Nick Axel How do you see your role as an architect today?

Sou Fujimoto My role as an architect is to create space for people, space that does not control but that allows for different things to happen. Space that inspires people to behave as they like, or beyond. Architecture belongs to society, no matter how small or large. So architects have a responsibility to give shape or form to society, which will hopefully make society better and people happier.

Nikolaus Hirsch Looking at the evolution of your work, it’s obvious that the scale has changed from small projects, like the early House NA project from 2012, to more recent, large-scale projects, like Village Vertical in Paris. To what extent has your approach to space making changed due to this increase in scale?

SF In my early days, the scale I worked at was quite small. In a private house, for instance, you sit here, and other people sit there, to make conversation. Those kind of physical relationships are quite important, and we can design for them. This is still the foundation of my architectural design. So even in larger scale projects, I try to maintain an intimate feeling and understanding of space. At the same time, if the architecture is bigger and occupies a larger place in society, like a fifty-meter high tower, or a 10,000, even 50,000 square meter project, different meanings can happen. It is not that these larger scales replace the smaller scales, but rather add new layers of architectural thinking.

Sou Fujimoto Architects, House NA, Tokyo, 2012. Photo: Iwan Baan.

NH How would you describe the relationship between the architectural and the social?

SF Even a small private house is social. It has a physical presence on the site, so people can potentially see it. But it’s not just about these physical properties. The concept of a new lifestyle, or the possibility of living differently, is a public thing. Even if that client is the only one who will live in that house, changing the way one thinks or lives, the meaning of its functions, or of buildings themselves, is an important public role for architectural design. Even smaller things have larger influences. When I was working at smaller scales, thinking about private, intimate conversations, I always knew that they could have a wider influence on the world, on history, on society. So I was, in a sense, always working at larger scales. But now, in making architecture for a larger public, sometimes it should just be an object, a landmark, a representation of not just the past and present, but also the representation of the possible, of the hope for things to come. This is why I am thinking more and more about the idea of integration: listening to the site, to the complex situation of the area or society, its cultural background, climatic conditions, the client’s desires, etc. I like to listen carefully and then try to find harmony or balance between diverse forces in these complex situations.

Sou Fujimoto Architects, Mirrored Gardens, Guangzhou, 2011–2014. Image courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space.

NH One of your clients is Hu Fang from Vitamin Creative Space for whom you designed Mirrored Gardens, an exhibition complex in the countryside near Guangzhou, China. How would you describe the approach you took when working on that project?

SF That project was actually the first time I listened carefully and didn’t try to push my own ideas. The more I was there and talked with Hu Fang, walked around the village and talked about his ideas of harmony between gardens, nature, buildings, art, and people’s activities, the more I became anonymous or transparent. I used to be more egocentric, trying to make something interesting. But in this project I just tried to listen. The buildings that I ended up designing are a combination of abstract, figural houses with local materials. They were the result of my conversations with Hu Fang. The client is living there, so they’re constantly changing too; continually integrating art, agriculture, and nature. It is an endless process.

NA I’d like to return to your smaller projects, because there’s something incredibility striking and very radical to some of your earliest houses, like the Wooden House or House NA. I want to speak about these relations between people that you say architecture can shape. These projects fall largely within a modern tradition of Japanese architecture where you work with singular architectural elements throughout a space, but you bring them into close proximity with the human body. So when you say that a house could only be for one specific person, I can’t help be reminded of the work by Absalon, where he would have to train himself how to live in the houses he designed for himself; how to get in and out of bed, how to open the cabinet so as to not hit his head, etc.

SF When I designed those projects I was trying to create a new concept of space. I tried to make something different from the architecture of the day. At the same time, it was never about making crazy shapes or anything. I always anchored my designs to the fundamentals of architecture, which at that time, I thought must be human behavior, or the human body. The relationship between the human body and space was the beginning, but the module was key. I tried to redefine architectural space by using non-architectural modules. Modern architects said that architecture should be functional, but in fact they needed furniture to make it functional. Modern architects just provided open space. I was trying to retrace those thought processes to find something new. So I used furniture-like modules to integrate architecture and furniture. The Wooden House was universal, in a sense, because there was no specific client, no specific lifestyle. We just thought about how the behaviors of people could be laid out in three-dimensions; lying down, sitting, climbing, etc. Overlaying many different behaviors on top of one another in one place was an exercise for me to help understand the relationship between three-dimensional space and the human body.

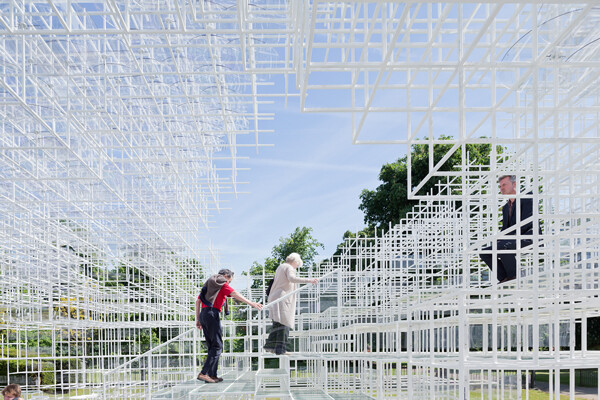

Sou Fujimoto Architects, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, London, 2013. Photo: Iwan Baan.

NA What happened to that line of investigation?

SF During that process, I found that there was a really strong contradiction. I was trying to make a space without intention, which would allow people to find their own way to use it, but when I make a model or a study, it’s already a projection of my intention. I was intentionally trying to make a place without intention. This was already over ten years ago, so I was thinking that maybe some computer program could make the decisions, so then there would finally be a non-intentional space. But even still, the contradiction remained. In my Serpentine Pavilion in 2013, I faced the same problem, but also faced another contradiction, of scale. The Serpentine Pavilion was bigger than the Wooden House, about twenty-two by twenty-five meters. It was also a public space, so I had to create different areas. Unity was still important, but the repetition of a forty-centimeter module over the entire volume threatened the diversity of the space. If you repeat something 1,000 times, it becomes quite homogeneous.

Sou Fujimoto Architects, Nicolas Laisné Associés, and Manal Rachdi Oxo architects, L’Arbre Blanc, Montpellier, 2014–current. Rendering: RSI-Studio.

NA What sorts of lessons have you taken from this idea of a non-intentional space, or in the case of the Wooden House, maybe a non-specific subject? You are now designing residential towers, where you have no idea who will live there. But I imagine you still want to be able to contribute something. As you said at the very beginning, maybe even change the way people live.

SF The Serpentine Pavilion made me realize that this method is not universal. It also made me realize that it’s the relationship between scales that are most important: not just repeating the same modules endlessly, but creating scalelessness. If you think about the size of the finger compared to the size of the hand, the arm, and then the body, it is a harmony amongst different parts and different scales that is most important in making something functional. This is, in a sense, the classical meaning of proportions. It’s funny to go around to all sorts of strange places just to come back to some really simple principle. The housing project we are now planning in Montpellier, for example, it has 105 units, and is fifty meters tall. We cannot make everything by forty-centimeter modules, but we cannot, of course, ignore those small scales.

NA How do you create relationships among these different scales? As the architect, are you even able to work at all of them?

SF The question is how to harmonize a piece of architecture, not just as a big object in the landscape, but also in the experience of domestic and daily life. I’m increasingly concerned about integration, from the relation a building has to its surroundings, to architectural details just a few millimeter thick. But when working at larger scales, sometimes we have to ignore some things. The interiors of the Montpelier housing project, for example, are not controlled by us. The units are meant to be sold and for the owners to fit out themselves. Some scales are black boxes, and some are more malleable. When working at small scales, there are almost no black boxes. But of course, I never treat these black boxes as givens. I always try to expand the scope of what we can design. Sometimes there is pushback from the client, or from many other things, but pushback is not just pushback; it’s something we can understand in different directions. The reinvention, or reappraisal of every given situation is where architecture begins.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

Positions is an initiative of e-flux Architecture. This interview took place during the e-flux conversation series Practice at Milano Arch Week 2018, held at the e-flux Teatrino pavilion designed by Matteo Ghidoni—Salottobuono, made with the help of the Friuli-Venezia-Giulia (FVG) Region and by Filiera del Legno FVG (with the coordination of Regione FVG and Innova FVG).

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)