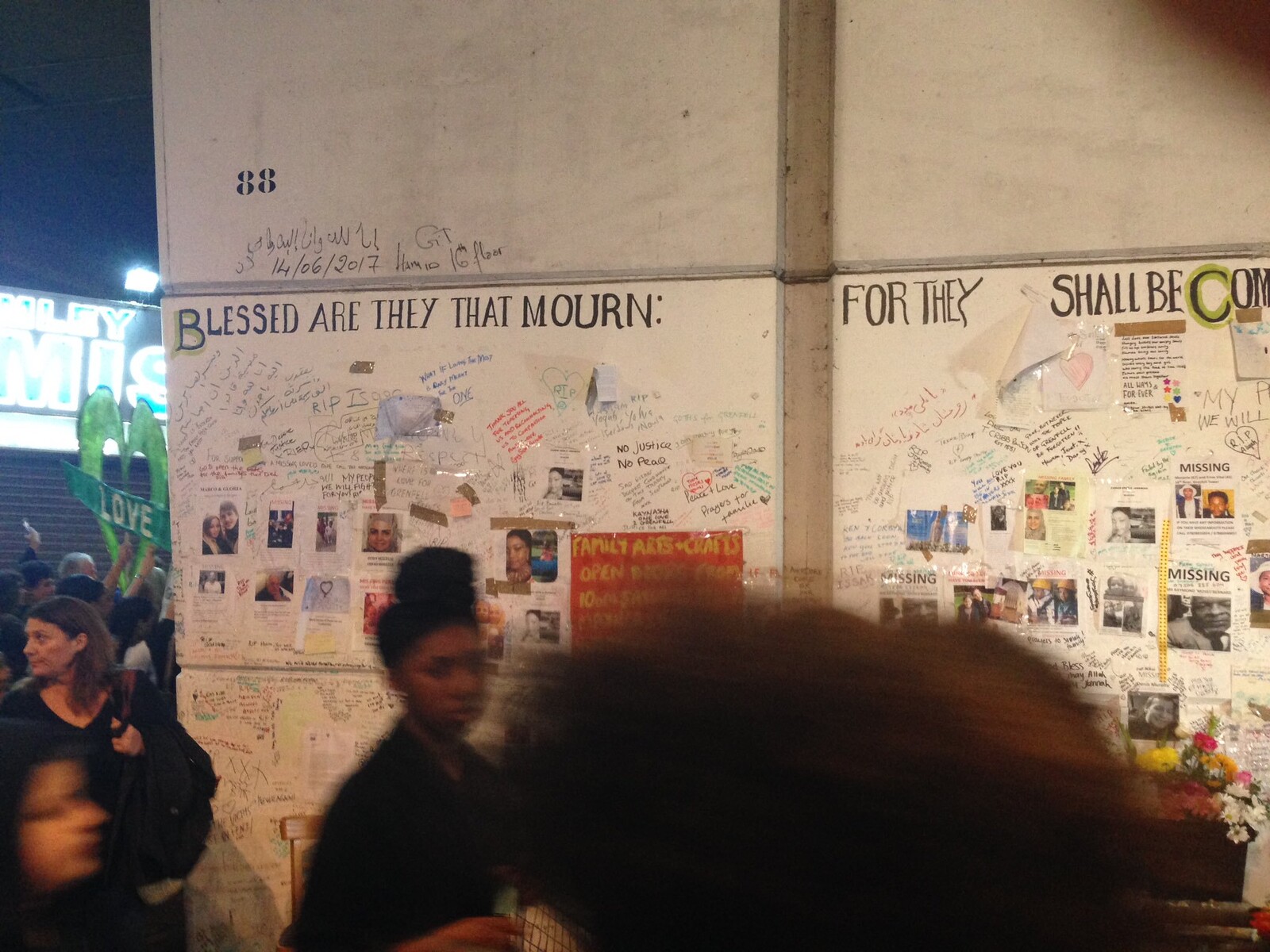

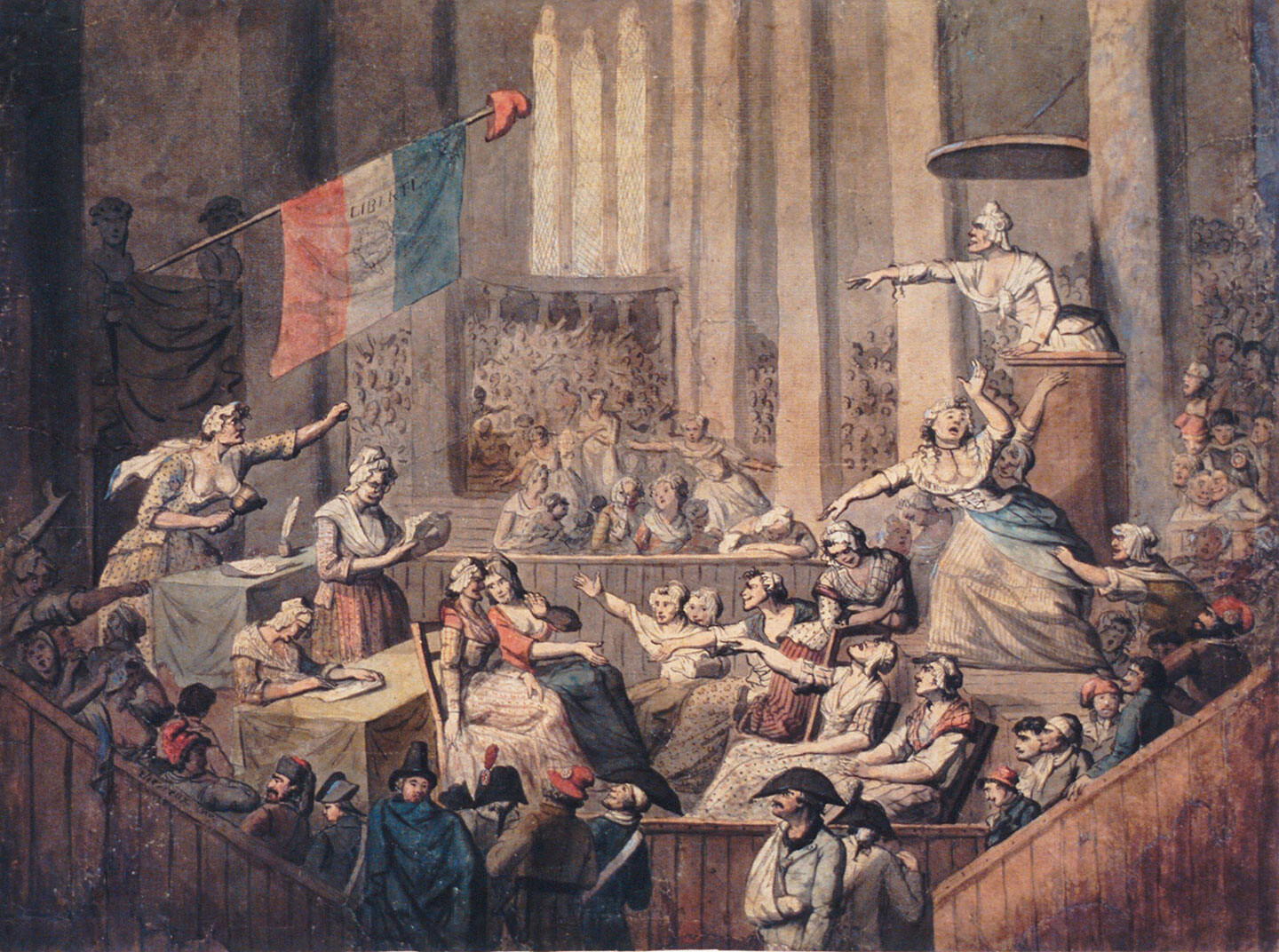

Camper’s exclusion of the orangutan from humanity took place at an important fold in history: the destruction of the Ancien Regime, a period bracketed by two important markers by which the ideology of humanism was ratified—the American Declaration of Independence and France’s revolutionary assembly’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen—and the beginning of the geological era of the anthropocene. (The era of human could seemingly only begin once the question of what is a human was decided.)19 These declarations had an ambivalent relation to the question of who or what is a human. On the one hand, both relied on a conception of humanity that is apparently clear and unchangeable—all men are “born and remain” what they are, their rights “inalienable” and “self evident” rather than, for example, having to evolve into rights (and out of them).20 Taken by their word, the declarations’ definition of the human seems static and eternal. However as Thomas Keenan, following historian Lynn Hunt, shows, the declarations’ ongoing dissemination and influence was precisely due to the fact that they did not define or fix what they meant by “human.”21 Yet its meaning in practice tended to exclude foreigners, landless, slaves and women. In these cases the biological threshold of the human obviously did not overlap with the effective threshold of rights or the law, which the ongoing struggle for human rights aims to make overlap.

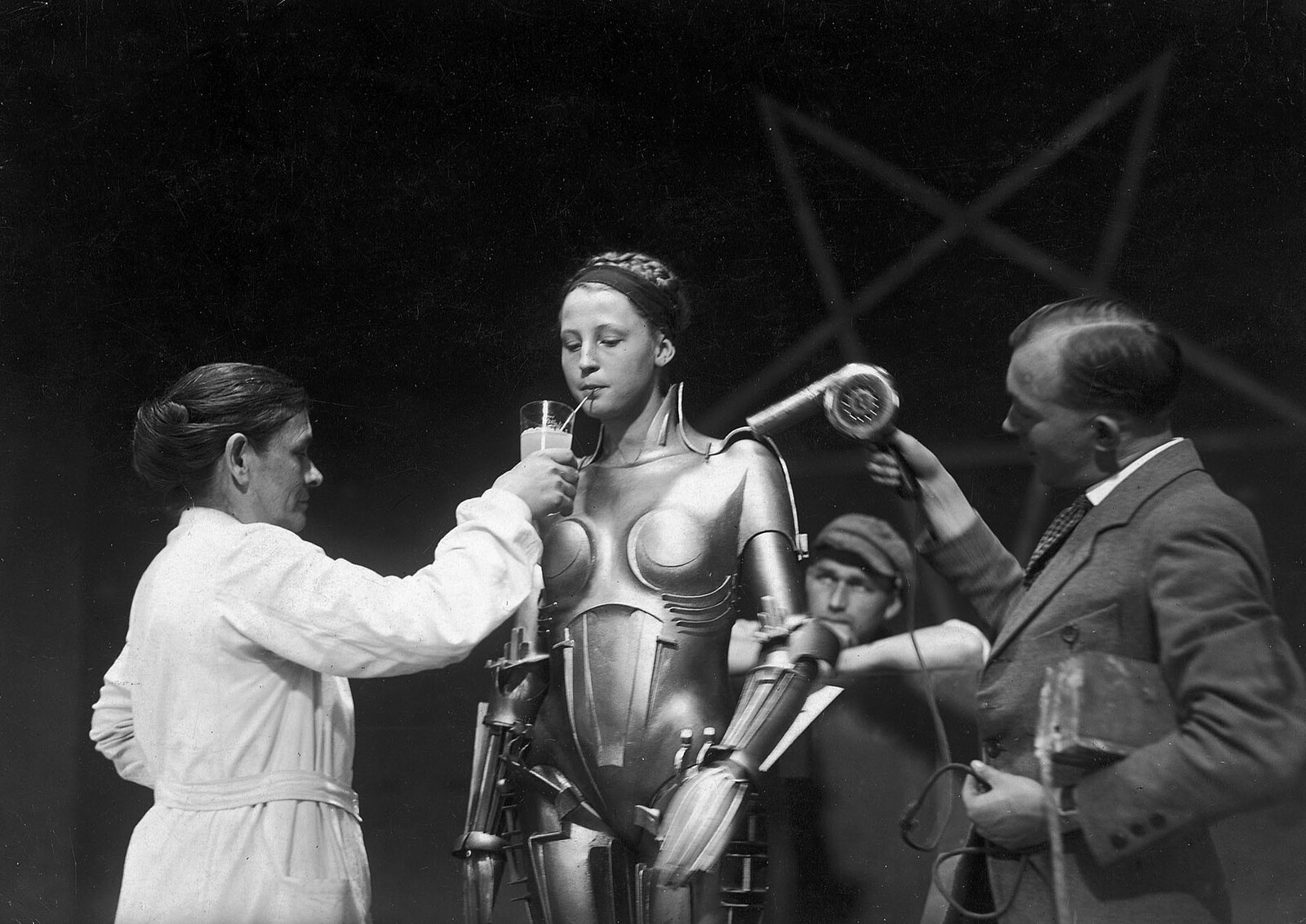

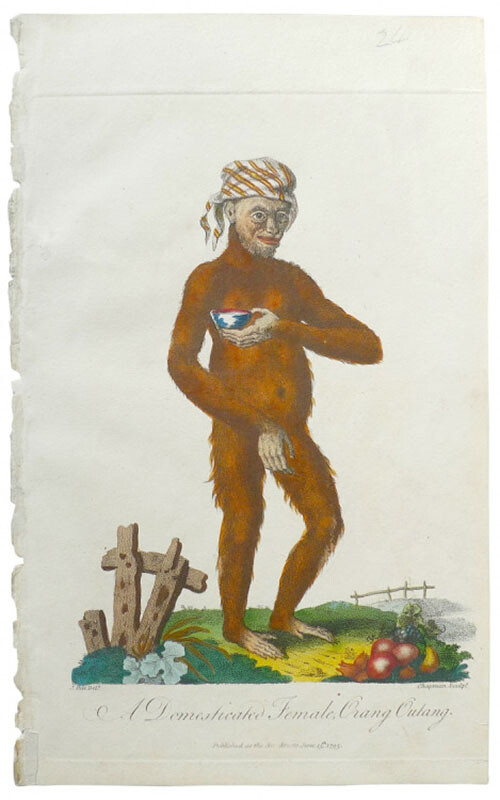

“Domesticated Female Orangutan” depicted as a slave in this 1795 illustration. “She seemed to have a sense of what was required of her, even before the words were spoke; and her chief emulation was that of being more active and adroit than any servant about the house.” Ebenezer Sibly as quoted in Cribb, Gilbert, and Tiffin’s Wild Man from Borneo: A Cultural History of the Orangutan (2014). Orantuans were perceived as alternative to slaves, less rebellious and more loyal.

Equality beyond the perceived biological threshold of the human is however a matter entirely distinct from equality between humans. Moreover, human rights claims are often articulated by reinforcing this very border, by marking the distinction between humans and animals. Many human rights claimants protest that they are human, not animals; that is to say, that they are on the side of the line where rights should be in force, but still treated as if they were on the other, like dogs, insects, apes or sheep. Such a threshold also tends to exist in the eyes of perpetrators of violence, for whom actions are often justified by the “animalization” of the stranger, the enemy, the terrorist, the indigenous or the barbarian. In the nineteenth century, pro-slavery politicians were, according to Cribb, Gilbert and Tiffin, more inclined to accept the possible humanness of the orangutan, for if the ape was part of humanity, humanity could more justifiably be stratified into a hierarchy of races, with white man on top, the orangutan at the bottom, and the pigmy, blacks and other peoples in between. These advocates of slavery also recalled a Javanese belief that the orangutan was able to speak but chose not to do so for fear of being put to work, taken as slave or made to pay taxes. Ape-like characteristics have been applied to indigenous peoples throughout history in order to justify slavery as an act of “civilization” and redemption. Abolitionists thus sought to keep the threshold of humanity tighter, and humanity smaller. Yet if human rights claims demand to be remedied by the “humanization” of people who are already human, what can remedy the violation of non-human rights?

Orangutan Rights (Notes for the Next Chapter)

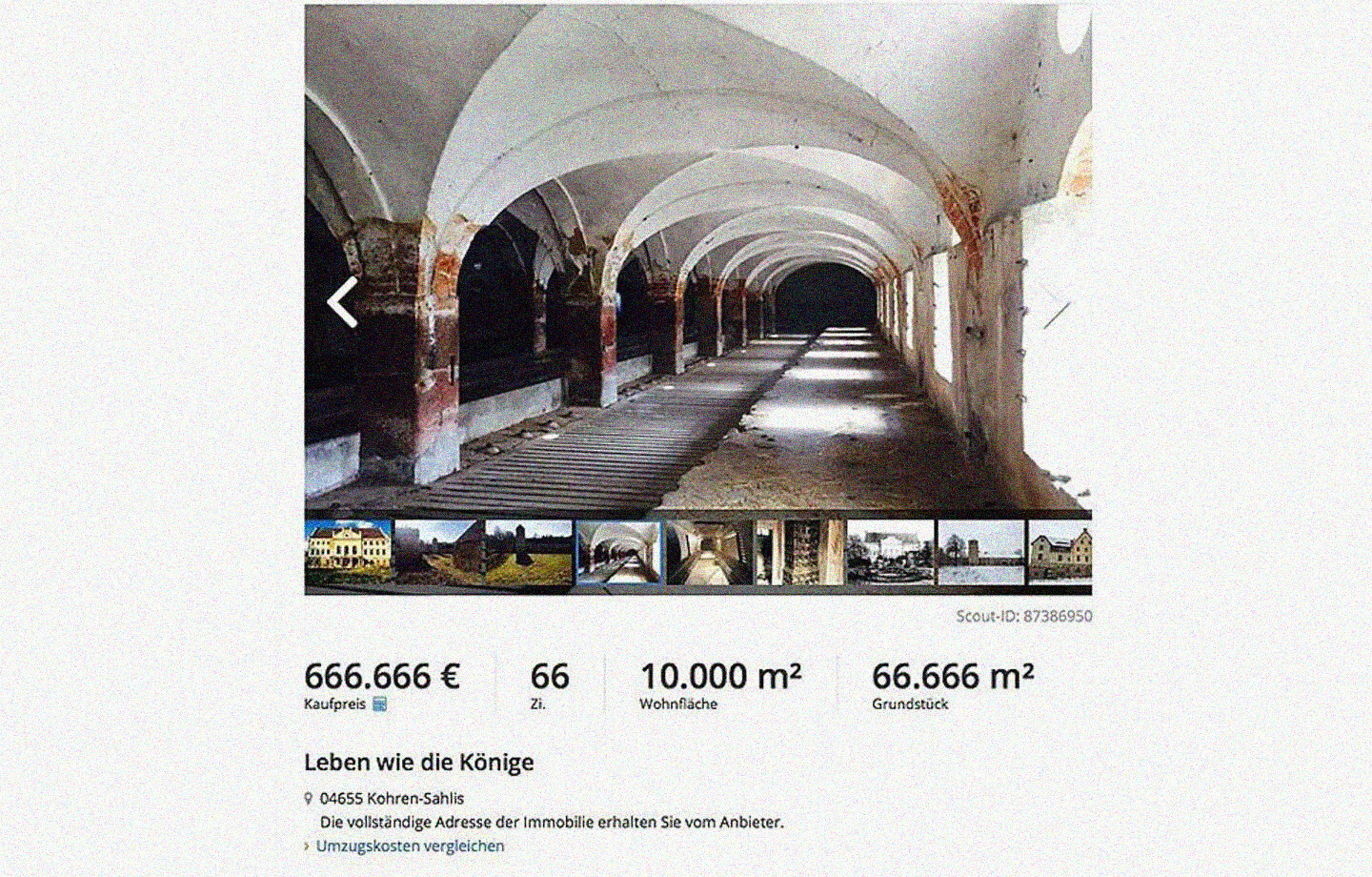

Given that apes, like orangutans, were considered to be part of a fuzzy definition of humanity until being “expelled” at the end of the eighteenth century, current attempts at granting apes legal personhood and some form of non-human rights do not amount to a simple admission into an expanded humanity, but rather re-admission. Much has changed, however, in the intervening 240 years: the human population has grown sevenfold, undertaken colonialist, imperialist and genocidal projects, and destroyed the Earth’s ecosystem to the extent that it has now critically endangered its own survival. In so doing, humans have almost completely wiped out the ape population and concentrated the remaining survivors in tiny islands of forest. If, as some proponents of rights seem to suggest, the orangutan could want, would it want to join our species? Maybe. Maybe it would have no choice. Yet this reunion could take place along different terms than those of the perpetrators. If survival in the era of global warming indeed requires humans to consider themselves as belonging to one biological species amongst others, as Dipesh Chakrabarty suggests, the threshold of the human stands to be crossed in the opposite direction, away from homo sapien in a process of becoming-hominid. We would also, then, have to invert the problem of rights: rather than demand individual human rights for apes, we would rather need to seek something resembling “orangutan rights” for humans.22

This text is a kind of epilogue to Hila Peleg’s and Anselm Franke’s ‘Ape Culture’ at the HKW and a prologue to a collaboration between Forensic Architecture and FIBAR: Baltasar Garzon. This text is greatly indebted to conversations with Paulo Tavares, Thomas Keenan, Eduardo Cadava, Mauricio Corbalan, Pio Torroja, Bernhard Siegert, the IKKM fellows program in Weimar, and Giorgio Agamben.

Jed O. Kaplan, Kristen M. Krumhardt, Niklaus Zimmermann, “The prehistoric and preindustrial deforestation of Europe,” Quaternary Science Reviews, no. 28 (2009): 3016–3034.

For more on the reading of this image see Giorgio Agamben, Stasis, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015).

Paulo Tavares, On the Ruins of Amazonia, (London: Verso, forthcoming).

Haraway, Primate Visions, (New York and London: Routledge 1989), 10.

Robert Cribb, Helen Gilbert, and Helen Tiffin, Wild Man from Borneo: A Cultural History of the Orangutan, (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2014), 57.

Wild Man from Borneo, opcit, 32.

Giorgio Agamben, The Open, Man and Animal, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), 24.

Both Pan (chimpanzee and bonobo) and Gorilla (gorilla) are indigenous to the forests of central Africa. Pongo (orangutan) are indigenous to the forests of Sumatra and Borneo, and Homo, which has grown indigenous to the rest of the world.

Robert M. Yerkes, Almost Human, (New York and London: Century Co., 1925); Wild Man from Borneo, opcit, 46

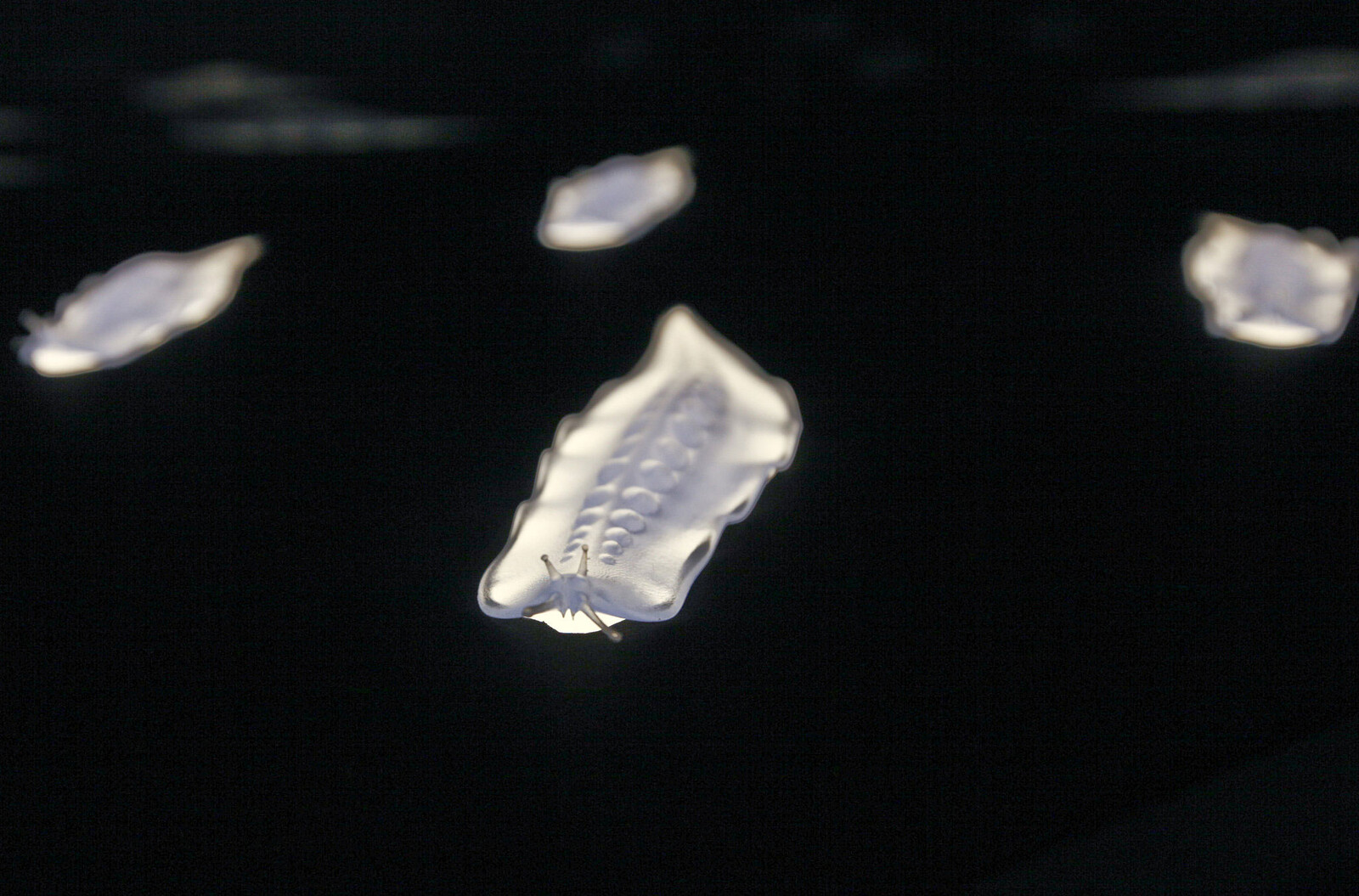

In Forensic Architecture’s and m7red project for the 2016 Istanbul Design Biennial—a project lead by Paulo Tavares, Samaneh Moafi, Christina Varvia, Mauricio Corbalan, Pio Torroja and Nabil Ahmed, and undertaken in cooperation with the office of Baltasar Garzon—we followed a case in which the female oranguatan “Sandra” pictured at the beginning of this essay was given something resembling human rights in Argentina.

Hugh Williamson was the first to have used the term “change of climate.” Williamson also proposed a programmatic change of climate by landscape modifications. Thomas Jefferson wrote: “In order then that we may be able to form an estimate of the heat of any country, we must not only consider the latitude of the place, but also the face and situation of the country, and the winds which generally prevail there, if any of these should alter, the climate must also be changed. The face of the country may be altered by cultivation, and a transient view of the general cause of winds will convince us, that their course may also be changed.” Eduardo Cadava, Emerson and the Climates of History, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997); Hugh Williamson, “An Attempt to Account for a Change in Climate which has been Observed in the Middle Colonies of North America,” read before the Society (American Philosophical Society), August 17, 1770; Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (Philadelphia: Richard and Hall, 1785), 273. Noah Webster provided a rebuttal. Noah Webster, “On the Supposed Change in the Temperature of Winter,” The Connecticut Academy of Arts and Science, 1810. More the Webster/Jefferson debate see: Joshua Kendall, “America’s First Great Global Warming Debate”, smithsonian.com, July 14, 2011. Nineteenth century forest polices were based on “dessicationist” (extreme dryness) beliefs that deforestation caused local, regional and even continental drought. Note that none of these theories thought of the planet as a whole. J.R. Fleming, Historical Perspectives on Climate Change, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998); Richard Grove, Ecology, Climate, and Empire (Cambridge: White Horse Press, 1997).

Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia. opcit. A discussion of this issue exists in Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Jennifer Burton, Call and Response: Key Debates in African American Studies (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011), 17–24; see also Richard Grove, Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600-1860, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 163–168.

Today we know that these tree-top structures are used differently, that they are neither roofs for rain, but rather floors for nests, nor luxury, but necessity as a form of protection from predators.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, trans. Donald A. Cress (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1754/1992), 44.

Gilles Deleuze and Felíx Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1980/1987), 232–309.

Ibid., Rousseau.

Wild Man from Borneo, opcit, 43

Wild Man from Borneo, opcit, 43

One can also look at the same issue differently: The idea of “human exceptionalism” that saw humans uniquely distinct from animals, is echoed in the idea of the anthropocene, with exceptionalism this time articulated not as heroes but as villain-gods, alone in their ability to transform the material composition of the planet. The term “Anthropocene,” coined in the early 1980s by Eugene Stoermer, was popularized by Paul Crutzen in 2000. Crutzen proposed the emergence of the steam engine as the historical marker. Since 2008, The Anthropocene Working Group has proposed the scientific adoption and formal ratification of the Anthropocene epoch, the first step of which took place last month. Damian Carrington, “The Anthropocene epoch: scientists declare dawn of human-influenced age,” The Guardian, 29 August 2016 →.

Bernhardt Seigert, in a seminar at the IKKM in Weimar this spring, speculated that the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and the exclusion of the orangutan from humanity might be related in other ways too. Text forthcoming.

Thomas Keenan, “Claiming Human Rights,” in Thinking Out Loud Lectures (Western Sydney University, April 2016). Lynn Hunt, Inventing Human Rights (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008).

Dipesh Chakrabarty & Eyal Weizman, Forum, Dictionary of Now #2, Apr 11, 2016 →; Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom At The End of the World: On The Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, (Princeton: Princeton Press, 2015).

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.