June 30, 2025

The National Museum of Contemporary Art of Romania recently opened the exhibition Kazimir Malevich: Outliving History. The show includes three previously unseen canvases attributed to Kazimir Malevich, alongside a selection of fourteen abstract works by contemporary Romanian artists.

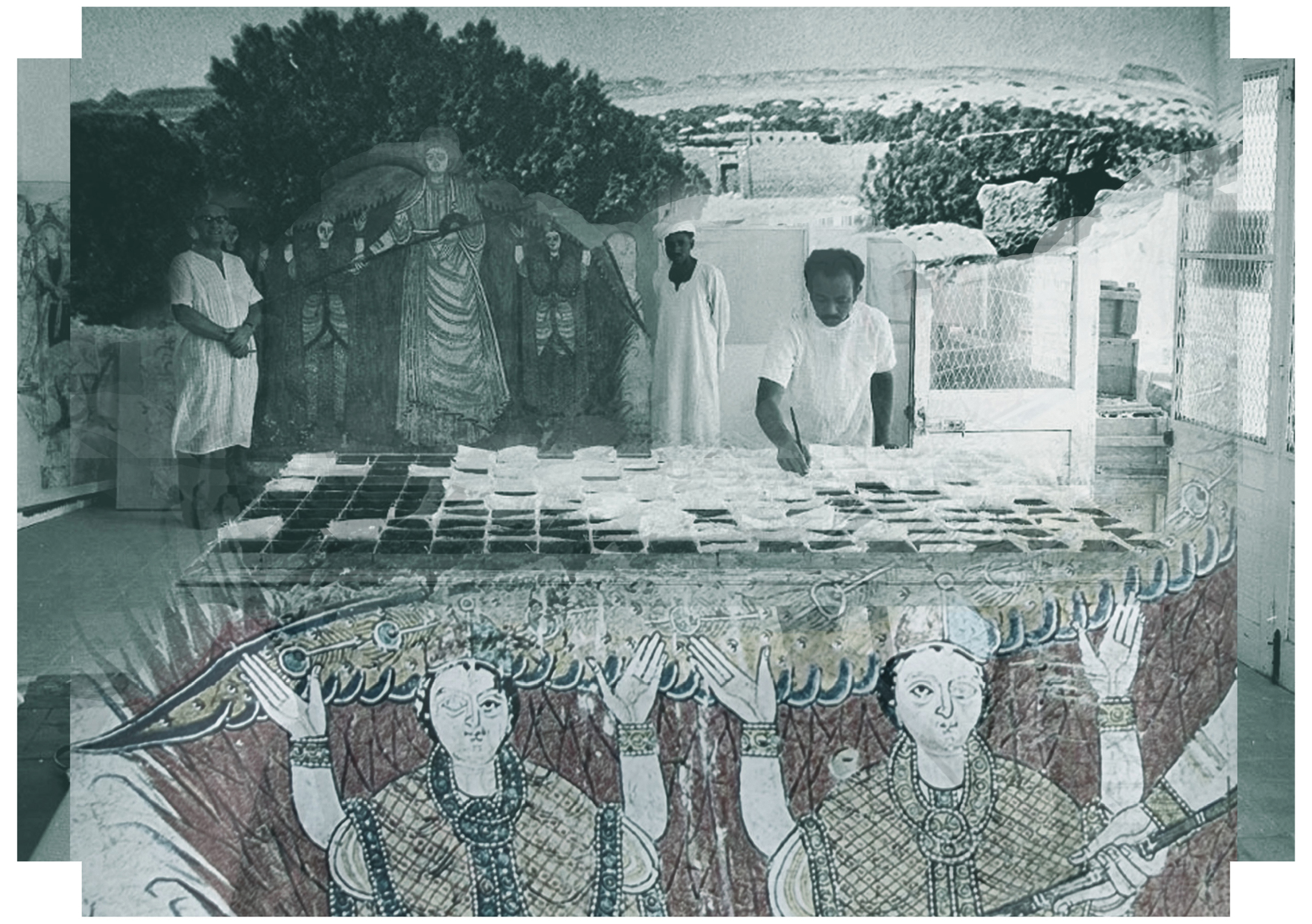

By Konstantin Akinsha

June 3, 2025

As Alumni, Faculty, and Friends of the Whitney Independent Study Program, we unequivocally support the 2024–25 ISP cohort who were censored when presenting work in solidarity with the struggle for Palestinian freedom. We uplift their efforts to create and debate art while reckoning with political violence and institutional coercion, and affirm our shared solidarity against the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

Issue #155

June 23, 2025

Issue #154

May 12, 2025

Issue #153

April 7, 2025

Issue #152

March 4, 2025

Issue #151

February 4, 2025

Issue #150

December 16, 2024

Issue #149

November 5, 2024

Issue #148

October 8, 2024

Issue #147

September 9, 2024

e-flux

Harvard University Graduate School of Design

MASS awarded 15th Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban DesignGeorge Kuchar

July 2025

July 11, 2025

Matters of Activity, Cluster of Excellence at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Michaela Büsse

Blazing Heath/Heideglühen

Blazing Heath/Heideglühen

July 10, 2025

Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College

Class of 2026

Double Take

Double Take

July 9, 2025

Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design

Rundgang 2025

July 8, 2025

Academy of Fine Arts in Prague

Lecturer in the Art in Context programme

July 7, 2025

Maumaus Independent Study Programme

Call for applications 2026

July 4, 2025

University of Westminster, London

Undergraduate and postgraduate Arts and Technology courses

July 3, 2025

Bennington College

Of Things Not Seen: The Body as Witness and Participant

July 3, 2025

Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts in Qatar

VCUarts Qatar at London Design Biennale

Matter Diplopia

Matter Diplopia

The Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College

University of New Mexico