Nick Axel Your practice, Snøhetta, has for the past thirty years pioneered questions of sustainability and problematized ecological challenges facing the building industry. But your Harvard HouseZero project seems to be quite unique in your portfolio. How would you describe it?

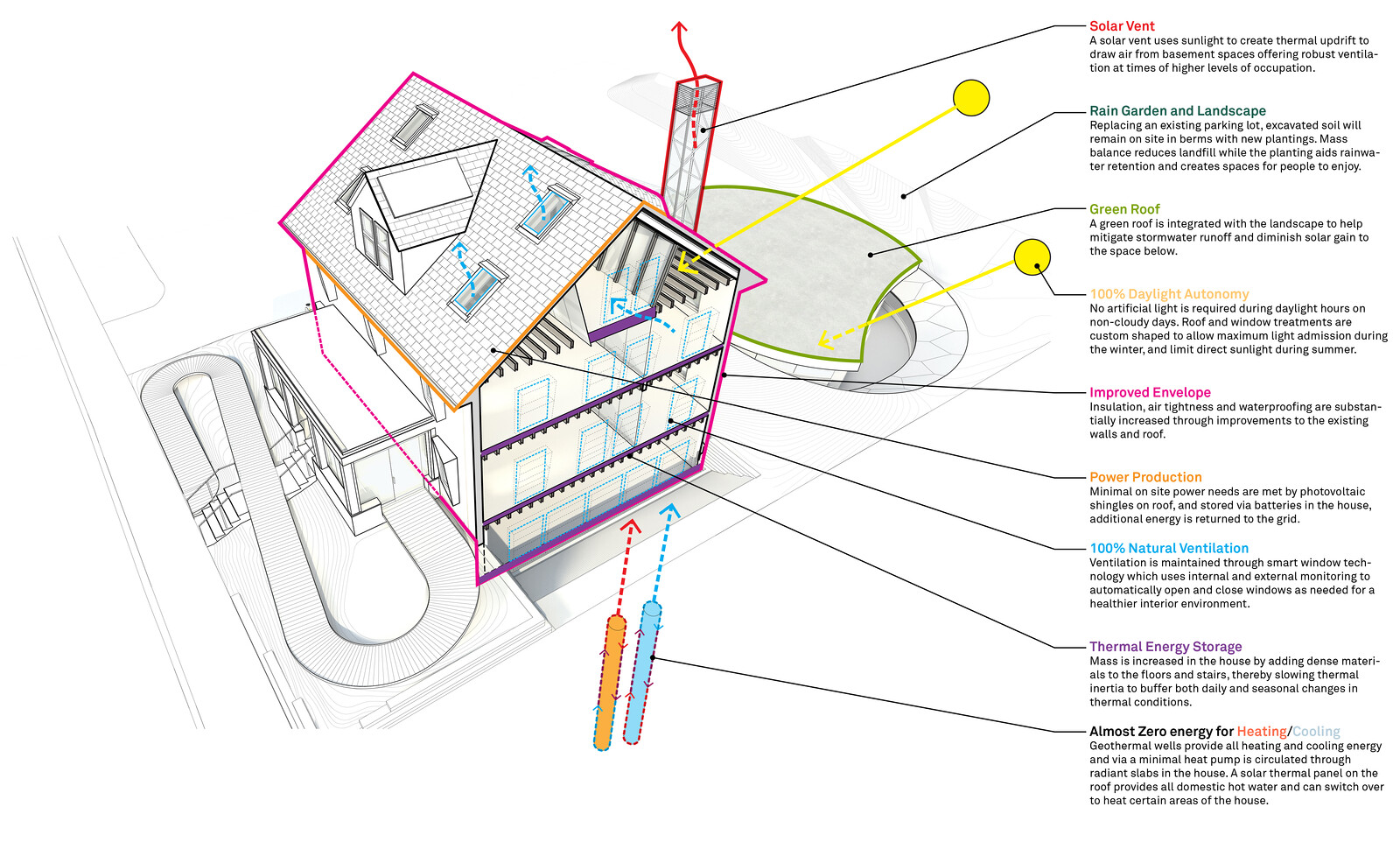

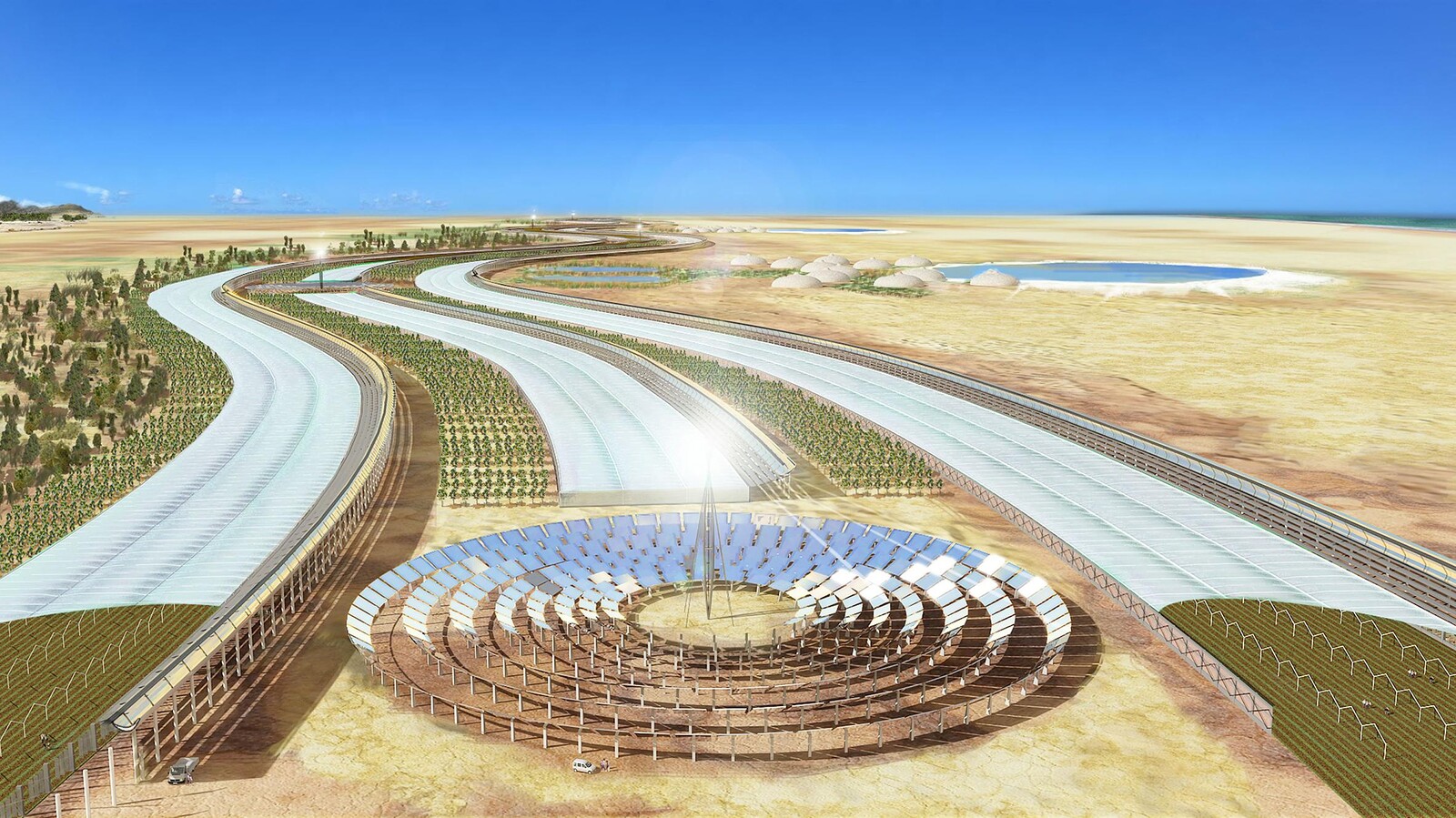

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen Our Harvard HouseZero project is part of our wider ambition of learning how to design architecture in such a way that it doesn’t use energy. HouseZero is, first and foremost, a set of architectural interventions into an existing type of building common to the United States: a wooden detached dwelling from the turn of the twentieth century. Alongside this is a sensor network and computational system that analyzes and reconfigures the energy dynamics of the house.

NA Does using computation—which we know to be energy intensive—to reduce the energy demand of buildings not defeat the purpose?

KTT It depends on how you look at it. But the question points to one of the great cognitive dissonances of our time: needing to do one thing that might not be so good in order to do something else that is.

NA The ends justifying the means?

KTT Well, I do think we’ve lost sight of the big picture, but regardless, it’s not as simple as “good ends justify bad means.” It’s much more complicated than that. It’s not bad against good; it’s good against good. Take, for instance, the debate around windmills. Producing clean energy is a good thing, right? The windmills we have are only becoming more efficient, and we’re only getting better at knowing where best to place them. But preserving nature is a good thing too, so nature preservationists often object and prevent windmill projects from being realized. Another example: the Green Party in Oslo recently cut down trees in order to facilitate biking in the city. Trees are good, but so is biking. One of the biggest dilemmas I can see for the future is not deciding which priority is right and which one is wrong, but putting them in sequence, one after the other, and understanding the effects they have on each other. In this sense, HouseZero is a prototype, a way to develop a base of knowledge about how different architectural elements interrelate with each other, but its goal is to scale up.

NA The American suburban home is something already at scale, and there’s a host of institutions that buttress it, such as insurance, mortgages, tax breaks, etc. The suburban home is a vehicle, a medium into which these interventions could theoretically could slip into.

KTT That’s what we hope for. But the project needs to prove its right of existence first.

NA What would it mean to prove that? And what role does computation play?

KTT The projects starts out by accepting the fact that if we are to use less, or even no energy, our habits and forms of inhabitation will need to change in certain ways too. For instance, instead of the typically stable internal temperature of twenty-one or twenty-two degrees Celsius, internal temperatures in HouseZero fluctuate between eighteen and twenty-six degrees. Not keeping the temperature of the whole house to a single stable figure requires much less energy to be used. But because it’s allowing for a higher degree of thermal discomfort, it’s important that the new limits are maintained; that temperatures don’t drop to fifteen degrees or rise to thirty. A lot of complex information and elements need to work in tandem to make sure that doesn’t happen, and working with large amounts of live environmental data in real-time is crucial for in that.

NA What is the design object here? Is it the solar chimney, or is it a way of understanding how solar energy gain works in turn-of-the-century wooden houses in the United States?

KTT Both. There are important things to learn about the performance of singular elements, but just because it works in one place doesn’t guarantee it’ll work anywhere else. You can’t even know if something that works in one house will work in the house next door, not to mention in a completely different climate. There is not one solution. Constant analysis and adaptation is essential.

NA Can you explain what you mean by the word “zero” in the project title? What does it mean for a building to use zero energy?

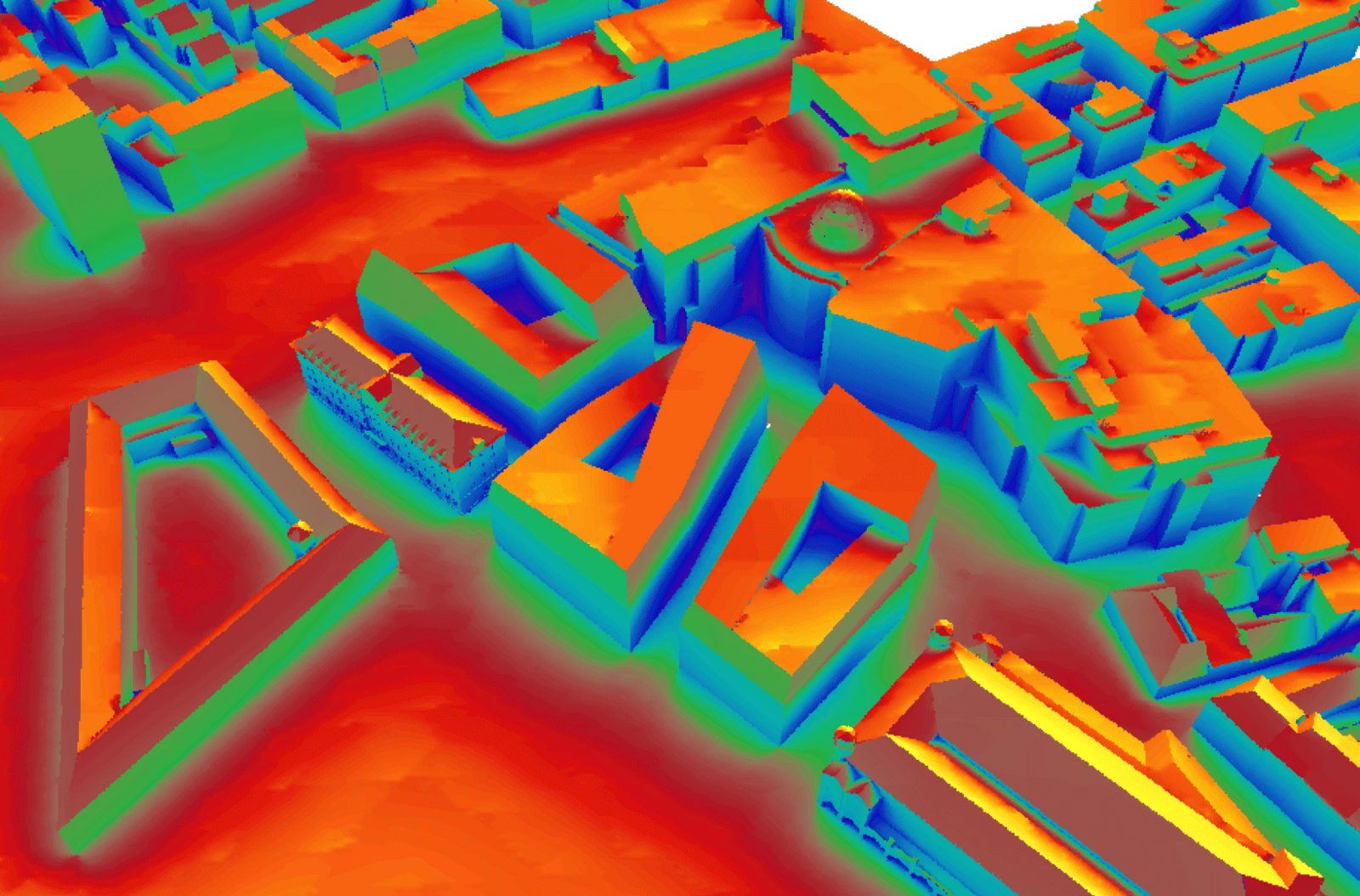

KTT When we ask ourselves what it would mean for a building to not use any energy, we look only at the building itself; the embodied energy in its materials and its systems like heating and cooling, ventilation, and daylight. That gives us a figure that we need to offset through energy production. But we don’t include the computational and sensor systems required to achieve that, or white goods like refrigerators, in those calculations.

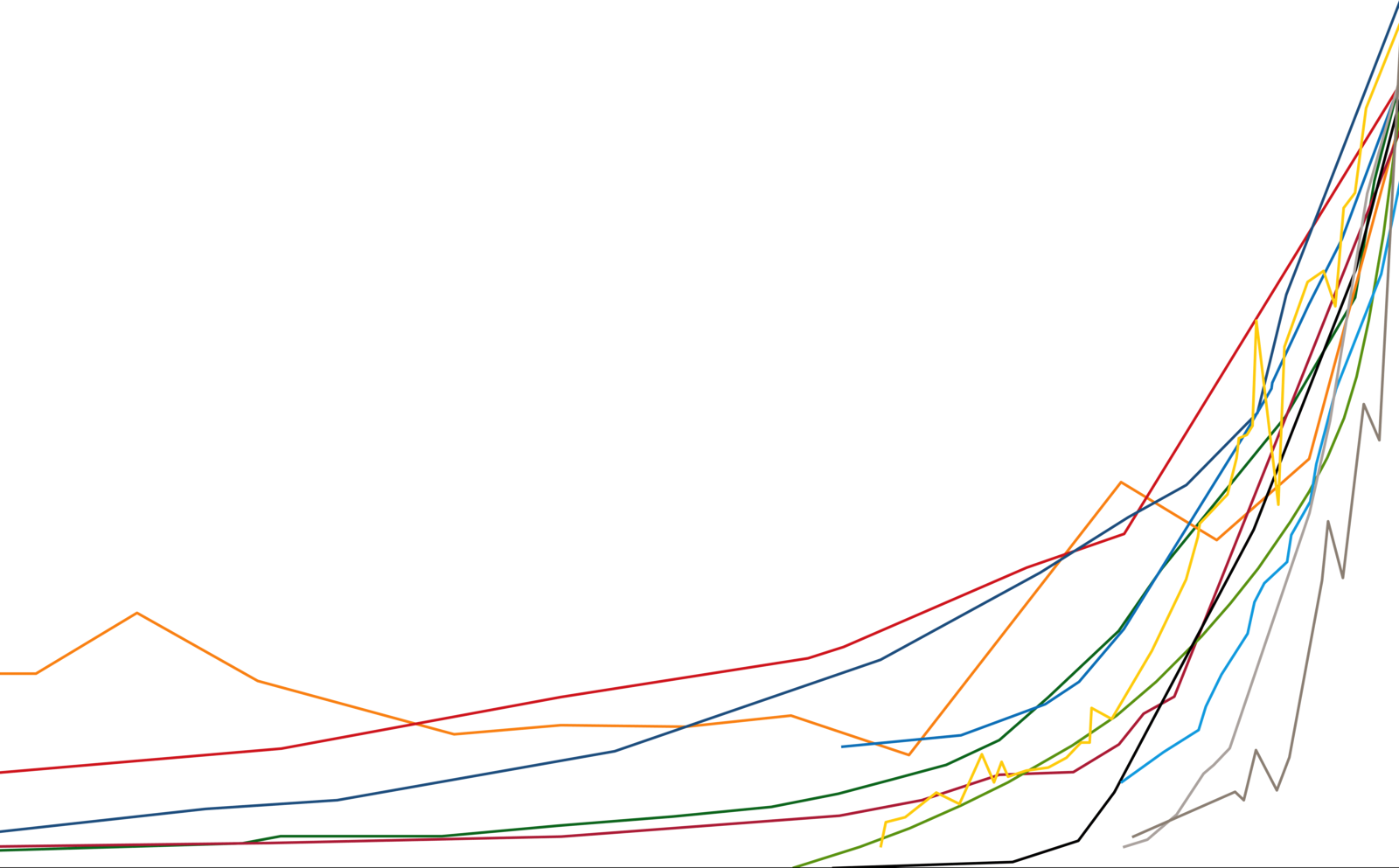

NA Zero is a status that’s only reached for a split second; with ongoing energy production, at a certain moment, the building will flip from energy negative to energy positive. I imagine that if clients are commissioning a zero energy building, they want to know how long it will take to get there.

KTT Yes, and it’s relatively straightforward to figure that out. All we need to do is calculate the building’s CO₂ equivalent of everything is, which means determining the embodied energy in everything, even down to the stainless steel screws coming from wherever it’s coming from and what kind of energy is used to produce it. We could go all the way down to the food the construction workers eat and the clothing they wear, or the personal consumption of the architects designing the building, but we’re currently leaving that out. Once we have a complete picture of the building’s CO₂ equivalent, including the recycling of the building at the end of its life cycle, maintenance, operational electricity, and so on, we balance it with how much on-site clean energy can be produced. In our Brattørkaia powerhouse project, for instance, we’ll reach zero in sixty years. But that means, starting from day one, we have to produce an average of 50% more energy than the building actively consumes.

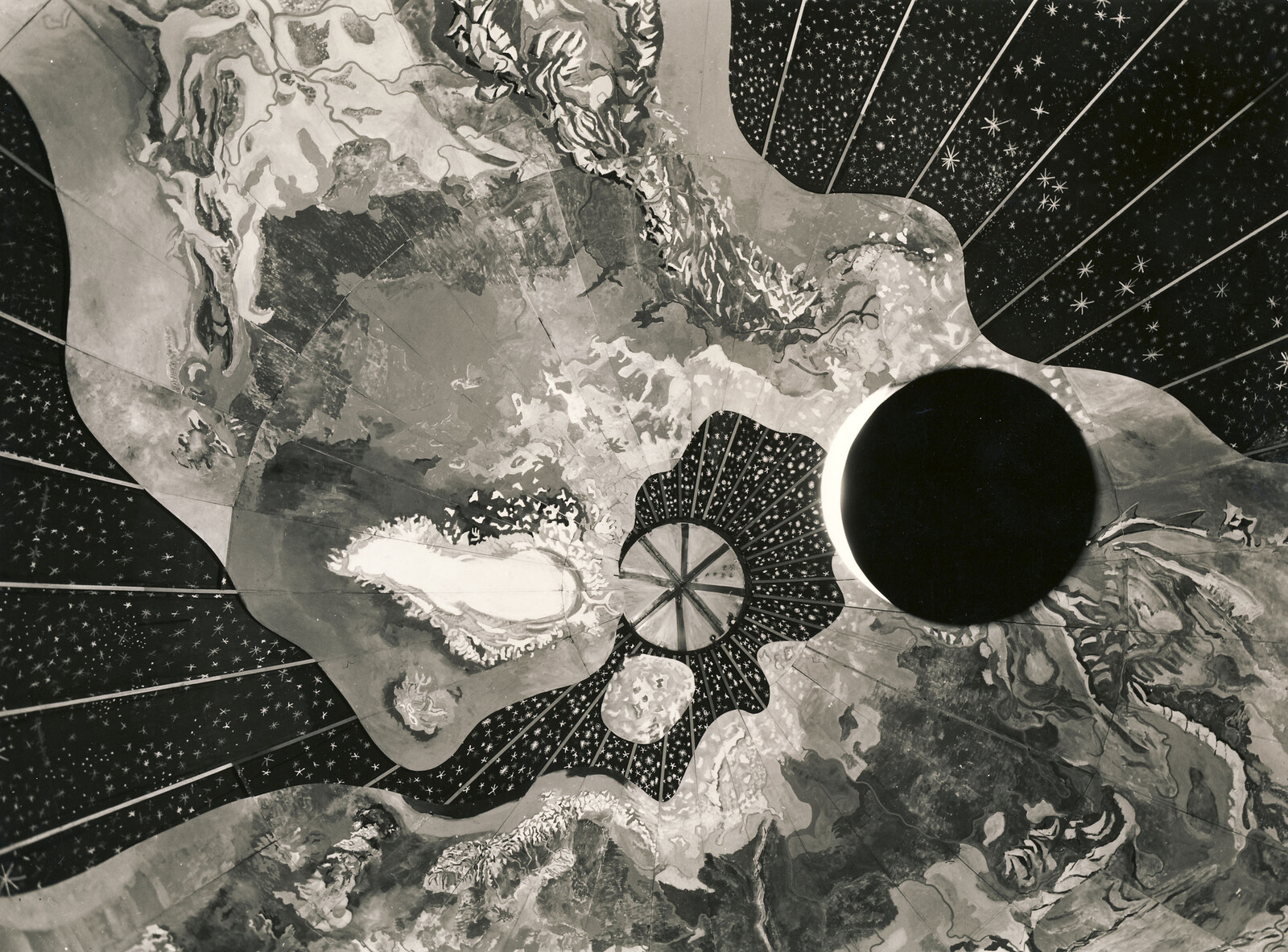

Snøhetta, Harvard HouseZero, 2016-2018, Cambridge. Photo: Michael Grimm. © Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities.

Snøhetta, Harvard HouseZero, 2016-2018, Cambridge. Photo: Michael Grimm. © Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities.

Snøhetta, Harvard HouseZero, 2016-2018, Cambridge. Photo: Michael Grimm. © Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities.

Snøhetta, Harvard HouseZero, 2016-2018, Cambridge, sustainability diagram. © Snøhetta.

Snøhetta, Harvard HouseZero, 2016-2018, Cambridge. Photo: Michael Grimm. © Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities.

NA Is a similar strategy employed in the HouseZero project?

KTT No. We’re trying to have HouzeZero be CO₂ negative from day one. The embodied energy of existing structures isn’t factored into CO₂ calculations.

NA How can you write off the embodied energy of the existing?

KTT Well, you can, when it comes to the project itself and whatever you are contributing in terms of new CO₂, but you cannot when it comes to questions of justice and the global distribution of CO₂.

NA What does it take to build a building, or make an intervention into one, that is CO₂ negative from day one?

KTT What’s most important is to find and use materials that have as little embodied energy as possible. But you cannot look to the normal construction industry for these.

NA Why not? And if not, where can you find them?

KTT The building industry of today was developed according to a previous generation’s set of standards, one that was not concerned with issues such as low embodied energy. And alongside that, a set of laws and regulations were created that protect the norms of the industry. There’s a very close relationship between what and how you’re allowed to build and what you’re allowed to build with. That’s why it was so great to do this project with Harvard. It’s a research environment, which allowed us to work with new materials and learn from different forms of knowledge.

NA There is so much already built, and there is increasing awareness that that we don’t necessarily need to build new; we can reuse the old. Is this a paradigm shift that your practice is adapting to?

KTT Yes, a lot of projects we’re doing are retrofits, both of buildings and urban areas. But these projects are often concentrated in the West. That is the issue with degrowth: it needs to be implemented in West, but it shouldn’t be addressed to people who live on a dollar a day. It’s unjust. You cannot talk to certain parts of the world about degrowth, where the discussion should be about sustainable growth. The biggest task is redistribution.

NA What, in your opinion, would it take to redistribute carbon at a global scale? Or, said differently, to reduce the West’s carbon output?

KTT The discussion in Norway, for instance, is how much money would you need to pay people.

NA Like gun buyback programs? Carbon buyback programs.

KTT Maybe it’s voluntary too. I think we need to not lose faith in the public. Our Oslo Opera House project convinced politicians that it’s possible that motivate people who don’t go to the opera to go to the opera. You can convince people through extreme generosity.

NA Generosity is so out of place within the paradigm of austerity that the Western world has largely been governed by since 2008.

KTT I’m not a climate pessimist, but I do assume that we’re no longer able to meet the two-degree goal. Everyone in the green industries is trying to move towards this goal, but what happens if we don’t reach it? We need a plan B.

NA It’s interesting, because one of the main catchphrases of the climate movement today is that “there is no planet B.” And there is no planet B, but I agree that we need a plan B. If anything is evident, it’s that plan A is not working. We’re trying to get our politicians to make these changes, we’re trying to go to the UN and to have them do something—that’s plan A, that’s how over the course of the twentieth century we’ve been told: “This is the way politics works, this is the way the world can be changed.” But it’s not working.

KTT We really don’t know what will happen if it doesn’t work. But we need to be ready for that. It’s like saying that a building should finish by October 20, 2021, and everyone is working towards that goal, but what if it doesn’t happen? If it’s not finished, what are we going to do? It certainly doesn’t mean everything that was built is useless. We need to learn to see and use what we have in a new way.

Overgrowth is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Oslo Architecture Triennale within the context of its 2019 edition, and is supported by the Nordic Culture Fond and the Nordic Culture Point.

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)