Everybody knows that our cities

Were built to be destroyed

—Caetano Veloso

As the architecture profession continues to struggle in a contemporary landscape where economic and technological forces erode its agency, every Venice Biennale begins by answering a single question before making any other statement: What is architecture? This obstruction makes it difficult to find the common ground necessary to make a cohesive large-scale exhibition like the International Architecture Exhibition. If we can’t agree on what architecture is, how can we agree on what “freespace,” the title of its 2018 edition, is? The curatorial team of Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Dublin-based Grafton Architects sidestepped this problem by conceptually tackling the architect’s horcrux: space. The architects explain their idea of space as an immanent concept of the here and now, even identifying it with nature.

The curators’ point of view on the role of architecture vis-à-vis “each citizen of this fragile planet” is one of responsibility and generosity, which they have brilliantly demonstrated in their built work. But under the guise of the “freespace,” the curators’ “manifesto,” which is constantly referred to but never once present in the exhibition itself, poses a bigger question as to the nature of contemporary space. The idea that space manifests only when there is architecture runs throughout the curators’ statements that frame each of the projects on display. While perhaps this was once true, today, space is morphed by the development of increasingly sophisticated processes of abstraction and computation. In this scenario, a purely phenomenological, formal, material, or tectonic understanding of architecture is a lost cause. Instead, the architects’ struggle for agency should focus on these new forms of abstraction and computation of the real, incorporating them into the realm of what can be designed.

Space is defined as an abstract construct not within, but next to the Biennale, in Armin Linke’s exhibition “Prospecting Ocean,” located at the Institute for Marine Science. In an interview about the history of science and the project of measuring the depth of oceans and the height of mountains, Franco Farinelli, president of the Italian Association of Geographers, quotes an ancient poem by the philosopher Ferecide, one of the Seven Sages of Greece, in which the ur-marriage between the Earth and the Sky is officiated by the Ocean. During the ceremony, the Earth receives a cloak embroidered with rivers, mountains, lakes, and architectures. It is only then that the Earth transforms from pure abyss into intelligible, measurable, and inhabitable space.

Like an unfortunate many of the Biennales in recent years, this edition seems to resolve itself merely to circumscribing what the curators like. Yet unlike David Chipperfield’s Common Ground from 2012 or Alejandro Aravena’s Reporting from the Front of 2016, Freespace eschews a political fig leaf for honesty and simplicity in their display of taste. As Chipperfield, Aravena, and Farrell and McNamara demonstrate, it is curious how the Architecture Biennale often serves as its curators’ first experience in curating an exhibition, let alone one of this scale. If the architects chosen to direct the Biennale have no previous curatorial, not to mention theoretical experience, should we expect these exhibitions to be anything more than mere displays of taste? Perhaps not. And while taste is a perfectly valid criteria if considered as a lifelong practice of feedback, a Biennale based on its premise conflicts with the idea that the exhibition should have a role in both reflecting and shaping architecture’s collective, if not universal discourse.

What resulted in this edition is a sort of real estate subdivision program, not unlike a trade or art fair in which the curators make a wish-list of participants who are given a plot of land and left alone to do something within. The Corderie dell’Arsenale was comprised of a disappointing sequence of advertorials of recent work from architecture practices that were not nearly dissimilar enough from what one might find in their Instagram profiles or websites to justify putting down one’s phone, let alone a trip to Venice. As with Alison Brooks’ wooden “totems” that claimed to speak of housing’s civic role by way of forced perspective and optical illusion, or Benedetta Tagliabue’s fiber canopy that stretched the metaphor of “weaving” well beyond any textile limit, contributions tended materialize in the form of full-scale structures. Yet in failing to engage the body with phenomenological dimensions of light, color, and geometry, or the mind with the tectonic materiality of gravity, the work remained largely inconsequential, somewhere between but neither exhibition design nor architecture, and the space, even during the opening, dead.

Curatorial ambitions were slightly raised in the Central Pavilion, where not all propositions displayed were just representations of recent work. In the first room, Assemble showed a pretty tiled floor from their ongoing Granby Workshop project which emphasized the role of accident in craft while furnishing arguments against the welfare state by glorifying Big Society’s “integration of the free market with a theory of social solidarity based on hierarchy and voluntarism.” Just beyond, above in the balcony were the beautiful models of Peter Zumthor. Made using his signature palette of materials—wax, concrete, cardboard, chalk and dried plants—the models represent various contexts, from a forest in Norway to downtown Los Angeles, as if they are part of the project itself (or vice versa). The architect explains his method of working on models as a sculptor, with an endless form-finding exercise framed by the material conditions of the model itself and the limited simulations of reality it allows.

Elsewhere, the exhibition invoked the use of history and canonical buildings to very different ends. The central space of the Central Pavilion contained a seemingly arbitrary display of models representing what the curators themselves consider to be significant buildings of the twentieth century. Cino Zucchi used the work of Luigi Caccia Dominioni, who defined the haute bourgeoisie canon of the Milanese apartment building, to support his own, arguably less successful explorations of this typology. In a similar fashion, David Chipperfield cemented his role as the Architect-in-Chief of Angela Merkel’s nouveau Prussian classicism by presenting an enlarged, almost life-sized perspective drawing by Friedrich Schinkel as the inspiration for his newest project on the Museum Island in Berlin. Nearby, Petra Gipp and Mikael Olsson’s rigorous assembly and direct display of three canopies designed by Sigurd Lewerentz for religious buildings, curated by Kieran Long, Johan Örn, and James Taylor-Foster, stands out as a model for the contemporary exhibition of historical architecture in its careful selection of a wide range of material as well as its subtle deployment of abstraction in its modes of representation.

This biennale once again revealed a profound disconnect between practicing architects that inherit models of interpretation of the real from older generations and younger architectural practitioners who, confronted with new and rapidly evolving technological paradigms, are exploring new ways of using and producing architectural discourse. Outside of the main exhibition, and even beyond the official program of the Biennale itself, a number of National Pavilions and independent exhibitions signal these efforts.

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Vatican Chapel, San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, 2018. Photo: Laurian Ghinitoiu.

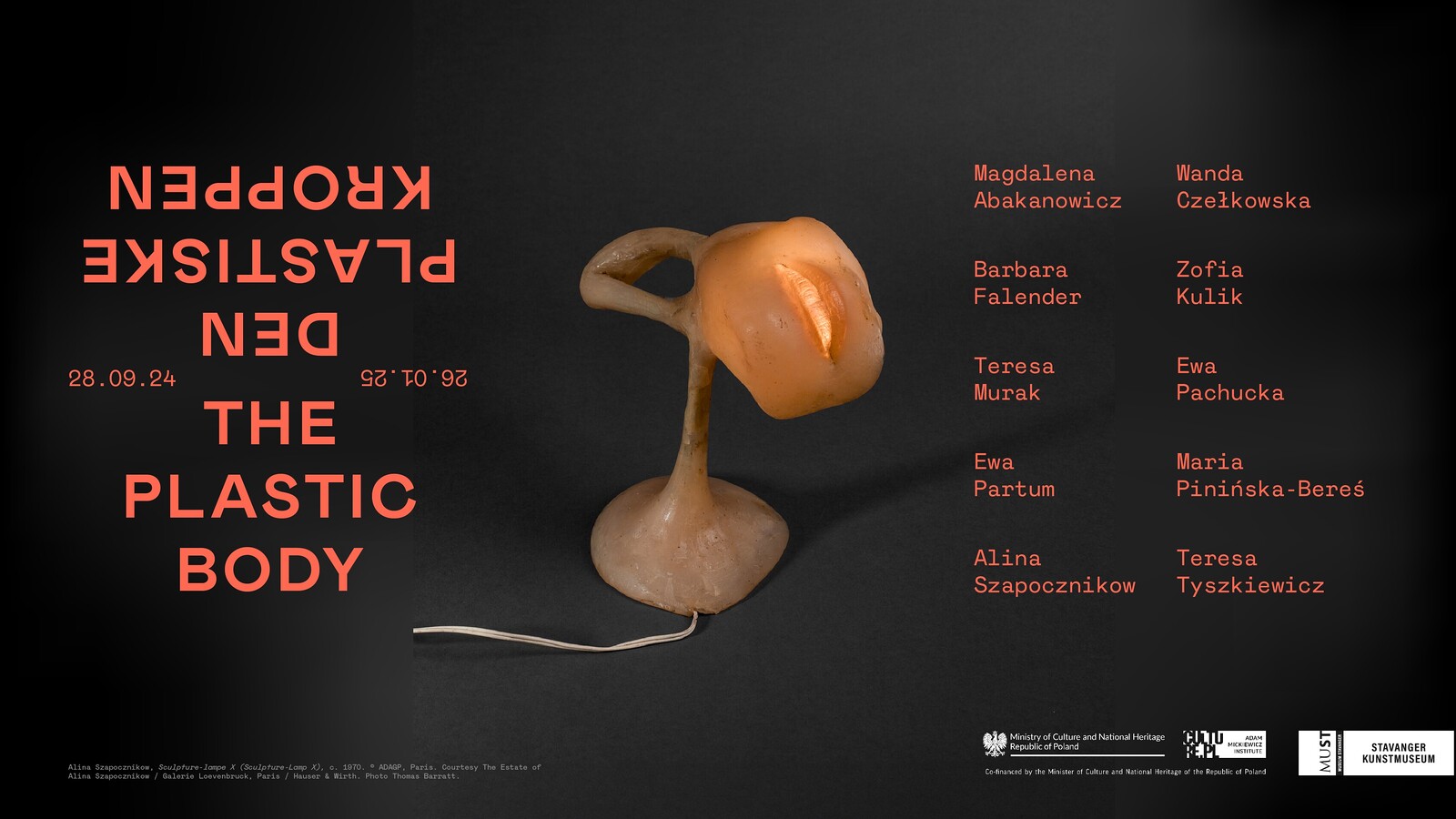

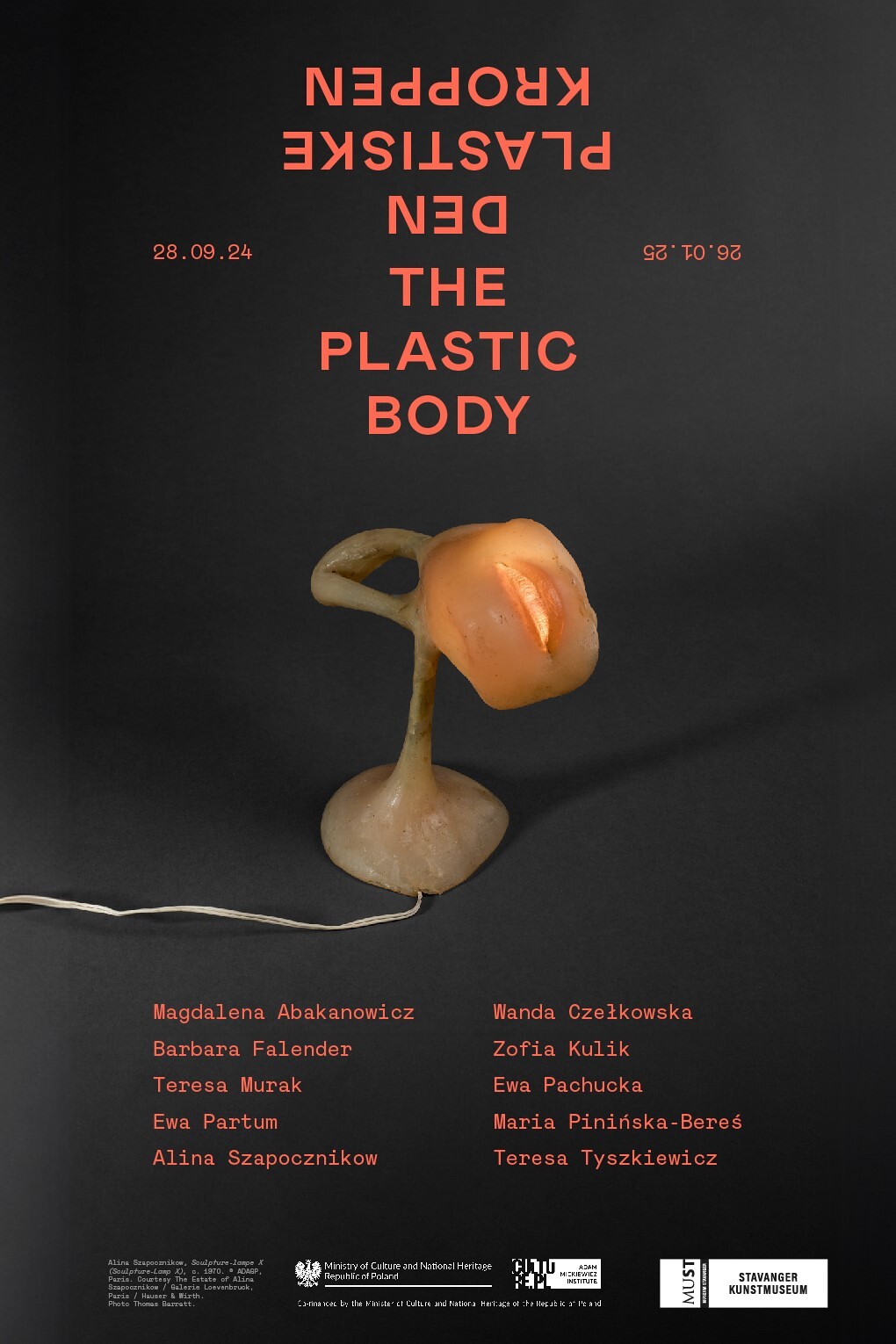

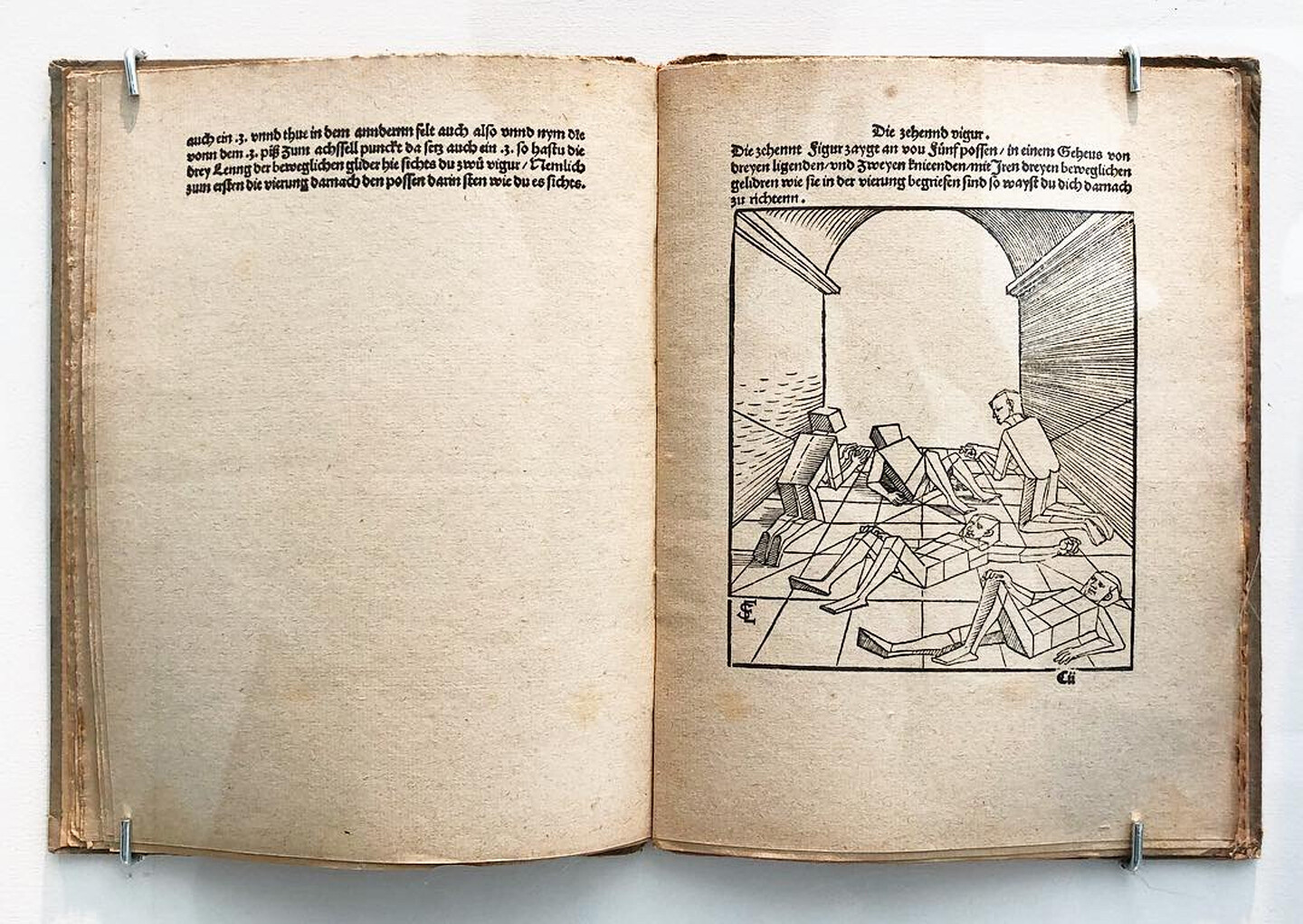

Detail of Erhard Schön, Unnderweissung der proportzion unnd stellung der possen, 1540, in Simone C. Niquille, Safety Measures, Rietveld Pavilion, Venice, 2018. Photo: Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli.

Alisa Andrašek and Bruno Juričić, Cloud Drawing, Arsenale, Venice, 2018. Photo: Luke Hayes.

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Vatican Chapel, San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, 2018. Photo: Laurian Ghinitoiu.

In the Dutch pavilion, for instance, Liam Young presents his research into the geopolitics of CGI, while Simone C. Niquille’s inflatable rendition of a sixteenth century engraving by Erhard Schön highlights the pre-digital, alchemic intuition that the human brain relies on abstract representations of reality, and points to the way that contemporary protocols of standardization and automation are informed by racial and body bias. Back in the Arsenale, the Croatian pavilion also focused on the aesthetics and spatial consequences of emerging paradigms of augmented intelligence by presenting a full-scale pergola designed by Alisa Andrašek and Bruno Juričić made using robotic fabrication and automated design protocols. The Cruising pavilion presented an exhibition glamorizing the gay male experience of re-appropriating space under conditions of oppression and marginalization, and the Holy See participated for the first time with an exhibition curated by Francesco Dal Co of eleven devotional chapels built in the gardens behind Palladio’s San Giorgio Maggiore, which revealed not just the urgency, but also the ability for architecture to speak about the human condition and its limits.

Particularly in light of these, and other noble curatorial attempts elsewhere, it seemed throughout the main exhibition that architects are simply ignorant, if not dismissive of the practice of making exhibitions. Contemporary exhibitions of architecture, as this edition of the Biennale demonstrates, tend to oscillate between two poles: as either displays of architecture through the established language of the architectural project and reliant on its operative techniques of abstraction (i.e. drawings, models, or fragments), or displays of works or artifacts about architecture, space, building, or any concept that can otherwise be defined as “architectural.” This Biennale’s International Architecture Exhibition seems to be lost somewhere between the two: most architects improvised as installation artists, forcing their conceptual frameworks into three dimensional constructs that tend to be anesthetic and mute, with their project encompassed entirely within wall text.

An exhibition is a complex organism reliant on its own specialized discourse which spatializes ideas and where the sum of the artifacts exhibited results in an excess of knowledge produced. In a moment when architecture’s agency continues to be undermined by a myriad of forces, architects should harness the tremendous possibility of producing architectural knowledge with and through the exhibition format. This edition of the International Architecture Exhibition was disappointing and will continue to be until more focus is placed on the emerging technical paradigms that are profoundly reshaping the way this planet is inhabited. It is only by doing so that architects and non-architects alike might be able to understand, create, and work to belong to contemporary space. Perhaps one way to start would be to give the exhibition’s curatorial duties to a curator.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)